Regional Versus City Marketing: the Hague Region Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEPT Study Tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019

Facilitating Electric Vehicle Uptake LEPT study tour Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam 12-14 May 2019 1 Background Organising the study tour The London European Partnership for Transport (LEPT) has sat within the London Councils Transport and Mobility team since 2006. LEPT’s function is to coordinate, disseminate and help promote the sustainable transport and mobility agenda for London and London boroughs in Europe. LEPT works with the 33 London boroughs and TfL to build upon European knowledge and best practice, helping cities to work together to deliver specific transport policies and initiatives, and providing better value to London. In the context of a wider strategy to deliver cleaner air and reduce the impact of road transport on Londoners’ health, one of London Councils’ pledges to Londoners is the upscaling of infrastructures dedicated to electric vehicles (EVs), to facili- tate their uptake. As part of its mission to support boroughs in delivering this pledge and the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, LEPT organised a study tour in May 2019 to allow borough officers to travel to the Netherlands to understand the factors that led the country’s cities to be among the world leaders in providing EV infrastructure. Eight funded positions were available for borough officers working on electric vehicles to join. Representatives from seven boroughs and one sub-regional partnership joined the tour as well as two officers from LEPT and an officer that worked closely on EV charging infrastructure from the London Councils Transport Policy team (Appendix 1). London boroughs London’s air pollution is shortening lives and improving air quality in the city is a priority for the London boroughs. -

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands Korthals Altes, W.K., Van Rij, E. (2013) Planning the horticultural sector: Managing greenhouse sprawl in the Netherlands, Land Use Policy, 31, 486-497 Abstract Greenhouses are a typical example of peri-urban land-use, a phenomenon that many planning systems find difficult to address as it mixes agricultural identity with urban appearance. Despite its urban appearance, greenhouse development often manages to evade urban containment policies. But a ban on greenhouse development might well result in under-utilisation of the economic value of the sector and its potential for sustainability. Specific knowledge of the urban and rural character of greenhouses is essential for the implementation of planning strategies. This paper analyses Dutch planning policies for greenhouses. It concludes with a discussion of how insights from greenhouse planning can be applied in other contexts involving peri-urban areas. Keywords: greenhouses; horticulture; land-use planning; the Netherlands; peri-urban land-use 1 Introduction The important role played by the urban-rural dichotomy in planning practice is a complicating factor in planning strategies for peri-urban areas, often conceptualised as border areas (the rural-urban fringe) or as an intermediate zone between city and countryside (the rural-urban transition zone) (Simon, 2008). However, “[t]he rural-urban fringe has a special, and not simply a transitional, land-use pattern that distinguishes it from more distant countryside and more urbanised space.” (Gallent and Shaw, 2007, 621) Planning policies tend to overlook this specific peri-environment, focusing rather on the black-and-white difference between urban and rural while disregarding developments in the shadow of cities (Hornis and Van Eck, 2008). -

FRÉ ILGEN MA BIOGRAPHY March 2017

painter, sculptor, theorist, curator FRÉ ILGEN MA BIOGRAPHY March 2017 Born in Winterswijk, the Netherlands; lives and works in Berlin, Germany; EDUCATION 1968-1974 Atheneum A, lyceum, the Netherlands; 1974-1975 studies psychology at the Royal University Leiden, Leiden, Netherlands; 1975-1978 studies teaching painting/sculpture at the NLO ZWN, Delft, Netherlands; 1978-1981 studies fine art at the Academy for Fine Arts Rotterdam (BA); 1988 MA painting/sculpture at the AIVE Art Department, the Netherlands; EMS (Engineering Modeling System) certificate, AIVE Eindhoven, the Netherlands; 1981 - .. self-study in art history, art theory, various fields of science, psychology, philosophy (both Occidental and Oriental philosophy); ACTIVITIES 1985-1987 member of the board of several associations of artists, co-organizer of several exhibitions on sculpture; representative of these associations in several governmental art committees in The Hague and Utrecht; member of selection-committee for art in public spaces in Hazerswoude, Alphen a/d Rijn, Cromstrijen; from 1986 founder and president of the international active PRO Foundation; organizer of some 40 international exhibitions, symposia and multi-disciplinary conferences in various countries in Europe and the US; publisher of the PRO Magazine 1987-1991, and various catalogues; Coordinator Studium Generale, Academy for Industrial Design Eindhoven, the Netherlands; 1992-1994 Manager Communications European Design Centre Ltd, Eindhoven, the Netherlands; founding member of the Vilém Flusser Network -

Polderkalender Kidsproof Editie

17 Avontuurlijke 16 POLDERKALENDER WOUBRUGGE TER AAR wandelingen LEIDERDORP door boerenland LEIDEN 15 KIDSPROOF EDITIE ONTDEK HET ECHTE BOERENLEVEN! Wandel dwars door weilanden, over loopbruggetjes en ZOETERWOUDE-RIJNDIJK 4 seizoenen langs boerderijen. Wat een avontuur! Je kunt zomaar oog 14 in het ALPHEN A/D RIJN in oog komen te staan met een koe of schaap. De boeren Tip! LAND VAN WIJK hebben allerlei routes gemaakt. Ze zijn in het land gemar- Neem contant geld mee 3 1 & WOUDEN keerd, iedere route heeft zijn eigen kleur. Welk Boerenland- om onderweg iets lekkers 2 pad ga jij ontdekken? te kopen in één van de 11 ZOETERWOUDE 4 13 boerderijwinkels! 5 6 12 HAZERSWOUDE-DORP Boeren werken elke dag, zomer en winter, om te zorgen voor gezond, duurzaam en 8 7 (h)eerlijk voedsel. Wat gebeurt er op de boerderij? Wat valt er te ontdekken in de boeren- natuur? Wat is er voor kinderen te doen in de polders? Samen met Stichting Land van Wijk & Wouden hebben we voor ieder seizoen leuke tips Let op: tijdens het broed- ZOETERMEER 9 10 BOSKOOP seizoen (15 maart tot en met verzameld om het echte boerenleven en de oer-Hollandse polders rondom Zoetermeer 15 juni) zijn de boerenlandpaden en Leiden te ontdekken. We hebben gewandeld door weilanden, gefietst, geplukt, gesloten voor publiek. geproefd en geknuffeld met de schattigste lammetjes. Wat is het leuk in de polder! Het Land van Ontdekken en Genieten Dus trek je laarzen aan, pak je picknick- 1. BOER EN GOED: boerderijwinkel, ontdekpad en start Boerenkaasroute mand, stap op de fiets en ontdek het Spannende fietstochten door polder 2. -

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region And

Title: Study Visit Energy Transition in Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region Together with the Province of Gelderland and the AER, ERRIN Members Arnhem Nijmegen City Region and the Cleantech Region are organising a study visit on the energy transition in Gelderland (NL) to share and learn from each other’s experiences. Originally, the study visit was planned for October 31st-November 2nd 2017 but has now been rescheduled for April 17-19 2018. All ERRIN members are invited to participate and can find the new programme and registration form online. In order to ensure that as many regions benefit as possible, we kindly ask that delegations are limited to a maximum of 3 persons per region since there is a maximum of 20 spots available for the whole visit. Multistakeholder collaboration The main focus of the study visit, which will be organised in cooperation with other interregional networks, will be the Gelders’ Energy agreement (GEA). This collaboration between local and regional industries, governments and NGOs’ in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands, has pledged for the province to become energy-neutral by 2050. It facilitates a co-creative process where initiatives, actors, and energy are integrated into society. a A bottom-up approach The unique nature of the GEA resides in its origin. The initiative sprouted from society when it faced the complex, intricate problems of the energy transition. The three initiators were GNMF, the Gelders’ environmental protection association, het Klimaatverbond, a national climate association and Alliander, an energy network company. While the provincial government endorses the project, it is not a top-down initiative. -

Activiteiten Stichting Land Van Wijk En Wouden Voor De Regio Holland Rijnland Hannie Korthof, April 2014

Activiteiten Stichting Land van Wijk en Wouden voor de regio Holland Rijnland Hannie Korthof, april 2014 In het kort De Stichting is de uitvoeringsorganisatie van de vroegere Gebiedscommissie Land van Wijk en Wouden. De Stichting zet zich in voor: ‐ Het versterken en behouden van de identiteit van het gebied ‐ Het vergroten van de betekenis voor de stad ‐ Het verbeteren van de stad‐landrelatie ‐ Het versterken van de plattelandseconomie Speerpunten: ‐ Recreatie en toerisme ‐ Streekproducten ‐ Natuur en cultuurhistorie ‐ Promotie van de regio en educatie Werkgebied: ‐ De regio tussen Leiden, Leiderdorp, Alphen, Zoetermeer en Leidschendam‐Voorburg en steeds meer de hele regio Holland Rijnland Financiën: ‐ Jaarlijks bijdragen van de gemeenten Zoeterwoude, Alphen, Leiden, Leiderdorp en Zoetermeer en het Hoogheemraadschap Rijnland ‐ Inkomsten uit projecten via subsidies, fondsen, sponsoring, bijdragen van gemeenten, etc. De organisatie bestaat uit het projectbureau met twee vaste en twee tijdelijke medewerkers, het bestuur en het gebiedsplatform Het bestuur: ‐ Burgemeester Laila Driessen van Leiderdorp, voorzitter ‐ Gerard van der Hulst van LTO, vicevoorzitter ‐ Theo van Leeuwen, voorzitter Groene Klaver, secretaris ‐ Frank de Wit, wethouder van de gemeente Leiden ‐ Pieter Hellinga van Hoogheemraadschap Rijnland Activiteiten in de regio Holland Rijnland Kaartenset Recreative kaartemn met routes, fietsknooppunten,boerderijen met huisverkoop, horeca, botenverhuur, cultuurhistorische informatie, etc. Er is een nieuwe set in de maak. Het worden nu vijf kaarten. De regio Alphen‐Nieuwkoop komt erbij. Bovendien krijgen nu de Limes en de Oude Hollandse Waterlinie een plek op de kaarten. 1 Streekproducten Een website voor Holland Rijnland die laat zien waar je bij de boer aan huis producten kunt kopen, waar je ze op de markt en in de supermarkt of winkel kunt kopen, en hoe je ze online kunt bestellen. -

Bijlage 3: Projectenatlas PZI

Bijlage 3: Projectenatlas PZI In hoofdstuk 1 is beschreven wat de ambitie is van de provincie Zuid-Holland voor wat betreft het beheer en aanleg van provinciale infrastructuur. De Projectenatlas is een selectie van projecten uit de paragrafen voor aanleg, verbetering en beheer van de provinciale infrastructuur. Voor aanleg en verbetering met name de projecten waar aanzienlijke kosten mee gemoeid zijn en die politiek en bestuurlijk de aandacht hebben en voor onderhoud een selectie die de diversiteit van de werkzaamheden aantoont. De selectie geeft daarmee een overzicht van de verschillende onderdelen waarmee uitvoering wordt gegeven aan de ambitie van de provincie Zuid-Holland. De bestaande regeling projecten is alleen van toepassing op de projecten voor aanleg en verbetering (projecten 1 t/m 19). Van de volgende projecten aanleg en verbetering is een factsheet met meer informatie opgenomen: 1. Uitvoeringsprogramma Fiets 2. HOV-net Zuid-Holland-Noord 3. Programma R-net 4. Programma P+R Voorzieningen 5. RijnlandRoute 6. Ontwikkeling buscorridor Noordwijk - Schiphol 7. N207 Corridor: Vredenburghlaan 8. N207 Corridor: Passage Leimuiden 9. N207 Zuid, Bentwoudlaan, Verlengde Bentwoudlaan en maatregelen Hazerswoude-Dorp 10. N211: Wippolderlaan 11. N213: Centrale As Westland 12. Bereikbaarheid Bollenstreek (vervolg Duinpolderweg) 13. Vervangen Steekterbrug 14. Verbreding Delftse Schie 15. Kruising N214/N216 16. N215 groot onderhoud en verkeersveiligheidsmaatregelen Van de volgende projecten voor beheer en onderhoud is een factsheet met meer informatie opgenomen: 17. N468 Schipluiden 18. N223 Den Hoorn 19. Beweegbare kunstwerken vaarwegtraject 1 Rijn-Schiekanaal 20. Beweegbare kunstwerken vaarwegtraject 10 Merwedekanaal 21. Oevers traject 6 Heimanswetering 22. Steunpunt Coenecoop 23. N228 Veiliger! PZH-2020-747840424 dd. -

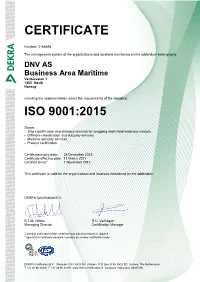

ISO 9001 Certificate

CERTIFICATE Number: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum belonging to: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway including the implementation meets the requirements of the standard: ISO 9001:2015 Scope: - Ship classification and statutory services for seagoing and inland waterway vessels - Offshore classification and statutory services - Maritime advisory services - Product certification Certificate expiry date: 28 December 2023 Certificate effective date: 11 March 2021 Certified since*: 1 November 2013 This certificate is valid for the organizations and locations mentioned on the addendum. DEKRA Certification B.V. j E B.T.M. Holtus R.C. Verhagen Managing Director Certification Manager © Integral publication of this certificate and adjoining reports is allowed * against this certifiable standard / possibly by another certification body DEKRA Certification B.V. Meander 1051, 6825 MJ Arnhem P.O. Box 5185, 6802 ED Arnhem, The Netherlands T +31 88 96 83000 F +31 88 96 83100 www.dekra-certification.nl Company registration 09085396 page 1 of 13 ADDENDUM To certificate: 2166898 The management system of the organizations and locations of: DNV AS Business Area Maritime Veritasveien 1 1363 Høvik Norway Certified organizations and locations: DNV GL Angola Serviços Limitada DNV GL Argentina S.A Belas Business Park, Etapa V, Avenida Leandro N. Alem 790, 9th andar, Torre Cuanza Sul, Piso 6 – CABA, Talatona, Luanda Buenos Aires - C1001AAP Angola Argentina DNV GL Australia Pty -

Waterrijk Wonen in De Randstad INHOUD

fase 2 Eengezinswoningen type 5.1 en 5.4 en twee-onder-één-kapwoningen type 6.0 Roelofarendsveen Waterrijk wonen in de Randstad INHOUD 4. Wonen in De Poelen 6. Alle faciliteiten in de buurt 7. Voorzieningen Roelofarendsveen 8. Waterrijk wonen op hoog niveau 11. Vind gemakkelijk uw ideale huis 14. Wonen met vakantiegevoel 16. De Poelen 5.1 | Eengezinswoning 24. De Poelen 5.4 | Eengezinswoning 32. De Poelen 6.0 | Twee-onder-één-kapwoning 44. Duurzaam wonen 45. Klaar voor de toekomst 46. Sanitair In Roelofarendsveen – direct aan het Braassemermeer – is een nieuwe woonwijk Roelofarendsveen volop in ontwikkeling: Aan de Braassem. Op deze unieke plek in het Groene Hart Schiphol 10 min. komen circa 1.200 woningen op royaal opgezette wooneilanden. Inmiddels zijn de eerste deelplannen met riante en goed afgewerkte woningen verkocht, opgeleverd Leiden 15 min. en bewoond. Met De Poelen fase 2 start nu de bouw van 75 duurzame, moderne Hoofdorp 20 min. en energiezuinige eengezinswoningen en twee-onder-één-kapwoningen. Pal Amsterdam gelegen tussen het gezellige en vernieuwde centrum van Roelofarendsveen en het Amsterdam 20 min. Schiphol wijdse water van de Braassemermeer. De woningen zijn voorzien van diepe en Hoofddorp Zoetermeer 20 min. zonnige achtertuinen. Den Haag 25 min. Noordwijk In de Poelen fase 2 worden volgens twee verschillende bouwconcepten woningen Noordwijk 30 min. gebouwd. Voorliggende brochure heeft betrekking op PlusWonen. Roelof- arends- veen Leiden Den Haag Zoetermeer CENTRAAL ROELOFARENDSVEEN Centrale locatie Alles bij de hand Roelofarendsveen ligt heel centraal tussen de grote steden De nieuwe wijk De Poelen ligt ideaal tussen het levendige Amsterdam, Leiden, Utrecht en Den Haag. -

WESTERTERP CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Klaas R Westerterp Education MSc Biology, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971. Thesis: The energy budget of the nestling Starling Sturnus vulgaris: a field study. Ardea 61: 127-158, 1973. PhD University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1976. Thesis: How rats economize – energy loss in starvation. Physiol Zool 50: 331-362, 1977. Professional employment record 1966-1971 Teaching assistant, Animal physiology, University of Groningen 1968-1971 Research assistant, Institute for Ecological Research, Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1971 Lecturer, Department of Animal Physiology, University of Groningen 1976 Lecturer, Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen 1977 Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Stirling, Scotland 1980 Postdoc, Animal Ecology, University of Groningen and Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1982 Senior lecturer, Department of Human Biology, Maastricht University 1998 Visiting professor, KU Leuven, Belgium 2001 Professor of Human Energetics, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University Research The focus of my work is on physical activity and body weight regulation, where physical activity is measured with accelerometers for body movement registration and as physical activity energy expenditure, under confined conditions in a respiration chamber and free-living with the doubly labelled water method. Management, advisory and editorial board functions Head of the department of Human Biology (1999-2005); PhD dean faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (2007- 2011); member of the FAO/WHO/UNU expert group on human energy requirements (2001); advisor Philips Research (2006-2011); advisor Medtronic (2006-2007); editor in chief Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2009-2012); editor in chief European Journal of Applied Physiology (2012-present). -

Route Arnhem

Route Arnhem Our office is located in the Rhine Tower From Apeldoorn/Zwolle via the A50 (Rijntoren), commonly referred to as the • Follow the A50 in the direction of Nieuwe Stationsstraat 10 blue tower, which, together with the Arnhem. 6811 KS Arnhem (green) Park Tower, forms part of Arnhem • Leave the A50 via at exit 20 (Arnhem T +31 26 368 75 20 Central Station. Center). • Follow the signs ‘Arnhem-Center’ By car and the route via the Apeldoornseweg as described above. Parking in P-Central Address parking garage: From Nijmegen via the A325 Willemstunnel 1, 6811 KZ Arnhem. • Follow the A325 past Gelredome stadium From the parking garage, take the elevator in the direction of Arnhem Center. ‘Kantoren’ (Offices). Then follow the signs • Cross the John Frost Bridge and follow ‘WTC’ to the blue tower. Our office is on the the signs ‘Centrumring +P Station’, When you use a navigation 11th floor. which is the road straight on. system, navigate on • After about 2 km enter the tunnel. ‘Willemstunnel 1’, which will From The Hague/ Utrecht (=Den Bosch/ The entrance of parking garage P-Central lead you to the entrance of Eindhoven) via the A12 is in the tunnel, on your right Parking Garage Central. • Follow the A12 in the direction of Arnhem. By public transport • Leave the A12 at exit 26 (Arnhem North). Trains and busses stop right in front of Via the Apeldoornseweg you enter the building. From the train or bus Arnhem. platform, go to the station hall first. From • In the built-up area, you go straight down there, take the escalator up and then turn the road, direction Center, past the right, towards exit Nieuwe Stationsstraat. -

Ontwikkelstrategie HOV Zoetermeer – Rotterdam

Ontwikkelstrategie HOV Zoetermeer – Rotterdam Bestuurlijke rapportage september 2020 Inhoudsopgave ▪ Context HOV Zoetermeer – Rotterdam pag. 3 ▪ Rekenvariant pag. 5 ▪ Verstedelijkingsscenario’s pag. 6 ▪ Effecten op kerndoelen: pag. 8 ▪ Vervoerwaarde pag. 9 ▪ Efficiënt en rendabel pag. 10 ▪ Kansen voor mensen en concurrerende economie pag. 11 ▪ Bijdrage aan verduurzaming pag. 12 ▪ Overzicht effecten pag. 13 ▪ Eerste uitwerking MKBA pag. 14 ▪ Conclusies pag. 16 ▪ Vervolg pag. 17 Context ZoRo In het BO MIRT Zuidwest-Nederland van 20 November 2019 is in het kader van het gebiedsgerichte bereikbaarheidsprogramma MoVe, de Adaptieve ontwikkelstrategie Metropolitaan OV en Verstedelijking (AOS) vastgesteld. Eén van de hoofdconclusies daarin is dat de stedelijke verdichting langs hoogwaardig OV het meest bijdraagt aan het versterken van de agglomeratiekracht in de Zuidelijke Randstad. Het sneller, robuuster en frequenter verbinden van economische toplocaties en de inwoners van de Zuidelijke Randstad met HOV draagt daarnaast bij aan het verduurzamen van mobiliteit in de regio en verbeteren van leefbaarheid in de steden. Om de AOS verder vorm te geven is gestart met een ‘preverkenning schaalsprong MOVV’ met daarbinnen een aantal uitwerkingslijnen: ▪ Infrastructuur en knooppunten Oude Lijn ▪ Regionale HOV corridors ▪ MKBA gebiedsprogramma MoVe en financieringspropositie Als onderdeel van de uitwerking van de regionale HOV corridors is voor de HOV verbinding Zoetermeer Rotterdam (ZoRo) afgesproken een ontwikkelpad te verkennen en uit te werken met als eindbeeld lightrail. 3 Context ZoRo Voorliggende studie geeft een eerste uitwerking aan de verkenning en uitwerking van het ontwikkelpad van de ZoRo-verbinding. De studie is tot stand gekomen samen met alle betrokken partners: Zoetermeer, Lansingerland, Rotterdam, MRDH, Zuid-Holland, HTM en RET, en ondersteund door Goudappel Coffeng en APPM.