The Black Woman That Media Built: Content Creation, Interpretation, and the Making of the Black Female Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network BET.com is a Multi-Platform Mega Star, Setting Trends Worldwide with over 6 Billion Multi-Screen Fan Impressions BET Networks Announces More Hours of Original Programming Than Ever Before Centric, the First Network Designed for Black Women, is One of the Fastest Growing Ad - Supported Cable Networks among Women NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- BET Networks announced its upcoming programming schedule for BET and Centric at its annual Upfront presentation. BET Networks' 2015 slate features more original programming hours than ever before in the history of the network, anchored by high quality scripted and reality shows, star studded tentpoles and original movies that reflect and celebrate the lives of African American adults. BET Networks is not just the #1 network for African Americans, it's an experience across every screen, delivering more African Americans each week than any other cable network. African American viewers continue to seek BET first and it consistently ranks as a top 20 network among total audiences. "Black consumers experience BET Networks differently than any other network because of our 35 years of history, tremendous experience and insights. We continue to give our viewers what they want - high quality content that respects, reflects and elevates them." said Debra Lee, Chairman and CEO, BET Networks. "With more hours of original programming than ever before, our new shows coupled with our returning hits like "Being Mary Jane" and "Nellyville" make our original slate stronger than ever." "Our brand has always been a trailblazer with our content trending, influencing and leading the culture. -

FILMS MANK Makeup Artist Netflix Director: David Fincher SUN DOGS

KRIS EVANS Member Academy of Makeup Artist Motion Picture Arts and Sciences IATSE 706, 798 and 891 BAFTA Los Angeles [email protected] (323) 251-4013 FILMS MANK Makeup Artist Netflix Director: David Fincher SUN DOGS Makeup Department Head Fabrica De Cine Director: Jennifer Morrison Cast: Ed O’Neill, Allison Janney, Melissa Benoist, Michael Angarano FREE STATE OF JONES Key Makeup STX Entertainment Director: Gary Ross Cast: Mahershala Ali, Matthew McConaughey, GuGu Mbatha-Raw THE PERFECT GUY Key Makeup Screen Gems Director: David M Rosenthal Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Michael Ealy, Morris Chestnut NIGHTCRAWLER Key Makeup, Additional Photography Bold Films Director: Dan Gilroy HUNGER GAMES MOCKINGJAY PART 1 & 2 Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Francis Lawrence THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Francis Lawrence THE FACE OF LOVE Assistant Department Head Mockingbird Pictures Director: Arie Posen THE RELUCTANT FUNDAMENTALIST Makeup Department Head Cine Mosaic Director: Mira Nair Cast: Riz Ahmed, Kate Hudson, Kiefer Sutherland ABRAHAM LINCOLN VAMPIRE HUNTER 2012 Special Effects Makeup Artists th 20 Century Fox Director: Timur Bekmambetov THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2012 Makeup Artist Columbia Pictures Director: Marc Webb THE HUNGER GAMES Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Gary Ross THE RUM DIARY Key Makeup Warner Independent Pictures Director: Bruce Robinson Cast: Amber Heard, Giovanni Ribisi, Amaury Nolasco, Richard Jenkins 1 KRIS EVANS Member Academy of Makeup Artist -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

“Being Mary Jane” on USO Tour to Naval Base San Diego Richard Roundtree, B.J

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: February 19, 2015 Oname Thompson (703) 908-6481 office [email protected] Stars Celebrate the Season Two Return of BET’s “Being Mary Jane” On USO Tour to Naval Base San Diego Richard Roundtree, B.J. Britt and Aaron Spears visit with sailors and their families, and go on tour of installation ARLINGTON, VA. (February 19, 2015) – BET Networks has joined forces with the USO once again, this time treating Naval Base San Diego with a USO visit on Feb. 17 featuring stars from their number one rated television show “Being Mary Jane,” to include actors Richard Roundtree, B.J. Britt and Aaron Spears. On a mission to help the USO make more great #USOMoments in 2015, the group spent the entire day with sailors and their families, and even took time out to learn about the base’s important mission and extensive fleet of Navy ships. **USO photo link below** DETAILS: Roundtree, Britt and Spears kicked off their USO visit with a meet & greet with sailors and their families at the Waterfront Recreation Center, followed by a lunch on base. The group then went on a tour of Naval Base San Diego, where they learned about the base’s mission and operations, and viewed various ship platforms. Roundtree, Britt and Spears join a growing list of famous faces who have participated in USO tours and worked closely with BET over the years. Among other BET stars (both past and present) who have volunteered with the USO to visit and/or entertain troops are Nick Cannon (“Real Husbands of Hollywood”), Keyshia Cole (“Keyshia Cole: All In”) and Rocsi Diaz (“106 & Park”). -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Yasmin Peace Series Book 3 Contents

Table of Contents Finding Your Faith Believing in Hope Experiencing the Joy Learning to Love Enjoying True Peace Finding Your Faith Yasmin Peace Series Book 1 Stephanie Perry Moore MOODY PUBLISHERS CHICAGO Contents Chapter 1 Prayer Does Work 9 Chapter 2 Expresser of Emotion 21 Chapter 3 Matter of Fact 35 Chapter 4 Whatever I Got 47 Chapter 5 Stranger Things Happened 59 Chapter 6 Worrier by Default 73 Chapter 7 Observer of Drama 87 Chapter 8 Madder Each Moment 97 Chapter 9 Wiser through Visiting 109 Chapter 10 Never Work Out 121 Chapter 11 Better than Before 133 Chapter 12 Believer Deep Within 143 Acknowledgments 155 Discussion Questions 157 Believing in Hope Excerpt 161 Chapter 1 Prayer Does Work Get out! Me and my kids need some space. I’m sick of everybody trying to console us. Leave us alone.”My mom was screaming at the thirty or so friends and family members that came to offer their condolences after the funeral of my oldest brother, Jeffery Jr. Everybody called him Jeff. Everyone stopped and looked at her. However, no one moved or walked toward the door.The tension was thicker than a plump, round turkey on Thanksgiving. “Mom, here. Have some tea,” I said, trying to soothe her. She knocked the cup from my hand sending it flying across the room. I’d never seen my mother this way. Mom went over to the front door, opened it, and said,“Yasmin, York, Yancy, and I are going to have to find a way to deal with this. My husband is down in Orlando in jail, while we’re up here in Jack- sonville grieving over the loss of my oldest baby. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE BLACK SELF-DETERMINATION EXPERIENCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHAUNCEY DEMOND GOFF Norman, Oklahoma 2010 THE BLACK SELF-DETERMINATION EXPERIENCE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY BY ___________________________ Dr. James E. Martin, Chair ___________________________ Dr. James E. Gardner ___________________________ Dr. George Henderson ___________________________ Dr. Dorscine Spigner-Littles ___________________________ Dr. Raymond B. Miller © Copyright by CHAUNCEY DEMOND GOFF 2010 All Rights Reserved. DEDICATION In memory of you, I lovingly dedicate this to me. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledging all those who assisted in this process would be virtually impossible, for there were individuals who offered kind words as I sat in a library, pumped gas, visited the writing center, etc. Thus, I ask that anyone who feels omitted understands that you have each been a part of the process and are now classics. I give all honor to God for without him none of this would be possible. I give honor to Robert and Lillie Goff, for without them, I would not be possible. I give honor to Aaron and Cameron Goff for all the inspiration they provided, as I sought to be your father. I give honor to Bigstuff for suggesting that I attend graduate school and informing me about its potential benefits. I give honor to my brother Cameron for helping me find me. I give honor to Wanda Taylor for giving me a place to sleep as I matured through college (Gaines says thanks for the cookies). -

Controversial “Conversations” Analyzing a Museum Director’S Strategic Alternatives When a Famous Donor Becomes Tainted

Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership 2019, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 85–106 https://doi.org/10.18666/JNEL-2019-V9-I1-8390 Teaching Case Study Controversial “Conversations” Analyzing a Museum Director’s Strategic Alternatives When a Famous Donor Becomes Tainted Jennifer Rinella Katie Fischer Clune Tracy Blasdel Rockhurst University Abstract This teaching case places students in the role of Dr. Johnnetta Cole, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, as she determines how to respond to a situation in which Bill Cosby—well-known entertainer, spouse of a museum advisory board member, donor, and lender of a significant number of important pieces of art on display at the Museum—has been charged with sexual misconduct. Representing the Museum, the director must weigh the cost of appearing to support her friends the Cosbys against the value of displaying one of the world’s largest private collections of African American art. This case extends stakeholder theory by utilizing Dunn’s (2010) three-factor model for applying stakeholder theory to a tainted donor situation. Keywords: arts administration; philanthropy; stakeholder theory; crisis communication; nonprofit leadership; tainted donor; ethical decision making Jennifer Rinella is an assistant professor of management and director of the nonprofit leadership program, Helzberg School of Management, Rockhurst University. Katie Fischer Clune is an associate professor of communication, College of Business, Influence, and Information Analysis, Rockhurst University. She is also director of the university’s Honors Program. Tracy Blasdel is an assistant professor of management and marketing, Helzberg School of Management, Rockhurst University. Please send author correspondence to [email protected] • 85 • 86 • Rinella, Clune, Blasdel This teaching case offers an opportunity for students and practitioners to apply an important theoretical model for decision making to a real-life situation involving a tainted donor. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS System Requirements . 3 Installation . 3. Introduction . 5 Signing In . 6 HOYLE® PLAYER SERVICES Making a Face . 8 Starting a Game . 11 Placing a Bet . .11 Bankrolls, Credit Cards, Loans . 12 HOYLE® ROYAL SUITE . 13. HOYLE® PLAYER REWARDS . 14. Trophy Case . 15 Customizing HOYLE® CASINO GAMES Environment . 15. Themes . 16. Playing Cards . 17. Playing Games in Full Screen . 17 Setting Game Rules and Options . 17 Changing Player Setting . 18 Talking Face Creator . 19 HOYLE® Computer Players . 19. Tournament Play . 22. Short cut Keys . 23 Viewing Bet Results and Statistics . 23 Game Help . 24 Quitting the Games . 25 Blackjack . 25. Blackjack Variations . 36. Video Blackjack . 42 1 HOYLE® Card Games 2009 Bridge . 44. SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS Canasta . 50. Windows® XP (Home & Pro) SP3/Vista SP1¹, Catch The Ten . 57 Pentium® IV 2 .4 GHz processor or faster, Crazy Eights . 58. 512 MB (1 GB RAM for Vista), Cribbage . 60. 1024x768 16 bit color display, Euchre . 63 64MB VRAM (Intel GMA chipsets supported), 3 GB Hard Disk Space, Gin Rummy . 66. DVD-ROM drive, Hearts . 69. 33 .6 Kbps modem or faster and internet service provider Knockout Whist . 70 account required for internet access . Broadband internet service Memory Match . 71. recommended .² Minnesota Whist . 73. Macintosh® Old Maid . 74. OS X 10 .4 .10-10 .5 .4 Pinochle . 75. Intel Core Solo processor or better, Pitch . 81 1 .5 GHz or higher processor, Poker . 84. 512 MB RAM, 64MB VRAM (Intel GMA chipsets supported), Video Poker . 86 3 GB hard drive space, President . 96 DVD-ROM drive, Rummy 500 . 97. 33 .6 Kbps modem or faster and internet service provider Skat . -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

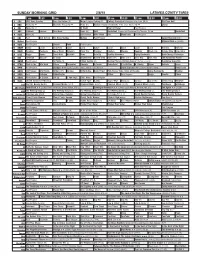

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

![February 2007 [.Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5132/february-2007-pdf-605132.webp)

February 2007 [.Pdf]

PIPER2/07 Issue 3 A SK A NDREW Hello Mrs. Huxtable 4 N EWS B RIEFS 7 I NTERN A TION A L D ISP A TCHES 8 L ECTURE S POTLIGHT For Addicts, It’s All About the Craving n Jonathan Potts Of all the researchers devoted to study- EYO R ing drug addiction, hardly anyone has D An ever asked the most important question, N says George Loewenstein: Why? Y K E “There is so much research on B addiction and drug abuse, and amazingly P H O T O little of it is focused on the central ques- M OST P EO P LE REMEMBER HER AS C LAIR H UXTABLE ON THE TELEVISION SMASH “ T HE C OSBY S HO W , ” BUT ACTRESS tion of why people take drugs in the first P HYLICIA R ASHAD HAD MORE ON HER MIND THAN SITCOMS W HEN SHE S P OKE IN C ARNEGIE M ELLON ’ S P HILI P C HOSKY place,” said Loewenstein, the Herbert T HEATER LAST W EEK . I N “ A D IALOGUE W ITH P HYLICIA R ASHAD , ” ALUMNUS D AN G REEN ( A’ 9 4 ) S P OKE W ITH THE T ONY A. Simon Professor of Economics and A W ARD - W INNING ACTRESS ON EVERYTHING FROM HER P ROCESS FOR DEVELO P ING A CHARACTER TO HER TAKE ON P ITTSBURGH , Psychology and a world-renowned re- W HICH SHE DEEMED “ FASCINATING . ” A ND W HILE THE AUDIENCE TREATED R ASHAD TO T W O STANDING OVATIONS , SHE MADE searcher on the psychology of intertem- NO SECRET OF J UST HO W MUCH HER TRI P TO C ARNEGIE M ELLON AND MENTORING SESSIONS W ITH S CHOOL OF D RAMA poral choice — or decisions that require STUDENTS MEANT TO HER . -

Pandora Predicted to 'Dominate' Web Radio for Next Few Years

Pandora Predicted To 'Dominate' Web Radio For Next Few Years With concerns about profitability and iTunes Radio about to launch, there's a lot of uncertainty around Pandora's future. But one recent report from IBISWorld claims that Pandora will continue to dominate web radio. Given that its stock recently hit new highs and mobile advertising is showing strong growth, Pandora actually has a lot going for it at the moment. The recently teased IBISWorld report (via RAIN) notes that over the last five years: "The number of mobile internet connections grew at an annualized rate of 53.0% during the five- year period. 'As such, internet radio's audience increased an annualized 16.5% during the same period, far outpacing traditional radios,' according to IBISWorld industry analyst David Yang. Consequently, internet radio broadcasters have taken a larger slice of advertising revenue from the $17.3-billion Radio Broadcasting industry." Though citing positive usage and ad growth stats for web radio, the report also pointed to challenges with profitability due, in part, to the much higher royalty rates web radio broadcasters pay than do terrestrial radio broadcasters. The IBISWorld analysts expect leaders such as Pandora, iHeart Radio and, most likely, the soon- to-launch iTunes Radio to maintain their lead with Pandora continuing to "dominate the marketplace as new entrants will have a difficult time attracting listeners away from well- established services." They also expect future competition to be limited, in part, "as new entrants will hesitate to enter the industry due to the inability of major players to operate profitably." So Pandora's leading in a race with many challenges.