Gangs, Pagad & the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013

City of Cape Town – 2011 Census - Cape Flats Planning District August 2013 Compiled by Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS), City of Cape Town 2011 Census data supplied by Statistics South Africa (Based on information available at the time of compilation as released by Statistics South Africa) Overview, Demographic Profile, Economic Profile, Dwelling Profile, Household Services Profile Planning District Description The Cape Flats Planning District is located in the southern part of the City of Cape Town and covers approximately 13 200 ha. It is bounded by the M5 in the west, N2 freeway to the north, Lansdowne Road and Weltevreden Road in the east and the False Bay coastline to the south. 1 Data Notes: The following databases from Statistics South Africa (SSA) software were used to extract the data for the profiles: Demographic Profile – Descriptive and Education databases Economic Profile – Labour Force and Head of Household databases Dwelling Profile – Dwellings database Household Services Profile – Household Services database Planning District Overview - 2011 Census Change 2001 to 2011 Cape Flats Planning District 2001 2011 Number % Population 509 162 583 380 74 218 14.6% Households 119 483 146 243 26 760 22.4% Average Household Size 4.26 3.99 In 2011 the population of Cape Flats Planning District was 583 380 an increase of 15% since 2001, and the number of households was 146 243, an increase of 22% since 2001. The average household size has declined from 4.26 to 3.99 in the 10 years. A household is defined as a group of persons who live together, and provide themselves jointly with food or other essentials for living, or a single person who lives alone (Statistics South Africa). -

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR the Scorpions and the Politics of Justice

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR The Scorpions and the politics of justice David Bruce Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation [email protected] In May 2008 legislation was tabled in Parliament providing for the dissolution of the Directorate of Special Operations (known as the ‘Scorpions’), an investigative unit based in the National Prosecuting Authority. The draft legislation provides that Scorpions members will selectively be incorporated into a new investigative unit located within the SAPS. These developments followed a resolution passed at the African National Congress National Conference in Polokwane in December 2007, calling for the unit to be disbanded. Since December the ANC has been forced to defend its decision in the face of widespread support for the Scorpions. One of the accusations made by the ANC was that the Scorpions were involved in politically motivated targeting of ANC members. This article examines the issue of political manipulation of criminal investigations and argues that doing away with the Scorpions will in fact increase the potential for such manipulation thereby undermining the principle of equality before the law. he origins of current initiatives to do away Accordingly we have decided not to with the Scorpions go back several years. In prosecute the deputy president (Mail and T2001 the National Prosecuting Authority Guardian online 2003). (NPA) approved an investigation into allegations of corruption in the awarding of arms deal contracts. Political commentator, Aubrey Matshiqi has argued In October 2002 they announced that this probe that this statement by Ngcuka ‘has in some ways would be extended to include allegations of bribery overshadowed every action taken in relation to against Jacob Zuma, then South Africa’s deputy Zuma by the NPA since that point.’ Until June president. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

1 Additional Analysis on SAPS Resourcing for Khayelitsha

1 Additional analysis on SAPS resourcing for Khayelitsha Commission Jean Redpath 29 January 2014 1. I have perused a document labelled A3.39.1 purports to show the “granted” SAPS Resource Allocation Guides (RAGS) for 2009-2011 in respect of personnel, vehicles and computers, for the police stations of Camps Bay, Durbanville, Grassy Park, Kensington, Mitchells Plain, Muizenberg, Nyanga, Philippi and Sea Point . For 2012 the document provides data on personnel only for the same police stations. 2. I am informed that RAGS are determined by SAPS at National Level and are broadly based on population figures and crime rates. I am also informed that provincial commissioners frequently make their own resource allocations, which may be different from RAGS, based on their own information or perceptions. 3. I have perused General Tshabalala’s Task Team report which details the allocations of vehicles and personnel to the three police stations of Harare, Khayelitsha and Lingelethu West in 2012. It is unclear whether these are RAGS figures or actual figures. I have combined these figures with the RAGS figures in the document labelled A3.39.1 in the tables below. 4. I have perused documents annexed to a letter from Major General Jephta dated 13 Mary 2013 (Jephta’s letter). The first annexed document purports to show the total population in each police station for all police stations in the Western Cape (SAPS estimates). 5. Because the borders of Census enumerator areas do not coincide exactly with the borders of policing areas there may be slight discrepancies between different estimates of population size in policing areas. -

Kurosawa's Hamlet?

Kurosawa’s Hamlet? KAORI ASHIZU In recent years it has suddenly been taken for granted that The Bad Sleep Well (Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemuru, 1960) should be includ- ed with Kumonosujô and Ran as one of the films which Akira Kuro- sawa, as Robert Hapgood puts it, “based on Shakespeare” (234). However, although several critics have now discussed parallels, echoes and inversions of Hamlet, none has offered any sufficiently coherent, detailed account of the film in its own terms, and the exist- ing accounts contain serious errors and inconsistencies. My own in- tention is not to quarrel with critics to whom I am in other ways in- debted, but to direct attention to a curious and critically alarming situation. I For example, we cannot profitably compare this film with Hamlet, or compare Nishi—Kurosawa’s “Hamlet,” superbly played by Toshirô Mifune—with Shakespeare’s prince, unless we understand Nishi’s attitude to his revenge in two crucial scenes. Yet here even Donald Richie is confused and contradictory. Richie first observes of the earlier scene that Nishi’s love for his wife makes him abandon his revenge: “she, too, is responsible since Mifune, in love, finally de- cides to give up revenge for her sake, and in token of this, brings her a [ 71 ] 72 KAORI ASHIZU bouquet . .” (142).1 Three pages later, he comments on the same scene that Nishi gives up his plan to kill those responsible for his father’s death, but determines to send them to jail instead: The same things may happen (Mori exposed, the triumph of jus- tice) but the manner, the how will be different. -

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW

INTEGRATED HUMAN SETTLEMENTS FIVE-YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN July 2012 – June 2017 2013/14 REVIEW THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN’S VISION & MISSION The vision and mission of the City of Cape Town is threefold: • To be an opportunity city that creates an enabling environment for economic growth and job creation • To deliver quality services to all residents • To serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and corruption-free administration The City of Cape Town pursues a multi-pronged vision to: • be a prosperous city that creates an enabling and inclusive environment for shared economic growth and development; • achieve effective and equitable service delivery; and • serve the citizens of Cape Town as a well-governed and effectively run administration. In striving to achieve this vision, the City’s mission is to: • contribute actively to the development of its environmental, human and social capital; • offer high-quality services to all who live in, do business in, or visit Cape Town as tourists; and • be known for its efficient, effective and caring government. Spearheading this resolve is a focus on infrastructure investment and maintenance to provide a sustainable drive for economic growth and development, greater economic freedom, and increased opportunities for investment and job creation. To achieve its vision, the City of Cape Town will build on the strategic focus areas it has identified as the cornerstones of a successful and thriving city, and which form the foundation of its Five-year Integrated Development Plan. The vision is built on five key pillars: THE OPPORTUNITY CITY Pillar 1: Ensure that Cape Town continues to grow as an opportunity city THE SAFE CITY Pillar 2: Make Cape Town an increasingly safe city THE CARING CITY Pillar 3: Make Cape Town even more of a caring city THE INCLUSIVE CITY Pillar 4: Ensure that Cape Town is an inclusive city THE WELL-RUN CITY Pillar 5: Make sure Cape Town continues to be a well-run city These five focus areas inform all the City’s plans and policies. -

Undamaged Reputations?

UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF VIOLENCE AND RECONCILIATION Criminal Justice Programme October 2007 UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Supported by Irish Aid ABOUT THE AUTHOR Aubrey Matshiqi is an independent researcher and currently a research associate at the Centre for Policy Studies. Published by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation For information contact: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 4th Floor, Braamfontein Centre 23 Jorissen Street, Braamfontein PO Box 30778, Braamfontein, 2017 Tel: +27 (11) 403-5650 Fax: +27 (11) 339-6785 http://www.csvr.org.za © 2007 Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. All rights reserved. Design and layout: Lomin Saayman CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 1. Introduction 5 2. The nature of the conflict in the ANC and the tripartite alliance 6 3. The media as a role-player in the crisis 8 4. The Zuma saga and the criminal justice system 10 4.1 The NPA and Ngcuka’s prima facie evidence statement 10 4.2 The judiciary and the Shaik judgment 11 5. The Constitution and the rule of law 12 6. Transformation of the judiciary 14 7. The appointment of judges 15 8. The right to a fair trial 17 9. Public confidence in the criminal justice system 18 10. -

Living History – the Story of Adderley Street's Flower

LIVING HISTORY – THE STORY OF ADDERLEY STREET’S FLOWER SELLERS Lizette Rabe Department of Journalism, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7602 Lewende geskiedenis – die verhaal van Adderleystraat se blommeverkopers Kaapstad is waarskynlik sinoniem met Tafelberg. Maar een van die letterlik kleurryke tonele aan die voet van dié berg is waarskynlik eweneens sinoniem met die stad: Adderleystraat se “beroemde” blommeverkopers. Tog word hulle al minder, hoewel hulle deel van Kaapstad se lewende geskiedenis is en letterlik tot die Moederstad se kleurryke lewe bygedra het en ’n toerismebaken is. Waar kom hulle vandaan, en belangrik, wat is hulle toekoms? Dié beskrywende artikel binne die paradigma van mikrogeskiedenis is sover bekend ’n eerste sosiaal-wetenskaplike verkenning van die geskiedenis van dié unieke groep Kapenaars, die oorsprong van die blommemark en sy kleurryke blommenalatenskap. Sleutelwoorde: Adderleystraat; blommemark; blommeverkopers; Kaapstad; kultuurgeskiedenis; snyblomme; toerisme; veldblomme. Cape Town is probably synonymous with Table Mountain. But one of the colourful scenes at the foot of the mountain may also be described as synonymous with the city: Adderley Street’s “famous” fl ower market. Yet, although the fl ower sellers are part of Cape Town’s living history, a beacon for tourists, and literally contributes to the Mother City’s vibrant and colourful life, they represent a dying breed. Where do they come from, and more importantly, what is their future? This descriptive article within the paradigm of microhistory is, thus far known, a fi rst social scientifi c exploration of the history of this unique group of Capetonians, the origins of the fl ower market, and its fl ower legacy. -

KTC Informal Settlement Pocket

Enumeration Report KTC Informal Settlement Pocket MARCH 2017 A member of the SA SDI Alliance Enumeration Report: KTC Informal Settlement Pocket CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES 3 LIST OF FIGURES 3 LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 4 GLOSSARY 4 PREFACE 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 1. INTRODUCTION 8 2. LOCATION AND CONTEXT OF THE SETTLEMENT 11 3. METHODOLOGY 14 3.1. Stakeholder participation and engagement 14 3.2. Pre-implementation and field work 15 3.3. Value add to the project – employment opportunities 16 4. COVERAGE OF THE ENUMERATION AND RESPONSE RATES 17 4.1. Coverage of the enumeration 17 4.2. Response rates 20 5. SUMMARY FINDINGS 21 6. ANALYSIS 22 6.1. Structure analysis 22 6.2. Demographics of KTC population 28 6.2.1. Age distribution 28 6.2.1.1 A profile of youth 29 6.2.2. Gender breakdown 30 6.2.3. Education enrolment and school attendance 31 6.2.4. Employment 32 6.2.5. Household income and expenditure 37 6.3. Access to services 40 6.3.1. Water access 41 6.3.2. Sanitation 43 6.3.3. Electricity 45 6.3.4. Community services and local business 47 6.4. Health and disasters 49 6.5. Settlement dynamics 49 6.6. Settlement priorities 50 6.7. Implications of findings for human settlements 53 6.7.1. Planning considerations 53 6.7.2. Pathway to qualification 54 7. CONCLUSION 60 REFERENCES 61 LIST OF CORE TEAM MEMBERS 62 2 Enumeration Report: KTC Informal Settlement Pocket LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Total population of KTC derived from stated number of people living inside each structure 19 Table 2: Total population of KTC based on actual number of persons -

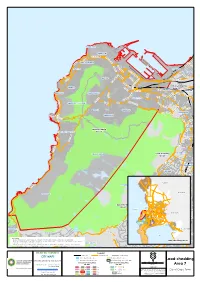

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis.