Change in the Uses of Urban Public Spaces by Cairo People (With a Special Focus on Public Gardens)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

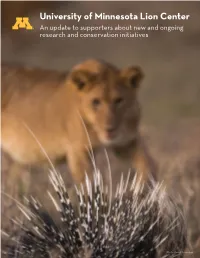

Oxytocin to the Rescue? a New Approach Being Tested by Jessica Burkhart Could Relieve Social Stress for Captive Lions and Aid in Future Conservation

University of Minnesota Lion Center An update to supporters about new and ongoing research and conservation initiatives Photo: Daniel Rosengren DIRECTOR’S NOTE A most unusual year Research moved forward at a slower pace, but there were bright spots in our work to inform wildlife management practices. he COVID-19 pandemic has been challenging for impact on wildlife movements — instead protecting people us all, as we each faced extended periods of iso- from dangerous animals and, in turn, protecting lions and Tlation and many of our friends and families were elephants from retaliatory killings. Though largely a measure personally touched by tragedy. Vaccines remain scarce in of last resort, we know from our earlier work that lions thrive Africa, and waves of infection are still crashing in many when they are separated from local people by a strong of the countries where the Lion Center works. The Delta fence — and as Africa’s human population is still growing variant adds more uncertainty. fast, the human-dominated areas will expand ever closer to the remaining lion strongholds. As seen in the following pages, we all managed to carry on even though the pandemic seriously curtailed our field Earlier this summer I also finished my new book, tentatively research in 2020. Jessica Burkhart (p. 4), Abby Guthmann titled The Lion: Behavior, ecology and conservation of an (p. 6) and John Heydinger (p. 2) returned to South Africa, iconic species. Unlike Into Africa and Lions in the Balance, Kenya and Namibia, respectively. Sarah Huebner’s (p. 3) in -

955 Nohope Diceros Bicornis

species L. carinatus is distinguished from all the The bright brick-red throat, quite Merent other species of this genus, includmg even from that of the adults, was particularly re- L. cubet~siswhich is more common in Cuba, by markable. The yellow-brown tail, whch be- a particularly strong development of a com- came caudally lighter, bore more clearly than ponent of aposematic behaviour: its tail has a do those of adults the strongly defined dark definite threat function and is then rolled up cross markmgs (a phenomenon frequent in dorsally in a ring or a spiral and is carried over juvenile lizards, probably of an aposematic the back. (L.personatus also shows th~sbe- nature). The young animal was reared in haviour in a somewhat weaker form, though isolation in a separate container. The ‘rolling’ here the tad is moved more sinuously. of the tail was seen for the first time on the (Mertens, R., 1946: Die Warn- und Druh- second day of life, which, as was to be ex- Reaktionen der Reptilien. Abh. senckenberg. pected, demonstrated that this was an in- naturfi Ges. 471). herent instinctive action. When the young The hatchmg of a Roll-tailed iguana (we animal sat at rest, clmging to a sloping branch, call it hson account of its characteristic its tail lay flat, with at most the extreme end of threat behaviour) in the East Berlin Zoo must it turned upwards. However, as soon as it went be the first to be recorded in Europe. The into motion the tail with its remarkable stria- adult animals arrived on the 9th August 1962 tion was jerhly raised and rolled up high over after a tenday journey by cea. -

Cop15 Doc. 24 CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL TRADE

CoP15 Doc. 24 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Doha (Qatar), 13-25 March 2010 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Compliance and enforcement ENFORCEMENT MATTERS 1. This document has been prepared by the Secretariat. 2. As required in Resolution Conf. 11.3 (Rev. CoP14) (Compliance and enforcement), the Standing Committee reviewed this subject at its 57th and 58th meetings (Geneva, July 2008 and July 2009) (see documents SC57 Doc. 20 and SC58 Doc. 23). Egypt 3. The Standing Committee, at its 57th and 58th meetings, considered reports from the Secretariat in relation to Egypt’s implementation of recommendations that had been made after a mission to the country in November 2007. The report of the mission had been presented to the Committee in document SC57 Doc. 20 Annex. At its 58th meeting, the Committee expressed concern regarding the time being taken to fully implement the recommendations and it requested Egypt to submit a report on this matter for consideration by the Conference of the Parties at the present meeting. 4. The Committee’s decision was communicated to Egypt by the Secretariat, which also suggested that a mission to Egypt to assess and verify implementation prior to CoP15 might be appropriate. Egypt has undertaken to submit such a report and has indicated its willingness to receive a mission by the Secretariat. Egypt’s report will be annexed to this document in due course and the Secretariat will report further orally at CoP15 on this issue. -

CITES SECRETARIAT Enforcement-Needs Assessment

SC57 Doc. 20 Annex / Anexo / Annexe (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CITES SECRETARIAT Enforcement-needs assessment mission EGYPT 17–23 November 2007 SC57 Doc. 20 Annex / Anexo / Annexe – p. 1 Table of contents Table of contents.......................................................................................................................2 Background to the mission ..........................................................................................................2 Conduct of the mission...............................................................................................................3 Introductory remarks ..................................................................................................................3 General implementation and enforcement issues ............................................................................4 Illicit trade in ivory .....................................................................................................................5 Illicit trade in primates ................................................................................................................6 Rescue centres ..........................................................................................................................7 General observations – rescue centres..........................................................................................8 General observations – implementation and enforcement................................................................9 -

The Cairo Connection Part Ii

THE CAIRO CONNECTION PART II – APE TRAFFICKING – Enforcement missions by CITES Part of the solution or part of the problem? Karl Ammann & Pax Animalis August 2011 In 2001 the CITES Secretariat got for the first time involved in the ape trafficking issue in and out of Egypt when a deplorable case came to light. The Secretary-General took the unusual step to respond with two press releases (below). Today 10 years later we would like to evaluate what progress has been made in the context of Egypt and CITES compliance and enforcement. This is what this report is all about. Statement on the Cairo seizure of primates1 The Convention is an agreement between nations on how to regulate trade in certain wild animals and plants in ways that do not threaten the survival of these species. These ways involve common procedures and safeguards, and these are supported by advice and instruc- tions from the member countries (known as CITES Parties). CITES Parties can, and do, develop the many measures, provisions, instructions and advice that are needed to ensure that trade in wild species listed in CITES Appendices occurs in a manner that will not result in harm to live animals, in cases where trade is allowed. The provisions and procedures of CITES do protect thousands of live animals from cruel and inhumane treatment during transport every day. For instance, the Convention requires that any live specimens in trade be prepared and shipped so as to minimize the risk of injury, damage to health or cruel treatment. Detailed guidelines have been adopted for the humane transport of animal specimens, and the disposal of confiscated animals. -

(Family Columbidae) Occurring in the Gaza Strip – Palestine

30 Jordan Journal of Natural History 6, 2019 Notes on the Pigeons and Doves (Family Columbidae) Occurring in the Gaza Strip – Palestine Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou1* and Mohammed A. Abd Rabou2 Abstract: Birds are the commonest terrestrial area of about 27,000 km2, 540 avifaunal vertebrates among the fauna of the Gaza species are known to inhabit all types of Strip. Hundreds of bird species have been landscapes and ecosystems (Perlman and recorded and more records are being added Meyrav, 2009). The strategic geographic continually. Columbids (pigeon and doves), location of Palestine along with its major constitute a prominent component of birds, migration routes contributes to the diversity yet they have never been separately studied of bird fauna (UNEP, 2003). The arid to semi- in the Gaza Strip. The current study aims at arid Gaza Strip, which covers an area of about giving useful notes on the doves and pigeons 365 km2 (1.5% of the total area of Palestine), occurring in the Gaza Strip. Field visits, has a diversity of bird fauna occurring in its observations, photography, and discussions diverse ecosystems and habitats. Hundreds with stakeholders were carried out to reach of bird species have been recorded, and new the goals of the study. Seven species of more records are being added continually pigeons and doves were recorded in the Gaza (Project for the Conservation of Wetland and Strip. The Rock Pigeon Columba( livia) was Coastal Ecosystems in the Mediterranean found to be the commonest while the African Region – MedWetCoast, 2002; Abd Rabou, Collared Dove (Streptopelia roseogrisea) 2005; Yassin et al., 2006; Abd Rabou et al., was the rarest. -

WAZA News 3/11

August 3/11 2011 Lion Genetics | p 2 Sharks at Risk | p 7 Strategic Marketing | p 21 ) in Botswana. | © Cyril Requillart Cyril ) in Botswana. | © Panthera leo Panthera African lion ( WAZA news 3/11 Gerald Dick Contents Editorial African Lion Genetics ............... 2 Dear WAZA Members! Northern Rockhopper Penguins .............. 5 WAZA has embarked on a major mem- Sharks at Risk! ......................... 7 bership acquisition initiative with the French Association of Zoos .......8 support of Houston Zoo and Minnesota Romanian Zoos........................9 Zoological Garden, my sincere thanks © WAZA WAZA Interview: go to Rick Barongi and Lee Ehmke for Gerald Dick mimicking the condor’s flight. Shane Good ........................... 10 their support in realising the first image My Career: brochure for potential new members I also hope that you like the new Jeffrey McNeely ..................... 12 and people interested more generally feature stories in this edition, being the Book Reviews ........................ 15 in WAZA. The editorial burden was “WAZA interview” and “My Career” – Announcements .....................17 taken over by Carole Lecointre, our new which we hope to continue in future. WAZA Marketing Survey ........ 20 marketing staff member. Having this Another major marketing related activ- Marketing publication at hand (also available as ity took place in June, Granby, Canada. in Action: Granby ....................21 download from waza.org/get involved) The 7th Zoo and Aquarium Marketing Update it should be easier to answer questions Conference was a big success and International Studbooks ..........22 like “What is the benefit of becoming marks a milestone for future intensi- 200th WAZA-branded Project ....23 a member?” Please find a copy of this fied joint activities and cooperation. -

ZSL Trustees Report and Financial Statements

The Zoological Society of London Trustees’ Report and Financial Statements 31 December 2008 Registered Charity No. 208728 The Zoological Society of London Contents Page 1. Trustees’ Report 2 2. Independent Auditor’s Report 29 3. Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 31 4. Consolidated and Charity Balance Sheets 32 5. Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 33 6. Notes to the Financial statements 34 1 The Zoological Society of London Trustees’ Report The Trustees are pleased to submit this report and the financial statements for the year to 31 December 2008. Further information about the Society’s activities is given in a separate document, Zoological Society of London Annual Review (“Annual Review”) which can be obtained from the Finance Director or online from www.zsl.org. Objectives of the Society and Mission Statement The objectives of the Society as set out in its Charter are: ‘the advancement of zoology by, amongst other things, the conducting of scientific research, the promoting of conservation of biological diversity and the welfare of animals, the care for and breeding of endangered and other species, the fostering of public interest, the improvement and dissemination of zoological knowledge and participation in conservation worldwide.’ In addition the Society has adopted a Mission Statement, which reads: “To promote and achieve the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats” Public Benefit There are a number of ways in which the public benefit is pursued: • We run two outstanding collections which are open to the general public on 364 days of the year. The exhibits are designed to enable the public to experience the diversity and wonder of the animal kingdom by seeing a wide variety of species close up. -

DESIGN GUIDELINES for GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY

VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN: DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY (Under the direction of David Spooner) ABSTRACT Animal welfare organizations have developed criteria for zoo institutions with animal welfare as a top priority. This research aims to identify design guidelines for the Giza Zoo from the ‘visitor experience’ point of view, where the visitor experience is set as a base line to measure the effectiveness of zoo exhibits. The research identifies authenticity, aesthetics, recreation, education, and exploration as basic components of the visitor experience. These components are defined throughout the research, examined through case studies of the elephant and lion exhibits in three zoos, and are refined to further define visitor experience in the Giza Zoo. A redesign for the elephant and lion exhibits in the zoo is proposed based on these guidelines. INDEX WORDS: Zoological gardens, Giza Zoo, Animal welfare organizations, Zoo history, Visitor experience, Animal exhibits, Design guidelines. VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY B.S , Ain Shams University, Egypt, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Marwa Gewaily All Rights Reserved VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN: DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY Major Professor: David Spooner Committee: Marianne Cramer Pratt Cassity Josh Koons Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my major professor David Spooner for his support, guidance and patience, my reading committee for their interest and time: Marianne Cramer, Pratt Cassity, and Josh Koons. -

The Family Oestridae in Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Diptera, Oestroidea)

ZooKeys 947: 113–142 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.947.52317 CataLOGUE https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The family Oestridae in Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Diptera, Oestroidea) Magdi S. A. El-Hawagry1, Mahmoud S. Abdel-Dayem2, Hathal M. Al Dhafer2 1 Department of Entomology, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt 2 College of Food and Agricultural Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding author: Magdi S. A. El-Hawagry ([email protected]) Academic editor: Torsten Dikow | Received 22 March 2020 | Accepted 29 May 2020 | Published 8 July 2020 http://zoobank.org/8B4DBA4E-3E83-46D3-B587-EE6CA7378EAD Citation: El-Hawagry MSA, Abdel-Dayem MS, Al Dhafer HM (2020) The family Oestridae in Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Diptera, Oestroidea). ZooKeys 947: 113–142. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.947.52317 Abstract All known taxa of the family Oestridae (superfamily Oestroidea) in both Egypt and Saudi Arabia are sys- tematically catalogued herein. Three oestrid subfamilies have been recorded in Saudi Arabia and/or Egypt by six genera: Gasterophilus (Gasterophilinae), Hypoderma, Przhevalskiana (Hypodermatinae), Cephalopi- na, Oestrus, and Rhinoestrus (Oestrinae). Five Gasterophilus spp. have been recorded in Egypt, namely, G. haemorrhoidalis (Linnaeus), G. intestinalis (De Geer), G. nasalis (Linnaeus), G. nigricornis (Loew), and G. pecorum (Fabricius). Only two of these species have also been recorded in Saudi Arabia, namely: G. intestinalis (De Geer) and G. nasalis (Linnaeus). The subfamily Hypodermatinae is represented in the two countries by only four species in two genera, namely, H. bovis (Linnaeus) and H. desertorum Brauer (in Egypt only), and H. -

The Red-Billed Firefnch (LAGO N O STICTA SEN EGALA) in AVICULTURE – PART I I

The Red-billed Firefnch (LAGO N O STICTA SEN EGALA) IN AVICULTURE – PART I I Josef Lindholm, III Curator of Birds, Tulsa Zoo An unusually heavily-spotted Tulsa Zoo female Red-billed frefnch with its mate. At least four pairs have nested at the same time in Tulsa Zoo’s Desert Atrium. Nick Walters, photo. Meanwhile, in America… Tree are identifed as African. Tough all three are seed-eaters, none are estrildids: Te “Broad-shafted” (Sahel Paradise) and As mentioned in Part I, the inclusion of one or more New “Red-billed” (Pin-tailed) “Widahs”, and the “Crimson-collared World Scarlet Ibises in the collection that included “Senegal Widah” (Euplectes ardens). Te estrildids are represented by Java Finches” received at Peale’s Museum in 1805 (Sellers, 1979, Sparrows and Strawberry Finches (“Amandava, or Avodavine 206) might imply some connection with the “triangle trade” Finch”) and what Mann (1848) refers to as the “Senegal Finch, in African slaves. In 1807 the US Congress passed an act or Spice Bird” but states is “Found in various parts of Asia”! prohibiting the importation of slaves, which went into efect in One might gather Mann (who did not use Linnaean names in 1808. Tereafter, the US had limited direct trade with Africa this book) was discussing the Spice Finch (Nutmeg Mannikin) for the rest of the 19th Century, with New England ship owners (Lonchura punctulata) but his description does not ft at all: turning their attention to whaling in the Pacifc and the Arctic, and trade with China and Japan. “Tis pretty little songster is still smaller than the Amandava, and its note, although not quite so loud, is much more A few African birds continued to arrive in America in the frst harmonious. -

P. 1 SC58 Doc. 23 CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL TRADE

SC58 Doc. 23 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fifty-eighth meeting of the Standing Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 6-10 July 2009 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Compliance and enforcement ENFORCEMENT MATTERS 1. This document has been prepared by the Secretariat. Alerts 2. Since the 57th meeting of the Standing Committee (Geneva, July 2008), the Secretariat has issued Alerts on the following subjects: – Combating illicit trade in great apes; – Illegal trade in falcons; and – Illegal trade in caviar to the yachting community. CITES Enforcement Expert Group 3. At its 14th meeting (The Hague, 2007), the Conference of the Parties adopted Decisions 14.31 (Gathering and analysis of data on illicit trade), 14.33 (Enforcement Expert Group) and 14.72 (Asian big cats), which all require work to be conducted by the CITES Enforcement Expert Group. Decisions 14.32 and 14.34 direct the Standing Committee to consider the report of the Secretariat relating to the Group’s activities. 4. The Secretariat encountered several problems in identifying a venue for the CITES Enforcement Expert Group to meet and this was not resolved until March 2009. The Group will meet at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory but not until early June 2009. It will not, consequently, be possible for the Secretariat to prepare a report on the Group’s activities in time to meet the usual deadline for circulation of Standing Committee documents for the present meeting. The Secretariat will therefore either submit a written document after the deadline or an oral report at the meeting.