Copyright Protection for Tattoos: Are Tattoos Copies? Michael C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright Ownership and the Need for Implied Licenses in the Realm of Tattoos Kyle Alan Ulscht

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Copyright Ownership and the Need for Implied Licenses in the Realm of Tattoos Kyle Alan Ulscht Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Ulscht, Kyle Alan, "Copyright Ownership and the Need for Implied Licenses in the Realm of Tattoos" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 596. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/596 Copyright Ownership and the Need for Implied Licenses in the Realm of Tattoos Kyle Alan Ulscht This article argues that there is a need for an implied license to be issued when an individual is tattooed. In spite of a rich history spanning millennia, the legal community has not come up with an adequate system of determining copyright ownership in affixed tattoos. Complicating this lack of certainty in the field of copyright rights in tattoos is the general unwillingness of courts to invoke the de minimus use exception in cases of copyright violation. This unwillingness coupled with the ubiquitous nature of technology and social media could lead virtually every tattooed person to be held to be an infringer and prevent them from a variety of activities ranging from appearing in advertisements, or movies, to more common activities such as posting photos on Facebook, without a complicated trial or trail of paperwork and accounting. Fortunately courts, relying on theories of equity, have invented the concept of implied licenses for instances when a party commissions a work but does not meet the more formal requirements to own the copyright rights of that work. -

Baltimore Tattoo Shop Makes Week 9 Exit

Baltimore Tattoo shop makes week 9 exit Posted by TBNDavid On 08/09/2017 On the ninth episode of “Ink Master,” Season 1 Veteran Tommy Helm and Marvin Silva of Empire State Studio (Amityville, NY) entered the competition. Following a flash challenge in which contestants demonstrated proportion by applying plaster to a large canvas to create a relief sculpture, an old classic art form, they then had to design Pin-Up Girl tattoos. In the end, the judges felt that Pinz and Needles (Baltimore, MD) did not have what it takes to be the next “Ink Master Master Shop.” After the ninth week of competition the shops left competing are: • Allegory Arts – Florence, AL o Ulyss Blair (@Ulyss_Blair) - Co-owner/Artist o Eva Huber (@eva_jean) – Co-owner/Artist • Artistic Skin Designs – Indianapolis, IN o April Nicole (@April_Nicole) – Artist o Dane Smith (@danesmithtattoo) – Artist • Basilica Tattoo – Las Vegas, NV o Christian Buckingham (@ChristianBuckingham) – Co-owner/Artist o Noelin Wheeler (@Noelin.Tattoo) – Artist • Black Cobra Tattoos – Sherwood, AR o Katie McGowan (@katietattoos) – Artist o Matt O’Baugh (@mattobaugh) – Owner • Classic Trilogy Tattoo – Syracuse, NY o Thom Bulman (@Bulman_Tattoos) – Owner/Artist o Derek Zielinski (@derek_zielinski_artist) – Artist • Empire State Studio – Amityville, NY o Tommy Helm (@tommyhelmart) – Owner o Marvin Silva (@iammarvinsilva) – Artist • Old Town Ink – Scottsdale, AZ o Bubba Irwin (@Bubbaitattoos) – Artist o DJ Tambe (@djtambe) – Artist • Unkindness Art – Richmond, VA o Erin Chance (@ErinChanceTattoo) – Owner/Artist o Doom Kitten (@doomkitten) – Artist Coming up on the next episode of “Ink Master” on Tuesday, August 15 at 10pm ET/PT – The final Veteran shop returns to fight for the first ever title of Master Shop and skull picks are key to the precision strike leveled at the opposing alliance. -

PM0705-38 Pgsc4,C1-11.Qxd

★ BALTIMORE TATTOO ARTS ★ MATEO SIGWERTH ★ ATLANTA’S SILVER FOX TATTOO ★ BUYER’S GUIDE FOR BODY MODIFICATION PROFESSIONALS JULY 2018 #194 USA $10.00 Canada $10.00 Publications Mail Agreement #40069018 staff JULY Publisher Ralph Garza ISSUE 194 ISSUE Editor-In-Chief R Cantu Account Executive Jennifer Orellana [email protected] 505-332-3003 Managing Editor Sandy Caputo [email protected] Art Director SOM Remy [email protected] 14 12 Silver Fox Tattoo Show Feature: Contributing Writers Tiny Homes Elayne Angel David Pogge 16 Austin Ray Darin Burt Tanya Madden Spotlight Ask Angel 34 Show Expo 34 Executive Assistant 30 Spotlight: Richard DePreist [email protected] Neilmed 505-275-6049 Baltimore Tattoo 38 Arts Convention Artist Gallery Baltimore Tattoo 9901PAIN MagazineAcoma Rd. SE Arts Convention Albuquerque, NM 87123 [email protected] 40 General Inquiries: PAINful Classic: [email protected] www.painmag.com Everyone Loves Pub Subs www.facebook.com/painmagazine Artist Profile Subscriptions: [email protected] 36-37 Printed in Canada Mateo Sigwerth Publications Mail Agreement #40069018 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: 737 Moray St., Winnipeg MB, Canada, R3J 3S9 advertisersindex contacts 505-275-6510 Fax Body Art Solutions 41 Nat-A-Tat2 39 505-275-6049 Editorial Body Shock 11 Needlejig 27 cover sponsor Desert Palms Emu Ranch 17 Neilmed Aftercare Front Cover 34 Eternal Ink 4 Painful Pleasures 5, 13, 29, Inside Back Cover NeilMed NeilcleanseNeilmed Piercing Aftercare saline spray is Face and Body 35 Papa Tattoo Supply 6 isotonic, drug free, preservative free, no burning or stinging. Sterile saline solution that cleanses minor Exposed Temptations Tattoo New Artist 21 Papillons Tattoo Supply 7 wounds and scrapes without any burning or stinging. -

Size 6 Height 5'4”

Size 6 Height 5’4” Weight 130 VALERIE SAUNDERS 480-577-8552 Eyes Hazel Voice Alto www.valeriesaunders.biz [email protected] Shoe 8M Hat 7¼ Glove 7¼ FILMS - Crew Member* and Acting TOMBSTONE* (Specific scenes filmed at Old Tucson) Worked on Set - Props and Lighting Cinergi Pictures SONGS OF THE DESERT* (BYU Dance Department) Production Assistant Brigham Young University (BYU) REQUITED* Supplied Additional Wardrobe & Jewelry; Saloon Girl (Finalist for the 2012 Student Academy Awards) Point Park University, Madeline Puzzo Director ON THE THIRD DATE (SAG Points) Stella Cinebrau Productions PATTERN: RESPONSE (Several Film Festival Winners) Lead Scientist Synthetic Human Pictures ATTACK OF THE MOTHER (Webisode 2) Mother - Mr. E Comics A Thin Line Between Productions THE LAST DANCE (Shown at Cannes Film Festival) Vocalist and Harmonizer (Supporting) Future Legend Productions 600 MILES Mother and Gun Shopper Tucson AZ BILL & TED’S EXCELLENT ADVENTURE Ensemble Orion Pictures & Nelson Entertainment DRIVING TO PHOENIX All Four Different Waitresses jDavid Productions LETTERS TO THE SKY Grandmother of Rachel Portledge Pictures LAUGH-IN (Industrial) Joanne Worley USAA CANADIAN MUSIC VIDEO (Industrial) Vocalist and Dancer CMV SEARLE PHARMACY (Industrial) Ensemble Searle PHOENIX FILM FESTIVAL (Advertisement) Ensemble Phoenix Film Festival SEA WORLD Roller Coaster Rider Sea World MODELING FRAMESI Hair Scottsdale AZ SEMLER SCIENTIFIC Hand and Foot Phoenix AZ TELEVISION OUTRAGEOUS ARIZONA (Episode 1) Madam; Housewife True West Magazine; PBS, Phoenix, AZ OUTRAGEOUS -

Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist Vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms Brayndi L

Mitchell Hamline Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 1 Article 8 2016 Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms Brayndi L. Grassi Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Grassi, Brayndi L. (2016) "Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Waiver) Forms," Mitchell Hamline Law Review: Vol. 42: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr/vol42/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mitchell Hamline Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. Grassi: Copyrighting Tattoos: Artist vs. Client in the Battle of the (Wai 2 (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2016 7:52 PM COPYRIGHTING TATTOOS: ARTIST VS. CLIENT IN THE BATTLE OF THE (WAIVER) FORMS* Brayndi L. Grassi† I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 44 II. BRIEF HISTORY OF COPYRIGHT LAW IN NEW MEDIUMS ........... 46 III. FIRST INSTANCE OF COPYRIGHTS IN TATTOOS: REED V. NIKE, INC. ................................................................................. 47 IV. ARE TATTOOS COPYRIGHTABLE? ............................................. 48 A. Tattoos Meet All of the Requirements of the Copyright Act ...... 49 1. Originality .................................................................... 49 2. Authorship ................................................................... -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

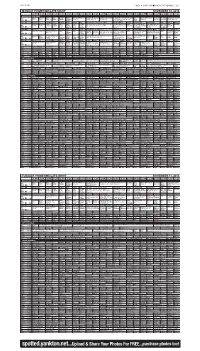

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Ink Master: Angels': New, All-Women Series Is "Inspiring," Showrunner Says by Amanda Buckle June 2017

https://mic.com/articles/178923/ink-master-angels-new-all-women-series-is-inspiring- showrunner-says#.q1nb1r7bX 'Ink Master: Angels': New, all-women series is "inspiring," showrunner says By Amanda Buckle June 2017 Ink Master alums Ryan Ashley, Kelly Doty, Nikki Simpson and Gia Rose are here to stay. The tattoo artists proved to be top competitors in season eight of the Spike reality series and in March, the network announced that the women would be returning for their own one-hour special, Ink Master: Angels. On Monday Spike revealed that the special has now been turned into a series. Ink Master: Angels will consist of 10 episodes and debut this fall. The series will follow Ryan, Kelly, Nikki and Gia as they "travel the country and go head-to- head with some of America's most talented tattoo artists." The twist is that the competitors facing the four women will be fighting for a spot on season 10 of Ink Master, which will debut in 2018. The announcement doesn't come as a big surprise as Ink Master pulled in a 57% female audience for its eighth season — the largest number of female viewers in franchise history. The eighth season also crowned Ryan Ashley as its first female winner. For Ink Master showrunner and executive producer Andrea Richter, the idea to bring the women back came together "pretty quickly." "It's interesting having been there and filmed them for the first time and seeing all of them meet for the first time and bond," Richter said. "I think it was an obvious choice. -

Matilda-Playbill-FINAL.Pdf

We’ve nevER been more ready with child-friendly emergency care you can trust. Now more than ever, we’re taking extra precautions to keep you and your kids safe in our ER. AdventHealth for Children has expert emergency pediatric care with 14 dedicated locations in Central Florida designed with your little one in mind. Feel assured with a child-friendly and scare-free experience available near you at: • AdventHealth Winter Garden 2000 Fowler Grove Blvd | Winter Garden, FL 34787 • AdventHealth Apopka 2100 Ocoee Apopka Road | Apopka, Florida 32703 Emergency experts | Specialized pediatric training | Kid-friendly environments 407-303-KIDS | AdventHealthforChildren.com/ER 20-AHWG-10905 A part of AdventHealth Orlando Joseph C. Walsh, Artistic Director Elisa Spencer-Kaplan, Managing Director Book by Music and Lyrics by Dennis Kelly Tim Minchin Orchestrations and Additional Music Chris Nightingale Presenting Sponsor: ADVENTHEALTH VIP Sponsor: DUKE ENERGY Matilda was first commissioned and produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered at The Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England on 9 November 2010. It transferred to the Cambridge Theatre in the West End of London on 25 October 2011 and received its US premiere at the Shubert Theatre, Broadway, USA on 4 March 2013. ROALD DAHL’S MATILDA THE MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI) All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 423 West 55th Street, New York, NY 10019 Tel: (212)541-4684 Fax: (212)397-4684 www.MTIShows.com SPECIAL THANKS Garden Theatre would like to thank these extraordinary partners, with- out whom this production of Matilda would not be possible: FX Design Group; 1st Choice Door & Millwork; Toole’s Ace Hardware; Signing Shadows; and the City of Winter Garden. -

Evaluation of Tattoo Artists' Perceptions of Tattoo Regulations in the United States

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2016 Evaluation of Tattoo Artists' Perceptions of Tattoo Regulations in the United States Jessica L.C. Sapp Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Health Services Administration Commons, and the Other Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Sapp, Jessica L.C., "Evaluation of Tattoo Artists' Perceptions of Tattoo Regulations in the United States" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1410. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1410 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF TATTOO ARTISTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF TATTOO REGULATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES by JESSICA LOUISE CREWS SAPP (Under the Direction of Robert Vogel) ABSTRACT Background: With the increasing popularity in recent years, tattoos are no longer considered taboo but rather becoming a mainstream mode of self-expression so the inherent risks associated with tattooing could have a greater impact on the public’s health. Objective: The study aims to gain an understanding and describe the perceptions and opinions of tattoo artists -

Download Catalogue

ARTWORK * AUTOGRAPHS & DOCUMENTS ELIZABETH’S AUCTIONS Sale 151 Ephemera and Books Monday, March 19, 2018 at 6:00PM The Auburn Elks 754 Southbridge St., Auburn, Mass. Preview: 3:00PM to 6:00PM LOT DESCRIPTION PRINTS * HISTORICAL ARCHIVES * SHEET MUSIC * BILLHEADS & LETTERHEADS * TRADE HISTORY* THE SALE WILL BEGIN WITH PICK LOTS OF BOOKS AND OTHER MILITARY * CIVIL WAR * PAMPHLETS * POSTERS * UNCATALOGUED INTERESTING MATERIAL . ADVERTISING * POSTAL HISTORY * PHOTOGRAPHS TRAVEL * MANY LARGE LOTS OF POSTCARDS 001 [Abraham Lincoln (3)] Three prints: “Abraham Lincoln,” ___________________________________________________________ Published by William Smith, Philadelphia. Large folio lithograph, 22”x28.” ca 1861. * “Death of President Lincoln. At Washington D.C., 010 American postcards (450-500). New England city and town April 15, 1865.” Currier and Ives, NY, 1865. Medium folio, 16”x12”. views, holidays, topicals including ships, expositions, realphoto, etc. Mild damp stains. * Novelty portrait of Lincoln, by N. Chasin. 16”x18”. Early to linen periods. Fine. (est. $100-150) Figural details composed of words from speeches. Cropped.* Must be seen. (est. $100-150) 011 American postcards (300-325). New England local views, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut; holiday and 002 [Abraham Lincoln] “The Nation in Tears, In Memoriam.” topical cards. Early and white-border periods. VG overall. Music by Konrad Treuer, Words by R.C. ca 1865 by W. Jennings (est. $100-150) Demorest. 9.5”x11.5” folio sheet with large wood-cut portrait of Lincoln. Archival tape repairs. Must be seen. (est. $125-175) 012 American postcards (425-450). US local views, holidays, exposition and transportation topicals. Early to chrome periods. Fine. 003 Action Comics, illustration art. -

Social Media to the Mainstream

1 SoundCloud Rap Narratives as Pop Star Narratives: From Social Media to the Mainstream Popular music meanings are dependent on the artist understood as a “total star text” (Dyer 1979). There has been much discussion in academia of how digital technology transforms formerly auteurist narratives of popular music creation into stories about collective authorship (Ahonen 2008, 107). Yet central fictions continue to involve the singular figure of the popular music star. Like new technologies before it, social media change how pop music stardom narratives are constructed. Narrative arcs (stories) and narrative forms (how those stories are told) have transformed alongside changes to the communication structures between artist and audience, and shifts in the authenticating mechanisms applied to pop stars. The transition of so-called SoundCloud rappers to the center of the American pop music landscape over the last five years epitomizes these changes. This study looks at how the narratives of SoundCloud rappers are constructed in the exchange between social media and traditional media publications; it assumes artist narratives to be constructed in this dialogic space. Social media events are articulated onto traditional structures of legitimation, and mainstream media canonize social media narratives. The results of this study indicate how artist narratives regularly unfold online, and how those patterns feed into the more familiar dramatic story arcs. Between January 2015 and June 2019, approximately 5–6% of unique artists that appeared on the Billboard Hot 100 could be categorized as “SoundCloud rappers.” This research focuses on a subset of these, artists who entered mainstream consciousness between 2016 and 2018, and can be broadly thought of as the second generation of SoundCloud rappers to make the transition to the mainstream.