08-1448 Brown V. Entertainment Merchants Assn. (06/27/2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Violence Do Children Have Too Much Access to Violent Content?

Published by CQ Press, an Imprint of SAGE Publications, Inc. www.cqresearcher.com media violence Do children have too much access to violent content? ecent accounts of mass school shootings and other violence have intensified the debate about whether pervasive violence in movies, television and video R games negatively influences young people’s behavior. Over the past century, the question has led the entertain ment media to voluntarily create viewing guidelines and launch public awareness campaigns to help parents and other consumers make appropriate choices. But lawmakers’ attempts to restrict or ban con - tent have been unsuccessful because courts repeatedly have upheld The ultraviolent video game “Grand Theft Auto V” the industry’s right to free speech. In the wake of a 2011 Supreme grossed more than $1 billion in its first three days on the market. Young players know it’s fantasy, Court ruling that said a direct causal link between media violence some experts say, but others warn the game can negatively influence youths’ behavior. — particularly video games — and real violence has not been proved, the Obama administration has called for more research into the question. media and video game executives say the cause of mas shootings is multifaceted and c annot be blamed on the enter - I tainment industry, but many researchers and lawmakers say the THIS REPORT N industry should shoulder some responsibility. THE ISSUES ....................147 S BACKGROUND ................153 I CHRONOLOGY ................155 D CURRENT SITUATION ........158 E CQ Researcher • Feb. 14, 2014 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ........................161 Volume 24, Number 7 • Pages 145-168 OUTLOOK ......................162 RECIPIENT Of SOCIETY Of PROfESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AwARD fOR BIBLIOGRAPHY ................166 EXCELLENCE N AmERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILvER GAvEL AwARD THE NEXT STEP ..............167 mEDIA vIOLENCE Feb. -

Download This PDF File

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 March 2013 Vol. LXII No. 2 www.ala.org/nif Filtering continues to be an important issue for most schools around the country. That was the message of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), a division of the American Library Association, national longitudinal survey, School Libraries Count!, conducted between January 24 and March 4, 2012. The annual sur- vey collected data on filtering based on responses to fourteen questions ranging from whether or not their schools use filters, to the specific types of social media blocked at their schools. AASL survey The survey data suggests that many schools are going beyond the requirements set forth by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in its Child Internet Protection explores Act (CIPA). When asked whether their schools or districts filter online content, 98% of the respon- dents said content is filtered. Specific types of filtering were also listed in the survey, filtering encouraging respondents to check any filtering that applied at their schools. There were in schools 4,299 responses with the following results: • 94% (4,041) Use filtering software • 87% (3,740) Have an acceptable use policy (AUP) • 73% (3,138) Supervise the students while accessing the Internet • 27% (1,174) Limit access to the Internet • 8% (343) Allow student access to the Internet on a case-by-case basis The data indicates that the majority of respondents do use filtering software, but also work through an AUP with students, or supervise student use of online content individually. -

Unified Communications Comparison Guide

Unified Communications Comparison Guide Ziff Davis February 2014 Unified Communications (UC) is a useful solution for busy people to collaborate more effectively both within and outside their organizations. This guide provides a side-by-side comparison of the top 10 Unified Communications platforms based on the most common features and functions. Ziff Davis ©2014 Business UC Criteria Directory Mobile Contact Vendor/Product Product Focus Price IM/Presence eDiscovery Multi-party Cloud On-premesis Integration Support Groups SOHO, Lync SMB, $$$ Enterprise SMB, Jabber n/a Enterprise SMB, MiCollab n/a Enterprise SOHO, Open Touch n/a SMB SOHO, Aura SMB, n/a Enterprise SOHO, UC SMB, n/a Enterprise SOHO, Univerge 3C SMB, n/a Enterprise SMB, Sametime $ Enterprise SOHO, SMB, n/a Enterprise SOHO, Sky SMB, $$$$ Communicator Enterprise $ = $1-10/user $$ = $11-20/user $$$ =$21-30/user $$$ =$31-39/user Ziff Davis / Comparison Guide / Unified Communications Ziff Davis ©2014 2 Footnotes About VoIP-News.com VoIP News is a long-running news and information publication covering all aspects of the VoIP and Internet Telephony marketplaces. It is owned by Ziff Davis, Inc and is the premier source worldwide for business VoIP information. The site provides original content covering news, events and background information in the VoIP market. It has strong relationships with members of the VoIP community and is rapidly building a unique, high-quality community of VoIP users and vendors. About Ziff Davis Ziff Davis, Inc. is the leading digital media company specializing in the technology, gaming and men’s lifestyle categories, reaching over 117 million unique visitors per month. -

Research Proposal – Overview of the Literature

EXPOSURE TO VIOLENT AND PROSOCIAL VIDEO GAMES: EFFECTS ON HOSTILE ATTRIBUTION BIAS, AGGRESSION, AGGRESSIVE DRIVING TENDENCIES, AND EMPATHY by Jason A. Middleton, Bachelor of Arts (Honours), York University, 2007 A thesis presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Psychology Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2014 © Jason A. Middleton 2014 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Exposure to Violent and Prosocial Video Games: Effects on Hostile Attribution Bias, Aggression, Aggressive Driving Tendencies, and Empathy Jason A. Middleton Master of Arts in Psychology, 2014, Ryerson University Abstract The present study aimed to investigate the possible relation between reported video game play (i.e., violent, aggressive driving, and prosocial types) and four outcomes of social behaviour: hostile attribution bias, aggression, aggressive driving tendencies, and empathy. A sample of 136 university students (67 males and 69 females), age 17 to 58 (M = 20.66), completed various self-report measures. Data were analyzed both in terms of the whole sample and separately according to participant sex. -

The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya: Manga V

THE MELANCHOLY OF HARUHI SUZUMIYA: MANGA V. 17 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nagaru Tanigawa,Gaku Tsugano,Noizi Ito | 176 pages | 17 Dec 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316322348 | English | New York, United States The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya: Manga v. 17 PDF Book The two series were streamed in Japanese and with English subtitles on Kadokawa's YouTube channel between February 13 and May 15, Character Family see all. Chad rated it liked it Nov 10, Essential We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. While Haruhi is the central character to the plot, the story is told from the point of view of Kyon , one of Haruhi's classmates. Retrieved February 26, On April 17, Yen Press announced that they had acquired the license for the North American release of the first four volumes of the second manga series, promising the manga would not be censored. September 25, August 21, [10] [35]. No trivia or quizzes yet. The "next episode" previews feature two different episode numberings: one number from Haruhi, who numbers the episodes in chronological order, and one number from Kyon, who numbered them in broadcast order. Nagaru Tanigawa is a Japanese author best known for The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya for which he won the grand prize at the eighth annual Sneaker Awards. November 21, [41]. Era see all. Nineteen Eighty-four by George Orwell Paperback, 4. Retrieved April 14, The series has been licensed by Bandai Entertainment and has been dubbed by Bang Zoom! An omnibus of three anthologies containing short stories from several different manga artists. -

Something Is Rotten in the State of Aggression Research

SOMETHING IS ROTTEN IN THE STATE OF AGGRESSION RESEARCH: NOVEL METHODOLOGICAL AND THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO RESEARCH ON DIGITAL GAMES AND HUMAN AGGRESSION Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln nach der Promotionsordnung vom 10.05.2010 vorgelegt von Malte Elson aus Köln 9. April 2014 Diese Dissertation wurde von der Humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln im Juli 2014 angenommen. I can’t believe schools are still teaching kids about the null hypothesis. I remember reading a big study that conclusively disproved it years ago. - Randall Munroe, xkcd Acknowledgments For always helping me to make the right decisions, I thank Natalie, my (highly) significant other. And I’m in debt to my parents for unconditionally supporting me when I made the wrong ones. I thank Johannes, my partner in crime, for keeping our research on course, and offering adequate distraction from it whenever necessary. I was truly lucky to have my two supervisors, Prof. Dr. Gary Bente and Prof. Dr. Christopher Ferguson, who allowed me all the freedom in the world in my research adventure, but always offered guidance whenever I wandered off (on side quests). None of this would have been possible, of course, without my boss, Thorsten, who paid not only for my bread and butter, but also for many studies, conference trips, and other events that gave me the opportunity to make new friends abroad (looking at you, Jimmy). And, of course, I want to express my gratitude to Julia, who became my “academic nanny” when legal complications hampered my full adoption. -

United Kingdom in Re Struthers and Others V. Japan

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Decision of 30 November 1960 in the case United Kingdom in re Struthers and others v. Japan Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Décision du 30 novembre 1960 dans l’affaire Royaume-Uni in re Struthers et al. c. Japon 30 November 1960 VOLUME XXIX, pp.513-519 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2012 PART XXIII Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le Gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Decision of 30 November 1960 in the case United Kingdom in re Struthers and others v. Japan* Décision du 30 novembre 1960 dans l’affaire Royaume-Uni in re Struthers et al. c. Japon** Treaty of peace between the United Kingdom and Japan of 1951—treaty interpre- tation—intention of the parties—meaning of “property”—inability of States to restrict treaty obligations through national law. -

Henry V Plays Richard II

Colby Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 2 June Article 6 June 1990 "I will...Be like a king": Henry V Plays Richard II Barbara H. Traister Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 26, no.2, June 1990, p.112-121 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Traister: "I will...Be like a king": Henry V Plays Richard II "I will . .. Be like a king": Henry V Plays Richard II by BARBARA H. TRAISTER N BOTH RichardII and Henry v, the first and last plays ofthe second tetralogy, I kings engage in highly theatrical activity. Each play, however, has a very different metadramatic focus. In Richard II acting becomes a metaphor for the way Richard sees himself. The focus of audience attention is the narcissistic royal actor whose principal concern is his own posturing and who is his own greatest, and eventually only, admirer. Richard is an actor and dramatist, the embodiment of Elizabeth I's comment: "We Princes, I tell you, are set on stages, in the sight and view of all the world duly observed" (quoted in Neale 1957,2:19). However, his self-ab sorption and blindness to the world around him lead the audience to make few, if any, connections between him and the actor-dramatist who created him. The play is nearly empty of self-reflexive dramatic overtones despite its complex portrait of a player king. -

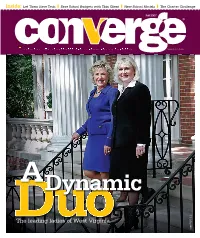

Social Networking for Educators — by Marina Leight and Cathilea Robinett Classroom Resources and Professional Development Are Reasons to Log On

inside: Let Them Have Tech | Save School Budgets with Thin Client | New School Models | The Charter Challenge Fall 2007 » STRATEGY AND LEADERSHIP FOR TECHNOLOGY IN EDUCATION A publication of e.Republic ADynamic DuoThe leading ladies of West Virginia. Issue 4 | Vol.2 CCON10_01.inddON10_01.indd 1100 110/4/070/4/07 11:57:17:57:17 PPMM 100 Blue Ravine Road Folsom, CA. 95630 _______ Designer _______ Creative Dir. 916-932-1300 Pg Cyan Magenta Yellow Black ® _______ Editorial _______ Prepress 5 25 50 75 95 100 5 25 50 75 95 100 5 25 50 75 95 100 5 25 50 75 95 100 _________ Production _______ OK to go Students not quite spellbound in class? A projector from CDW•G can liven up the room a bit. Epson PowerLite® S5 • 2000 ANSI lumens SVGA projector $ 99 • Lightweight, travel-friendly design — weighs only 5.8 lbs. 599 • Energy-efficient E-TORL lamp lasts up to 4000 hours CDWG 1225649 • Two-year limited parts and labor, 90-day lamp warranty with Epson Road Service Program that includes overnight exchange Epson Duet Ultra Portable Projector Screen • 80" projection screen • Offers standard (4:3) and widescreen (16:9) formats • Includes floor stand, and bracket for wall-mounting $249 CDWG 1100660 1Express Replacement Assistance with 24-hour replacement. Offer subject to CDW•G’s standard terms and conditions of sale, available at CDWG.com. ©2007 CDW Government, Inc. CCon_OctFall_Temp.inddon_OctFall_Temp.indd 1 99/26/07/26/07 111:45:271:45:27 AAMM 4510_cdwg_Converge_sel_sp_10-1.i1 1 9/10/07 1:13:49 PM 100 Blue Ravine Road Folsom, CA. -

Virtual Pacifism 1

Virtual Pacifism 1 SCREEN PEACE: HOW VIRTUAL PACIFISM AND VIRTUAL NONVIOLENCE CAN IMPACT PEACE EDUCATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS BY JULIA E. LARGENT DR. ASHLEY DONNELLY – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2013 Virtual Pacifism 2 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgement 3 Abstract 4 Foreword 5 Chapter One: Introduction and Justification 8 Chapter Two: Literature Review 24 Chapter Three: Approach and Gathering of Research 37 Chapter Four: Discussion 45 Chapter Five: Limitations and a Call for Further Research 57 References 61 Appendix A: Video Games and Violence Throughout History 68 Appendix B: Daniel Mullin’s YouTube Videos 74 Appendix C: Juvenile Delinquency between 1965 and 1996 75 Virtual Pacifism 3 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Ashley Donnelly, Professor Nancy Carlson, and Dr. Paul Gestwicki, for countless hours of revision and guidance. I also would like to thank my friends and family who probably grew tired of hearing about video games and pacifism. Lastly, I would like to thank those nonviolent players who inspired this thesis. Without these individuals playing and posting information online, this thesis would not have been possible. Virtual Pacifism 4 Abstract Thesis: Screen Peace: How Virtual Pacifism and Virtual Nonviolence Can Impact Peace Education Student: Julia E. Largent Degree: Master of Arts College: Communication, Information, and Media Date: July 2013 Pages: 76 The following thesis discusses how virtual pacifism can be utilized as a form of activism and discussed within peace education with individuals of all ages in a society saturated with violent media. -

Future Bright for Home Media, Analysts Say Page 1 of 3

In searching the publicly accessible web, we found a webpage of interest and provide a snapshot of it below. Please be advised that this page, and any images or links in it, may have changed since we created this snapshot. For your convenience, we provide a hyperlink to the current webpage as part of our service. Future Bright For Home Media, Analysts Say Page 1 of 3 Product Bulletin Special Reports Show Reports PC Magazine My Account | Sign In Not a member? Join now Home > News and Analysis > Future Bright For Home Media, Analysts Say Future Bright For Home Media, Analysts Say 07.07.06 Total posts: 1 By PC Magazine Staff Two separate analyst reports released Thursday paint a rosy future for home media servers and the networks that they will use to pipe content around the home. ABI Research predicted that by 2011, the home media server market will top $44 billion in value, up from $3.7 billion in 2006. In a separate report, Parks Associates forecast that 20 million people would own a "connected entertainment network," of interconnected consumer-electronics devices, or a PC-to-CE network, by 2010. ADVERTISEMENT The PE-CE convergence began in about 2000 when companies like TiVo and ReplayTV began offering personal video recorders that recorded video to a hard drive, like a PC. After failing to capitalize on either its WebTV box or UltimateTV interactive service, Microsoft then introduced its Windows XP Media Center Edition in 2002, which allowed PC owners to connect their breaking news cable feed to the PC and perform the same PVR functions. -

Video Game Violence: a Review of the Empirical Literature

Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 407±428, 1998 Copyright 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 1359-1789/98 $19.00 ϩ .00 PII S1359-1789(97)00001-3 VIDEO GAME VIOLENCE: A REVIEW OF THE EMPIRICAL LITERATURE Karen E. Dill and Jody C. Dill Lenoir-Rhyne College ABSTRACT. The popularity of video games, especially violent video games, has reached phenomenal proportions. The theoretical line of reasoning that hypothesizes a causal relation- ship between violent video-game play and aggression draws on the very large literature on media violence effects. Additionally, there are theoretical reasons to believe that video game effects should be stronger than movie or television violence effects. This paper outlines what is known about the relationship between violent video-game playing and aggression. The available literature on virtual reality effects on aggression is discussed as well. The preponder- ance of the evidence from the existing literature suggests that exposure to video-game violence increases aggressive behavior and other aggression-related phenomena. However, the paucity of empirical data, coupled with a variety of methodological problems and inconsistencies in these data, clearly demonstrate the need for additional research. 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd KEY WORDS. Violence, video games, aggression, virtual reality VIDEO GAME VIOLENCE: A REVIEW OF THE EMPIRICAL LITERATURE All the time people say to me, ªVlad, how do you do it? How come you're so good at killing people? What's your secret?º I tell them, ªThere is no secret. It's like anything else. Some guys plaster walls, some guys make shoes, I kill people.