A STATUS REPORT on GEMSTONES from AFGHANISTAN by Gary W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghazni of Afghanistan Issue: 2 Mohammad Towfiq Rahmani Month: October Miniature Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Herat University, Herat, Afghanistan

SHANLAX International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities s han lax # S I N C E 1 9 9 0 OPEN ACCESS Artistic Characters and Applied Materials of Buddhist Temples in Kabul Volume: 7 and Tapa Sardar (Sardar Hill) Ghazni of Afghanistan Issue: 2 Mohammad Towfiq Rahmani Month: October Miniature Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Herat University, Herat, Afghanistan Year: 2019 Abstract Kabul and Ghazni Buddhist Temple expresses Kushani Buddhist civilization in Afghanistan and also reflexes Buddhist religion’s thoughts at the era with acquisitive moves. The aim of this article P-ISSN: 2321-788X is introducing artistic characters of Kabul Buddhist temples and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni Buddhist Temple in which shows abroad effects of Buddhist religion in Afghanistan history and the importance of this issue is to determine characters of temple style with applied materials. The E-ISSN: 2582-0397 results of this research can present character of Buddhist Temples in Afghanistan, thoughts of establishment and artificial difference with applied materials. Received: 12.09.2019 Buddhist religion in Afghanistan penetrated and developed based on Mahayana religious thoughts. Artistic work of Kabul and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni Buddhist Temples are different from the point of artistic style and material applied; Bagram Artistic works are made in style of Garico Accepted: 19.09.2019 Buddhic and Garico Kushan but Tapa Narenj Hill artistic works are made based on Buddhist regulation and are seen as ethnical and Hellenistic style. There are similarities among Bagram Published: 01.10.2019 and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghani Buddhist Temples but most differentiates are set on statues in which Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni statue is lied in which is different from sit and stand still statues of Bagram. -

Red Glass for the Pharaoh Thilo Rehren

. ARCHAEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL HildO<heim, Genn•ny) '' excmting '� Red glass for the Pharaoh industrial estate dating to the foundatio period of the new city, including the larg-� I Thilo Rehren est known bronze foundries of antiquity,1 Glass in ancient Egypt appears to have been used as a substitute military workshops supplying and main for precious stones that were not available in the country. Here taining the pharaoh's chariotry including the process of glass manufacture is traced through the examina stables for hundreds of horses, and the only known production site for glass in tion of the fr agmentaryremains of ceramic reaction vessels and Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia. The crucibles used in the production of small glass ingots. excavations date back to the 1980s, but only in the past couple of years have we been able to identify the glassmaking evi n archaeological terms, glass is a these precious materials, and ancient Egypt dence, although much of it had been exca relatively young material that was is no exception to this rule. It was famous vated many years previously. Why this invented much later than pottery or for its riches in gold, but had no silver ores; delay? Because we didn't know how to rec Imetals; only from the beginning of it produced amethyst, carnelian and tur ognize glassmaking: there being no prece the Late Bronze Age onwards do we quoise, but not lapis lazuli, amber or ob dent or template to follow when looking have good evidence for its intentional and sidian. Should the country's rulers there for Bronze Age glassmaking, and the evi routine production. -

Mughal Warfare

1111 2 3 4 5111 Mughal Warfare 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 Mughal Warfare offers a much-needed new survey of the military history 4 of Mughal India during the age of imperial splendour from 1500 to 1700. 5 Jos Gommans looks at warfare as an integrated aspect of pre-colonial Indian 6 society. 7 Based on a vast range of primary sources from Europe and India, this 8 thorough study explores the wider geo-political, cultural and institutional 9 context of the Mughal military. Gommans also details practical and tech- 20111 nological aspects of combat, such as gunpowder technologies and the 1 animals used in battle. His comparative analysis throws new light on much- 2 contested theories of gunpowder empires and the spread of the military 3 revolution. 4 As the first original analysis of Mughal warfare for almost a century, this 5 will make essential reading for military specialists, students of military history 6 and general Asian history. 7 8 Jos Gommans teaches Indian history at the Kern Institute of Leiden 9 University in the Netherlands. His previous publications include The Rise 30111 of the Indo-Afghan Empire, 1710–1780 (1995) as well as numerous articles 1 on the medieval and early modern history of South Asia. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 40111 1 2 3 44111 1111 Warfare and History 2 General Editor 3 Jeremy Black 4 Professor of History, University of Exeter 5 6 Air Power in the Age of Total War The Soviet Military Experience 7 John Buckley Roger R. -

Rebuilding Afghanistan's Agriculture Sector

Rebuilding Afghanistan’s Agriculture Sector Asian Development Bank South Asia Department April 2003 © Asian Development Bank All rights reserved The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors of the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. Principal Author: Allan T. Kelly Supervisors: Frank Polman, Frederick C. Roche Coordinator: Craig Steffensen Editing and Typesetting: Sara Collins Medina Cover Design: Ram Cabrera Cover Photograph: Ian Gill/ADB Page photographs: Ian Gill/ADB Administrative Support: Wickie Baguisi, Jane Santiano Fulfillment: ADB Printing Unit The Asian Development Bank encourages use of the material presented herein, with appropriate credit. Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789 0980 Manila, Philippines Website: www.adb.org ISBN: 971-561-493-0 Publication Stock No. 040903 Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 Approach to Needs Assessment............................................................................................ 1 Sector Background ...............................................................................................................1 -

The Politics of Disarmament and Rearmament in Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ THE POLITICS OF DISARMAMENT AND REARMAMENT IN AFGHANISTAN Deedee Derksen ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines why internationally funded programs to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate militias since 2001 have not made Afghanistan more secure and why its society has instead become more militarized. Supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) as part of its broader program of study on the intersection of political, economic, and conflict dynamics in Afghanistan, the report is based on some 250 interviews with Afghan and Western officials, tribal leaders, villagers, Afghan National Security Force and militia commanders, and insurgent commanders and fighters, conducted primarily between 2011 and 2014. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Deedee Derksen has conducted research into Afghan militias since 2006. A former correspondent for the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, she has since 2011 pursued a PhD on the politics of disarmament and rearmament of militias at the War Studies Department of King’s College London. She is grateful to Patricia Gossman, Anatol Lieven, Mike Martin, Joanna Nathan, Scott Smith, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments and to everyone who agreed to be interviewed or helped in other ways. Cover photo: Former Taliban fighters line up to handover their rifles to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the pro- vincial governor’s compound. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. j. g. Joe Painter/RELEASED). Defense video and imagery dis- tribution system. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. -

Water Conflict Management and Cooperation Between Afghanistan and Pakistan

Journal of Hydrology 570 (2019) 875–892 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hydrology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol Research papers Water conflict management and cooperation between Afghanistan and T Pakistan ⁎ Said Shakib Atefa, , Fahima Sadeqinazhadb, Faisal Farjaadc, Devendra M. Amatyad a Founder and Transboundary Water Expert in Green Social Research Organization (GSRO), Kabul, Afghanistan b AZMA the Vocational Institute, Afghanistan c GSRO, Afghanistan d USDA Forest Service, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT This manuscript was handled by G. Syme, Managing water resource systems usually involves conflicts. Water recognizes no borders, defining the global Editor-in-Chief, with the assistance of Martina geopolitics of water conflicts, cooperation, negotiations, management, and resource development. Negotiations Aloisie Klimes, Associate Editor to develop mechanisms for two or more states to share an international watercourse involve complex networks of Keywords: natural, social and political system (Islam and Susskind, 2013). The Kabul River Basin presents unique cir- Water resources management cumstances for developing joint agreements for its utilization, rendering moot unproductive discussions of the Transboundary water management rights of upstream and downstream states based on principles of absolute territorial sovereignty or absolute Conflict resolution mechanism territorial integrity (McCaffrey, 2007). This paper analyses the different stages of water conflict transformation Afghanistan -

Reflective Index Reference Chart

REFLECTIVE INDEX REFERENCE CHART FOR PRESIDIUM DUO TESTER (PDT) Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Fluorite 16 - 18 1.434 - 1.434 Emerald 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Corundum 34 - 43 1.762 - 1.770 Opal 17 - 19 1.450 - 1.450 Verdite 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Idocrase 35 - 39 1.713 - 1.718 ? Glass 17 - 54 1.440 - 1.900 Brazilianite 27 - 32 1.602 - 1.621 Spinel 36 - 39 1.718 - 1.718 How does your Presidium tester Plastic 18 - 38 1.460 - 1.700 Rhodochrosite 27 - 48 1.597 - 1.817 TL Grossularite Garnet 36 - 40 1.720 - 1.720 Sodalite 19 - 21 1.483 - 1.483 Actinolite 28 - 33 1.614 - 1.642 Kyanite 36 - 41 1.716 - 1.731 work to get R.I. values? Lapis-lazuli 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Nephrite 28 - 33 1.606 - 1.632 Rhodonite 37 - 41 1.730 - 1.740 Reflective indices developed by Presidium can Moldavite 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Turquoise 28 - 34 1.610 - 1.650 TP Grossularite Garnet (Hessonite) 37 - 41 1.740 - 1.740 be matched in this table to the corresponding Obsidian 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Topaz (Blue, White) 29 - 32 1.619 - 1.627 Chrysoberyl (Alexandrite) 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.755 common Refractive Index values to get the Calcite 20 - 35 1.486 - 1.658 Danburite 29 - 33 1.630 - 1.636 Pyrope Garnet 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.746 R.I value of the gemstone. -

Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use

GUIDE TO THE WORLD’S TOP 20 MOST EFFECTIVE HEALING GEMSTONES FOR EVERYDAY USE BY ISABELLE MORTON Guide to the World’s Top 20 Most Effective Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use Copyright © 2019 by Isabelle Morton Photography by Ryan Morton, Isabelle Morton Cover photo by Jeff Skeirik All rights reserved. Published by The Gemstone Therapy Institute P.O. Box 4065 Manchester, Connecticut 06045 U.S.A. www.GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org IMPORTANT NOTICE This book is designed to provide information for purposes of reference and guidance and to accompany, not replace, the services of a qualified health care practitioner or physician. It is not the intent of the author or publisher to prescribe any substance or method to cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent any disease. In the event that you use this information with or without seeking medical attention, the author and publisher shall not be liable or otherwise responsible for any loss, damage, or injury directly or indirectly caused by or arising out of the information contained herein. CONTENTS Gemstones for Physical Healing Light Green Aventurine 5 Dark Green Aventurine 11 Malachite 17 Tree Agate 23 Gemstones for Emotional Healing Rhodonite 30 Morganite 36 Pink Chalcedony 43 Rose Quartz 49 Gemstones for Healing Memory, Patterns, & Habits Opalite 56 Leopardskin Jasper 62 Golden Beryl 68 Rhodocrosite 74 Gemstones for Healing the Mental Body Sodalite 81 Blue Lace Agate 87 Lapis Lazuli 93 Lavender Quartz 99 Gemstones to Nourish Your Spirit Amethyst 106 Clear Quartz / Frosted Quartz 112 Mother of Pearl 118 Gemstones For Physical Healing LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE DARK GREEN AVENTURINE MALACHITE TREE AGATE https://GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE 5 Copyright © 2019 Isabelle Morton. -

A World In-Between the Pre-Islamic Cultures of the Hindu Kush

Borders Itineraries on the Edges of Iran edited by Stefano Pellò A World In-between The Pre-Islamic Cultures of the Hindu Kush Augusto S. Cacopardo (Università degli Studi di Firenze, Italia) Abstract The vast mountain area stretching east of the Panjshir valley in Afghanistan to the bor- ders of Kashmir was, in pre-Islamic times, a homogenous culture area nested between the Iranian and the Indian worlds. Its inhabitants – speakers of a variety of Indo-European languages belonging mainly to the North-West-Indo-Aryan (or Dardic) and Nuristani groups – practiced related forms of polytheism differing in many traits but clearly united by a basic pastoral ideology encompassing all aspects of human life as well as the environment itself. The advance of Islam into the mountains, starting from the sixteenth century, gradually brought about the conversion of the whole area by the end of the nineteenth, with the sole exception of the Kalasha of Chitral who still practice their ancient religion to this day. Scholars who studied the area with a comparative approach focused mainly on the cultural traits connecting these cultures to India and especially to the Vedic world. Limited attention has been given to possible Iranian connections. The present article, on the basis of a recent in-depth investigation of the Kalasha ritual system, extends the comparison to other components and aspects of the Indian world, while providing at the same time some new data sug- gesting ancient Iranian influences. Summary 1 The Kafirs of the Hindu Kush and the Advance of Islam in the Mountains. – 2 Comparative Research in Peristan: the Indian World. -

13A Summary of the Panjsher Valley Emerald, Iron, and Silver Area of Interest

13A Summary of the Panjsher Valley Emerald, Iron, and Silver Area of Interest Contribution by Stephen G. Peters Abstract This chapter summarizes and interprets results from joint geologic and compilation activities conducted during 2009 to 2011 by the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations, and the Afghanistan Geological Survey in the Panjsher Valley emerald, iron, and silver area of interest (AOI) and subareas. The complementary chapters 13B and 13C address hyperspectral data and geohydrologic assessments, respectively, of the Panjsher Valley emerald, iron, and silver AOI. Additionally, supporting data for this chapter are available from the Afghanistan Ministry of Mines in Kabul. The emerald deposits of the Panjsher Valley are the main site for mining gemstone-grade emerald crystals in Afghanistan. The geology of the Panjsher Valley consists of Middle Paleozoic metamorphic rocks represented by a Silurian-Lower Carboniferous marble and Lower Carboniferous and Upper Carboniferous-Lower Permian terrigenous schist. Intrusive rocks include small bodies of gabbro diorite and quartz porphyry and a large intrusion of gneissic granite of the Laghman Complex. The area has an imbricate-block structure elongated to the southwest and northeast. Multiple tectonic events are related to structures within and parallel to the regional-scale Hari Rod fault system. Emerald mineralization in the Panjsher Valley AOI is genetically related to the Laghman Granitoid Complex and is controlled by elongated tectonic zones along the contacts between the carbonate and schist. The Panjsher Valley emerald district contains the following emerald occurrences from the west to east: Khinj, Mikeni I, Mikeni II, Rewat, and Darun. -

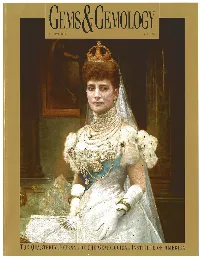

Fall 1993 Gems & Gemology

THEUUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE bEMOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA TABL OF CONTENTS 1993 Challenge Winners Letters FEATURE ARTICLE Jewels of the Edwardians Elise B. Misiorowski and Nancy 1Z. Hays A Prospectors' Guide Map to the Gem Deposits of Sri Lanka C. B. Dissanayuke and M.S. Rupasinghe Two Treated-Color Synthetic Red Diamonds Seen in the Trade Thomas M. Moses, llene Reinitz, Emmanuel Fritsch, and James E, Shigley Two Near-Colorless General Electric Type-IIa Synthetic Diamond Crystals James E. Shigley, Emmanuel Fritsch, and llene Reinitz REGULAR FEATURES Gem Trade Lab Notes Gem News Book Reviews Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: I. Snowman's circa-1910 portrait of Her Royal Highness Queen Alexandra, consort of King Edward VII of England, shows the plethora of iew- elry worn by ladies from the royal and wealthy upper classes of Europe and America at the turn of the 20th century. Alexandra's neck is wrapped with a pearl choker and many pearl necl<laces:the longest sautoir is pinned up in a swag effect using a pearl- and-diamond brooch. The gauzy tullle that decorates her ddcolletage is held in place by pins and brooches of every size and type, including a diamond star burst, a cres- cent, and two ruby-and-diamond bow brooches on either side of her neckline. Note the gold snake bracelet adorning her left wrist. The lead article in this issue exam- ines the styles, materials, and motifs of the elegant jewels favored by the distinctive group known as the Edwardians, who reigned as the leaders of high fashion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. -

Artist Jewellery Is Enjoying a Renaissance. Aimee Farrell Looks At

Artist jewellery Right: Catherine Deneuve wearing Man Ray’s Pendantif-Pendant earrings in a photo by the artist, 1968. Below: Georges Braque’s Circé, 1962 brooch Photo: Sotheby’s France/ArtDigital Studio © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017; Braque jewellery courtesy Diane Venet; all other jewellery shown here © Louisa Guinness Gallery Frame the face Artist jewellery is enjoying a renaissance. Aimee Farrell looks at its most captivating – and collectible – creations, from May Ray’s mega earrings to Georges Braque’s brooches 16 Fashion has long been in thrall of artist jewellery. In the 1930s, couturier Elsa Schiaparelli commissioned her circle of artist friends including Jean Cocteau and Alberto Giacometti to create experimental jewels for her collections; art world fashion plate Peggy Guggenheim boasted of being the only woman to Clockwise from left: wear the “enormous mobile earrings” conceived Man Ray’s La Jolie, 1970 pendant with lapis; The by kinetic artist Alexander Calder; and Yves Saint Oculist, 1971 brooch Laurent, a generous patron of the French husband- in gold and malachite; and his photograph of and-wife artist duo “Les Lalannes” summoned Claude Nancy Cunard, 1926 © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Lalanne to conjure a series of bronze breast plates, Paris and DACS, London akin to armour, for his dramatic autumn/winter 2017; Telimage, 2017 1969 show. So when Maria Grazia Chiuri enlisted Lalanne, now in her nineties, to devise the sculptural copper Man Ray jewels for her botanical-themed Christian Dior A brooch portraying Lee Miller’s lips, rings complete with tiny Couture debut this year, she put artist jewellery firmly tunnels that offer an alternative perspective on the world and 24 carat gold sunglasses – it’s no surprise that the avant-garde back on the agenda.