Wave Transformation Over a Barrier Reef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observation of Rip Currents by Synthetic Aperture Radar

OBSERVATION OF RIP CURRENTS BY SYNTHETIC APERTURE RADAR José C.B. da Silva (1) , Francisco Sancho (2) and Luis Quaresma (3) (1) Institute of Oceanography & Dept. of Physics, University of Lisbon, 1749-016 Lisbon, Portugal (2) Laboratorio Nacional de Engenharia Civil, Av. do Brasil, 101 , 1700-066, Lisbon, Portugal (3) Instituto Hidrográfico, Rua das Trinas, 49, 1249-093 Lisboa , Portugal ABSTRACT Rip currents are near-shore cellular circulations that can be described as narrow, jet-like and seaward directed flows. These flows originate close to the shoreline and may be a result of alongshore variations in the surface wave field. The onshore mass transport produced by surface waves leads to a slight increase of the mean water surface level (set-up) toward the shoreline. When this set-up is spatially non-uniform alongshore (due, for example, to non-uniform wave breaking field), a pressure gradient is produced and rip currents are formed by converging alongshore flows with offshore flows concentrated in regions of low set-up and onshore flows in between. Observation of rip currents is important in coastal engineering studies because they can cause a seaward transport of beach sand and thus change beach morphology. Since rip currents are an efficient mechanism for exchange of near-shore and offshore water, they are important for across shore mixing of heat, nutrients, pollutants and biological species. So far however, studies of rip currents have mainly relied on numerical modelling and video camera observations. We show an ENVISAT ASAR observation in Precision Image mode of bright near-shore cell-like signatures on a dark background that are interpreted as surface signatures of rip currents. -

Part III-2 Longshore Sediment Transport

Chapter 2 EM 1110-2-1100 LONGSHORE SEDIMENT TRANSPORT (Part III) 30 April 2002 Table of Contents Page III-2-1. Introduction ............................................................ III-2-1 a. Overview ............................................................. III-2-1 b. Scope of chapter ....................................................... III-2-1 III-2-2. Longshore Sediment Transport Processes ............................... III-2-1 a. Definitions ............................................................ III-2-1 b. Modes of sediment transport .............................................. III-2-3 c. Field identification of longshore sediment transport ........................... III-2-3 (1) Experimental measurement ............................................ III-2-3 (2) Qualitative indicators of longshore transport magnitude and direction ......................................................... III-2-5 (3) Quantitative indicators of longshore transport magnitude ..................... III-2-6 (4) Longshore sediment transport estimations in the United States ................. III-2-7 III-2-3. Predicting Potential Longshore Sediment Transport ...................... III-2-7 a. Energy flux method .................................................... III-2-10 (1) Historical background ............................................... III-2-10 (2) Description ........................................................ III-2-10 (3) Variation of K with median grain size................................... III-2-13 (4) Variation of K with -

NWS Melbourne Marine Web Letter August 2013 (For Marine Forecast Questions 24/7: Call 321-255-0212, Ext

NWS Melbourne Marine Web Letter August 2013 (For Marine Forecast Questions 24/7: call 321-255-0212, ext. 2) Marine Links relevant to East Central Florida Buoy 41010 It is hoped that this buoy, which went adrift in February, will be redeployed by mid to late September. Additional Marine Observations I’ve added a web page that has most of the marine observations along the east coast. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/mlb/?n=marob Note that wind/wave data became available at Sebastian Inlet via the National Data Buoy Center earlier this year. There are also some web cams with wind data. One, at Jensen Beach, has wave data too. Upwelling Some on again, off again upwelling occurred over the continental shelf this summer. This is not unusual. South to southeast winds (near shore parallel) are the primary cause of periodic upwelling. In some years, these winds are persistent and stronger than normal, which produces more prolific upwelling. In 2003, water temps in the upper 50s occurred in mid August at Daytona Beach! Typically the upwelling diminishes by late August or September. Nearshore Wave Prediction System We will soon upgrade our nearshore wave model (SWAN) to the Nearshore Wave Prediction System (NWPS). One enhancement is that Gulf Stream data will be incorporated back into the wave model. This will allow us to give better estimates for the position of the west wall of the Gulf Stream. The wave model will again be able to generate higher wave heights in the Gulf Stream during northerly wind surges. Hopefully, this functionality will be ready by Fall when cold fronts start moving through again. -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

Circulation-Wave Coupling with a Wave Parameterization for the Idealized California Coastal Region

Circulation-Wave Coupling With a Wave Parameterization For the Idealized California Coastal Region Le Ly and Curt Collins Dept. of Oceanography Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA 93043 1. Introduction atmospheric model), POM (Princeton Ocean Momentum and energy transfers across the air- Model; Blumberg and Mellor, 1987), and WAM sea interface under realistic ocean conditions are wave model (Wilczak et al., 1999), and an important not only in theoretical studies, but also atmosphere-POM-WAM for the Mediterranean in many applications including marine region (Lionello et al., 1999). atmospheric and oceanic forecasts and climate Based on a new concept of oceanic turbulence modeling on all scales. Surface breaking waves and a wave breaking condition of the linear wave are believed to be an important supplier of theory, a surface wave parameterization is turbulent energy besides shear production of the developed and presented. This wave classical turbulence theory. Waves contain a parameterization with wave-dependent roughness considerable amount of momentum and energy, is tested against available data on wave- and they redistribute these quantities over great dependent turbulence dissipation, roughness distances. Wind waves supply energy for length, drag coefficient, and momentum fluxes turbulence due to breaking. Ocean waves strongly using a coupled air-wave-sea model. We also effect the air-sea system on all scale. A part of the present a circulation-wave coupling study using a energy and momentum is transferred directly wave dependent roughness (Ly and Garwood, from the atmosphere to ocean currents while 2000) and taking the wind-wave-turbulence- another part is transferred to surface waves. The current relationship into account. -

OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen

11-14 May Bremen Germany Final Program OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen Balancing technology with future needs May 11th – 14th 2009 in Bremen, Germany Contents Welcome from the General Chair 2 Welcome 3 Useful Adresses & Phone Numbers 4 Conference Information 6 Social Events 9 Tourism Information 10 Plenary Session 12 Tutorials 15 Technical Program 24 Student Poster Program 54 Exhibitor Booth List 57 Exhibitor Profiles 63 Exhibit Floor Plan 94 Congress Center Bremen 96 OCEANS ´09 IEEE Bremen 1 Welcome from the General Chair WELCOME FROM THE GENERAL CHAIR In the Earth system the ocean plays an important role through its intensive interactions with the atmosphere, cryo- sphere, lithosphere, and biosphere. Energy and material are continually exchanged at the interfaces between water and air, ice, rocks, and sediments. In addition to the physical and chemical processes, biological processes play a significant role. Vast areas of the ocean remain unexplored. Investigation of the surface ocean is carried out by satellites. All other observations and measurements have to be carried out in-situ using research vessels and spe- cial instruments. Ocean observation requires the use of special technologies such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), towed camera systems etc. Seismic methods provide the foundation for mapping the bottom topography and sedimentary structures. We cordially welcome you to the international OCEANS ’09 conference and exhibition, to the world’s leading conference and exhibition in ocean science, engineering, technology and management. OCEANS conferences have become one of the largest professional meetings and expositions devoted to ocean sciences, technology, policy, engineering and education. -

Assessing Long-Term Changes in the Beach Width of Reef Islands Based on Temporally Fragmented Remote Sensing Data

Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 6961-6987; doi:10.3390/rs6086961 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Assessing Long-Term Changes in the Beach Width of Reef Islands Based on Temporally Fragmented Remote Sensing Data Thomas Mann 1,* and Hildegard Westphal 1,2 1 Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology, Fahrenheitstrasse 6, D-28359 Bremen, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Geosciences, University of Bremen, D-28359 Bremen, Germany * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-421-2380-0132; Fax: +49-421-2380-030. Received: 30 May 2014; in revised form: 7 July 2014 / Accepted: 18 July 2014 / Published: 25 July 2014 Abstract: Atoll islands are subject to a variety of processes that influence their geomorphological development. Analysis of historical shoreline changes using remotely sensed images has become an efficient approach to both quantify past changes and estimate future island response. However, the detection of long-term changes in beach width is challenging mainly for two reasons: first, data availability is limited for many remote Pacific islands. Second, beach environments are highly dynamic and strongly influenced by seasonal or episodic shoreline oscillations. Consequently, remote-sensing studies on beach morphodynamics of atoll islands deal with dynamic features covered by a low sampling frequency. Here we present a study of beach dynamics for nine islands on Takú Atoll, Papua New Guinea, over a seven-decade period. A considerable chronological gap between aerial photographs and satellite images was addressed by applying a new method that reweighted positions of the beach limit by identifying “outlier” shoreline positions. -

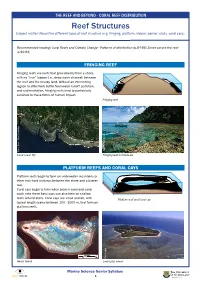

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island. -

Nature Parks Snorkeling Surfing Fishing

Things to do in Florida Nature Parks Snorkeling Surfing Fishing Nature Parks Green Cay This nature center is the county’s newest nature canter that over- looks 100 acres of constructed wetland. Wakodahatchee Wetlands Is a park in Delray Beach with a three-quarter mile boardwalk that crosses between open water ponds and marches. Patch Reef Park & DeHoernle Park Parks in Boca Raton that have an abundant of sports and recreation facilities. Morikami Museum & Japanese Gardens The gardens at this Japanese cultural center in Delray Beach in- clude paradise garden, various styles of rock and Zen gardens, and a museum. Gumbo Limbo This Nature Center and Environmental Complex includes an indoor museum with fish tanks with fish, turtles, and other sea life. It is also known for rehabilitating and protecting sea turtles. *More information and website links are located on the last page. Snorkeling Blowing Rocks This is an environmental preserve on Jupiter Island in Hobe Sound. This peaceful, barrier island sanctuary is known for large-scale, native coastal habitat restoration. Lantana Beach Lantana is a coastal community in Palm Beach and 10 feet off shore there is a pretty good areas to snorkel. Red Reef Park A 67-acre oceanfront park in Boca Raton for swimming, snorkeling, and surf fishing that includes a nature center. Lauderdale-by-the-Sea Is known as “The Shore Diving Capital of South Florida”. There are two coral reef lines that are just a short swim from the beach. John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park The first undersea park that encompasses about 70 natural square miles. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

The Economic, Social and Icon Value of the Great Barrier Reef Acknowledgement

At what price? The economic, social and icon value of the Great Barrier Reef Acknowledgement Deloitte Access Economics acknowledges and thanks the Great Barrier Reef Foundation for commissioning the report with support from the National Australia Bank and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. In particular, we would like to thank the report’s Steering Committee for their guidance: Andrew Fyffe Prof. Ove Hoegh-Guldberg Finance Officer Director of the Global Change Institute Great Barrier Reef Foundation and Professor of Marine Science The University of Queensland Anna Marsden Managing Director Prof. Robert Costanza Great Barrier Reef Foundation Professor and Chair in Public Policy Australian National University James Bentley Manager Natural Value, Corporate Responsibility Dr Russell Reichelt National Australia Bank Limited Chairman and Chief Executive Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Keith Tuffley Director Stephen Fitzgerald Great Barrier Reef Foundation Director Great Barrier Reef Foundation Dr Margaret Gooch Manager, Social and Economic Sciences Stephen Roberts Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Director Great Barrier Reef Foundation Thank you to Associate Professor Henrietta Marrie from the Office of Indigenous Engagement at CQUniversity Cairns for her significant contribution and assistance in articulating the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander value of the Great Barrier Reef. Thank you to Ipsos Public Affairs Australia for their assistance in conducting the primary research for this study. We would also like -

The Physical Environment in Coral Reefs of the Tayrona National Natural Park (Colombian Caribbean) in Response to Seasonal Upwelling*

Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost. 43 (1) 137-157 ISSN 0122-9761 Santa Marta, Colombia, 2014 THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT IN CORAL REEFS OF THE TAYRONA NATIONAL NATURAL PARK (COLOMBIAN CARIBBEAN) IN RESPONSE TO SEASONAL UPWELLING* Elisa Bayraktarov1, 2, Martha L. Bastidas-Salamanca3 and Christian Wild1,4 1 Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Coral Reef Ecology Group (CORE), Fahrenheitstraße 6, D-28359 Bremen, Germany. [email protected], [email protected] 2 Present address: The University of Queensland, Global Change Institute, Brisbane QLD 4072, Australia 3 Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (Invemar), Calle 25 No. 2-55 Playa Salguero, Santa Marta, Colombia. [email protected] 4 University of Bremen, Faculty of Biology and Chemistry (FB2), D-28359 Bremen, Germany ABSTRACT Coral reefs are subjected to physical changes in their surroundings including wind velocity, water temperature, and water currents that can affect ecological processes on different spatial and temporal scales. However, the dynamics of these physical variables in coral reef ecosystems are poorly understood. In this context, Tayrona National Natural Park (TNNP) in the Colombian Caribbean is an ideal study location because it contains coral reefs and is exposed to seasonal upwelling that strongly changes all key physical factors mentioned above. This study therefore investigated wind velocity and water temperature over two years, as well as water current velocity and direction for representative months of each season at a wind- and wave-exposed and a sheltered coral reef site in one exemplary bay of TNNP using meteorological data, temperature loggers, and an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) in order to describe the spatiotemporal variations of the physical environment.