Indexical Bleaching and the Diffusion of a Media Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

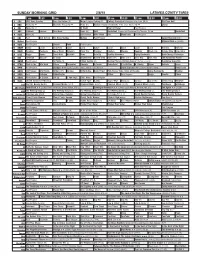

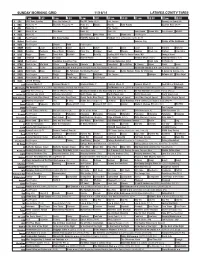

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

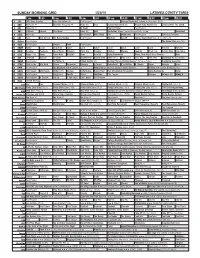

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

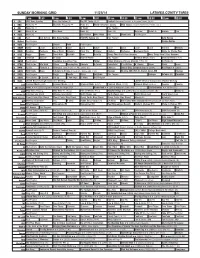

Sunday Morning Grid 11/23/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/23/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Houston Texans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) World/Adventure Sports MLS Soccer: Eastern Conference Finals, Leg 1 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Auto Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Pirates-Worlds 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Monkey 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Barbecue Heirloom Meals Home for Christy Rost 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (9:50) (N) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dhabi. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Sunday Morning Grid

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/16/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Road to the Final Four College Basketball Atlantic 10 Tournament, Final: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Ocean Mys. Explore Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Food City 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Summer Rental ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Tu Vida Tu Vida Familia Familia Mama Toot ¿Ya Llega ¿Ya Llega Iggy Iggy Transform. Transform. 24 KVCR Suze Orman’s Easy Yoga: The Secret Explorer Painting the Wyland Way 2: Great American Songbook (TVG) Å 28 KCET Peep Curios -ity Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Train Your Dog Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Superman: The Movie ››› (1978, Adventure) (PG) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto La Hora Pico (N) República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División 40 KTBN Christ Win Walk Prince Redemption Active Word In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

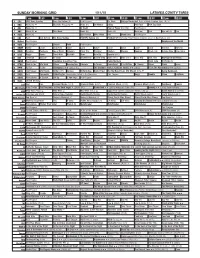

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Sunday Morning Grid 11/16/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/16/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Courage in Sports (N) 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Noodle Noodle Auto Racing Spartan Race (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Veterans Day Pirates of the Caribbean 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD Younger Heart 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Premios Bandamax 2014 Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Superman Returns ››› (2006) Brandon Routh, Kate Bosworth. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Celebrities Hit the Stage for Wbls/Wlib/Hot 97'S Circle of Sisters Explosive Weekend of Dynamic Star Power at the Jacob K

For Immediate Release: COUNTDOWN: CELEBRITIES HIT THE STAGE FOR WBLS/WLIB/HOT 97'S CIRCLE OF SISTERS EXPLOSIVE WEEKEND OF DYNAMIC STAR POWER AT THE JACOB K. JAVITS CENTER! Celebrities Fantasia, Tyrese, Jennifer Hudson, LaLa Anthony, Tamar Braxton & Vince Herbert, Niecy Nash & Jay Tucker, Rebecca & Terry Crews, Tamela & David Mann, Bevy Smith & Miss Lawrence, Dr. Rachael Ross, Lance Gross, Mary Mary’s Tina Campbell; Chefs Pat Neely, Nikki Shaw, Lisa Fernandez, Melba Wilson, and Madison Cowan share their talents & expertise Casts of Blood, Sweat and Heels, Orange is the New Black & Hollywood Divas Join #COS2014 #CircleofSisters New York, NY (October 1, 2014) – The 10th Anniversary of Circle of Sisters, presented by AARP in association with AT&T and Della Russo, is a weekend not to be missed as it’s the largest EXPO in New York City uniting, motivating and celebrating women of color. The event takes place Saturday, October 4 and Sunday, October 5, 2014 at the Jacob Javits Center, 34th Street and 11th Avenue. “We have singers, entertainers, reality stars, celebrity chefs; fitness, finance, health experts and more,” says Deon Levingston, Vice President/General Manager of Emmis New York. “But, it doesn’t just stop there: we will feature a fashion show, R&B and Gospel Concerts, Cooking & Kids Pavilions and a Man Cave – something for everyone who wants to be entertained!” The main stage will host unique panels with R&B Veterans including Grammy Award- winning Recording Artist Faith Evans, Grammy-nominated R&B Singer-Songwriter, Actor and Author Tyrese Gibson and Grammy winning-artist Johnny Gill; a host of Reality TV stars and a few dashing celebrities couples such as Niecy Nash & Jay Tucker, Rebecca & Terry Crews, and Tamela & David Mann. -

TV Talk Layout

ALL AMERICAN FREE PAESANO’S A&W GOLD DANCE DELICATESSEN & STEAK FREE BUYERS LESSONS CATERING HOUSE Page 7 Page 14 Page 17 Page 18 th Anniversary37 JAN.1976 JAN. 2013 A WEEKLY MAGAZINE June 22-June 28, 2013 Tel. 201-437-5677 Visit Us On The Web at www.TVTALKMAG.com 3 FREE Call TANS* No Purchase 201 Necessary *New Customers Only & 535-5900 Level One Beds Only. Offer Expires 6/30/13 South Cove Commons Story Pg. 12 Shopping Center Ad Pg. 13 116 Lafante Way (next to Staples) Bayonne, NJ Join Our Unlimited Prices Start At $ 95 CAR WASH CLUB 14 per month 1505 Kennedy Blvd. (At City Line) Jersey City, NJ CAR WASH See Page 7 For Ad With Valuable Coupons THIS WEEKS PICKS CASH FOR GOLD! Sunday ThurSday CASH FOR GOLD! RECORD HIGH PRICES Must Bring This Jackson Gildart wel- Lauren Holly stars as PAID FOR YOUR GOLD! Coupon For An comes contestants to Dr. Betty Rogers, a put their investigative medical examiner YOU WILL BE AMAZED! Extra 10% More skills to the test to with a quirky sense We Will Buy All Your Gold & Silver Coins For Your Gold solve a murder of humor, in mystery on “Motive” We also buy Platinum & Diamonds, Collectibles HIGHEST PRICES “Whodunnit?” Thursdays on ABC. Baseball Cards, Pocket Watches, Broken Jewelry, PAID FOR YOUR premiering Sunday Foreign Coins and yes, even Costume Jewelry *SILVER DOLLARS on ABC. For your convenience, mail us you gold, *In Good Condition postage free or you can make an $2000 appointment for us to come to you. -

TV Talk Layout

A&W STEAK NAPLESRestaurant FREE HOUSE & Pizzeria Page 7 Page 11 Page 15 Page 22 th Anniversary37 JAN.1976 JAN. 2013 A WEEKLY MAGAZINE May 18-May 24, 2013 Tel. 201-437-5677 Visit Us On The Web at www.TVTALKMAG.com Bayonne Swimming Pool Center Cor. of 9th St. & Ave. E, Bayonne, NJ (201) 823-3702 Story Pg. 10 Ad Pg. 13 • Steel Pools • Sturdy Top Rails • Durable Uprights • Safety Ladders • Hayward Parts • Deck Ladders • Replacement Liners • Lomart Parts • Chlorine & More Join Our Unlimited Prices Start At $ 95 CAR WASH CLUB 14 per month 1505 Kennedy Blvd. (At City Line) Jersey City, NJ CAR WASH See Page 6 For Ad With Valuable Coupons TThhee CASHCASH FORFOR GOLD!GOLD! RECORD HIGH PRICES Must Bring This PAID FOR YOUR GOLD! Coupon For An GARDEN CENTER at 440 FARMS YOU WILL BE AMAZED! Extra More STOCK-UP ON SPECIALLY PRICED SOIL & PLANTS 10% We Will Buy All Your Gold & Silver Coins For Your Gold Compost MULCH TOP We also buy Platinum & Diamonds, Collectibles HIGHEST PRICES Red, Black & Brown COW Baseball Cards, Pocket Watches, Broken Jewelry, PAID FOR YOUR 2 cub. ft. Bags SOIL MANURE Foreign Coins and yes, even Costume Jewelry *SILVER DOLLARS $ 40 lb. Bags for 40 lb. Bags For your convenience, mail us you gold, *In Good Condition 3 10 $ 00 $ $ $ postage free or you can make an 20 or 3.99 each 5 for 10 3 for 10 appointment for us to come to you. (with this ad) Premium Hampton Estates Locally Grown For details call 201-823-1720 WE HONOR LEGITIMATE OFFERS NOW OPEN SUNDAYS 11 AM-4 PM License# 08-42 Professional Emerald Green FREE INSTALLATION ON GARDEN SOIL Se Habla Español POTTING MIX ARBORVITAES Mówlmy Popolsku One cub. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/8/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/8/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s Final. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. (6) (N) Å Formula One Racing Canadian Grand Prix. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild X Games Austin. (N) Å 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Save the Last Dance 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Healing ADD With-Amen Bob Ross: The Happy Painter (TVG) 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Skills (TVG) Å 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Ed Slott’s Retirement 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Bull Durham ››› (1988) Kevin Costner. (R) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) Pocoyo Jungle B’k Tras la Verdad Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Marmaduke › (2010) Owen Wilson, Lee Pace.