Reconstructive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovarian Cancer and Cervical Cancer

What Every Woman Should Know About Gynecologic Cancer R. Kevin Reynolds, MD The George W. Morley Professor & Chief, Division of Gyn Oncology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI What is gynecologic cancer? Cancer is a disease where cells grow and spread without control. Gynecologic cancers begin in the female reproductive organs. The most common gynecologic cancers are endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer and cervical cancer. Less common gynecologic cancers involve vulva, Fallopian tube, uterine wall (sarcoma), vagina, and placenta (pregnancy tissue: molar pregnancy). Ovary Uterus Endometrium Cervix Vagina Vulva What causes endometrial cancer? Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer: one out of every 40 women will develop endometrial cancer. It is caused by too much estrogen, a hormone normally present in women. The most common cause of the excess estrogen is being overweight: fat cells actually produce estrogen. Another cause of excess estrogen is medication such as tamoxifen (often prescribed for breast cancer treatment) or some forms of prescribed estrogen hormone therapy (unopposed estrogen). How is endometrial cancer detected? Almost all endometrial cancer is detected when a woman notices vaginal bleeding after her menopause or irregular bleeding before her menopause. If bleeding occurs, a woman should contact her doctor so that appropriate testing can be performed. This usually includes an endometrial biopsy, a brief, slightly crampy test, performed in the office. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers are detected before spread to other parts of the body occurs Is endometrial cancer treatable? Yes! Most women with endometrial cancer will undergo surgery including hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) in addition to removal of ovaries and lymph nodes. -

Chapter 28 *Lecture Powepoint

Chapter 28 *Lecture PowePoint The Female Reproductive System *See separate FlexArt PowerPoint slides for all figures and tables preinserted into PowerPoint without notes. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Introduction • The female reproductive system is more complex than the male system because it serves more purposes – Produces and delivers gametes – Provides nutrition and safe harbor for fetal development – Gives birth – Nourishes infant • Female system is more cyclic, and the hormones are secreted in a more complex sequence than the relatively steady secretion in the male 28-2 Sexual Differentiation • The two sexes indistinguishable for first 8 to 10 weeks of development • Female reproductive tract develops from the paramesonephric ducts – Not because of the positive action of any hormone – Because of the absence of testosterone and müllerian-inhibiting factor (MIF) 28-3 Reproductive Anatomy • Expected Learning Outcomes – Describe the structure of the ovary – Trace the female reproductive tract and describe the gross anatomy and histology of each organ – Identify the ligaments that support the female reproductive organs – Describe the blood supply to the female reproductive tract – Identify the external genitalia of the female – Describe the structure of the nonlactating breast 28-4 Sexual Differentiation • Without testosterone: – Causes mesonephric ducts to degenerate – Genital tubercle becomes the glans clitoris – Urogenital folds become the labia minora – Labioscrotal folds -

The Cyclist's Vulva

The Cyclist’s Vulva Dr. Chimsom T. Oleka, MD FACOG Board Certified OBGYN Fellowship Trained Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologist National Medical Network –USOPC Houston, TX DEPARTMENT NAME DISCLOSURES None [email protected] DEPARTMENT NAME PRONOUNS The use of “female” and “woman” in this talk, as well as in the highlighted studies refer to cis gender females with vulvas DEPARTMENT NAME GOALS To highlight an issue To discuss why this issue matters To inspire future research and exploration To normalize the conversation DEPARTMENT NAME The consensus is that when you first start cycling on your good‐as‐new, unbruised foof, it is going to hurt. After a “breaking‐in” period, the pain‐to‐numbness ratio becomes favourable. As long as you protect against infection, wear padded shorts with a generous layer of chamois cream, no underwear and make regular offerings to the ingrown hair goddess, things are manageable. This is wrong. Hannah Dines British T2 trike rider who competed at the 2016 Summer Paralympics DEPARTMENT NAME MY INTRODUCTION TO CYCLING Childhood Adolescence Adult Life DEPARTMENT NAME THE CYCLIST’S VULVA The Issue Vulva Anatomy Vulva Trauma Prevention DEPARTMENT NAME CYCLING HAS POSITIVE BENEFITS Popular Means of Exercise Has gained popularity among Ideal nonimpact women in the past aerobic exercise decade Increases Lowers all cause cardiorespiratory mortality risks fitness DEPARTMENT NAME Hermans TJN, Wijn RPWF, Winkens B, et al. Urogenital and Sexual complaints in female club cyclists‐a cross‐sectional study. J Sex Med 2016 CYCLING ALSO PREDISPOSES TO VULVAR TRAUMA • Significant decreases in pudendal nerve sensory function in women cyclists • Similar to men, women cyclists suffer from compression injuries that compromise normal function of the main neurovascular bundle of the vulva • Buller et al. -

Pregnancy and Cesarean Delivery After Multimodal Therapy for Vulvar Carcinoma: a Case Report

MOLECULAR AND CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 5: 583-586, 2016 Pregnancy and cesarean delivery after multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma: A case report KUNIAKI TORIYABE1,2, HARUKI TANIGUCHI2, TOKIHIRO SENDA2,3, MASAKO NAKANO2, YOSHINARI KOBAYASHI2, MIHO IZAWA2, HIROHIKO TANAKA2, TETSUO ASAKURA2, TSUTOMU TABATA1 and TOMOAKI IKEDA1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu, Mie 514-8507; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie Prefectural General Medical Center, Yokkaichi, Mie 510-8561; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kinan Hospital, Mihama, Mie 519-5293, Japan Received November 4, 2015; Accepted September 12, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/mco.2016.1021 Abstract. Reports of pregnancy following treatment for vulvectomy, may have an increased incidence of caesarean vulvar carcinoma are extremely uncommon, as the main delivery (2). In the literature, vulvar scarring following radical problem of subsequent pregnancy is vulvar scarring following vulvectomy was the major reason for pregnant women under- radical surgery. We herein report the case of a patient who was going caesarean section (2-7). To date, no cases of pregnancy diagnosed with stage I squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva following vulvar carcinoma have been reported in patients at the age of 17 years and was treated with multimodal therapy, who had undergone surgery and radiotherapy. including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, wide local excision with We herein describe a case in which caesarean section was bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection and adjuvant radio- performed due to the presence of extensive vulvar scarring therapy. The patient became pregnant spontaneously 9 years following multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma, including after her initial diagnosis and the antenatal course was good, chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. -

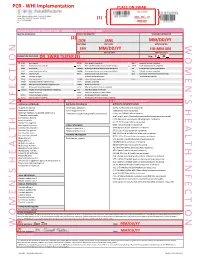

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra Explanation Please View Our Editing File Before Studying This Lecture to Check for Any Changes

Color Code Important Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Please view our Editing File before studying this lecture to check for any changes. Objectives At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to describe the: ✓ Boundaries of the perineum. ✓ Division of perineum into two triangles. ✓ Boundaries & Contents of anal & urogenital triangles. ✓ Lower part of Anal canal. ✓ Boundaries & contents of Ischiorectal fossa. ✓ Innervation, Blood supply and lymphatic drainage of perineum. Lecture Outline ‰ Introduction: • The trunk is divided into 4 main cavities: thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, and perineal. (see image 1) • The pelvis has an inlet and an outlet. (see image 2) The lowest part of the pelvic outlet is the perineum. • The perineum is separated from the pelvic cavity superiorly by the pelvic floor. • The pelvic floor or pelvic diaphragm is composed of muscle fibers of the levator ani, the coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue. (see image 3) We will talk about them more in the next lecture. Image (1) Image (2) Image (3) Note: this image is seen from ABOVE Perineum (In this lecture the boundaries and relations are important) o Perineum is the region of the body below the pelvic diaphragm (The outlet of the pelvis) o It is a diamond shaped area between the thighs. Boundaries: (these are the external or surface boundaries) Anteriorly Laterally Posteriorly Medial surfaces of Intergluteal folds Mons pubis the thighs or cleft Contents: 1. Lower ends of urethra, vagina & anal canal 2. External genitalia 3. Perineal body & Anococcygeal body Extra (we will now talk about these in the next slides) Perineum Extra explanation: The perineal body is an irregular Perineal body fibromuscular mass. -

Understanding Cancer of the Vulva

Understanding Cancer of the Vulva An information sheet for women with cancer, their families and friends. This information has been prepared to help you If something goes wrong with the genes that understand more about cancer of the vulva control a cell, that cell may start behaving (vulvar cancer). It is an introduction to the strangely. Instead of growing normally, it may diagnosis, treatment and effects of this cancer. grow and divide in an uncontrolled way, forming a mass of cells. The mass of cells looks We cannot advise you about the best treatment and feels like a lump, and is called a tumour. for you. You need to discuss this with your doctors. However, we hope this information A tumour can be benign (not cancer) or it can will answer some of your questions and help be malignant (cancer). The difference is that you think about the questions you want to ask benign tumours do not spread to other parts of your doctors. the body, while malignant tumours can. For more detailed information on cancer of the A malignant tumour is made up of cancer cells. vulva, you may wish to contact the Cancer When it first develops, the tumour stays in one Council Helpline on 13 11 20 or refer to the place. This is called the primary tumour. list of recommended websites under the heading Information on the Internet on the If the cancer cells that make up the primary back page of this booklet. tumour are not treated, they may start to spread to other areas of the body and form new tumours. -

University Microfilms 300 North 2Eeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns ...tch may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)''. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Transabdominal Extraperitoneal Section of the Obturator Nerve Trunk Paul H

TRANSABDOMINAL EXTRAPERITONEAL SECTION OF THE OBTURATOR NERVE TRUNK PAUL H. HARMON, M.D. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Permanente Hospitals and The Permanente Foundation, Oakland, California (Received for publication September 8, 1949) POPULAR method of interrupting section of the obturator nerve is to section its many peripheral branches high in the medial thigh as A originally described by Stoffel 6,7 in 1910. However, obturator nerve section in the thigh is frequently not as effective as section of the trunk higher because of accessory obturator nerves and branches of the main obturator trunk which may originate within the abdomen and pursue a variable peripheral course. Selig4'~ in 1913 and 1914 reported an anatomical study demonstrating the possibility of low intrapelvic extraperitoneal section of the obturator trunk. A number of authors (reviewed by Chandler and Seidler2 and by Wis- chnewsky s) have reported on the use of this technique. Chandler and Seidler2 reported 84 eases in 1939, in which the nerve was approached through a lower abdominal incision, just lateral to the lower border of the rectus muscle. In cases of bilateral section of the nerve these authors made a trans- verse skin incision with vertical deep dissection on the lateral side of each rectus abdominis muscle. Bonne0 described a lateral iliolumbar approach through which the obturator nerve was located high beneath the iliopsoas muscle. The disadvantage of this technique is the lengthy incision and deep dissection. Recently, Freeman 3 reported the combined section of the obtu- rator and femoral nerves in paraplegics, through a single vertical incision which crossed Poupart's ligament. -

Clinical Pelvic Anatomy

SECTION ONE • Fundamentals 1 Clinical pelvic anatomy Introduction 1 Anatomical points for obstetric analgesia 3 Obstetric anatomy 1 Gynaecological anatomy 5 The pelvic organs during pregnancy 1 Anatomy of the lower urinary tract 13 the necks of the femora tends to compress the pelvis Introduction from the sides, reducing the transverse diameters of this part of the pelvis (Fig. 1.1). At an intermediate level, opposite A thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy is essential for the third segment of the sacrum, the canal retains a circular clinical practice. Not only does it facilitate an understanding cross-section. With this picture in mind, the ‘average’ of the process of labour, it also allows an appreciation of diameters of the pelvis at brim, cavity, and outlet levels can the mechanisms of sexual function and reproduction, and be readily understood (Table 1.1). establishes a background to the understanding of gynae- The distortions from a circular cross-section, however, cological pathology. Congenital abnormalities are discussed are very modest. If, in circumstances of malnutrition or in Chapter 3. metabolic bone disease, the consolidation of bone is impaired, more gross distortion of the pelvic shape is liable to occur, and labour is likely to involve mechanical difficulty. Obstetric anatomy This is termed cephalopelvic disproportion. The changing cross-sectional shape of the true pelvis at different levels The bony pelvis – transverse oval at the brim and anteroposterior oval at the outlet – usually determines a fundamental feature of The girdle of bones formed by the sacrum and the two labour, i.e. that the ovoid fetal head enters the brim with its innominate bones has several important functions (Fig. -

The Pyramidalis–Anterior Pubic Ligament–Adductor Longus Complex (PLAC) and Its Role with Adductor Injuries: a New Anatomical Concept

The pyramidalis-anterior pubic ligament-adductor longus complex (PLAC) and its role with adductor injuries a new anatomical concept Schilders, Ernest; Bharam, Srino; Golan, Elan; Dimitrakopoulou, Alexandra; Mitchell, Adam; Spaepen, Mattias; Beggs, Clive; Cooke, Carlton; Holmich, Per Published in: Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy DOI: 10.1007/s00167-017-4688-2 Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Schilders, E., Bharam, S., Golan, E., Dimitrakopoulou, A., Mitchell, A., Spaepen, M., Beggs, C., Cooke, C., & Holmich, P. (2017). The pyramidalis-anterior pubic ligament-adductor longus complex (PLAC) and its role with adductor injuries: a new anatomical concept. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 25(12), 3969- 3977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-017-4688-2 Download date: 03. okt.. 2021 Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc DOI 10.1007/s00167-017-4688-2 HIP The pyramidalis–anterior pubic ligament–adductor longus complex (PLAC) and its role with adductor injuries: a new anatomical concept Ernest Schilders1,2,3 · Srino Bharam3,4 · Elan Golan5 · Alexandra Dimitrakopoulou2,6 · Adam Mitchell7 · Mattias Spaepen8 · Clive Beggs2 · Carlton Cooke9 · Per Holmich10,11 Received: 29 April 2017 / Accepted: 16 August 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Results The pyramidalis is the only abdominal muscle Purpose Adductor longus injuries are complex. The anterior to the pubic bone and was found bilaterally in all confict between views in the recent literature and various specimens. It arises from the pubic crest and anterior pubic nineteenth-century anatomy books regarding symphyseal ligament and attaches to the linea alba on the medial border. -

Divarication of Rectus Abdominis Muscle Postpartum Information And

Divarication of rectus abdominis muscle éçëíé~êíìã Information and advice What is divarication and why do I have it? For some women, pregnancy can cause separation of the stomach muscles which can also be referred to as Diastasis Recti. The right and left sides of the rectus abdominis muscle (‘six pack muscle’) separate at the linea alba which connects the two sides of the muscle together. Rectus Abdominis Abdominal Separation (approximate representation) (approximate representation) It is normal in pregnancy for the stomach muscles to separate as the uterus continues to grow and push on the abdominal wall. This only becomes problematic in pregnancy when the abdominal wall is weak. The abdominal muscles are an important muscle group in supporting your back. If they remain weak after pregnancy, it can increase your risk of suffering from back pain. Diagnosis – how do I know if I have a separation? Most pregnant women will have a separation of one or two fingers width after pregnancy and this is normal. In most cases this will spontaneously recover and will not cause you any problems. However if the gap is more than two fingers width and you have a visible doming at the midline, you may have a divarication of the abdominis muscle and would benefit from seeing a physiotherapist. You can measure this yourself by lying with your knees bent and using your fingers as a guide at the level of your belly button. What can I do to help myself? Try to avoid all activities which place a lot of pressure on your abdominal wall, or cause an over stretch to your stomach.