The London School of Economics and Political Science Journalists With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectivity – an Ideal Or a Misunderstanding?

Chapter 3 Objectivity – An Ideal or a Misunderstanding? Elsebeth Frey Objectivity is often seen as an emblem of Western journalism, but in the developed countries the notion of objectivity has declined. Still, journalists from other parts of the world point to it as an export of Western, especially American, journalism. At the same time, American journalism teachers impress on their students the futility of objectivity, and Alex Jones writes that ‘we may be living through what could be considered objectivity’s last stand’ (Jones 2009). As Durham states (1998:118) ‘journalistic objectivity has always been a slippery notion’. Research shows that objectivity worldwide ‘is present and locally generated and negotiated in several ways’ (Krøvel et al. 2012:24). The concept of objectivity has many layers, and one could say that the perception of it is tainted with misunderstandings. As Muñoz-Torres (2012) emphasizes, its philosophical origin is rooted in how we see the world, our understanding of what knowledge is and our perception of the truth. Others write about a practical (Jones 2009) or functional (Rhaman 2017) truth as the one journalists are aiming to discern. This study explores objectivity as seen by journalists and journalism students transnationally, although very much rooted in their culture and politics, specifically in Norway, Tunisia and Bangladesh. Are there differences and/or similarities, and if so, what are they? Furthermore, armed with theoretical approaches from Streckfuss (1990) and Muñoz-Torres (2012), among others, the aim of this chapter is to clarify different positions, as well as views among our interviewees. The notion of objectivity in journalism Richard Streckfuss (1990) looked at historical documents in order to trace when and why objectivity was introduced to journalism in the USA. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo

September 2013 Geri Migielicz Missouri Newspaper Hall of Fame will induct 5 during the MPA Con- 7 vention in Kansas City. Bob Linder Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo. Foundation work com- 4 pleted on MPA building 5 in Columbia. Jim Miller Jr. Regular Features President 2 Scrapbook 12 On the Move 10 NIE Report 15 Obituaries 11 Jean Maneke 17 Missouri Press News, September 2013 www.mopress.com Digital Footprint a powerful new tool! Your advertisers want, need online presence ery soon you’re going to start hearing more about stated by Nienhueser. Digital Footprint, the Missouri Press Service’s name “Another goal of this program will be to enhance the rela- Vfor a new package of services you’ll be able to offer to tionship between Missouri Press Service and the newspapers,” local businesses. You will hear a little about Digital Footprint he said. “With better and more frequent promotion of MPS at the MPA Convention in Kansas City. products, we can’t help but generate more revenue Missouri Press will promote Digital Foot- for everyone. We think the newspapers will ap- print to its member newspapers and to po- preciate that.” tential users of the services around the state To help implement this program, the Missouri and country. We’re going to provide member Press board approved the hiring of another sales newspapers with material they can use to pro- person and a graphic designer. Patton, mentioned mote these services in their markets. above, is the designer; the sales person might be We’ve got a new graphics designer, Jeremy on staff by the time you read this. -

A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝

Korean Social Science Journal 2011, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 99~132 Comparative Review A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝ Jae Chul Shim* (Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Korea University) Wan Kyu Jung** (Lecturer, Division of Political Science, Public Administration and Journalism, Wonkwang University) Kyun Soo Kim*** (Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication, Grambling State University) Abstract This study investigates how Korean major dailies covered educational issues regarding universities, and compares its findings with those of leading American newspapers. The results show that Korean newspapers covered the universities much more negatively than their American counterparts did. Korean newspapers also demonstrated lower journalistic standards as compared with the American newspapers. There were some gaps in terms of news values in covering education at the college level between Korean and American newspapers. Nevertheless, these professional gaps were not too wide to be bridged. In addition, Ettema and Glasser’s three new news values of investigative reporting were not unique from the traditional ones in this study. They were mixed with those of fairness and professional reporting. From these findings, we discuss typical characteristics of Korean newspaper coverage and suggest new ways of covering the education beats in South Korea as a newly advanced and democratized country. Key words: Educational Reform, News Values, Comparative Journalistic Standards, Education Reporting, University News, Diversity, New Long Journalism 100 … Jae Chul Shim, Wan Kyu Jung, and Kyun Soo Kim ✝ This paper was originally written in Korean and published in The Korean Journal of Journalism and Communication Studies in 2003. -

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak S.B. Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER, 2006 Copyright 2006 Daniel R. Bersak, All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________ Department of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified By: ___________________________________________________________ Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: __________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director Ethics In Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences on August 11, 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract Like writers and editors, photojournalists are held to a standard of ethics. Each publication has a set of rules, sometimes written, sometimes unwritten, that governs what that publication considers to be a truthful and faithful representation of images to the public. These rules cover a wide range of topics such as how a photographer should act while taking pictures, what he or she can and can’t photograph, and whether and how an image can be altered in the darkroom or on the computer. -

Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19Th Century America

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 4 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Article 5 1977 Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America Dan Schiller Recommended Citation Schiller, D. (1977). Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America. 4 (2), 86-98. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 the whole field of 19th century painterly and literary art. The key assumption of photographic realism-that precisely accurate and complete copies of reality could be produced from symbolic materials-was rather freely translated across numerous visual and verbal codes, and not only within the REALISM, PHOTOGRAPHY accepted realm of art. After first explicating the general sig AND JOURNALISTIC OBJECTIVITY nificance of this increasingly ubiquitous assumption, I will IN 19th CENTURY AMERICA tentatively explore some of its consequences for literature and for journalism. DAN SCHILLER A JOUST WITH "REALISM" When we commend a work of art as being "realistic," we Hostile critics often choose to equate realism per se with commonly mean that it succeeds at faithfully copying events the demonstration of a few apparently basic qualities in or conditions in the "real" world. How can we believe that works of art. Foremost among these is "objectivity." Wellek pictures and writings can be made so as to copy, truly and (1963 :253), for example, defines realism as "the objective accurately, a "natural" reality? The search for an answer to representation of contemporary social reality." Hemmings this deceptively simple question motivates the present essay. -

Roots of Anger3 Notes

The Real Explanation for the Tax Rebellion and the Size of Government H. William Batt, Ph.D., February 16, 2011 The antipathy toward taxes, and by extension toward government itself, has its roots, I believe, in a distortion of economic theory that took place a century ago. Prior to that time, there was a tacit, if not explicit, understanding that the wealth and bounty that grew from common effort along with the gifts of nature should be the source of finance recaptured by society and used to pay for public services. Since surplus economic productivity is jointly produced, it was the proper source of taxation. Only government can appropriately provide these services since they are in today's language "public goods." On the other hand, wealth that was created by the people's own brains and brawn was rightfully theirs and theirs alone. Taxing people's labor, or the products thereof, was not only wrong but was tantamount to theft.1 Today the resentment people feel about taxes on their hard-earned money has reached a point close to delegitimizing the income tax and government itself. Estimates of actual tax cheating are put at about 15 percent, but fully half the population believes that it would be okay to cheat if one wouldn’t be caught.2 It has taken over a century for this all to explode. But taking the long view of tax history one could argue that this is not only understandable but also inevitable. Had economic arrangements been done as they were in earlier times there would likely be far less such resistance to taxation and perhaps even a sense of social duty to pay one’s share of taxes. -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

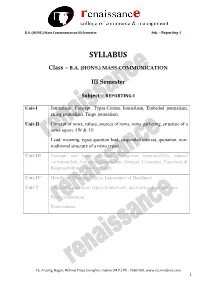

Class – BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester Subject – REPORTING-I Unit-I Journalism: Concept, Types-Citizen Journalism, Embeded journalism, string journalism, Tingo journalism. Unit-II Concept of news, values, sources of news, news-gathering, structure of a news report. 5W & 1H Lead: meaning, types question lead, suspended interest, quotation, non- traditional structure of a news report. Unit-III Concept and kinds of beat. Categories reporters-City, special correspondent, foreign correspondent, Stringer, Columnist, Functions & Responsibilities, follow-up story. Unit-IV Headlines: Meaning, Types, Importance of Headlines. Unit-V What is an interview, types of interview, interviewer & its qualities. Press conferences. Press release. 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I UNIT-I & II JOURNALISM - INTRODUCTION Journalism is the practice of investigating and reporting events, issues and trends to the mass audiences of print, broadcast and online media such as newspapers, magazines and books, radio and television stations and networks, and blogs and social and mobile media. The product generated by such activity is called journalism. People who gather and package news and information for mass dissemination are journalists. The field includes writing, editing, design and photography. With the idea in mind of informing the citizenry, journalists cover individuals, organizations, institutions, governments and businesses as well as cultural aspects of society such as arts and entertainment. News media are the main purveyors of information and opinion about public affairs. WHAT DOES A JOURNALIST DO? The main intention of those working in the journalism profession is to provide their readers and audiences with accurate, reliable information they need to function in society. -

Valuing Subjectivity in Journalism: Bias, Emotions, and Self-Interest As Tools in Arts Reporting

Original Article Journalism Valuing subjectivity in journalism: Bias, emotions, and self-interest as tools in arts reporting Phillipa Chong McMaster University, Canada Abstract This article examines the meanings and norms surrounding subjectivity across traditional and new forms of cultural journalism. While the ideal of objectivity is key to American journalism and its development as a profession, recent scholarship and new media developments have challenged the dominance of objectivity as a professional norm. This article begins with the understanding that subjectivity is an intractable part of knowing (and reporting on) the world around us to build our understanding of different modes of subjectivity and how these animate journalistic practices. Taking arts reporting, specifically reviewing, as a case study, the analysis draws on interviews with 40 book reviewers who write for major American newspapers, including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and prominent blogs. Findings reveal how emotions, bias, and self-interest are salient – sometimes as vice and sometimes as virtue – across the workflow of critics writing for traditional print outlets and book blogs and that these differences can be conceptualized as different epistemic styles. Keywords Blogs, emotion, literary journalism, newspapers, online media, practice, subjectivity/ objectivity Introduction Objectivity has long been the gold standard in American journalism and was key to its development into a profession (Benson and Neveu, 2005; Schudson, 1976). Yet Corresponding author: Phillipa Chong, Department of Sociology, McMaster University, 609 Kenneth Taylor Hall, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4M4, Canada. Email: [email protected] Chong 2 scholars have complicated the picture by pointing to the unattainability of objectivity as an ideal with some noting the increasing acceptance of subjectivity across different forms of journalism (Tumber and Prentoulis, 2003; Wahl-Jorgensen, 2012, 2013; Zelizer, 2009b). -

Telling Stories to a Different Beat: Photojournalism As a “Way of Life”

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Busst, Naomi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Naomi Verity Busst, BPhoto, MJ A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Bond University February 2012 Abstract This thesis presents a grounded theory of how photojournalism is a way of life. Some photojournalists dedicate themselves to telling other people's stories, documenting history and finding alternative ways to disseminate their work to audiences. Many self-fund their projects, not just for the love of the tradition, but also because they feel a sense of responsibility to tell stories that are at times outside the mainstream media’s focus. Some do this through necessity. While most photojournalism research has focused on photographers who are employed by media organisations, little, if any, has been undertaken concerning photojournalists who are freelancers.