Songs on the Waves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Fylkingen's Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974

Fylkingen’s Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974 Teddy Hultberg Abstract In the 1960s the concept and the genre of “text-sound composition” were born in Sweden. Being an offspring of sound poetry in various forms and of the new electro- acoustic music of the post-war years, it took shape as an intermedia art form par excel- lence. This essay traces the emergence of text-sound in a Swedish context and especially its appearance at the internationally renowned text-sound festivals held at Fylkingen in Stockholm during the years 1968–1974. By the time the term was invented in the 1960, text-sound composition, as an aesthetic practice, was already an international phenomenon. The Swedish version of this intermedia genre was given an international plat- form through the famous text-sound festivals that were organised by Fylkingen in Stockholm between 1968 and 1974. Founded as a chamber music society in 1933, Fylkingen had at this time developed into an organisa- tion that promoted all the new events in music, dance and theatre. And in this context sound poetry and text-sound composition appeared to be typi- cal art forms of the time – art forms that would explore the interstices between word and sound, poetry and music, and which would further the investigation of the electro-acoustic landscape staked out in avant-garde music from the post-war period by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luciano Berio. In short, the history of text-sound composition can be seen as the history of how technology during the early 1960s changed the poetic expression when it opened the literary field to a new kind of sound poetry. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Conceiving Musical Transdialection

Conceiving Musical Transdialection By Richard Beaudoin, Harvard University and Joseph Moore, Amherst College Abstract: We illuminate the wandering notion of a musical transcription by reflecting on the various ways “transcription” and its cognates have been used in musical discourse, and by examining some notable 20th century transcriptions of J. S. Bach, which became increasingly loose through the decades. At root, musical transcription aims at preservation, but, as we bring out, exactly which musical ingredients are preserved across which transformations varies from transcriptional project to transcriptional project. We defend as intelligible one very interesting such project—we call it “transdialection”—by exploring an analogy with poetic translation, and by directly taking on some natural objections to it. We conclude that certain controversial transcriptions are justifiably and usefully so-called. 1 0. Transcription Traduced While it may not surprise you to learn that the first bit of music above is the opening of a chorale prelude by Baroque master, J. S. Bach, who would guess that the second bit is a so-called transcription of it? But it is—it’s a transcription by the contemporary British composer, Michael Finnissy. The two passages look very different from one another, even to those of us who don’t read music. And hearing the pieces will do little to dispel the shock, for here we have bits of music that seem worlds apart in their melodic makeup, harmonic content and rhythmic complexity. It’s a far cry from Bach’s steady tonality to Finnissy’s floating, tangled lines—a sonic texture in which, as one critic put it, real music is “mostly thrown into a seething undigested, unimagined heap of dyslexic clusters of multiple key- and time-proportions, as intricately enmeshed in the fetishism of the written notation as those 2 with notes derived from number-magic.”1 We’re more sympathetic to Finnissy’s music. -

Luciano Berio's Sequenza V Analyzed Along the Lines of Four Analytical

Peer-Reviewed Paper JMM: The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.9, Winter 2010 Luciano Berio’s Sequenza V analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer Niels Chr. Hansen, Royal Academy of Music Aarhus, Denmark and Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK Abstract In this paper, Luciano Berio’s ‘Sequenza V’ for solo trombone is analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer himself in an interview from 1980. It is argued that the piece in general can be interpreted as an exploration of the ‘morphological’ dimension involving transformation of the traditional image of the trombone as an instrument as well as of the performance context. The first kind of transformation is revealed by simultaneous singing and playing, continuous sounds and considerable use of polyphony, indiscrete pitches, plunger, flutter-tongue technique, and unidiomatic register, whereas the latter manifests itself in extra-musical elements of theatricality, especially with reference to clown acting. Such elements are evident from performance notes and notational practice, and they originate from biographical facts related to the compositional process and to Berio’s sources of inspiration. Key topics such as polyphony, amalgamation of voice and instrument, virtuosity, theatricality, and humor – of which some have been recognized as common to the Sequenza series in general – are explained in the context of the analytical model. As a final point, a revised version of the four-dimensional model is presented in which tension-inducing characteristics in the ‘pitch’, ‘temporal’ and ‘dynamic’ dimensions are grouped into ‘local’ and ‘global’ components to avoid tension conflicts within dimensions. -

Concert: King's Singers King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-24-2005 Concert: King's Singers King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation King's Singers, "Concert: King's Singers" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1606. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1606 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. SCHC)GI:; ()E "' ' ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 2005-6 . King's Singers David Hurley, cou_ntertenor .Robin Tyson, countertenor Paul Phoenix, tenor Philip Lawson, baritone · Christopher Gabbitas, baritone Stephen Connolly, bass Ford Hall Monday, October 24, 2005 8:15 p.m. ··1 r,,m...... .... c·'-1 \ ... -... -. ... .. -... .. l· ... Songs from the Auvergne La-bas, dans le Limousin Traditional . Une gentre bergere Arranged by S. Von Goff Richards L'eau de source Le baylere A la campagne · French chansons Dessus le marche d' Arras Orlandus La:ssus (1532-1594) Les yeulx bendez " Pierre Vermont (d. i532) Il est bel et bon Pierre Passereau (1:190-1547) Laguerre Clement Janequin � (1485-1558) Valentines A lover's journey- Four Valentines Libby Larsen (b. 1950) INTERMISSION Masterpiece Masterpiece (19.81) Paul Drayton (b. 1944) Arrangements in'Close Harmony Selections from the lighter side of the repertoire . Progra� is subject to 'change Photographic,. video, and sound recording and/ or tr�mitting devices are not permitted in the Whalen Center concert halls. -

Copyright Timothy Brennan Steeves 2020

i Copyright Timothy Brennan Steeves 2020 i ii Abstract Concertare and Conserere: Debate and Concord in the Twenty-first Century Violin Concerto by Timothy Brennan Steeves This document concerns the ways in which the relationship between the violin and orchestra in the violin concerto has changed in the first decades of the twenty-first century. Using the concerti of Unsuk Chin (2001), Jennifer Higdon (2008), and Esa- Pekka Salonen (2009) I show that composers have challenged but not abandoned the supremacy and centrality of the violin soloist. The role of the orchestra has been expanded, being given greater aesthetic and structural responsibility. The virtuosity expected of professional orchestra musicians is exploited with these composers frequently calling on secondary soloists. Chamber music and contrapuntal textures are also employed to relegate the violinist to a first among equals. These innovations and the resultant violinistic implications represent a new path forwards in the genre of the violin concerto. These composers are, however, cognizant of both tradition and the expectations of virtuoso soloists. Strides towards equality can be made, but a true, irrevocable hierarchical leveling is not achieved. This tension, the new balance of power, and their musical ramifications are the focus of this study. iii Acknowledgments This document is the culmination of many years of study, performance, reflection, and collaboration. Innumerable teachers, colleagues, and friends have contributed to my musical and intellectual development and it is impossible to thank everyone. Nevertheless, there are a few key people who deserve special recognition. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude for the guidance, support, expertise, and patience of my advisor Dr. -

Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice As Compositional Process in Berio's Sequenza I for Solo Flute

Chapter 11 Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice as Compositional Process in Berio’s Sequenza I for Solo Flute Irna Priore The ideal listener is the one who can catch all the implications; the ideal composer is the one who can control them. Luciano Berio, 18 August 1995 Introduction Luciano Berio’s first Sequenza dates from 1958 and was written for the Italian flutist Severino Gazzelloni (1919–92). The first Sequenza is an important work in many ways. It not only inaugurates the Sequenza series, but is also the third major work for unaccompanied flute in the twentieth century, following Varèse’s Density 21.5 (1936) and Debussy’s Syrinx (1913).1 Berio’s work for solo flute is an undeniable challenge for the interpreter because it is a virtuoso piece, it is written in proportional notation without barlines, and it is structurally ambiguous.2 It is well known that performances of this piece brought Berio much dissatisfaction, a fact that led to the publication of a new version by Universal Edition in 1992.3 This new edition was intended to supply a metrical understanding of the work, apparently lacking or too vaguely implied in the original score. However, while some aspects of the piece have been clarified by Berio himself, 1 A three-note chromatic motif has been observed running as a unifying thread in all three works. See Cynthia Folio, ‘Luciano Berio’s Sequenza for Flute: A Performance Analysis’, The Flutist Quarterly, 15/4 (1990), p. 18. 2 The observations regarding the difficulty of the work were compiled from informal interviews conducted between autumn 2003 and spring 2004 with professionals teaching in American universities and colleges, to whom I am indebted. -

American Music Review Formerly the Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter

American Music Review Formerly the Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XXXVIII, No. 1 Fall 2008 “Her Whimsy and Originality Really editorial flurry has facilitated many performances and first record- ings. The most noteworthy recent research on Beyer has been Amount to Genius”: New Biographical undertaken by Melissa de Graaf, whose work on the New York Research on Johanna Beyer Composers’ Forum events during the 1930s portrays Beyer’s public persona during the highpoint of her compositional career (see, for by Amy C. Beal example, de Graaf’s spring 2004 article in the I.S.A.M. Newsletter). Most musicologists I know have never heard of the German-born Beyond de Graaf’s work, we have learned little more about Beyer composer and pianist Johanna Magdalena Beyer (1888-1944), who since 1996. Yet it is clear that her compelling biography, as much as emigrated to the U.S. in 1923 and spent the rest of her life in New her intriguing compositional output, merits further attention. York City. During that period she composed over Beyer’s correspondence with Henry fifty works, including piano miniatures, instru- Cowell (held primarily at the New York mental solos, songs, string quartets, and pieces Public Library for the Performing Arts) for band, chorus, and orchestra. This body of helps us construct a better picture of her life work allies Beyer with the group known as the between February 1935, when her letters to “ultramodernists,” and it offers a further perspec- Cowell apparently began, and mid-1941, tive on the compositional style known as “dis- when their relationship ended. -

Luciano Berio, Max Richter, Paul Mccartney and More

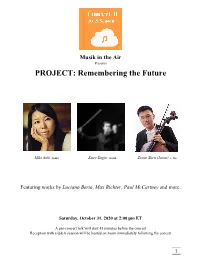

Musik in the Air Presents PROJECT: Remembering the Future Miki Aoki, piano Emre Engin, violin Zexun Shen (Jason), cello Featuring works by Luciano Berio, Max Richter, Paul McCartney and more. Saturday, October 31, 2020 at 2:00 pm ET A pre-concert talk will start 45 minutes before the concert Reception with a Q&A session will be hosted on zoom immediately following the concert 1 ♫ Program ♫ On the Nature of Daylight Max Richter (1966-0000) Zexun Shen (Jason), cello Miki Aoki, piano Selections from 6 Encores for Piano Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Wasserklavier Erdenklavier Luftklavier Feuerklavier Miki Aoki, piano Two Pieces for String Duo György Ligeti (1923-2006) Ballad and Dance Hommage à Hilding Rosenberg Emre Engin, violin Zexun Shen (Jason), cello A Leaf Paul McCartney (1942-0000) Andante semplice Poco piu mosso Allegro ritmico Andante Allegro ma non tanto Moderato Andante semplice II Miki Aoki, piano Mercy Max Richter (1966-0000) Emre Engin, violin Miki Aoki, piano Sequenza VIII for violin Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Emre Engin, violin 2 ♫ Concert in Brief ♫ This is the kind of program where the audience may wonder about the connection between a classical composer (Luciano Berio), One of the Beatles (Paul McCartney) and one of today’s most successful movie/TV series soundtrack composers (Max Richter). Luciano Berio, an avant-garde European composer (Italian) was born in 1925. It is hard to imagine that he had any connection to a group like the Beatles. It is surprising, but true that both sides had great admiration for each other. Paul McCartney was searching for new ideas for his music. -

Undergraduate Listening List

Undergraduate Composition Listening List Claude Debussy: Nocturnes (1899) CD 1073 M1003.D4 N64 Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (1912) CD 8960 M1625.S3 P5 Op. 21 Igor Stravinsky: Rite of Spring (1913) CD 5552 M1520.S9 S3 Bo2 Anton von Webern: Symphony, Op.21 (1929) CD 2566 M1001.W39 S9 1929 Ruth Crawford Seeger: String Quartet (1931) CD 8896 M452.S44 Q8 Alban Berg: Violin Concerto (1935) CD 5665 M1012.B47 Béla Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste (1936) CD 5590 M1105.B35M8 Bo Olivier Messiaen: Quartet for the End of Time (1941) CD 2292 M422.M48 Q3 Grażyna Bacewicz: Sonata per violino solo No. 2 (1958) Online recording: http://fsu.naxosmusiclibrary.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/catalogue/item.asp?cid=CSCD-95011 M42.B23S66 Elliott Carter: String Quartet #2 (1959) CD 3129 M452.C377 Q82 no. 2 Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, Nos. 2-3 (1962) Online recording: http://fsu.naxosmusiclibrary.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/catalogue/item.asp?cid=CHAN8983-84 M2013.B86 W4 Krzysztof Penderecki: St. Luke Passion (1966) Rec3160 SLP M2004.P46.P27 Witold Lutosławski: Livre (1968) CD 2286 M1045.L975.L58 Luciano Berio: Sinfonia, III – In ruhig fliessender Bewegung (1969) CD 8917 M1528.B475 S56 George Crumb: Ancient Voices of Children (1970) CD 9218 M1613.3.C92 A5 Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No.15 (1974) CD 7200 M452.S556 Q8 no. 15, op. 144 Louis Andriessen: De Staat (1972 – 1976) Rec 10095 SLP M1528.A52 S7 1992 John Corigliano: Clarinet Concerto (1977) CD 756 M1025.C67 C6 1993 Steve Reich: Octet (Eight Lines) (1979) CD1654 M885.R34 O37 Sofia Gubaidulina: