(1802-1834) Chapter 1 Harriet Martineau Grows up in Norwich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shepherd on the Hill: Comparative Notes on English and German Romantic Landscape Painting 1810-1831

The Shepherd on the Hill: Comparative Notes on English and German Romantic Landscape Painting 1810-1831. Conference paper Conference: ‘Romantic Correspondences’, The Centre for Regional Cultures, University of Nottingham and Nottingham Trent University, Newstead Abbey. Date: 4 November 2005 Abstract The solitary figure in the landscape can be understood in relation to certain, fundamentally Romantic traits – solitude, contemplation, oneness with nature – and is most notably found in the work of Caspar David Friedrich. Less recognised however is the fact that the solitary figure can also be found in the landscape paintings of many English artists of the early nineteenth century, particularly within depictions of commonly held pastoral landscapes. Within the traditional terms of English art history, the landscape genre of this period has also been closely associated with the concept of Romanticism. This paper will study the use of the solitary figure in paintings of open, common field landscape, and will compare two paintings: Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Landscape with Rainbow (The Shepherd’s Complaint)’ of 1810, and John Sell Cotman’s ‘The Shepherd on the Hill’ of 1831. It will examine the more conventional Romantic resonances of Friedrich’s painting in order to question whether Cotman’s shepherd is a comparative example of Romantic solitude and contemplation, or whether it was more of a prosaic image of a typically English ‘rustic type’ at a time when a particular sense of national identity was emerging that was closely associated with the countryside and country life. From there, it is hoped that we can begin to reconsider the conventional Romantic image of English landscape painting in the first three decades of the nineteenth century. -

The Norwich School John Old Crome John Sell Cotman George Vincent

T H E NO RW I CH SCH OOL JOH N “ OLD ” CROME JOH N SELL c o TMAN ( ) , G E OR G E ‘D I N C E N T JA ME A , S S T RK 1 B N Y C OM JOHN I T . E E E R R , TH R LE D BROOKE D A ’DI D H OD N R. LA , GSO ? J J 0 M. E . 0TM 89 . g/{N E TC . WITH ARTI LES BY M UND ALL C H . C P S A , . CONT ENTS U A P S A R I LES BY H M C ND LL . A T C . , Introduction John Crome John Sell Cotman O ther Members of the Norwich School I LLUSTRATIONS I N COLOURS l Cotman , John Sel Greta rid Yorkshire t - B ge, (wa er colour) Michel Mo nt St. Ruined Castle near a Stream B oats o n Cromer Beach (oil painting) Crome , John The Return ofthe Flock— Evening (oil painting) The Gate A athin Scene View on the Wensum at Thor e Norivtch B g p , (oil painting) Road with Pollards ILLUSTRAT IONS IN MONOTONE Cotman , John Joseph towards Norwich (water—colour) lx x vu Cotman , John Sell rid e Valle and Mountain B g , y, Llang ollen rid e at Sa/tram D evo nshire B g , D urham Castle and Cathedral Windmill in Lincolnshire D ieppe Po wis Cast/e ‘ he alai d an e t Lo T P s e Justic d the Ru S . e , Ro uen Statue o Charles I Chart/2 Cross f , g Cader I dris Eto n Colleg e Study B oys Fishing H o use m th e Place de la Pucelle at Rouen Chdteau at Fo ntame—le— en i near aen H r , C Mil/hank o n the Thames ILLUSTRATIONS IN MONOTONE— Continued PLATE M Cotman , iles Edmund Boats on the Medway (oil painting) lxxv Tro wse Mills lxxvi Crome , John Landscape View on th e Wensum ath near o w ch Mousehold He , N r i Moonlight on the Yare Lands cape : Grov' e Scene The Grove Scene Marlin o rd , gf The Villag e Glade Bach o the Ne w Mills Norwich f , Cottage near L ahenham Mill near Lahenham On th e Shirts of the Forest ive orwich Bach R r, N ru es Ri'ver Ostend in the D istance B g , ; Moo nlight Yarmouth H arho ur ddes I tal e s Parts 1 oulevar i n 1 8 . -

The Norwich School of Lithotomy

THE NORWICH SCHOOL OF LITHOTOMY by A. BATTY SHAW A NOTABLE cHAPTER in the long history of human bladder stone has been contributed from Norwich and its county of Norfolk and this came about for several reasons. The main reason was that Norfolk enjoyed the unenviable reputation during the latter part of the eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth centuries of having the highest incidence of bladder stone among its inhabitants of any county in Great Britain. As a result of thishigh prevalence ofbladderstone a local tradition of surgical skill in the art of lithotomy emerged and when the first general hospital in Norfolk, the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital was founded in 1771-2 there were appointed to its surgical staff local surgeons who were most experienced lithotomists. Their skill was passed on to those who followed them and earned for the hospital a European reputation for its standards of lithotomy. Sir Astley Cooper" when at the height of his professional fame and influence in 1835 spoke of these standards as follows, 'the degree of success which is considered most correct [for lithotomy] is that taken from the results of the cases at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital'.2 There were not only able lithotomists on the early staff of the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital but also physicians who wrote on the medical aspects of bladder stone with special reference to the problems of incidence and chemical analysis. These writings were based on the registers of admissions to the hospital which were kept from the hospital's inception. The keeping of a hospital register was an uncommon practice at the turn of the eighteenth century as is revealed by Alexander Marcet3 in a mono- graph on calculous disease of the urinary tract which he published in 1817. -

After the Norwich School

After the Norwich School This book takes, as its starting point, sites that feature in paintings, or prints, made by Norwich School artists. For each site I have photographed a contemporary landscape scene. My aim was not to try to replicate the scene painted in the 1800s, but simply to use that as the point where I would take the photograph, thus producing a picture of Norwich today. IMPORTANT This ebook has been produced as part of my studies with OCA for the landscape photography module of my Creative Arts degree course. It is not set to be published, but simply to allow my tutors, assessors and fellow students to see, judge and comment on my work. I am grateful that Norfolk Museums Service allow images to be downloaded for such educational use and I am pleased to credit © Norfolk Museums Service for each of the Norwich School painters images that I have used Robert Coe OCAStudent ID 507140 Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution View on the River Wensum After 'View on the River Wensum, King Street, Norwich' by John Thirtle (1777-1839), pencil and watercolour on paper, undated; 25.8 cm x 35.2 cm © Norfolk Museums Service Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Briton's Arms, Elm Hill After 'Briton's Arms' by Henry Ninham (1793-1874), watercolour on paper, © Norfolk Museums Service Proof Copy: Not optimised for high -

Norfolk Records Committee

NORFOLK RECORDS COMMITTEE Date: Friday 27 April 2012 Time: 10.30am Venue: The Green Room, The Archive Centre County Hall, Martineau Lane, Norwich Please Note: Arrangements have been made for committee members to park on the county hall front car park (upon production of the agenda to the car park attendant) provided space is available. Persons attending the meeting are requested to turn off mobile phones. Unidentified church in a landscape: a pencil drawing made by Elizabeth Fry, under the supervision of John Crome, 1808 (from Norfolk Record Office, MC 2784). Membership Mr J W Bracey Broadland District Council Substitute: Mrs B Rix Ms D Carlo Norwich City Council Mrs A Claussen-Reynolds North Norfolk District Council Mrs M Coleman Great Yarmouth Borough Council Mr P J Duigan Breckland District Council Substitute: Mrs S Matthews Mr G Jones Norfolk County Council Substitute: Mr J Joyce Dr C J Kemp South Norfolk District Council Substitute: Mr T Blowfield Mr D Murphy Norfolk County Council Substitute: Mrs J Leggett Mrs E A Nockolds King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council Mr M Sands Norwich City Council Ms V Thomas Norwich City Council Mr T Wright Norfolk County Council Substitute: Mrs J Leggett Non-Voting Members Mr M R Begley Co-opted Member Mr R Jewson Custos Rotulorum Dr G A Metters Representative of the Norfolk Record Society Dr V Morgan Observer Prof. C Rawcliffe Co-opted Member Revd C Read Representative of the Bishop of Norwich Prof. R Wilson Co-opted Member For further details and general enquiries about this Agenda please contact the Committee Officer: Kristen Jones on 01603 223053 or email [email protected] A g e n d a 1. -

Analysis, Conclusions, Recommendations & Appendices

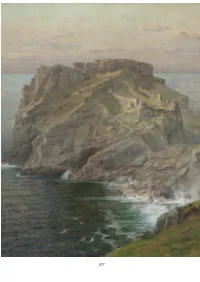

377 Chapter 5: Analysis of Results 378 CHAPTER 5 Analysis of Results 5.1. Introduction The coastal zones of England, Scotland and Wales are of enormous variety, scenic beauty and geomorphological interest on account of the wide range of geological exposures to be observed. The geological history, including the impacts of mountain building phases, have caused the rocks to be compressed, folded and faulted and, subsequently, they have been subjected to the processes of weathering and erosion over millions of years. Later, the impacts of glaciation and changes in sea level have led to the evolution and shaping of the coastline as we know it today. Over the last two centuries geologists, geographers and archaeologists have provided evidence of coastal change; this includes records of lost villages, coastal structures such as lighthouses, fortifications and churches, other important archaeological sites, as well as natural habitats. Some of these important assets have been lost or obscured through sea level rise or coastal erosion, whilst elsewhere, sea ports have been stranded from the coast following the accretion of extensive mudflats and saltmarshes. This ‘State of the British Coast’ study has sought to advance our understanding of the scale and rate of change affecting the physical, environmental and cultural heritage of coastal zones using artworks dating back to the 1770s. All those involved in coastal management have a requirement for high quality data and information including a thorough understanding of the physical processes at work around our coastlines. An appreciation of the impacts of past and potential evolutionary processes is fundamental if we are to understand and manage our coastlines in the most effective and sustainable way. -

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers Palmers Lane Aylsham East Anglian Sale Norwich NR11 6JA United Kingdom Started 28 Oct 2016 10:30 BST

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers Palmers Lane Aylsham East Anglian Sale Norwich NR11 6JA United Kingdom Started 28 Oct 2016 10:30 BST Lot Description HENRY NINHAM (1793-1874, BRITISH) Tree study; Fishing Scene (2) and North Denes, Yarmouth group of four black and white 1 etchings assorted sizes, all mounted but unframed (4) MILES EDMUND COTMAN (1810-1858, BRITISH) "At Surlingham" black and white etching published circa 1846 2 x 7 ins, mounted but 2 unframed JOSEPH STANNARD (1797-1830, BRITISH) "Thatched cottage with a gable end" black and white etching published circa 1824 6 x 8 3 ins, mounted but unframed MILES EDMUND COTMAN (1810-1858, BRITISH) "Lane Scene" black and white etching 6 1/4 x 5 1/4 ins, mounted but unframed (A/F) 4 together with two further Norwich School etchings/engravings (3) AFTER J M W TURNER ENGRAVED BY W MILLER "Great Yarmouth, Norfolk" 19 century hand coloured engraving 7 x 9 ins together 5 with six further engravings relating to Great Yarmouth and Gorleston (7) HOLMES CORNELIUS WINTER (1851-1935, BRITISH) Old Street, Great Yarmouth March 1863 coloured etching, signed and inscribed 6 "Copy No 5" in ink to lower margin 12 x 10 ins AFTER POWLES ENGRAVED BY J COOK "A perspective view of Lowestoft from the N E Battery black and white engraving published 7 by J Harris circa 1790 9 1/2 x 20 ins AFTER J STARK ENGRAVED BY J HORSBURGH "St Benedict's Abbey" hand coloured engraving published by Moon 1833 together 8 with eight further hand coloured engravings of Norfolk views assorted sizes (9) JOHN SELL COTMAN (1782-1842, BRITISH) -

Download Walking Crome's Norwich: a Self-Guided Trail of Crome's City

WALKING CROME’S A self-guided trail NORWICH of Crome’s city About the Walk John Crome lived and worked in Norwich all his life. From humble beginnings he became a drawing master and was one of the principal founders of the Norwich Society of Artists. He remains one of the country’s great Romantic painters, rooting his work in the local landscape. During the first lockdown of 2020, local photographer Nick Stone followed in Crome’s footsteps, walking the deserted city streets exploring Crome’s Norwich and pinpointing the painter’s locations and capturing them with a fresh eye. This walk takes you to places Crome would have known and visits some of the locations he painted. About John Crome John Crome was born in 1768 in The Griffin pub close to Norwich Cathedral. The son of a weaver, born at a time when the city was at the centre of an important international trade in textiles. In the 1780s over thirty different trades associated with textiles were located in the noisy and colourful area known as ‘Norwich Over the Water’, north of the River Wensum. The river formed the artery for the textile industry, and the warehouses, dyers’ premises and quays were well known to Crome and featured frequently in his works. Norwich at the time was known for radical politics, and inns and taverns in the city were home to societies and clubs where ideas were shared, and debates were held. The Rifleman pub hosted ‘The Dirty Shirt Club’ where men could go in working clothes, to drink, smoke and socialise. -

'This Made Me a Painter!'

‘THIS MADE ME A PAINTER!’ J.M.W. Turner and the perception of Holland and Dutch art in Romantic Britain Quirine van der Meer Mohr RMA Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context Utrecht University Prof. Dr. Peter Hecht 1 THIS MADE ME A PAINTER’. J.M.W. Turner and the perception of Holland and Dutch art in Romantic Britain Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1 Beautiful, Sublime and Picturesque 11 The reception of Dutch Art in Romantic Britain Chapter 2 Waterways and neat cities 25 Holland through the eyes of the British traveller Chapter 3 ‘Quite a Cuyp’ 36 Turner in Holland Chapter 4 The ‘Dutchness’ of Turner’s art 56 A reflection of the artistic results of Turner’s Dutch journeys Chapter 5 Made in Holland 82 English artists painting Holland Conclusion 100 Bibliography 104 List of Resources 109 List of Images 110 2 Introduction In 1842, the British painter Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) exhibited a painting at London’s Royal Academy that went beyond everyone’s imagination. Exploring the effects of an elemental vortex, Snow Storm - Steam Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (Tate), shows a swift suggestion of a steam-ferry in the heart of the composition. The vessel is heavily suffering under the rough weather conditions of a snowstorm at sea, which, by an eruption of swirls of paint onto the canvas, denies the viewer the possibility to fully survey the entire episode. Instead, the viewer is swept away into the vortex, leaving him nothing else but the terrifying sensation of mankind’s futility opposed to the tempestuous forces of nature. -

The Norfolk Ancestor

CoverJun 18.qxp_NorfolkAncestor CoverJun15.qxd 30/04/2018 16:35 Page 1 Then and Now The Norfolk Ancestor JUNE 2018 These two pictures show the junction between Newmarket Road on the right and Ipswich Road on the left outside the old Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. The top one dates from 1876 and the bottom one from 2018. In the 1876 picture you can see the famous Boileau Fountain which sadly is no longer there. To read about the story of the fountain turn to the inside back cover. The Journal of the Norfolk Family History Society formerly Norfolk & Norwich Genealogical Society CoverJun 18.qxp_NorfolkAncestor CoverJun15.qxd 30/04/2018 16:35 Page 3 The Boileau Fountain A Brush with History A few weeks ago a kind lady, Mrs Annetta EVANS, NORWICH and the surrounding area has a long standing association with the handed me a series of photographs of Norfolk and brush making industry with towns like Wymondham and Attleborough becoming Norwich that she had taken over the years and asked important manufacturing centres over the years. Brushes had been made in me if they would be of any interest to the NFHS. Norwich from the eighteenth century and by 1890 there were at least 15 brush When I looked through them, a number of them trig- making firms in the city. gered ideas for articles. The picture on the right was taken in the grounds of the old Norfolk and Norwich One of the most important stories centres Hospital which stands on Newmarket Road. It shows around Samuel DEYNS. -

ENGLISH LANDSCAPE ARTISTS Drawings and Prints Prints and Drawings Galleries/June 26-September 6,1971

ENGLISH LANDSCAPE ARTISTS Drawings and Prints Prints and Drawings Galleries/June 26-September 6,1971 r,«> V ' ^JKtA^fmrf .^r*^{. v! •,\ ^ ^fc-^i I- 0 It has long been recognised that there is a special affinity between the English people and landscape. As painters and sketchers of landscape, as lyrical nature poets, and as landscape gardeners (of the Nature-Arranged school as distinct from the formal continental embroidery-parterre style) the XVIIIth and early XlXth century English outstripped everyone else. Moved by more than just the romantic spirit of the times, the English, although fascinated by impassioned anthropomor phic renderings of storms, also enjoyed serene pictures of the familiar out-of-doors. Starting at least as far back as the XVIIth century with a topographical interest, portraits of their own homes and countryside have always appealed to the English, the way color snapshots of favorite places still do. The people who could afford to have painters and engravers make bird's-eye views of their house and grounds in the XVIIth century were also travelling on the continent, looking at the Roman campagna and collecting both paintings and drawings of it to take home. By the XVIIIth century, having trained their eyes to accept and even enjoy drawings, English gentlemen hired drawing masters to teach their children how to "take a landskip". Many a drawing master and even well-known painters, finding that they needed to supplement meagre incomes, wrote and illustrated books of instruction. While a few drawing books were produced elsewhere, they were mainly devoted to figure drawing, but the English (and also the American) ones were extremely nu merous, and almost entirely devoted to landscape. -

Transactions 1899

/ r TRANSACTIONS OF THK NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY. [Edited bt W. A. NICHOLSON, Hon. Sec.] — The Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society has for its objects; 1. The Practical Study of Natural Science. 2. The protection, by its influence with landowners and others, of indigenous species requiring protection, and the circulation of information which may dispel prejudices leading to their destruction. 3. The discouragement of the practice of destroying the rarer species of birds that occasionally visit the County, and of exterminating rare plants in their native localities. 4. The record of facts and traditions connected with the habits, distribution, and former abundance or otherwise of animals and plants which have become extinct in the County; and the use of all legitimate means to prevent the extermination of existing species, more especially those known to be diminishing in numbers. 5 . The publication of Papers on Natural History, contributed to the Society, especially such as relate to the County of Norfolk. 6. The facilitating a friendly intercourse between local Naturalists, by means of Meetings for the reading and discussion of papers and for the exhibition of specimens, supplemented by Field-meetings and Excursions, with a view to extend the study of Natural Science on a sound and systematic basis. : TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK AND NORWICH VOL. VII. 1899—1900 to 1903— 4 . £orfoicf) PRINTED BY FLETCHER AND SON, LTD. 1904. Errata. Page 19, third line, second paragraph, for “florine” read fluorine. ” Page 24, first line, fourth paragraph, for “ crystal read crystals. “ ” Page 83, seventh line from bottom, for wasteria read wistaria. ” Page 88, eleventh line from top, for “ Aronia read Aromia.