01 Station During the War Years the Central Station in Arnhem Was Made Use of in Various Ways and Stood As a Symbol for a Number of Incidents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEPT Study Tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019

Facilitating Electric Vehicle Uptake LEPT study tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019 1 Background Organising the study tour The London European Partnership for Transport (LEPT) has sat within the London Councils Transport and Mobility team since 2006. LEPT’s function is to coordinate, disseminate and help promote the sustainable transport and mobility agenda for London and London boroughs in Europe. LEPT works with the 33 London boroughs and TfL to build upon European knowledge and best practice, helping cities to work together to deliver specific transport policies and initiatives, and providing better value to London. In the context of a wider strategy to deliver cleaner air and reduce the impact of road transport on Londoners’ health, one of London Councils’ pledges to Londoners is the upscaling of infrastructures dedicated to electric vehicles (EVs), to facili- tate their uptake. As part of its mission to support boroughs in delivering this pledge and the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, LEPT organised a study tour in May 2019 to allow borough officers to travel to the Netherlands to understand the factors that led the country’s cities to be among the world leaders in providing EV infrastructure. Eight funded positions were available for borough officers working on electric vehicles to join. Representatives from seven boroughs and one sub-regional partnership joined the tour as well as two officers from LEPT and an officer that worked closely on EV charging infrastructure from the London Councils Transport Policy team (Appendix 1). London boroughs London’s air pollution is shortening lives and improving air quality in the city is a priority for the London boroughs. -

Generaal Urquhartlaan 4 6861 GG Oosterbeek

Generaal Urquhartlaan 4 6861 GG Oosterbeek Postbus 9100 6860 HA Oosterbeek Telefoon (026) 33 48 111 Fax (026) 33 48 310 Aan de leden van de gemeenteraad van Renkum Internet www.renkum.nl IBAN NL02BNGH0285007076 KvK 09215649 Datum Onderwerp 2 maart 2021 Inventarisatie ontmoeting Beste leden van de raad, voorzitter, Aanleiding Tijdens de commissievergadering van 9 februari is door Gemeentebelangen gevraagd naar de uitkomsten van de inventarisatie wat de verbindingen zijn in de verschillende dorpen om zo de cohesie te verbeteren. Beleidsvisie In de Kadernota Sociaal Domein 2019 is opgenomen dat wij inzetten op meer nabij, preventief, dorpsgericht en integraal. Daarbij is het belangrijk dat we per dorp/kern een stevig netwerk creëren met onze partners, voldoende algemene voorzieningen organiseren voor dat wat binnen de dorpen speelt en een model ontwikkelen waarmee we ingezette zorg/hulp eenvoudig en snel op en af kunnen schalen. Deze werkwijze is de rode draad van de ondersteuning die wij onze inwoners willen geven die zij nodig hebben, tegen de kosten die we kunnen financieren. De sociale basis bestaat uit wat inwoners zelf kunnen en wat zij samen met en voor elkaar doen. Dit varieert van burenhulp tot allerlei vrijwilligersinitiatieven, zoals hulp bij het invullen van formulieren of kleine klussen in- en rondom het huis. Wanneer we spreken over de inwoner en zijn eigen netwerk, dan is dit in Renkum relatief kansrijk. Veel mensen in onze gemeente bereid zijn iets voor een ander te doen en dat schept kansen. Ook helpt een sterke sociale basis professionals om inwoners goed te verbinden aan netwerken, activiteiten en algemene voorzieningen in de buurt. -

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region And

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region Together with the Province of Gelderland and the AER, ERRIN Members Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region are organising a study visit on the energy transition in Gelderland (NL) to share and learn from each other’s experiences. Originally, the study visit was planned for October 31st-November 2nd 2017 but has now been rescheduled for April 17-19 2018. All ERRIN members are invited to participate and can find the new programme and registration form online. In order to ensure that as many regions benefit as possible, we kindly ask that delegations are limited to a maximum of 3 persons per region since there is a maximum of 20 spots available for the whole visit. Multistakeholder collaboration The main focus of the study visit, which will be organised in cooperation with other interregional networks, will be the Gelders’ Energy agreement (GEA). This collaboration between local and regional industries, governments and NGOs’ in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands, has pledged for the province to become energy-neutral by 2050. It facilitates a co-creative process where initiatives, actors, and energy are integrated into society. a A bottom-up approach The unique nature of the GEA resides in its origin. The initiative sprouted from society when it faced the complex, intricate problems of the energy transition. The three initiators were GNMF, the Gelders’ environmental protection association, het Klimaatverbond, a national climate association and Alliander, an energy network company. While the provincial government endorses the project, it is not a top-down initiative. -

Het Heelsumse Beekdal

Het Heelsumse beekdal Drie beken De oorspronkelijke bronbeek in het Heelsumse beekdal werd eeuwenlang ver- graven of vervangen door sprengenbeken en diende als krachtbron voor de di- verse watermolens. Tot ver op de stuwwal werden sprengen gegraven, om gega- randeerd te zijn van een permanente wateraanvoer. Door het dal lopen drie beken: de Papiermolenbeek, de Wolfhezerbeek en de Heelsumse beek. De sprengen van de Papiermolenbeek liggen op de grootste afstand van de monding (circa 7 km). De sprengen liggen meters diep ingegraven in de stuwwal van Arnhem. Deze bovenloop staat vaak droog door de verlaging van het grond- waterpeil en gebrek aan onderhoud. Delen van de Papiermolenbeek zijn aange- takt aan de Wolfhezerbeek of zijn verdwenen. Tussen de Kabeljauw en papierfa- briek Schut is de beek als middenbeek weer in zicht. De Wolfhezerbeek heeft z’n uitgebreide sprengenstelsel bij de Wodanseiken en een tak ten noorden van het Kousenhuisje. Tot aan de Kabeljauw is de beekbed- ding nog grotendeels intact, maar daarna is ze goeddeels verdwenen. In de om- geving van het Rondeel (zie verderop in dit artikel) ligt een wirwar van geultjes. Deels sprengen, deels vergravingen om water bij het Rondeel te krijgen, maar ook oude wildkeringen met de bijbehorende geulen. De Heelsumse beek ontspringt op de Wolfhezer heide. Deze beek voert perma- nent water en is na de Kabeljauw opgeleid tot aan papierfabriek Schut. Hier stond vroeger papiermolen “de Veentjes”. Behoud van het gehele bekenstelsel in het Heelsumse beekdal is uitgangpunt voor het onderhoud door Waterschap Vallei & Eem (WVE) en Natuurmonumen- ten. Bij de A50 lopen de beken door betonnen goten en door duikers onder de Utrechtseweg en de A 50 door, komen bij elkaar en lopen als één beek door het dal verder naar de N225 (Wageningen-Oosterbeek). -

ISO 9001 Certificate

CERTIFICATE Number: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum belonging to: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway including the implementation meets the requirements of the standard: ISO 9001:2015 Scope: - Ship classification and statutory services for seagoing and inland waterway vessels - Offshore classification and statutory services - Maritime advisory services - Product certification Certificate expiry date: 28 December 2023 Certificate effective date: 11 March 2021 Certified since*: 1 November 2013 This certificate is valid for the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum. DEKRA Certification B.V. j E B.T.M. Holtus R.C. Verhagen Managing Director Certification Manager © Integral publication of this certificate and adjoining reports is allowed * against this certifiable standard / possibly by another certification body DEKRA Certification B.V. Meander 1051, 6825 MJ Arnhem P.O. Box 5185, 6802 ED Arnhem, The Netherlands T +31 88 96 83000 F +31 88 96 83100 www.dekra-certification.nl Company registration 09085396 page 1 of 13 ADDENDUM To certificate: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations of: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway Certified organizations and locations: DNV GL Angola Serviços Limitada DNV GL Argentina S.A Belas Business Park, Etapa V, Avenida Leandro N. Alem 790, 9th andar, Torre Cuanza Sul, Piso 6 – CABA, Talatona, Luanda Buenos Aires - C1001AAP Angola Argentina DNV GL Australia Pty -

WESTERTERP CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Klaas R Westerterp Education MSc Biology, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971. Thesis: The energy budget of the nestling Starling Sturnus vulgaris: a field study. Ardea 61: 127-158, 1973. PhD University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1976. Thesis: How rats economize – energy loss in starvation. Physiol Zool 50: 331-362, 1977. Professional employment record 1966-1971 Teaching assistant, Animal physiology, University of Groningen 1968-1971 Research assistant, Institute for Ecological Research, Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1971 Lecturer, Department of Animal Physiology, University of Groningen 1976 Lecturer, Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen 1977 Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Stirling, Scotland 1980 Postdoc, Animal Ecology, University of Groningen and Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1982 Senior lecturer, Department of Human Biology, Maastricht University 1998 Visiting professor, KU Leuven, Belgium 2001 Professor of Human Energetics, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University Research The focus of my work is on physical activity and body weight regulation, where physical activity is measured with accelerometers for body movement registration and as physical activity energy expenditure, under confined conditions in a respiration chamber and free-living with the doubly labelled water method. Management, advisory and editorial board functions Head of the department of Human Biology (1999-2005); PhD dean faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (2007- 2011); member of the FAO/WHO/UNU expert group on human energy requirements (2001); advisor Philips Research (2006-2011); advisor Medtronic (2006-2007); editor in chief Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2009-2012); editor in chief European Journal of Applied Physiology (2012-present). -

Route Arnhem

Route Arnhem Our office is located in the Rhine Tower From Apeldoorn/Zwolle via the A50 (Rijntoren), commonly referred to as the • Follow the A50 in the direction of Nieuwe Stationsstraat 10 blue tower, which, together with the Arnhem. 6811 KS Arnhem (green) Park Tower, forms part of Arnhem • Leave the A50 via at exit 20 (Arnhem T +31 26 368 75 20 Central Station. Center). • Follow the signs ‘Arnhem-Center’ By car and the route via the Apeldoornseweg as described above. Parking in P-Central Address parking garage: From Nijmegen via the A325 Willemstunnel 1, 6811 KZ Arnhem. • Follow the A325 past Gelredome stadium From the parking garage, take the elevator in the direction of Arnhem Center. ‘Kantoren’ (Offices). Then follow the signs • Cross the John Frost Bridge and follow ‘WTC’ to the blue tower. Our office is on the the signs ‘Centrumring +P Station’, When you use a navigation 11th floor. which is the road straight on. system, navigate on • After about 2 km enter the tunnel. ‘Willemstunnel 1’, which will From The Hague/ Utrecht (=Den Bosch/ The entrance of parking garage P-Central lead you to the entrance of Eindhoven) via the A12 is in the tunnel, on your right Parking Garage Central. • Follow the A12 in the direction of Arnhem. By public transport • Leave the A12 at exit 26 (Arnhem North). Trains and busses stop right in front of Via the Apeldoornseweg you enter the building. From the train or bus Arnhem. platform, go to the station hall first. From • In the built-up area, you go straight down there, take the escalator up and then turn the road, direction Center, past the right, towards exit Nieuwe Stationsstraat. -

SAH/ACF Program 2018

AIRBORNE HERDENKINGEN 2019 AIRBORNE COMMEMORATIONS 2019 PROGRAMMAVOORLOPIGE UITGAVEPROGRAMME PROVISIONAL EDITION MAANDAG 16 SEPTEMBER 2019 MONDAY SEPTEMBER 16, 2019 12.30 uur Opening 17e Airborne International Youth Conference/ 12.30 hrs Opening 17th Airborne International Youth Conference/ YOUCEE. Thema: nnb. Informatie: 06 22 46 12 67 YOUCEE. Theme: to be decided. Info: +31(0)6 22 46 12 67 DINSDAG 17 SEPTEMBER 2019 TUESDAY SEPTEMBER 17, 2019 09.00 uur Kranslegging Airborne Monument de Naald 09.00 hrs Wreath-laying Airborne Monument The Needle, Oosterbeek, Oosterbeek, Gemeente Renkum. Informatie: 026 3348111 Municipality of Renkum. Information: +31(0)26 3348111 19.00 uur Kranslegging Airborne Monument Bennekomseweg, 19.00 hrs Wreath-laying Airborne Monument Bennekomseweg, Heelsum. Informatie: www.oranjedagheelsum.nl Heelsum. Information: www.oranjedagheelsum.nl VRIJDAG 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 20, 2019 09.30 uur Bloemlegging. Monument provincie Gelderland 09.30 hrs Laying of flowers. Monument province of Gelderland Airborne Museum, Oosterbeek. Informatie: 026 3513100 Airborne Museum, Oosterbeek, Info: +31(0)26 3513100 11.00 uur Jaarvergadering Arnhem 1944 Fellowship 11.00 hrs Annual meeting Arnhem 1944 Fellowship - Zaal Lebret, Zaal Lebret, Lebretweg51, Oosterbeek- Info: 06-22882025 Lebretweg 51, Oosterbeek Info: +31(0)6-22882025 Zaal open 10.30 u - vergadering 11.00 u. Location open 10.30 hrs - Meeting 11.00 hrs. 15.00 uur Airborne monument herdenking Nassaustraat Arnhem. 15.00 hrs Wreath laying Airborne Monument Nassaustraat Arnhem Informatie: 026-3510572 Information: +31 (0)26-3510572 19.00 uur Officiële herdenking en kranslegging Airborne Monument 19.00 hrs Official Commemoration and wreath-laying Airborne Monu- Airborneplein, Arnhem, Gemeente Arnhem ment, Airborne Square, Arnhem, Municipality of Arnhem Informatie: 026-3774611 Information: +31(0)26-3774611 ZATERDAG 21 SEPTEMBER 2019 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2019 09.30 uur Luchtlandingen en herdenking met kranslegging, 09.30 - 16.30 Parachute drop, commemoration and wreath-laying. -

Urban and Architectural Revival for Public Transport Infrastructure in the Netherlands Corinne Tiry

F Railway Universal Designs and Architectural Features eature Urban and Architectural Revival for Public Transport Infrastructure in The Netherlands Corinne Tiry Two major rail infrastructure projects in the Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht). Both However, the high population density and Netherlands are now moving ahead projects mesh with the Dutch government’s close proximity of cities in the Randstad rapidly, changing cityscapes by the end of energetic strategy to improve national actually represent an asset for development the decade. The first is an extension of the mobility and promote transportation modes of transit networks, explaining why the North European high-speed link (HSL) rail other than the automobile. The high urban Ministry of Transport, Public Works and network for major cities within the country, concentration in the centre of the country Water Management has decided to invest with the southern part of the network is one reason why congestion has gradually in an exciting light rail project that can planned to begin operations in April 2007 grown to a critical level on trunk roads in compete well with the automobile over (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The second, expected this small area—the Randstad conurbation short distances of around 10 to 20 km. The to be in service in 2008, is the RandstadRail alone has a population of 7.3 million, Ministry signed an agreement with the urban tram–train rail network (Fig. 2) in the representing 46% of the nation’s region of Rotterdam and the Haaglanden southern part of the Randstad conurbation population in just 25% of the total area conurbation to establish RandstadRail (metropolitan region of Amsterdam, (Tables 2 and 3). -

Introduction Day To

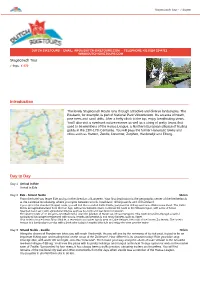

Stagecoach Tour - 7 dagen DUTCH BIKETOURS - EMAIL: [email protected] - TELEPHONE +31 (0)24 3244712 - WWW.DUTCH-BIKETOURS.COM Stagecoach Tour 7 days, € 570 Introduction The lovely Stagecoach Route runs through attractive and diverse landscapes. The Posbank, for example, is part of National Park Veluwezoom. It’s an area of heath, pine trees and sand drifts. After a hefty climb to the top, enjoy breathtaking views. You’ll also visit a riverbank nature reserve as well as a string of pretty towns that used to be members of the Hansa League, a Northern European alliance of trading guilds in the 13th-17th Centuries. You will pass the former Hanseatic towns and cities such as Hattem, Zwolle, Deventer, Zutphen, Harderwijk and Elburg. Day to Day Day 1 Arrival in Ede Arrival in Ede Day 2 Ede - Strand Nulde 56 km From the hotel you leave Ede and go in the direction of Lunteren. Your first destination is the geographic center of the Netherlands at the Lunterse Goudsberg, where you cycle between woods, heathland, drifting sands and old farmland. If you opt for the standard (longer) route, you will find the so-called Celtic Fields, just past the drifting sand area Wek eromse Zand. The Celtic Fields are agricultural land from the Iron Age, with a reconstructed farm. Continue the route to the Veluwe region, with a mix of forest, heathland and sand with agricultural villages such as Kootwijk and Garderen in between. The shorter route of 47 km goes over Barneveld, once the junction of Hanze and Hessen weggen. This route meanders through a varied agricultural landscape interspersed with woods, heaths and peatlands and many hamlets such as Appel. -

Summer Course 2018 Arnhem Business School the Netherlands

European Culture, Business & Entrepreneurship Summer Course 2018 Arnhem Business School The Netherlands Contents Contents ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 The Netherlands ....................................................................................... 2 The Dutch Education System .................................................................... 3 HAN University of Applied Sciences.......................................................... 5 Arnhem Business School ........................................................................... 6 Summer Course: European Culture, Business and Entrepreneurship .......... 7 Course Content ............................................................................................. 9 Arnhem Campus ......................................................................................... 11 Travel / Public Transport ............................................................................ 13 Immigration requirements ......................................................................... 14 Arnhem City Region .................................................................................... 15 Fun Facts about the Netherlands ............................................................... 16 1 Introduction The Netherlands The Netherlands is a Kingdom. Its official name is the Kingdom of the Netherlands. -

Regional Versus City Marketing: the Hague Region Case

Regional Marketing: The Hague Region Case Name : Petra Meijer Student number : 297508pm Study : Urban, Ports & Transport economics University : Erasmus University Rotterdam Faculty : Erasmus school of Economics Supervisor : Dr. E. Braun Date of publication : December 17, 2009 Regional Marketing: The Hague Region Case Petra Meijer Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Preface This thesis on the feasibility of regional marketing was conducted as part of the Masters’ Program in Urban, Port and Transport Economics at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. The aim of this thesis is to contribute to the academic place marketing literature, and to develop an integrated regional marketing framework in order to test the feasibility, and to show the success factors and barriers of regional marketing. More research and case studies are needed to improve the integrated regional marketing framework. I could not have written this thesis without the help of a number of people. First of all, I would like to thank all the interviewees for their time and effort. In particular I would like to thank my contact person at The Hague city region J. Heidekamp and my supervisor at the Erasmus University Dr. E. Braun for their advice and encouragement. Furthermore I would like to thank Mrs. Milne for her recommendations on my English writing style, Ms. Vlieland for her beautiful drawing and MSc. Kayali for her help in “pimping” my thesis. And last but not least I would like to thank my parents for their support. In particular I would like to thank my mother for her constant critical input. We had our disagreements every once in a while but this finally resulted in a thesis I am proud of, although a thesis can always be improved.