' and ''The Cut Below'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovarian Cancer and Cervical Cancer

What Every Woman Should Know About Gynecologic Cancer R. Kevin Reynolds, MD The George W. Morley Professor & Chief, Division of Gyn Oncology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI What is gynecologic cancer? Cancer is a disease where cells grow and spread without control. Gynecologic cancers begin in the female reproductive organs. The most common gynecologic cancers are endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer and cervical cancer. Less common gynecologic cancers involve vulva, Fallopian tube, uterine wall (sarcoma), vagina, and placenta (pregnancy tissue: molar pregnancy). Ovary Uterus Endometrium Cervix Vagina Vulva What causes endometrial cancer? Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer: one out of every 40 women will develop endometrial cancer. It is caused by too much estrogen, a hormone normally present in women. The most common cause of the excess estrogen is being overweight: fat cells actually produce estrogen. Another cause of excess estrogen is medication such as tamoxifen (often prescribed for breast cancer treatment) or some forms of prescribed estrogen hormone therapy (unopposed estrogen). How is endometrial cancer detected? Almost all endometrial cancer is detected when a woman notices vaginal bleeding after her menopause or irregular bleeding before her menopause. If bleeding occurs, a woman should contact her doctor so that appropriate testing can be performed. This usually includes an endometrial biopsy, a brief, slightly crampy test, performed in the office. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers are detected before spread to other parts of the body occurs Is endometrial cancer treatable? Yes! Most women with endometrial cancer will undergo surgery including hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) in addition to removal of ovaries and lymph nodes. -

The Cyclist's Vulva

The Cyclist’s Vulva Dr. Chimsom T. Oleka, MD FACOG Board Certified OBGYN Fellowship Trained Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologist National Medical Network –USOPC Houston, TX DEPARTMENT NAME DISCLOSURES None [email protected] DEPARTMENT NAME PRONOUNS The use of “female” and “woman” in this talk, as well as in the highlighted studies refer to cis gender females with vulvas DEPARTMENT NAME GOALS To highlight an issue To discuss why this issue matters To inspire future research and exploration To normalize the conversation DEPARTMENT NAME The consensus is that when you first start cycling on your good‐as‐new, unbruised foof, it is going to hurt. After a “breaking‐in” period, the pain‐to‐numbness ratio becomes favourable. As long as you protect against infection, wear padded shorts with a generous layer of chamois cream, no underwear and make regular offerings to the ingrown hair goddess, things are manageable. This is wrong. Hannah Dines British T2 trike rider who competed at the 2016 Summer Paralympics DEPARTMENT NAME MY INTRODUCTION TO CYCLING Childhood Adolescence Adult Life DEPARTMENT NAME THE CYCLIST’S VULVA The Issue Vulva Anatomy Vulva Trauma Prevention DEPARTMENT NAME CYCLING HAS POSITIVE BENEFITS Popular Means of Exercise Has gained popularity among Ideal nonimpact women in the past aerobic exercise decade Increases Lowers all cause cardiorespiratory mortality risks fitness DEPARTMENT NAME Hermans TJN, Wijn RPWF, Winkens B, et al. Urogenital and Sexual complaints in female club cyclists‐a cross‐sectional study. J Sex Med 2016 CYCLING ALSO PREDISPOSES TO VULVAR TRAUMA • Significant decreases in pudendal nerve sensory function in women cyclists • Similar to men, women cyclists suffer from compression injuries that compromise normal function of the main neurovascular bundle of the vulva • Buller et al. -

Pregnancy and Cesarean Delivery After Multimodal Therapy for Vulvar Carcinoma: a Case Report

MOLECULAR AND CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 5: 583-586, 2016 Pregnancy and cesarean delivery after multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma: A case report KUNIAKI TORIYABE1,2, HARUKI TANIGUCHI2, TOKIHIRO SENDA2,3, MASAKO NAKANO2, YOSHINARI KOBAYASHI2, MIHO IZAWA2, HIROHIKO TANAKA2, TETSUO ASAKURA2, TSUTOMU TABATA1 and TOMOAKI IKEDA1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu, Mie 514-8507; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mie Prefectural General Medical Center, Yokkaichi, Mie 510-8561; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kinan Hospital, Mihama, Mie 519-5293, Japan Received November 4, 2015; Accepted September 12, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/mco.2016.1021 Abstract. Reports of pregnancy following treatment for vulvectomy, may have an increased incidence of caesarean vulvar carcinoma are extremely uncommon, as the main delivery (2). In the literature, vulvar scarring following radical problem of subsequent pregnancy is vulvar scarring following vulvectomy was the major reason for pregnant women under- radical surgery. We herein report the case of a patient who was going caesarean section (2-7). To date, no cases of pregnancy diagnosed with stage I squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva following vulvar carcinoma have been reported in patients at the age of 17 years and was treated with multimodal therapy, who had undergone surgery and radiotherapy. including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, wide local excision with We herein describe a case in which caesarean section was bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection and adjuvant radio- performed due to the presence of extensive vulvar scarring therapy. The patient became pregnant spontaneously 9 years following multimodal therapy for vulvar carcinoma, including after her initial diagnosis and the antenatal course was good, chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. -

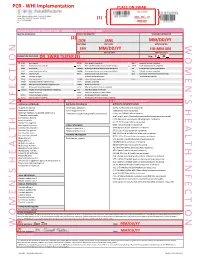

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra Explanation Please View Our Editing File Before Studying This Lecture to Check for Any Changes

Color Code Important Female Perineum Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Please view our Editing File before studying this lecture to check for any changes. Objectives At the end of the lecture, the student should be able to describe the: ✓ Boundaries of the perineum. ✓ Division of perineum into two triangles. ✓ Boundaries & Contents of anal & urogenital triangles. ✓ Lower part of Anal canal. ✓ Boundaries & contents of Ischiorectal fossa. ✓ Innervation, Blood supply and lymphatic drainage of perineum. Lecture Outline ‰ Introduction: • The trunk is divided into 4 main cavities: thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, and perineal. (see image 1) • The pelvis has an inlet and an outlet. (see image 2) The lowest part of the pelvic outlet is the perineum. • The perineum is separated from the pelvic cavity superiorly by the pelvic floor. • The pelvic floor or pelvic diaphragm is composed of muscle fibers of the levator ani, the coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue. (see image 3) We will talk about them more in the next lecture. Image (1) Image (2) Image (3) Note: this image is seen from ABOVE Perineum (In this lecture the boundaries and relations are important) o Perineum is the region of the body below the pelvic diaphragm (The outlet of the pelvis) o It is a diamond shaped area between the thighs. Boundaries: (these are the external or surface boundaries) Anteriorly Laterally Posteriorly Medial surfaces of Intergluteal folds Mons pubis the thighs or cleft Contents: 1. Lower ends of urethra, vagina & anal canal 2. External genitalia 3. Perineal body & Anococcygeal body Extra (we will now talk about these in the next slides) Perineum Extra explanation: The perineal body is an irregular Perineal body fibromuscular mass. -

Determinants Towards Female Cosmetic Surgery

1 Genital Anxiety and the Quest for the Perfect Vulva: A Feminist Analysis of Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery Ariana Keil 95863710 Women and the Body- Professor Susan Greenhalgh UCI March, 2010 2 Genital Anxiety and the Quest for the Perfect Vulva: A Feminist Analysis of Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery Female genital cosmetic surgery procedures are relatively new, but they are swiftly growing in popularity (Braun, 2005). As they become more commonplace, they play an increasingly large role in perpetuating the very psychological pain they purpose to treat, that of genital anxieties. This paper will examine the genesis of female genital cosmetic surgery within the larger framework of the cosmetic surgery apparatus, including the perspectives and practices of the physicians who perform female genital cosmetic surgery. This paper will address the range of normality observed in women’s genitals, the cultural construction of the ideal vulva and the roll of pornography in popularizing this construction. The purpose of this paper is to examine women’s genital anxieties, their sources, and what, in conjunction with these anxieties, will lead a woman to choose female genital cosmetic surgery. It will examine the cultural sources of genital anxieties, focusing on cultural concepts and representations of the ideal vulva and labia, and analyze these from a feminist perspective. Cultural ideals and models of femininity, and how these affect concepts of how women’s genitals should look will be addressed, as will the current disseminator of these visual models, pornography. The psychological and lifestyle ramifications of women’s genital anxieties will be examined, showing how these anxieties have real and damaging effects on women’s lives, damage which is only heightened by a cultural acceptance of plastic surgery as a legitimate way to correct these anxieties. -

Aesthetic Surgery of the Female Genitalia

Aesthetic Surgery of the Female Genitalia Julie M.L.C.L. Dobbeleir, M.D.,1 Koenraad Van Landuyt, M.D., Ph.D.,2 and Stan J. Monstrey, M.D., Ph.D.2 ABSTRACT Aesthetic genital surgery seems to have become a fashionable issue nowadays. Many procedures and techniques have been described these last years, but very few long- term results or follow up studies are available. The novelty of this aspect of plastic surgery and the lack of evidence-based interventions, have led to a comparison with female genital mutilation. In this article, the authors provide an overview of the possible surgical procedures as well as the general principles of aesthetic surgery of the female genitalia. KEYWORDS:Genital surgery, genital cutting, labioplasty, vaginal tightening Aesthetic surgery of the female genitalia is a rium, many questions have been raised, regarding tech- much discussed topic in the popular press as well as the nical issues, indications, and—not in the least–ethics, scientific journals. It seems to be fashionable for men but few scientific answers are available. and women of today’s world to have their genitals As for every new specialty, guidelines need to be altered. set up and long-term studies are a necessity. Complicat- Although it might strike as a new trend quickly ing the issue even more is the fact that genital beauty is arising in all layers of society, it has been around for ages. very culturally defined. The same template and indica- The genital ideal may differ historically and cross- tions cannot be used cross-culturally. -

Chronic Infections of the Vulva Or Vagina

Chronic Infection Persistent or recurrent vaginal infections may cause daily or episodic symptoms of itching, irritation or burning. Not all women have persistent discharge from the vagina. Research supports that approximately 5% of women will suffer from recurrent infections. The most common recurrent infections are: 1. Yeast 2. Bacterial Vaginosis 3. Trichomonas Yeast Infection Yeast infections are common; approximately 20% of all women will experience one in their lifetime. Diabetes, pregnancy, antibiotic use and immuno-suppression are risk factors that predispose women to yeast infections. Yeast infections are not sexually transmitted. Although most women worry that their partner may be a source of re- infectivity, the penis is not a reservoir. In addition, a diet high in refined sugar does not put a woman at risk for recurrence. For some women with chronic yeast infections, the symptoms may flare at the same time during the menstrual cycle. Some experience burning with urination or vaginal dryness. Intercourse may be painful. Recurrent infection is defined as 4 infections/year. Diagnosis is made from history and physical exam. Usually a special fungal culture is obtained to identify the yeast organism. If an acute infection is occurring, this is treated aggressively for 7-14days. Treatment is administered either orally or vaginally. Boric acid, a natural acid compound, can be used to effectively treat some resistant strains of yeast. Suppression may follow after treatment for the acute infection and may be recommended for up to 6 months. Most experience relief with long-term treatment, although the recurrence rate after suppression can be as high as 30%. -

A Human Rights-Based Approach to Mistreatment and Violence Against Women in Reproductive Health Services with a Focus on Childbirth and Obstetric Violence

United Nations A/74/137 General Assembly Distr.: General 11 July 2019 Original: English Seventy-fourth session Item 26 (a) of the preliminary list* Advancement of women: advancement of women A human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly the report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Dubravka Šimonović, submitted in accordance with Assembly resolution 71/170. * A/74/50. 19-11859 (E) 130819 *1911859* A/74/137 Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences on a human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence Summary • In the present report, the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences analyses the issue of mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence, as well as the root causes and structural issues that need to be addressed to combat such forms of mistreatment and violence. 2/23 19-11859 A/74/137 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................... 4 II. Activities ..................................................................... 4 III. A human rights-based approach to mistreatment and violence against women in reproductive health services with a focus on childbirth and obstetric violence ........................ 4 A. Introduction ............................................................... 4 B. Scope of the report ......................................................... 5 C. Manifestations of mistreatment and gender-based violence in reproductive health-care services and during facility-based childbirth ................................... -

Tumors of the Uterus, Vagina, and Vulva

Tumors of the Uterus, Vagina, and Vulva 803-808-7387 www.gracepets.com These notes are provided to help you understand the diagnosis or possible diagnosis of cancer in your pet. For general information on cancer in pets ask for our handout “What is Cancer”. Your veterinarian may suggest certain tests to help confirm or eliminate diagnosis, and to help assess treatment options and likely outcomes. Because individual situations and responses vary, and because cancers often behave unpredictably, science can only give us a guide. However, information and understanding for tumors in animals is improving all the time. We understand that this can be a very worrying time. We apologize for the need to use some technical language. If you have any questions please do not hesitate to ask us. What are these tumors? Most swellings and tumors of the uterus are not cancerous. The most common in the bitch is cystic endometrial hyperplasia (overgrowth of the inner lining of the uterus) due to hormone stimulation. Sometimes, this reaction is deeper in the muscle layers and is called ‘adenomyosis’. Secondary infection and inflammation then convert the endometrial hyperplasia into pyometra (literally pus in the womb). Cysts and polyps of the endometrium can also be part of the pyometra syndrome or be due to congenital abnormalities. They may persist when the cause is removed and may be multiple. Endometrial cancers may also be multiple. Benign adenomas of the endometrium are rare. Malignant tumors (adenocarcinomas) may spread (metastasize) to lymph nodes and lungs, often when the primary is still small in size. -

Vulvar Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Vulvar Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis Finding cancer early -- when it's small and before it has spread -- often allows for more treatment options. Some early cancers may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that's not always the case. ● Can Vulvar Cancer Be Found Early? ● Signs and Symptoms of Vulvar Cancers and Pre-Cancers ● Tests for Vulvar Cancer Stages and Outlook (Prognosis) After a cancer diagnosis, staging provides important information about the extent of cancer in the body and anticipated response to treatment. ● Vulvar Cancer Stages ● Survival Rates for Vulvar Cancer Questions to Ask About Vulvar Cancer Here are some questions you can ask your cancer care team to help you better understand your cancer diagnosis and treatment options. ● Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Vulvar Cancer 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Can Vulvar Cancer Be Found Early? Having pelvic exams and knowing any signs and symptoms of vulvar cancer greatly improve the chances of early detection and successful treatment. If you have any of the problems discussed in Signs and Symptoms of Vulvar Cancers and Pre-Cancers, you should see a doctor. If the doctor finds anything abnormal during a pelvic examination, you may need more tests to figure out what is wrong. This may mean referral to a gynecologist (specialist in problems of the female genital system). Knowing what to look for can sometimes help with early detection, but it is even better not to wait until you notice symptoms. -

STEPHANIE TILLMAN Chicago, IL · [email protected] Midwife · Writer · Speaker · Activist

STEPHANIE TILLMAN Chicago, IL · [email protected] Midwife · Writer · Speaker · Activist EDUCATION University of Chicago, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics July 2020-May 2021 Fellowship in Clinical Medical Ethics Yale University School of Nursing · New Haven, CT Grad. 2012 Masters of Science in Nursing, Nurse-Midwifery University of Michigan · Ann Arbor, MI Grad. 2007 Bachelor of the Arts, Global Health and Medical Anthropology CLINICAL EXPERIENCE University of Illinois Hospital · Chicago, IL Oct 2015 - present Certified Nurse Midwife (Previously Academic Hourly) Aug 2014 – Oct 2015 • Full-scope inpatient care including intrapartum, postpartum, and obstetric emergency room • Full-scope outpatient primary, obstetric, gynecologic, and postpartum care including IUD provision • Precept student Nurse Midwives, Nurse Practitioners, Family Medicine Residents and Medical Students Access Community Health Network · Chicago, IL Sept 2012 – Oct 2015 Certified Nurse Midwife • Full-scope inpatient care including intrapartum, postpartum, and OBER/triage • Full-scope outpatient primary, obstetric, gynecologic, and postpartum care including Centering Pregnancy® • Attended birth and precepted Midwifery, Medical, and obstetric Residents at Mount Sinai Hospital Saint Anthony Hospital · Chicago, IL Feb 2014 – June 2015 Certified Nurse Midwife (per diem) • Attending, Laborist, and surgical first assist on labor and delivery unit: intrapartum, postpartum, triage care forma · Chicago, IL May 2013 – Jan 2015 Midwife, Volunteer • Facilitate pregnancy