INTRODUCTION (Revisiting the Art of Ultralight)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Mountain Club 2009 Donors to CMC Annual Campaign [Oct

The Colorado Mountain Club ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Annual Report 2009 1 From the Chief Executive Officer he past year was an Dominguez Escalante National Conservation Area just south incredibly challenging time of Grand Junction. On the Front Range, we celebrated the for our entire country, designation of Rocky Mountain National Park’s backcountry Teconomically speaking. Businesses as wilderness. This designation is one of the final chapters in around the country failed, and the long journey of protecting the beloved park the CMC many people saw their personal played a major role in creating in 1915. finances change significantly. Every Our Youth Education Program introduced nearly once in awhile an event happens 5,000 youth and their chaperones to an education only the that makes all of us change our great outdoors can bring, and we furthered our work with focus and get back to basics. In the severely disabled children. I can’t tell you what an honor it nonprofit world, buckling down was for me to watch a young man who has been wheelchair while still achieving our goals is bound his entire life get to the top of our climbing wall. That not new to us; we always make experience alone gave me strength to get through last year’s magic happen with very little. I’m tough times. proud to report that the Colorado The upcoming year will be another time of growth Mountain Club saw a number of and change for the CMC. We are inching our way closer to achievements this past year despite our 100th anniversary and have begun a rebranding project the economic challenges. -

Lightweight Backpacking – a Journey to Higher Adventure Chris Knaus LEAD; January 2016

Lightweight Backpacking – A Journey to Higher Adventure Chris Knaus LEAD; January 2016 Ediza Lake and Minarets. Ansel Adams Wilderness. Sept 2009 Objectives, Disclaimer and Reminder . Objective: Awareness • Share experiences to help you and your Scouts learn about lightening- up and the possibilities offered, and • Describe a process to help you lighten-up. • Highlight some gear choices and ways to think about gear. Disclaimer: • Views are mine only. BSA officialdom and the High Emigrant Lake. July 2006 Adventure Team do not necessarily Note frame pack, before endorse all of what I describe here. my lightweight journey . Reminder: Be Prepared. Scout began. safety is your prime responsibility. Lightweight Backpacking. A Journey to Higher Adventure. 2 Introduction - Who am I? . Backpacking since age 12 . Cub Scout, Boy Scout & Explorer . Troop 236 (Danville) . Current Scouting Roles • HAT Core, BBA & OKPIKStaff • Former Meridian District Committee Chair & MDSC Board Member . Currently enjoy backpacking with “ex-Scout Dads” including J Muir Trail (2013) & High Sierra Trail (2015). Timberline Lake & Mt. Whitney. Sept 2015. Lightweight Backpacking. A Journey to Higher Adventure. 3 Old school - does this look like fun? Emigrant Wilderness. Aug 2004 Lightweight Backpacking. A Journey to Higher Adventure. 4 Lightweight backpacking is not universally accepted. Arguments include… For lightening-up Against lightening-up Less wear and tear on body Thinner margin for error Heightened enjoyment May push your experience Ability to go farther each day Cost Capacity for other goals Miss creature comforts Goal: To strike a safe balance between extremes. Lightweight Backpacking. A Journey to Higher Adventure. 5 Bottom Line: It is almost impossible to enjoy a trail like this with a heavy pack. -

Wilderness Equipment List (Side One)

Wilderness Equipment List (Side One) ***Please note that HMI has an ample supply of rental items and the cost of the Educators Expedition tuition includes all-inclusive wilderness gear rentals. The tuition does not include gear purchases from HMI. One advantage to renting gear is that it will give you the opportunity to try the gear before you buy it. Prices listed below are for rental or purchase depending on whether HMI rents or sells the items, and are listed for your reference. Highlighted items are typically rented or purchased by more than half of the students that come to HMI. * signifies gear that can be rented from HMI. ** signifies gear that can be purchased from HMI. You will need all of the items on this list for the backcountry expeditions. It is very important that you can wear all of your layers at the same time. If you cannot wear them at the same time, your clothing will be too tight and constrict blood flow, and therefore not keep you warm. Your sizes may need to be progressively larger in size to accommodate this. Lightweight and compressible clothing and equipment will make your pack lighter and easier to pack. Please remember to put your name on everything. BACKPACK AND OTHER STORAGE BAGS *Backpack (Please read the Equipment Information page very carefully.) [36.00] **3 Heavy Duty Trash Compactor or Contractor plastic bags [1.00] *Day Pack (Standard school backpacks are typically too bulky to use here.) [12.00] *1-2 Small Stuff Sacks (These help you organize items in your pack. -

Ice Age Trail Alliance Staffer, and Warning at the End of I Did

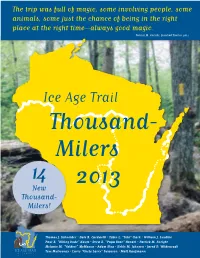

The trip was full of magic, some involving people, some animals, some just the chance of being in the right place at the right time—always good magic. Patrick M. Enright, finished Trail in 2013 Ice Age Trail Thousand- Milers 14 2013 New Thousand- Milers! Thomas J. Schneider • Dale R. Cardwelll • Tobin L. “Tobi” Clark • William J. Luedtke Paul R. “Hiking Dude” Kautz • Drew R. “Papa Bear” Hendel • Patrick M. Enright Melanie M. “Valderi” McManus • Adam Hinz • Kehly M. Johnson • Jared D. Wildenradt Tess Mulrooney • Larry “Uncle Larry” Swanson • Matt Kaufmann 2013 Thousand-Miler Program The Ice Age Alliance (IATA) established an official Thousand-Miler program in 2002; however, recognition is given below to all who have hiked the entire Trail How to Earn a including the road connections. Names in bold are thru-hikers. Names in the tan Thousand-Miler box are the newest Thousand-Milers; their stories are told in this book. Certificate The IATA recognizes Thousand-Milers through the Years anyone who reports (bold = thru-hikers) having hiked the entire Trail and completes a Jim Staudacher (1979) Jane M. Stoltz (1993–2009) recognition application Rev. Harry J. Gensler, S.J. (1983) Chet “Gray Ghost” Anderson (2009) as a “Thousand-Miler.” Ken & Sally Waraczynski (1983–1989) Russ & Clara Marr (2009) The IATA policy operates Tim M. “Ya Comi” Malzhan (1991) James R. Brenner (2003–2010) on the honor system, Clarman “Salty” Salsieder (1995) Dave A. Caliebe (2010) assuming anyone who Tom Menzel (1996) Donene Rowe “Ice Age Three Erractics” applies for recognition Mark & Kathy Vincent (1997) (2003–2011) has hiked all 1000+ miles Dave Kuckuk & Yukon (1998) Linda J. -

Turn up the Heat Combat the Cold This Winter with Insulating Layers

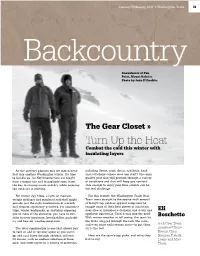

January+February 2011 » Washington Trails 31 Backcountry Snowshoers at Pan Point, Mount Rainier. Photo by John D’Onofrio. The Gear Closet » Turn Up the Heat Combat the cold this winter with insulating layers As the mercury plunges and we march head- including fleece, wool, down, synthetic, hard first into another Washington winter, it’s time and soft-shells—where does one start? Choosing to bundle up. As Northwesterners are taught quality gear that will perform through a variety from a young age and transplants soon learn, of conditions and that will keep you comfort- the key to staying warm and dry while enjoying able enough to enjoy your time outside can be the outdoors is layering. the real challenge. For winter day hikes, a light- or medium- For this feature, the Washington Trails Gear weight midlayer and insulated soft-shell might Team went straight to the source with several provide just the right combination of warmth of today’s top outdoor apparel companies to and element repellency you need. For snowshoe sample some of their best pieces of insulation trips, winter backpacks, or anything exposing gear—fleece, insulated soft-shells, and down and Eli you to more of the elements, you have to con- synthetic outerwear. Then it was into the field! sider heavier insulation, breathability, packabil- With winter weather in full swing, the team hit Boschetto ity and heavier weather-resistance. the trails, slogged through the rain, the cold— and even some early-season snow—to put them with Gear Team The ideal combination is one that allows you all to the test. -

Colorado Mountain Club 2010 Donors to CMC Annual Campaign [Oct

The Colorado Mountain Club ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Annual Report 2010 1 From the Chief Executive Officer s I look back on my past working internally and externally to strengthen our brand, to three years as the Colorado inspire people to join the CMC as members and to support the Mountain Club’s CEO, one club as donors. Athing that pleases me tremendously After two years of discussions, the CMC signed is our consistent commitment to the largest-ever partnership agreement between the major educating the outdoor, human- mountaineering clubs of the U.S. As a member of the CMC, powered recreationists of our you will now receive the member rates of the Adirondack state, while working to protect our Mountain Club, the American Alpine Club, the Appalachian beautiful Colorado landscapes. Mountain Club, the Mazamas, and the Mountaineers on a I am proud of the adaptations host of their perks and benefits, including huts. I encourage all the club has gone through this past of you to plan a trip to Seattle or to the Appalachians and stay year in order to meet the changing in some of the great lodges and cabins offered by our partners. needs of our community. One Lastly, I am very pleased to announce that the CMC of the strengths of the CMC’s finished the 2010 fiscal year with a healthy cash surplus. Over mission and values is that they can the past two years of the recession, we have worked even more be carried out in a variety of ways, efficiently to fulfill our mission, grow the organization, and to which has allowed the organization build a savings account for future projects. -

![Therefore I Golite. a MESSAGE from the FOUNDERS [GRI 1.1, 1.2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1097/therefore-i-golite-a-message-from-the-founders-gri-1-1-1-2-10501097.webp)

Therefore I Golite. a MESSAGE from the FOUNDERS [GRI 1.1, 1.2]

2009 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT Transparency weighs nothing. Therefore I GoLite. A MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDERS [GRI 1.1, 1.2] GoLite started as a simple idea: that experiencing nature would be better with less. Less weight, less fuss, less waste…and more fun. It’s a philosophy that drives us to make simple, beautiful, high performance gear that’s light on the planet. It is also a philosophy that makes us committed to building a sustainable business. Sustainability has been part of our ethos since our founding in 1998. It is imbedded in every aspect of how we operate through an integrated set of guidelines, policies, and company and individual goals, all bound together by our mission, vision, and shared values. Building a sustainable business is an expression of our brand essence and our passion. It is also good for our planet, good for our customers, and good for our business. Our definition of sustainability includes respect for everyone involved in our supply chain from fabric mill workers, to our employees, to our valued customers. It includes strong financial performance, and it includes avoiding or minimizing the environmental impacts of producing our products. Long-term, we are striving to achieve a value chain that goes beyond leave no trace and eventually nourishes the environment. We want to be a real part of the solution to the challenges facing our planet. We are making aggressive changes in how we do business, because we want to reach a truly sustainable – and replicable – business model as fast as possible while continuing to make premium, high-performance products that serve the needs of outdoor athletes. -

Buyer Could Snare Spyder for up to $150 Million by BETH POTTER for Comment

1A 1A SCHOOL GUIDE OUTDOOR INDUSTRY Primrose preps tots Slacklining company for academic success suggests park for city $1 11A 15A Volume 31 Issue 18 | Aug. 17-30, 2012 Green Summit Dean hopes Conference blends business, environmental awareness WhiteWave IPO yields $300 million Company makes Silk, Horizon Organic lines BY BETH POTTER [email protected] BROOMFIELD — Dean Foods Co. plans to raise up to $300 million by selling 20 percent of The White- Wave Foods Co., distributor of Silk soy products and Horizon Organic milk, in an initial public offering. Broomfield-based WhiteWave Foods will be listed on the New York Stock Exchange as WWAV, accord- ing to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission documents filed Aug. 7. WhiteWave, listed as the White- Wave-Alpro unit of Dallas-based JONATHAN CASTNER Dean Foods (NYSE: DF), listed Sarah Van Pelt, environmental coordinator at Western Disposal Services Inc., speaks during the Boulder County Busi- assets of more than $2 billion in the ness Report’s “Green Summit: Blending Business & The Environment,” which drew 140 attendees to the Millennium Har- most recent quarter ended June 30, vest House Boulder. Western Disposal was one of the Aug. 7 event’s major sponsors. See story, 20A. according to an SEC document. The ➤ See WhiteWave, 17A Buyer could snare Spyder for up to $150 million BY BETH POTTER for comment. [email protected] Ski-clothing company reportedly up for sale Apax acquired a controlling inter- est in Spyder in 2004 for about $100 BOULDER — Ski clothing com- private-equity firm, has retained ment on market speculation about million. -

American Mountaineering Museum Director Shelby Arnold, Drive

Colorado Mountain Club ANNUAL REPORT 2013 F C E O ollowing a experience as well as our member oerings. While I’m not sure we centennial have the answer to why membership organizations, including ours, year for an are declining, I am condent that we are focused on improving our Forganization can be organization and making it a place where people join because we are a little like a new more than just a recreation club. My hope is that our new members performer following feel proud that when they join the CMC, they are personally helping up a major act to protect the mountain landscapes and to educate the people of our that just had the great state, both young and old. performance of a lifetime. e CMC’s e CMC is proud to oer a variety of programming under our Centennial year mission umbrella, and nd it a great strength in the overall nancial was one that will health of the club. Our Youth Education Program had a stellar year, go down in history, impacting more than 6,600 youth. Our Conservation department and many people started work on a new wilderness designation right here on the Front wondered what our 101st year would be like. I’m happy to report that Range. All of this good news would not be possible without the 2013 has been a strong and progressive year for the CMC in many generous support of our members and friends. As you can see on page areas. We started year one of our 5-year strategic plan. -

Going Light Lightweight Backpacking 2020

Going Light Lightweight Backpacking 2020 Steve LeBrun & Michael Montgomery Going lightweight helps us go to amazing places, like the Oregon Eagle Cap Wilderness Overview • Course Goals / Objectives • Sleeping Bags • Shelters • Packs • (Food) / Water • Clothing • Misc. • Weigh your gear! Goal Our goal is to help you create your own personal lightweight system -- one that fits your needs, budget, and style -- by making informed, thoughtful choices. In honor of…. Emma “Grandma” Gatewood "Make a rain cape, and an over the shoulder sling bag, and buy a sturdy pair of Keds tennis shoes. Stop at local groceries and pick up Vienna sausages.” In honor of… Ray Jardine His1992 book “PCT Hiker's Handbook,” later retitled as Beyond Backpacking in 1999, laid the foundations for many techniques that ultralight backpackers use today. Jardine claimed his first Pacific Crest Trail thru-hike was with a base pack weight of 12.5 pounds and by his third PCT thru-hike it was below 9.0 pounds Focus Focus: • 3-season • Subalpine • Temperate climates. The principles discussed will still mostly apply outside this scope. What are other factors that impact choices? Goals / Objectives • Help you develop a lightweight mindset • Inform you of alternatives • Empower you to incrementally lighten your load, by finding the right balance of gear need, preference, performance, versatility, repackaging, durability and price. • Enable you to make informed decisions about what to ask, what to buy, what to bring Non-Goals What this course is NOT about • Telling you what [not] -

Light and Fast Backpacking National Outdoor Leadership School

Equipment List Light and Fast Backpacking National Outdoor Leadership School Welcome to NOLS Light and Fast Backpacking (LFB)! The goal of this course is to safely camp and travel in a mountain environment with the lightest backpack possible. NOLS is a school, and we will be teaching the essentials of lightweight camping along with our standard curriculum. Please be aware this is a very specialized expedition focusing on a unique type of wilderness travel. By necessity, we are going to be very strict with every item that goes into the backpack. This equipment list is the culmination of a lot of testing and research in real-life mountain conditions by the staff here at NOLS. To ensure success, you’ll be required to purchase or bring some very specific lightweight gear. NOLS Rocky Mountain (RM) will carry some of this gear for purchase (see end of document), but the majority of this specialized gear will be your responsibility to purchase before arriving in Lander. If you already own items on the list and you’d like to bring them, please do. Your instructors will review your gear with you and help you decide if it is appropriate for the course. Remember, the ultimate goal is a full backpack (that’s with food, water, fuel, personal and group gear) that weighs less than 25-30 pounds! With the sub 30-pound goal in mind, we created a detailed list, which includes the weight allowances for each piece of gear. These numbers are extremely important, please make sure each item matches (or weighs less than) the weights listed. -

Free Chickens

Archived thesis from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA at ASHEVILLE FREE CHICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL ARTS BY BECCA CHAMBERS ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA DECEMBER 2014 The Final Project FREE CHICKENS by BECCA CHAMBERS is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Arts degree at The University of North Carolina at Asheville. Signature John Wood, Ph.D. Project Advisor Department of Sociology and Anthropology ________________ ________________ Signature Holly Iglesias, Ph.D. MLA 680 Instructor _______________ _________________ Signature MLA Graduate Council Date: i I heard once that chickens in captivity won’t lay eggs. To give the chickens illusions of freedom, big chicken farms let a few of the birds roam around so the rest think they aren’t captives. Thru-hikers are our society’s equivalent to the free chickens. We roam around free convincing people who won’t quit jobs they hate that they aren’t wage-slaves. Enjoy your freedom free chickens. Enjoy every day. Dave “Vegas” McNeil Manassas Gap Shelter Log June 2008 Chambers 1 Part I Chapter 1 – Georgia Time To Go Thursday, April 3, 2008 I am aware of a few certainties: I will be cold; I will walk through rain – a lot of rain; blisters; I will be hungry; happiness, sadness, fear and bewilderment will all be experi- enced; pain and soreness will be felt everyday; and I'll learn even more about myself. I can't wait to get started.