Bumblebee Talks and Walks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teen Facilitator Guide Created By

2016 Teen Facilitator Guide Created by: Robert L. Horton, PhD, Agri-Science Professor, College of Food, Agriculture, and Environmental Sciences, The Ohio State University Patty House, MS, County Extension Educator 3, College of Food, Agriculture, and Environmental Sciences, The Ohio State University Denise Ellsworth, Program Director, Honey Bee and Native Pollinator Education, The Ohio State University Denise M. Johnson, Program Manager, Ohio State University Extension Master Gardener Volunteer Program, The Ohio State University Margaret Duden, SimplySmart Education Specialists Liz Kasper, Pete Sandvik, Northern Design Group The 4-H Ag Innovators Experience Honey Bee Challenge focuses on a critical component—honey bees—to growing food and feeding the world. Approximately one in every three bites we eat is the result of these pollinators at work. Apples, pumpkins, strawberries, alfalfa, sunflowers, oranges, buckwheat, and almonds are just some of the crops that rely on honey bee pollination. As the Teen Facilitator for this activity, you will help youth learn that: • Honey bees and other pollinators are essential contributors to growing food and feeding the world. • Honey bees utilize a combination of natural and agricultural habitats to maintain healthy hives. • Preserving and maintaining the natural foraging habitats of honey bees is important. • Commercial beekeepers transport honey bees all across the country to boost crop yield, since there is not enough managed honeybees or native pollinators to maximize agricultural production. • Youth can contribute to honey bee health in their own communities. The 4-H Ag Innovators Honey Bee Challenge is an ideal activity for 3rd to 8th grade youth at summer reading programs, summer camps, summer childcare settings, festivals, and fairs. -

Bee Bodies Honey Bee Anatomy

BEE BODIES HONEY BEE ANATOMY Essential Question: HOW DOES A HONEY BEE’S STRUCTURE SUPPORT ITS FUNCTION IN THE ECOSYSTEM? LEARNING OBJECTIVES n Distinguish between the structural and behavioral adaptations of the honey bee. n Investigate and infer the function of basic adaptations. n Explain how different organisms use their unique adaptations to meet their needs. RESOURCES MATERIALS • Image, Bee Pollen Baskets • Chart Paper • Writing Utensils • Image, Bee Body • Markers • Reading, Bee Bodies • Journals, Paper, or Digital • Assessment, Which Bee Notebooks Body Part? OVERVIEW OF LESSON / BACKGROUND Most people can describe or draw a basic bee: black and yellow stripes, wings, a 3-part body. This lesson will take students beyond the basics by bringing the honey bee’s amazing anatomy and structures alive. From the pollen basket to the hairy eyes, bees are creatures that inspire wonder and curiosity. Although each of the 20,000 species of bees in the world has something in common with the next, this lesson focuses on honey bees: the only insects that produce food for humans. In order to survive, thrive, and perform their work in the world, honey bees have evolved with a fascinating anatomy and specific adaptations. This detailed, up-close look at both the structures and the functions of honey bee anatomy will help students understand the bee’s place in the world. Honey bees have many parts that are easily recognizable: a head, thorax, abdomen, legs, antennae, eyes, wings, etc. They also have a corbiculae (or pollen basket), tiny hairs on their eyes, a proboscis, and hooks (or hamuli) that hold their wings together in flight. -

The Role and Significance of Stingless Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes: Meliponini) in the Natural Environment

Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Vol. 30 No 2(80): 1-5 Ochrona Środowiska i Zasobów Naturalnych DOI 10.2478/oszn-2019-0005 Jolanta Bąk-Badowska*, Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska*, Barbara Gworek**, Wanda Kacprzyk***, Jarosław Chmielewski**** The role and significance of stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes: Meliponini) in the natural environment * Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, ** Warsaw University of Life Sciences, *** Institute of Environmental Protection-National Research Institute, **** Wyższa Szkoła Rehabilitacji w Warszawie; e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Stingless bees, biology, ecology, economic significance Abstract This article refers to the biology and ecology of stingless bees (Meliponini), living in tropical and subtropical areas. Similar to honey bees (Apis mellifera), stingless bees (Meliponini) belong to the category of proper social insects and are at the highest level of social development. This group of insects comprises about 500 species and they are the most common bees pollinating the native plants in many tropical areas. Families of stingless bees are usually quite numerous, reaching up to 100,000 individuals. They are characterised by polymorphism, age polyethism and perennialism. This article presents the structural complexity of natural nesting of these tropical insects and their ability to settle in artificial nest traps. The main significance of stingless bees for humans is their role in the natural environment as pollinators, which is an essential factor influencing biodiversity. © IOŚ-PIB 1. INTRODUCTION Ctenoplectridae). Similarly, as in Europe, representatives Bees (Apiformes) represent a very important element of 6 families occur in Poland: Colletidae, Andrenidae, influencing biodiversity; as active pollinators. They play Halictidae, Melittidae, Megachilidae and Apidae; the latter a key role in maintaining the species richness of many includes the Anthophoridae. -

Common Pollinators of British Columbia – a Visual Identification

COMMON POLLINATORS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA A Visual Identification Guide Created by Border Free Bees and the Environmental Youth Alliance 1 · Navigation Honey Bee Bumble Bee Other Bees Hover Fly Butterfly Wasp Navigation 2 Introduction 3 Insight Citizen Science 3 Basic Insect Anatomy Pollinator Categories 4 Honey Bee 8 Bumble Bee 12 Other Bees 20 Hover Fly 24 Butterfly 28 Wasp 31 Complimentary Resources 32 Acknowledgments 33 Field Notes Introduction This visual guide was created to help as a field guide to use in comparing educate the public on how to identify closely similar species. Rather, treat common pollinators in British Columbia. this guide as a visual aid to direct your Bees are by far the most representative skills towards different families of group, and critically important bees and general characteristics you to providing pollination service to may be able to see while outdoors. terrestrial ecosystems and agricultural The guide breaks pollinators down landscapes. They effectively transfer into 6 categories: Honey Bees, Bumble pollen with feather-like hairs on their Bees, Other Bees, Wasps, Hover Flies and bodies capturing pollen grains. It is Butterflies. With a basic understanding estimated that there are around 500 of the characteristics that differentiate species of bees in British Columbia. these types of pollinators you can This guide serves as an introduction to participate in pollinator citizen science the common groups of pollinators that programs with ease. you may observe, and does not stand Basic Insect Anatomy Antenna Proboscis (tongue) Compound Eye Insight is a mobile app created by Border Free Bees that Thorax makes it easy for citizens to record pollinator observations Forewing using their smart phones. -

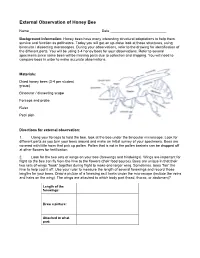

External Observation of Honey Bee

External Observation of Honey Bee Name ___________________________________ Date ____________________________ Background Information: Honey bees have many interesting structural adaptations to help them survive and function as pollinators. Today you will get an up-close look at those structures, using binocular / dissecting microscopes. During your observations, refer to the drawing for identification of the different parts. You will be using 3-4 honey bees for your observations. Refer to several specimens since some bees will be missing parts due to collection and shipping. You will need to compare bees in order to make accurate observations. Materials: Dried honey bees (3-4 per student group) Binocular / dissecting scope Forceps and probe Ruler Petri dish Directions for external observation: 1. Using your forceps to hold the bee, look at the bee under the binocular microscope. Look for different parts as you turn your bees around and make an initial survey of your specimens. Bees are covered with little hairs that pick up pollen. Pollen that is not in the pollen baskets can be dropped off at other flowers for fertilization. 2. Look for the two sets of wings on your bee (forewings and hindwings). Wings are important for flight so the bee can fly from the hive to the flowers (their food source). Bees are unique in that their two sets of wings “hook” together during flight to make one larger wing. Sometimes, bees “fan” the hive to help cool it off. Use your ruler to measure the length of several forewings and record those lengths for your bees. Draw a picture of a forewing as it looks under the microscope (include the veins and hairs on the wing). -

Quick Facts Feeding Honey Bees in Colorado

Feeding Honey Bees In Colorado Fact Sheet 5.622 Insect Series | Home & Garden By Arathi Seshadri, Catherine Mills & Kurt Jones* Quick Facts Healthy bees, like all living organisms, warm during cold winter days. Honey bees Dietary needs of bees are require a regular supply of food and water. do not hibernate but instead form a tight complex because they While they are known for their love of nectar cluster where the bees vibrate their wing need nectar and pollen and pollen from flowers, the dietary needs muscles and shiver to generate warmth on from a variety of different of bees are much more complex because the coldest of winter days. This requires a lot plants. they need nectar and pollen from a variety of carbohydrates and therefore it is important of different plants. Nectar from flowers and for the colony to have adequate stored Pollen and nectar are honey and access to sugar solution to make stored honey provide the carbohydrates for the source of protein it through the cold winters in Colorado. honey bees. Pollen provides the protein, and carbohydrates for lipids, vitamins and mineral components of the developing brood the honey bee diet. Water is provided to the Seasonal Differences in Feeding colony through metabolism of nectar and Honey bee colonies are active and in the hive. Nutritional honey, and through collection by foragers. growing in the spring and summer seasons. requirements for a honey Fresh water should be provided whenever In the winter season, the colonies do not bee colony changes foraging bees are observed outside the hive. -

Beekeeping Glossary of Terms

Office of Continuing Professional Education www.cpe.rutgers.edu New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station [email protected] Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 102 Ryders Lane 848-932-9271 New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8519 Fax: 732-932-1187 Bee-ginner’s Beekeeping: Glossary of Terms This "Glossary of Terms” is available for your review so that you can familiarize yourself with beekeeping terminology before the start of class. Visit www.cpe.rutgers.edu/bees to learn more about our Beekeeping programs. A • Abdomen - the posterior or third region of the body of a bee enclosing the honey stomach, true stomach, intestine, sting, and reproductive organs. • Absconding swarm - an entire colony of bees that abandons the hive because of disease, wax moth, or other maladies. • Adulterated honey - any product labeled “Honey” or “Pure Honey” that contains ingredients other than honey but does not show these on the label. (Suspected mislabeling should be reported to the Food and Drug Administration.) • After swarm - a small swarm, usually headed by a virgin queen, which may leave the hive after the first or prime swarm has departed. • Alighting board - a small projection or platform at the entrance of the hive. • American foulbrood - a brood disease of honey bees caused by the spore-forming bacterium, Bacillus larvae. • Anaphylactic shock - constriction of the muscles surrounding the bronchial tubes of a human, caused by hypersensitivity to venom and resulting in sudden death unless immediate medical attention is received. • Apiary - colonies, hives, and other equipment assembled in one location for beekeeping operations; bee yard. • Apiculture - the science and art of raising honey bees. -

Montana Bee Identification Guide Casey M

Montana Bee Identification Guide Casey M. Delphia1, Kevin M. O’Neill1, and Scott Prajzner2 1Department of Land Resources & Environmental Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 2Department of Entomology, Ohio State University OARDC, Wooster, OH In cooperation with Pollinator Partnership Bees play an important role in natural and agricultural systems as pollinators of flowering plants that provide food, fiber, animal forage, and ecological services like soil and water conservation. In fact, approximately three-quarters of all flowering plants rely on pollinators to reproduce. In addition to honey Casey M Delphia ©2008 RKD Peterson ©2008 bees, native bees provide valuable pollination Lynette ©2010 Schimming ©2011 services. Though unknown, the number of native bee RKD Peterson ©2007 Bumble bees (Bombus spp.) species in Montana is likely in the hundreds. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) Family: Apidae. Robust, hairy bees; black body covered This guide provides information for identifying 10 with black, yellow, orange, or white hairs in bands; Family: Apidae. Heart-shaped head; hairy eyes; black to types of bees commonly found in Montana including pollen basket on hind legs; 10-23 mm. descriptions of key characters, size (mm), nesting amber-brown body with pale and dark stripes on habitat, and other identifying behaviors. abdomen; barrel-shaped abdomen; pollen basket on • Social colonies; often nest underground in small hind legs; 10-15mm. cavities like old rodent burrows. Bee Identification • Bumble bees can buzz-pollinate, which is important • Social colonies; live in man-made hives and natural for plants that require vibration to release pollen. Bees, like other insects, have three body segments: a cavities like tree holes; swarm to locate new nests. -

Ohio Bee Guide

Ohio Bee Identification Guide Developed by Scott Prajzner and Mary Gardiner, Department of Entomology, Ohio State University OARDC, Wooster, OH in cooperation with Pollinator Partnership Bees are beneficial insects that pollinate flowering plants by transferring pollen from one flower to another. This is important for plant reproduction and food production. In fact, pollinators are responsible for 1 out of every 3 bites of Race Matteson K. food you take. While the honey bee gets most of the credit Matteson for providing pollination, there are actually about 500 bee ©Kevin ©Donna species in Ohio! ©OhWeh 8‐21mm ©Kevin Honey bee (Apis mellifera) 12‐15mm Bumble bee (Bombus spp.) Using this guide: This card provides key features Light to dark brown body with pale and dark hairs in Black body, extensively covered with black and needed to identify 10 types of bees found in home bands on abdomen. Pollen basket present. Abdomen yellow hairs on all body segments. Pollen basket landscapes. The approximate size of each bee is listed in barrel‐shaped. Head heart‐shaped. present. Robust body. Long face. millimeters. The following symbols will help along the way: Colonies nest in man‐made hives, in the open, Colonies nest underground, commonly in old Common nesting locations. and in cavities. Swarm to locate new nest. rodent burrows. Identifying behaviors to watch for. Honey bees have hairy eyes! Bumble bees pollinate in cool, cloudy weather when most bees are at home! Additional ID features that may be seen with the aid of a hand lens. Lépinay How to Identify Bees ‐ Russo ©Shyamal Kropiewnicki All bees have three body segments, ©Jodelet ©Ted a head, thorax, and abdomen. -

Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide

Pennsylvania Native Bee Survey Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide Revised for Pennsylvania By: Leo Donovall and Dennis vanEngelsdorp Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture The Pennsylvania State University Based on the “California Pollinator Project: Citizen Scientist Pollinator Monitoring Guide” Developed By: Katharina Ullmann, Tiffany Shih, Mace Vaughan, and Claire Kremen The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation University of California at Berkeley The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is an international, nonprofit, member-supported organization dedicated to preserving wildlife and its habitat through the conservation of invertebrates. The Society promotes protection of invertebrates and their habitat through science-based advocacy, conservation, and education projects. Its work focuses on three principal areas – endangered species, watershed health, and pollinator conservation. For more information about the Society or on becoming a member, please visit our website (www.xerces.org) or call us at (503) 232-6639. Through its pollinator conservation program, the Society offers practical advice and technical support on habitat management for native pollinator insects. University of California Berkeley collaborates with the Xerces Society on monitoring pollinator communities and pollination function at farm sites before and after restoration. University of California Berkeley conducts studies to calibrate the observational data collected by citizen scientists against the specimen-based data collected by scientists -

What Makes a Good Pollinator? Why Is Pollen Sticky?

What makes a good pollinator? Dependence on flowers for food o Bees aren’t trying to be good pollinators. They are visiting flowers to gather food and in the process come into contact with pollen grains. Their attraction to flowers is part of what makes them a good pollinator. Hairy bodies and pollen carrying structures o Bees generally have hairy bodies that trap pollen grains. As they move from flower to flower, some of it brushes off. Some bees even have a special structure called a corbicula (a pollen basket), which is used to collect and carry large quantities to their home. Floral fidelity (Visiting flowers from the same plant species) o When bees find a valuable food resource, they tend to forage on that species exclusively until it is gone. This means more pollen is being transported to the same plant species for cross-pollination. Why is pollen sticky? Wind-pollinated plants produce lots of lightweight, smooth pollen. However, insect-pollinated plants don’t produce as much pollen and the pollen is heavy and sticky. When an insect visits a flower for food, the pollen gets caught in hairs for easy transport to another flower. What insect body parts or structures make Dandelion pollen pollination possible? Pollinators use their eyes and antennae (sense of smell) to locate flowers (usually ones with bright colors that smell). Wings or legs allow pollinators to move easily from flower to flower, taking pollen along with them. Many bees are also great pollinators because they have hairy bodies. Pollen gets caught in these hairs and drops off on other flowers they visit. -

Collection and Identification of Pollen from Honey Bee Colonies

Collection and Identification of Pollen from Honey Bee Colonies Ellen Topitzhofer1, Hannah Lucas1, Emily Carlson1, Priyadarshini Chakrabarti1, Ramesh Sagili1 1 Department of Horticulture, Oregon State University Corresponding Author Abstract Ramesh Sagili [email protected] Researchers often collect and analyze corbicular pollen from honey bees to identify the plant sources on which they forage for pollen or to estimate pesticide exposure of Citation bees via pollen. Described herein is an effective pollen-trapping method for collecting Topitzhofer, E., Lucas, H., Carlson, E., corbicular pollen from honey bees returning to their hives. This collection method Chakrabarti, P., Sagili, R. Collection and Identification of Pollen from Honey Bee results in large quantities of corbicular pollen that can be used for research purposes. Colonies. J. Vis. Exp. (167), e62064, Honey bees collect pollen from many plant species, but typically visit one species doi:10.3791/62064 (2021). during each collection trip. Therefore, each corbicular pollen pellet predominantly Date Published represents one plant species, and each pollen pellet can be described by color. This January 19, 2021 allows the sorting of samples of corbicular pollen by color to segregate plant sources. Researchers can further classify corbicular pollen by analyzing the morphology of DOI acetolyzed pollen grains for taxonomic identification. These methods are commonly 10.3791/62064 used in studies related to pollinators such as pollination efficiency, pollinator foraging dynamics, diet quality, and diversity. Detailed methodologies are presented for URL collecting corbicular pollen using pollen traps, sorting pollen by color, and acetolyzing jove.com/video/62064 pollen grains. Also presented are results pertaining to the frequency of pellet colors and taxa of corbicular pollen collected from honey bees in five different cropping systems.