Copyright by Matthew Edward Krebs 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

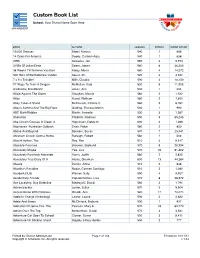

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

Qt2wn8v8p6.Pdf

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2wn8v8p6 Author Gomez, Isabel Cherise Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures by Isabel Cherise Gomez 2016 © Copyright by Isabel Cherise Gomez 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) by Isabel Cherise Gomez Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Efraín Kristal, Co-Chair Professor José Luiz Passos, Co-Chair What becomes visible when we read literary translations as gifts exchanged in a reciprocal symbolic economy? Figuring translations as gifts positions both source and target cultures as givers and recipients and supplements over-used translation metaphors of betrayal, plundering, submission, or fidelity. As Marcel Mauss articulates, the gift itself desires to be returned and reciprocated. My project maps out the Hemispheric Americas as an independent translation zone and highlights non-European translation norms. Portuguese and Spanish have been sidelined even from European translation studies: only in Mexico and Brazil do we see autochthonous translation theories in Spanish and Portuguese. Focusing on translation strategies that value ii taboo-breaking, I identify poet-translators in Mexico and Brazil who develop their own translation manuals. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Rock Legends TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk Cream - Fronted by Eric Clapton, Cream was the prototypical power trio, playing a mix of blues, Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the rock and psychedelia while focusing on chunky riffs and fiery guitar solos. In a mere three years, Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores the band sold 15 million records, played to SRO crowds throughout the U.S. and Europe, and one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Premiere Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Mardi Gras - The “Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar, heads to one of the biggest parties of the year, At Home and Social Mardi Gras. Join Sammy Hagar as he takes to the streets of New Orleans, checks out the Nuno Bettencourt & Friends - At Home and Social presents exclusive live performances, along world-famous floats, performs with Trombone Shorty, and hangs out with celebrity chef Emeril with intimate interviews, fun celebrity lifestyle pieces and insightful behind-the-scenes anec- Lagasse. dotes from our favorite music artists. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Premiere The Big Interview Special Edition 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Keith Urban - Dan catches up with country music superstar Keith Urban on his “Ripcord” tour. -

Wxw Holds Keynote on Wxw NOW Streaming

wXw holds keynote on wXw NOW streaming service, announces details on Germany's first wrestling network wXw just announced the first in-depth details on our new "wXw NOW" streaming network, which will launch one month from now on 8/13 at www.wxwnow.de. It will not just be a collection of shows like a lot of companies offer for a monthly fee via Pivotshare but also offer original content and a lot of archived shows, some dating back as far as 2006. We will also have our uniquely designed interface/UI, while hosting and infrastructure will be managed by Vimeo, our long-time streaming partner, dating back to 2013. Wrestling journalist Markus Gronemann (DarkMat.eu, Wrestling Observer) considers this to be the biggest launch of an over-the-top pro wrestling channel by a single promotion since New Japan World. wXw Managing Director Christian Jakobi held a keynote presentation tonight at 8 pm CEST at the wXw Wrestling Academy training school, which was streamed live on Facebook (the video is available, albeit only in German, here) and talked about what future and past events and what kind of original content would be available. We had up to 750 viewers simultaneously on Facebook and also had some students and a trainer (Toby Blunt) in attendance to provide some crowd noise and cheering at key points during the announcement. Marquee Events are wXw's version of pay-per-view caliber shows, where feuds start and end and international talent often appears. There currently are 10 marquee events on the calendar, with some of them being multi-day shows: -

Post-Gazette 8-10-12.Pmd

VOL. 116 - NO. 32 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, AUGUST 10, 2012 $.30 A COPY GREENWAY SPARKS CONTROVERSY OVER “TERRORIST” IMAGE by Sal Giarratani A debate has begun over a ored figures are iconic and by Julius Mourlon at the new mural in Dewey Square recurrent feature” in the Crono Festival in Lisbon not far from the Occupy work of these artistic sib- back in 2010. It is very simi- Boston site that depicts a lings and that “the figures lar to the Greenway mural large character peering out are frequently shown wear- except for the covering on from behind a red shirt ing whimsical hats, colorful the head and without a wrapped around the head. hoods or scarves — another crane positioned close to the Boston’s Fox 25 posted a hallmark feature of the art- character’s hand, leading photo of the 70 by 70 foot ists’ work.” me and many others to see mural on its Facebook page I viewed the photo and the it as an automatic weapon and within 24 hours had lots first thing I saw was a hooded that terrorists often use. of feedback. Most viewers of terrorist-looking character. Why wasn’t the crane re- the mural photo are under, If the purpose of this mural moved when the mural was what the Metro newspaper is to “bring color and energy completed? Many assume said was “the wrong impres- to the streets of Boston as that the crane was left there sion that the cartoon char- well as inspire curiosity and to add to the whole imagina- acter is wearing a Muslim imagination,” as the ICA tion thing. -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena Drawing ??? 1. NWA

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena drawing ??? 1. NWA U.S. Tag Champs The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) vs. The Rock-n-Roll Express. November 5, 1988 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? ($20,000) 1. The Sheepherders vs. ???. 2. Al Perez & Larry Zbyszko vs. Ron Simmons & The Italian Stallion. 3. Rick Steiner vs. Russian Assassin #2. 4. Bam Bam Bigelow & Jimmy Garvin vs. Mike Rotunda & Kevin Sullivan. 5. Ivan Koloff vs. Russian Assassin #1. 6. NWA U.S. Champ Barry Windham vs. Nikita Koloff. 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) Vs. The Fantastics (Fulton & Rogers). 8. Lex Luger beat NWA World Champ Ric Flair via DQ. February 22, 1989 in Centerville, OH Centerville High school drawing 600 1. Match results unavailable. April 24, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Shane Douglas beat Doug Gilbert. 2. The Great Muta beat George South. 3. The Samoan Swat Team beat Bob Emory & Mike Justice. 4. Ranger Ross beat The Iron Sheik. 5. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Mike Rotunda. 6. Ricky Steamboat & Lex Luger beat Ric Flair & Michael Hayes. Great American Bash 1989 July 21, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Brian Pillman beat Bill Irwin. 2. Sid Vicious & Dan Spivey beat Johnny & Davey Rich. 3. Norman beat Scott Casey. 4. Scott Steiner beat Mike Rotunda via DQ. 5. Steve Williams beat ???. 6. Sid Vicious and Dan Spivey won a “two ring battle royal.” 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) beat Rip Morgan & Jack Victory. 8. The Road Warriors beat The Samoan Swat Team. 9. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Norman. -

Symbol of Conquest, Alliance, and Hegemony

SYMBOL OF CONQUEST, ALLIANCE, AND HEGEMONY: THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS IN COLONIAL MEXICO by ZACHARY WINGERD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2008 Copyright © by Zachary Wingerd 2008 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I offer thanks to Dr. Dennis Reinhartz, Dr. Kenneth Philp, Dr. Richard Francaviglia, and Dr. Joseph Bastien who agreed to sit on my dissertation committee and guide my research and writing. Special thanks are given to Dr. Douglas Richmond who encouraged my topic from the very beginning and as the committee chair actively supported my endeavor. May 1, 2008 iii DEDICATED TO MY LOVING WIFE AND SONS Lindsey, Josh, and Jamie iv ABSTRACT SYMBOL OF CONQUEST, ALLIANCE, AND HEGEMONY: THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS IN COLONIAL MEXICO Zachary Wingerd, PhD. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Douglas Richmond The universality of the cross image within the transatlantic confrontation meant not only a hegemony of culture, but of symbolism. The symbol of the cross existed in both European and American societies hundreds of years before Columbus. In both cultures, the cross was integral in religious ceremony, priestly decoration, and cosmic maps. As a symbol of life and death, of human and divine suffering, of religious and political acquiescence, no other image in transatlantic history has held such a perennial, powerful message as the cross. For colonial Mexico, which felt the brunt of Spanish initiative, the symbol of the cross penetrated the autochthonous culture out of which the independent nation and indigenous church were born. -

Arena Puebla

Octubre 2020 Spanish Reader ARENA PUEBLA Arena Puebla lugar de diversión y tradición. Septiembre es uno de los meses más importantes para los mexicanos, no solo por las fiestas patrias sino también por el “Día Nacional de la Lucha Libre y del Luchador Profesional Mexicano'' que se celebra cada 21 de septiembre. Por esa razón es necesario hablar de la emblemática Arena Puebla, el lugar sagrado para los luchadores, el lugar en donde se desarrollan espectáculos tan emocionantes para los mexicanos. La Arena Puebla se fundó el 18 de julio de 1953, está ubicada en la 13 oriente 402 en el popular barrio El Carmen y tiene un espacio para 3000 aficionados. Fue inaugurada por Salvador Lutteroth González conocido como el padre de la lucha libre mexicana y quien fue el fundador del Consejo Mundial de la Lucha Libre (CMLL). Además, este espacio funciona como escuela de lucha libre, con más de 20 años de experiencia. Este año celebró 67 años de su creación, pero debido a la pandemia los festejos tuvieron que ser postergados. 01 Spanish Institute of Puebla www.sipuebla.com Octubre 2020 En su inauguración, la lucha estelar tuvo a grandes figuras como Black Shadow, Tarzán López, y Enrique Yañez, enfrentando al Verdugo, el Cavernario Galindo y el famosísimo Santo “El Enmascarado de Plata”, quien en aquel momento era el campeón mundial Welter. Diferentes luchadores han engalanado las noches en el cuadrilátero, entre ellos están Blue Demon, El Huracán Ramírez, Arturo Casco “La Fiera”, El Perro Aguayo, Semi- narista, Califa, Danger, El Hércules Poblano, Gorila Osorio, Petronio Limón, El Jabato, Manuel Robles, Furia Chicana, Gardenia Davis, El Faraón, Enrique Vera, Príncipe Rojo, Tarahumara, Chico Madrid, Gavilán, Sombra Poblana, Murciélago, El Santo Poblano, El Perro Aguayo Jr. -

PWTORCH NEWSLETTER • PAGE 2 Www

ISSUE #1255 - MAY 26, 2012 TOP FIVE STORIES OF THE WEEK PPV ROUNDTABLE (1) Raw expanding to three hours on July 23 (2) Impact going live every week this summer (3) Flair parting ways with TNA, WWE bound WWE OVER THE LIMIT (4) Raw going “interactive” with weekly voting Staff Scores & Reviews (5) Laurinaitis pins Cena after Show turns heel Pat McNeill, columnist (6.5): The main problem with WWE Over The Limit? The main event went over the limit of what we’ll accept from WWE. You can argue that there was no reason to book John Cena against John Laurinaitis on a pay-per-view, and you’d be right. RawHEA eDLxINpE AaNnALYdSsIS to thrhoeurse, a nhd uosuaullyr tsher e’Js eunoulgyh re2de3eming But on top of that, there was no reason to book content to make it worth the investment. But Cena versus Laurinaitis to go as long as any other three hours? Three hours of lousy content is By Wade Keller, editor major pay-per-view match. And there was no enough that next time viewers might just tune in reason for Cena to drag the match out. It didn’t fit If you follow an industry long enough, you’re for a just an hour instead of the usual two and the storyline. And it made John Cena look like a bound to see some bad decisions being made. certainly not commit to all three. Or they might chump. or like The Stinger, when Big Show turned Some are worse than others, but it’s rare when pick their segments, watching the predictably heel for the umpteenth time and cost him the you think you might be seeing the Worst newsmaking segments at the start of each hour match. -

The Ethics of Eating Animals in Tudor and Stuart Theaters

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS Rob Wakeman, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professors Theresa Coletti and Theodore B. Leinwand Department of English, University of Maryland A pressing challenge for the study of animal ethics in early modern literature is the very breadth of the category “animal,” which occludes the distinct ecological and economic roles of different species. Understanding the significance of deer to a hunter as distinct from the meaning of swine for a London pork vendor requires a historical investigation into humans’ ecological and cultural relationships with individual animals. For the constituents of England’s agricultural networks – shepherds, butchers, fishwives, eaters at tables high and low – animals matter differently. While recent scholarship on food and animal ethics often emphasizes ecological reciprocation, I insist that this mutualism is always out of balance, both across and within species lines. Focusing on drama by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and the anonymous authors of late medieval biblical plays, my research investigates how sixteenth-century theaters use food animals to mediate and negotiate the complexities of a changing meat economy. On the English stage, playwrights use food animals to impress the ethico-political implications of land enclosure, forest emparkment, the search for new fisheries, and air and water pollution from urban slaughterhouses and markets. Concurrent developments in animal husbandry and theatrical production in the period thus led to new ideas about emplacement, embodiment, and the ethics of interspecies interdependence. THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS by Rob Wakeman Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Advisory Committee: Professor Theresa Coletti, Co-Chair Professor Theodore B. -

Ecw One Night Stand 2005 Part 1

Ecw one night stand 2005 part 1 Watch the video «xsr07t_wwe-one-night-standpart-2_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. Watch the video «xsr67g_wwe-one-night- standpart-4_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. Watch the video «xsr4o9_wwe-one-night-standpart-3_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. ECW One Night Stand Vince Martinez. Loading. WWE RAW () - Eric Bischoff's ECW. Description ECW TV AD ECW One Night Stand commercial WWE RAW () - Eric. WWE RAW () - Eric Bischoff's ECW Funeral (Part 1) - Duration: WrestleParadise , ECW One Night Stand () was a professional wrestling pay-per-view (PPV) event produced 1 Production; 2 Background; 3 Event; 4 Results; 5 See also; 6 References; 7 External links promotion, that he would be part of the WWE invasion of One Night Stand, and that he would take SmackDown! volunteers with him. Гледай E.c.w. One Night Stand part1, видео качено от swat_omfg. Vbox7 – твоето любимо място за видео забавление! one-night-stand-full-movie-part adli mezmunu mp3 ve video formatinda yükleye biləcəyiniz ECW One Night Stand - OSW Review #3 free download. Watch ECW One Night Stand PPVSTREAMIN (HIGH QUALITY)WATCH FULL SHOWCLOUDTIME (HIGH QUALITY)WATCH FULL. Sport · The stars of Extreme Championship Wrestling reunite to celebrate the promotion's history Tommy Dreamer in ECW One Night Stand () Steve Austin and Yoshihiro Tajiri in ECW One Night Stand () · 19 photos | 1 video | 15 news articles». Long before WWE made Extreme Rules a part of its annual June ECW One Night Stand was certainly not a very heavily promoted. Turn on 1-Click ordering for this browser .