Past Imperfect 2009 Final 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Civil War: the Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660'

H-Albion Roberts on Royle, 'The British Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660' Review published on Friday, April 1, 2005 Trevor Royle. The British Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. xviii + 888 pp. $40.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-312-29293-5. Reviewed by Stephen Roberts (History of Parliament Trust, London) Published on H-Albion (April, 2005) This is a large-scale treatment of a large-scale subject. The book is a narrative history of the disorders of the British archipelago, with an emphasis on the military conflicts. These are conventionally viewed as separate wars, and Trevor Royle divides his material in accordance with the convention. There are no fewer than forty-nine chapters in the book, with an epilogue, so inevitably the chapters are grouped into parts. Part 1 covers the build-up or as the author sees it, the "descent" to war, from 1638 to 1642, with proper emphasis on Charles I's disastrous policies in Scotland and Ireland. Part 2 takes us from the outbreak of the civil war in England to the king's engagement with the Scots, while the third part continues the story down to the conclusion of the third civil war, at Worcester in September 1651. Parts 4 and 5 deal with the transition from commonwealth to protectorate, and the restoration of the monarchy, respectively. In this choice of periodization, the book's main title, and its sub-title, lie a pointer to the varying focus of this work as a whole. -

“Houses and Families Continue by the Providence and Blessing of God”: Patriarchy and Authority in the British Civil Wars

“Houses and Families Continue by the Providence and Blessing of God”: Patriarchy and Authority in the British Civil Wars by Sara Siona Régnier-McKellar B.A., University of Ottawa, 2007 A Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History Sara Siona Régnier-McKellar, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60761-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60761-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. -

His Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Major-General

The New Model Army December 1646 Commander: His Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Major-General: Philip Skippon Lt General of Horse: Oliver Cromwell Lt General of the Ordnance: Thomas Hammond Commissary-General of Horse: Henry Ireton The Treasurers-at-War: Sir John Wollaston kt, Alderman Thomas Adams Esq, Alderman John Warner Esq, Alderman Thomas Andrews Esq, Alderman George Wytham Esq, Alderman Francis Allein Esq Abraham Chamberlain Esq John Dethick Esq Deputy-Treasurer-at-War: Captain John Blackwell Commissary General of Musters: Stane Deputy to the Commissary General of Musters: Mr James Standish Mr Richard Gerard Scoutmaster General: Major Leonard Watson Quartermaster-General of Foot: Spencer Assistant Quartermaster-General of Foot: Robert Wolsey Quartermaster-General of Horse: Major Richard Fincher Commissioners of Parliament residing with the Army: Colonel Pindar Colonel Thomas Herbert Captain Vincent Potter Harcourt Leighton Adjutant-Generals of Horse: Captain Christopher Flemming Captain Arthur Evelyn Adjutant-General of Foot: Lt Colonel James Grey Comptroller of the Ordnance: Captain Richard Deane Judge Advocate: John Mills Esq Secretary to the General and Soucil of War: John Rushworth Esq Chaplain to the Army: Master Bolles Commissary General of Victuals: Cowling Commissary General of Horse provisions: Jones Waggon-Master General: Master Richardson Physicians to the Army: Doctor Payne Doctor French Apothecary to the Army: Master Webb Surgeon to the General's Person: Master Winter Marshal-General of Foot: Captain Wykes Marshal-General -

Oblivion and Vengeance: Charles II Stuart's Policy Towards The

ARTICLES Paweł Kaptur 10.15290/cr.2016.14.3.04 Jan Kochanowski University, Kielce Oblivion and vengeance: Charles II Stuart’s policy towards the republicans at the Restoration of 1660 Abstract. The Restoration of Charles II Stuart in 1660 was reckoned in post-revolutionary England both in terms of a long-awaited relief and an inevitable menace. The return of the exiled prince, whose father’s disgraceful decapitation in the name of law eleven years earlier marked the end of the British monarchy, must have been looked forward to by those who expected rewards for their loyalty, inflexibility and royal affiliation in the turbulent times of the Inter- regnum. It must have been, however, feared by those who directly contributed to issuing the death warrant on the legally ruling king and to violating the irrefutable divine right of kings. Even though Charles II’s mercy was widely known, hardly anyone expected that the restored monarch’s inborn mildness would win over his well-grounded will to revenge his father’s death and the collapse of the British monarchy. It seems that Charles II was not exception- ally vindictive and was eager to show mercy and oblivion understood as an act of amnesty to those who sided with Cromwell and Parliament but did not contribute directly to the executioner raising his axe over the royal neck. On the other hand, the country’s unstable situation and the King’s newly-built reputation required some firm-handed actions taken by the sovereign in order to prevent further rebellions or plots in the future, and to strengthen the posi- tion of the monarchy so shattered by the Civil War and the Interregnum. -

A Study in Regicide . an Analysis of the Backgrounds and Opinions of the Twenty-Two Survivors of the '

A study in regicide; an analysis of the backgrounds and opinions of the twenty- two survivors of the High court of Justice Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kalish, Edward Melvyn, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 14:22:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318928 A STUDY IN REGICIDE . AN ANALYSIS OF THE BACKGROUNDS AND OPINIONS OF THE TWENTY-TWO SURVIVORS OF THE ' •: ; ■ HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE >' ' . by ' ' ■ Edward Ho Kalish A Thesis Submittedto the Faculty' of 'the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ' ' In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of : MASTER OF ARTS .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 3 STATEMENT:BY AUTHOR / This thesishas been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The - University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library« Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowedg- ment. of source is madeRequests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department .or the Dean of the Graduate<College-when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship«' ' In aliiotdiefV instanceshowever, permission . -

SKCM News the Magazine of the Society of King Charles the Martyr American Region Edition: December 2018

SKCM News The Magazine of the Society of King Charles the Martyr American Region Edition: December 2018 Charles I at Canterbury Cathedral Photo by Benjamin M. Guyer ‘Remember!’ WWW.SKCM-USA.ORG Table of Contents Society News 4 Obituary 5 Ordination and Consecration Anniversaries 7 Articles President’s Address The Rev’d Steven C. Rice 9 Sermon Remember! The Rev’d Gary Eichelberger 10 Texts and Studies Charles I’s 1646 Vow to Return Church Lands Introduced by Benjamin M. Guyer 13 Reports Annual Membership Report 17 Annual Financial Report 29 Membership Rosters (including Benefactors) 20 Societies of Interest 25 Board of Trustees 26 Contact Information 28 SKCM Goods List 29 3 Society News Upcoming Annual Masses New Members (continued) XXXVI Annual Mass: Nashotah House, Nashotah, WI, 26 January 2019. Garwood The Rev’d Fr Jason A. Hess, of Cobbs P. Anderson, PhD, Interim Dean/President. Creek, VA The Revd Alexander Pryor, Director of The Rev’d Scott Matthew Hoogerhyde, of St. Music, Worship & Residential Life. Louis, MO Thomas Edward Jacks, of Mandeville, LA XXXVII Annual Mass: St. Stephen’s Patricia Raeann Johnson, PhD, of Des Church, Providence, RI, 25 January 2020. Moines, IA The Revd Dr. John D. Alexander, Ph.D., Michael V. Jones, of Charleston, SC SSC, OL*, Rector. The Rev’d Kevin L. Morris, SCP, of Rockville Centre, NY (reinstated) XXXVIII Annual Mass: Trinity Church, The Rev’d David Radzik, of Seven Hills, OH Clarksville, TN, 30 January 2021. The Revd The Very Rev’d Dr. Steven G. Rindahl, Roger E. Senechal*, Chaplain, Tennessee FSAC, of Cibolo, TX Chapter. -

Views Strong Independents, And, Like Cromwell, Strove to Secure Soldiers of Similar Views to Fill Their Ranks

390 American Antiquarian Society. [April, MEMOIR OF MAJOE-GENEEAL THOMAS ÏÏAEE1S0N. BY CHARLES H. FIRTH. THOMAS HARRISON was a native of Newcastle-under-Lyme in the County of Staffordshire. His grandfather Richard Harrison was mayor of that borough in 1594 and 1608. His father, also named Richard, was four times mayor of his native town, viz. : in 1626, 1633, Í643 and 1648, and was an Alderman at the time of his death. Contemporary authorities agree in describing the second Richard Harrison as a butcher by trade, and the register of the parish church of Newcastle states that he was buried on March 25, 1653. The same register also records the burial of his widow " Mrs. Mary Harrison, of the Cross," on May 18, 1658. Thomas Harrison, the future regicide, was born in 1616. "Thomas Harrison filius Richardi, bapt. July 2"' is the entry in the baptismal register of the parish for the year. His father then resided in a house opposite to the Market- Cross, which was pulled down some years ago and replaced by shops. Of Thomas Harrison's early life little is known. He was probably educated at the grammar school of the town, or of some neighboring town. He does not appear to have been a member of either University. After leaving school he became clerk to an attorney, Thomas Houlker^ of Clif- 1 For all facts derived from the register of Newcastle-uncier-Lyme, and for all extracts from the records of the horough I am indebted to the kindness of Mr. Robert Fenton, çf Newcastle-under-Lyme. -

Cromwelliana

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 2017 The Cromwell Association President: Professor PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Vice Presidents: PAT BARNES Rt Hon FRANK DOBSON, PC Rt Hon STEPHEN DORRELL, PC Dr PATRICK LITTLE, PhD, FRHistS Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS Rt Hon the LORD NASEBY, PC Dr STEPHEN K. ROBERTS, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA Chairman: JOHN GOLDSMITH Honorary Secretary: JOHN NEWLAND Honorary Treasurer: GEOFFREY BUSH Membership Officer PAUL ROBBINS The Cromwell Association was formed in 1937 and is a registered charity (reg no. 1132954). The purpose of the Association is to advance the education of the public in both the life and legacy of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), politician, soldier and statesman, and the wider history of the seventeenth century. The Association seeks to progress its aims in the following ways: campaigns for the preservation and conservation of buildings and sites relevant to Cromwell commissions, on behalf of the Association, or in collaboration with others, plaques, panels and monuments at sites associated with Cromwell supports the Cromwell Museum and the Cromwell Collection in Huntingdon provides, within the competence of the Association, advice to the media on all matters relating to the period encourages interest in the period in all phases of formal education by the publication of reading lists, information and teachers’ guidance publishes news and information about the period, including an annual journal and regular newsletters organises an annual service, day schools, conferences, lectures, exhibitions and other educational events provides a web-based resource for researchers in the period including school students, genealogists and interested parties offers, from time to time grants, awards and prizes to individuals and organisations working towards the objectives stated above. -

Augustine Garland, a Well Known and Very Prosperous London Attorney, and His First Wife Ellen Whitteridge, Daughter of Jasper Whitteridge of London

GARLAND, AUGUSTINE (or Augustus) (born 1602, died subsequent to 1664), regicide and Parliamentary radical, MP 1648, 1654, 1659 (Queenborough), was the only son of Augustine Garland, a well known and very prosperous London attorney, and his first wife Ellen Whitteridge, daughter of Jasper Whitteridge of London. Garland was part French, his paternal grandmother having been a Frenchwoman of Calais. The Garlands had once been of Hayes in Kent (Visitation of London, 1634, I, 301). Garland was baptized at St. Antholin’s Budge Row, London, 13 January 1602. His father remarried Alice Johnson, widow, née Cliff (daughter of a London draper) 16 January 1604, at St. Dunstan’s, Stepney, Middlesex. Garland had one full sister and two half-sisters (all married). He was on bad terms with all of them as well as his father, according to his father’s will (P.C.C. Wills, Prob-11-176, p. 67), which was proved by one of the half-sisters on 27 January 1638. In the will, Garland is given less than any of the sisters (if their dowries are counted), palmed off with £550 and outlying houses and lands beyond London. These, however, were to be instrumental in Garland’s acquiring a political base, for he was to become MP for Queenborough in Kent, one of these locations (election writ issued 10 May 1648; CJ, V, 556a). Garland was admitted pensioner to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, at Easter, 1618. He later attended Cliffords Inn and then was admitted to Lincolns Inn 14 June 1631, contemporary with John Dixwell the regicide. He was called to the Bar 29 January 1639. -

Acceptance in Lieu Report 2013 Contents Preface Appendix 1 Sir Peter Bazalgette, Chair, Arts Council England 4 Cases Completed 2012/13 68

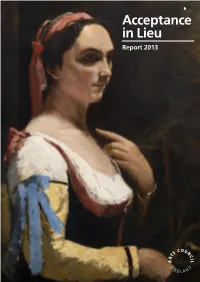

Back to contents Acceptance in Lieu Report 2013 Contents Preface Appendix 1 Sir Peter Bazalgette, Chair, Arts Council England 4 Cases completed 2012/13 68 Introduction Appendix 2 Edward Harley, Chairman of the Acceptance in 5 Members of the Acceptance in Lieu 69 Lieu Panel Panel during 2012/13 Government support for acquisitions 6 Appendix 3 Allocations 6 Expert advisers 2012/13 70 Archives 7 Additional funding 7 Appendix 4 Conditional Exemption 7 Permanent allocation of items reported in earlier 72 years but only decided in 2012/13 Acceptance in Lieu Panel membership 8 Cases 2012/13 1 Hepworth: two sculptures 11 2 Chattels from Knole 13 3 Raphael drawing 17 4 Objects relating to Captain Robert Falcon Scott RN 18 5 Chattels from Mount Stewart 19 6 The Hamilton-Rothschild tazza 23 7 The Westmorland of Apethorpe archive 25 8 George Stubbs: Equestrian Portrait of John Musters 26 9 Sir Peter Lely: Portrait of John and Sarah Earle 28 10 Sir Henry Raeburn: two portraits 30 11 Archive of the 4th Earl of Clarendon 32 12 Archive of the Acton family of Aldenham 33 13 Papers of Charles Darwin 34 14 Papers of Margaret Gatty and Juliana Ewing 35 15 Furniture from Chicheley Hall 36 16 Mark Rothko: watercolour 38 17 Alfred de Dreux: Portrait of Baron Lionel de Rothschild 41 18 Arts & Crafts collection 42 19 Nicolas Poussin: Extreme Unction 45 20 The Sir Denis Mahon collection of Guercino drawings 47 21 Two Qing dynasty Chinese ceramics 48 22 Two paintings by Johann Zoffany 51 23 Raphael Montañez Ortiz: two works from the 53 Destruction in Art Symposium 24 20th century studio pottery 54 25 Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: L'Italienne 55 Front cover: L‘Italienne by Jean-Baptiste 26 Edgar Degas: three sculptures 56 Camille Corot. -

The Political Consequences of King Charles II's Catholic Sympathies In

Tenor of Our Times Volume 6 Article 10 2017 The olitP ical Consequences of King Charles II's Catholic Sympathies in Restoration England Nathan C. Harkey Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Harkey, Nathan C. ( 2017) "The oP litical Consequences of King Charles II's Catholic Sympathies in Restoration England," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 6, Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol6/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES OF KING CHARLES II’S CATHOLIC SYMPATHIES IN RESTORATION ENGLAND By Nathan Harkey Religion now will serve no more To cloak our false professors; There’s none so blinde but plainly sees Who were the Lands Oppressors. – a pre-Restoration Royalist Propaganda rhyme1 In 1660, after spending over a decade in exile, Charles Stuart was invited back to the throne of England by a parliament that was filled with recently elected Royalists. He had spent his exile on mainland Europe, appealing to various other Royal powers to help him take back his kingdom. Fortunately for Charles, he was welcomed back by his people, who had for the most part suffered under a bland and morally strict regime following the execution of his father, Charles I. -

James Kirkton's History of the Covenanters Ralph Stewart

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 8 1989 A Gust of the North Wind: James Kirkton's History of the Covenanters Ralph Stewart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, Ralph (1989) "A Gust of the North Wind: James Kirkton's History of the Covenanters," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol24/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ralph Steu)art A Gust of the North Wind: |ames Kirkton's History of the Covenanters After the restoration of Charles II in 1660, the Presbyterian Church of Scofland was replaced with an Episcopalian one. Many ministers refused to accept the new regime, and were consequently expelled from their parishes and forbidden to preach. They and their supporters were known as Covenanters because they adhered to the principles of the Scottish "National Covenant" of 1638, according to which the church was largely independent of the state. The ministers who did continue preaching, in churches, houses, or out-of-doors "conventicles," faced increasingly heavy penalties. In 1670 the offence became capital, and after L675 the more notorious ministers were "intercommuned"-anyone associating with them faced the same penalties as the ministers; after 1678 any landowner on whose estate a conventicle had taken place, or a fugitive assisted, could be treated similarly.