Inquiry Journal of Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ Por Day Per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'iace in Book Return to Remove Chars

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ por day per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'Iace in book return to remove chars. from circuhtion recon © Copyright by JACQUELINE KORONA TEARE 1980 THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER By Jacqueline Korona Teare A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS School of Journalism 1980 ABSTRACT THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER 3y Jacqueline Korona Teare Three thousand miles west of Hawaii, the tips of volcanic mountains poke through the ocean surface to form the le-square- mile island of Guam. Residents of this island and surrounding island groups are isolated from the rest of the world by distance, time and, for some, by relatively primitive means of communication. Until recently, the only non-military, English-language daily news- paper serving this three million-square-mile section of the world was the Pacific Daily News, one of the 82 publications of the Rochester, New York-based Gannett Co., Inc. This study will trace the history of journalism on Guam, particularly the Pacific Daily News. It will show that the Navy established the daily Navy News during reconstruction efforts follow- ing World War II. That newspaper was sold in l950 to Guamanian civilian Joseph Flores, who sold the newspaper in 1969 to Hawaiian entrepreneur Chinn Ho and his partner. The following year, they sold the newspaper now called the Pacific Daily News, along with their other holdings, to Gannett. Jacqueline Korona Teare This study will also examine the role of the Pacific Daily Ngw§_in its unique community and attempt to assess how the newspaper might better serve its multi-lingual and multi-cultural readership in Guam and throughout Micronesia. -

Pacific Islands Communication Newsletter, August 1973, Vol. 4, No. 1

t '. ilf tonimunIeaUoii .Now¬tIt¬W -West Communication Institute Honolulu, Hawaii SURVEY ON TRAINING FOR PACIFIC ISLAND NEWSPAPERMEN The South Pacific Editors Con- It was recognized that he must be a program was to produce a journalist able to what is inhis rice last year in Fiji agreed that able to demonstrate ability to perform identify happening it development of an efficient and certain skills and solve certain problems, own country, represent clearlyand to his and be '"1xinsjb1e press in the Pacific Islands but the skills and problems objectively people, particu- of traditional ends on solving theproblem of train- had to be identified. larly conscious and sensitivities. the relatively inexperienced On-the-job was favored as the best customary Pacific Island ralists who are producing the way of teaching the basic skills, but no The skills a journalist the was to perform were the con- a spilpers in the region. newspaper had staff or facilities to expected I he East-West Communication conduct training systematically. Short ventional skills but in addition he had to be able to do from titute affirmed its support of the courses in techniques would help everything sweeping alleviate this, but it was thought they the floors to writing editorials. itors' aspirations by inviting :) In McClefland, aNew Zealand jour- should go further, that the objective of (continued, p. and volunteer editor of the Tonga Onlele for two years, onasix-month PRESS CONFERENCE OF THE PACIFIC GETS GOING WHhip to develop a program and ''iii which could be used as basic Pacific press conferences using the entry into the Common Market on Pacific hug for inexperienced Island jour- Peacesat radio satellite system were con- Island trading. -

Blocked Titles - Academic and Public Library Markets Factiva

Blocked Titles - Academic and Public Library Markets Factiva Source Name Source Code Aberdeen American News ABAM Advocate ADVO Akron Beacon Journal AKBJ Alexandria Daily Town Talk ADTT Allentown Morning Call XALL Argus Leader ARGL Asbury Park Press ASPK Asheville Citizen-Times ASHC Baltimore Sun BSUN Battle Creek Enquirer BATL Baxter County Newspapers BAXT Belleville News-Democrat BLND Bellingham Herald XBEL Brandenton Herald BRDH Bucryus Telegraph Forum BTF Burlington Free Press BRFP Centre Daily Times CDPA Charlotte Observer CLTO Chicago Tribune TRIB Chilicothe Gazette CGOH Chronicle-Tribune CHRT Cincinnati Enquirer CINC Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS) CLDG Cochocton Tribune CTOH Columbus Ledger-Enquirer CLEN Contra Costa Times CCT Courier-News XCNW Courier-Post CPST Daily Ledger DLIN Daily News Leader DNLE Daily Press DAIL Daily Record DRNJ Daily Times DTMD Daily Times Adviser DTA Daily World DWLA Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY) DMCR Des Moines Register DMRG Detroit Free Press DFP Detroit News DTNS Duluth News-Tribune DNTR El Paso Times ELPS Florida Today FLTY Fort Collins Coloradoan XFTC Fort Wayne News Sentinel FWNS Fort Worth Star-Telegram FWST Grand Forks Herald XGFH Great Falls Tribune GFTR Green Bay Press-Gazette GBPG Greenville News (SC) GNVL Hartford Courant HFCT Harvard Business Review HRB Harvard Management Update HMU Hattiesburg American HATB Herald Times Reporter HTR Home News Tribune HMTR Honolulu Advertiser XHAD Idaho Statesman BSID Iowa City Press-Citizen PCIA Journal & Courier XJOC Journal-News JNWP Kansas City Star -

Scripps National Spelling

SCRIPPS NATIONAL SPELLING BEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Competition Schedule 1 About Our Program 2 Prizes 3 Rules 4 Competition Flow Chart 8 Twenty Questions (Answered) 10 Statistics: This Year 14 Statistics: Previous Years 15 Champions and Their Winning Words 16 Meet the Spellebrities 18 Spellers and Sponsors 19 Leadership and Year-Round Staff 31 Officials 32 Bee Week Staff 33 what is the origin of the term spelling bee? The word bee, as used in spelling bee, is one of those language puzzles that has never been satisfactorily accounted for. A fairly old and widely used word, it refers to a community social gathering at which friends and neighbors join together in a single activity (sewing, quilting, barn raising, etc.) usually to help one person or family. The earliest known example in print is a spinning bee in 1769. Other early occurrences are husking bee (1816), apple bee (1827), and logging bee (1836). Spelling bee is apparently an American term. It first appeared in print in 1875, but it seems certain that the term was used orally for several years before that. Those who used the word, including most early students of language, assumed that it was the same word as referred to the insect. They thought that this particular meaning had probably been inspired by the obvious similarity between these human gatherings and the industrious, social nature of a beehive. But in recent years scholars have rejected this explanation, suggesting instead that this bee is a completely different word. One possibility is that it comes from the Middle English word bene, which means “a prayer” or “a favor” (and is related to the more familiar word boon). -

Robert A. Underwood 1948–

H former members 1977–2012 H Robert A. Underwood 1948– TERRITORIAL DELEGATE 1993–2003 DEMOCRAT FROM GUAM obert Underwood served five terms as Guam’s the university. During this period, Underwood also earned Delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives an Ed. D. from the University of Southern California before running unsuccessfully for governor. As in 1987 and graduated from Harvard’s Management RGuam’s third Delegate, Underwood continued his two Development Program in 1988.4 Underwood married predecessors’ push for commonwealth status for the Lorraine Aguilar, a teacher, and the couple had five tiny island in the Western Pacific. His experience as an children: Sophia, Roberto, Ricardo, Ramon, and Raphael.5 educator, along with his respect for Guam’s Chamorro In 1992, Underwood left the University of Guam to culture, shaped much of his legislative agenda during his challenge four-term incumbent Ben Blaz in the election time in the House. Using his position to draw attention for Guam’s congressional Delegate. Long active in the to the pressing needs of the territory, Underwood fought debate on Guam’s political status, Underwood was for increased recognition for Guam and for its inclusion in familiar with the issues affecting the island and pledged federally funded programs. “When you’re a small territory, to use his experience in public policy to help Guam at the the nexus of your relationship to the federal government national level.6 He used his strong ties to the community, is the basis for your representation in Washington,” built during his career as an educator, and his familial Underwood noted. -

November 7, 2014 Laura Lovrien Liberty Publishers Services Orbital

November 7, 2014 Laura Lovrien Liberty Publishers Services Orbital Publishing Group P.O. Box 2489 White City, OR 97503 Re: Cease and Desist Distribution of Deceptive Subscription Notices Dear Ms. Lovrien: The undersigned represent the Newspaper Association of America (“NAA”), a nonprofit organization that represents daily newspapers and their multiplatform businesses in the United States and Canada. It has come to our attention that companies operating under various names have been sending subscription renewal notices and new subscription offers to both subscribers and non-subscribers of various NAA member newspapers. These notices falsely imply that they are sent on behalf of a member newspaper and falsely represent that the consumer is obtaining a favorable price. In reality, these notices are not authorized by our member newspapers, and often quote prices that far exceed the actual subscription price. We understand that the companies sending these deceptive subscription renewal notices operate under many different names, but that many of them are subsidiaries or affiliates of Liberty Publishers Services or Orbital Publishing Group, Inc. We have sent this letter to this address because it is cited on many of the deceptive notices. Liberty Publishers Services, Orbital Publishing Group, and their corporate parents, subsidiaries, and other affiliated entities, distributors, assigns, licensees and the respective shareholders, directors, officers, employees and agents of the foregoing, including but not limited to the entities listed in Attachment A (collectively, “Liberty Publishers Services” and/or “Orbital Publishing Group”), are not authorized by us or any of our member newspapers to send these notices. Our member newspapers do not and have not enlisted Liberty Publishers Services or Orbital Publishing Group for this purpose and Liberty Publishers Services and Orbital Publishing Group are not authorized to hold themselves out in any way as agents who can process payments from consumers to purchase subscriptions to our member newspapers. -

2015 Annual Report Company Profile

2015 ANNUAL REPORT COMPANY PROFILE GANNETT IS A LEADING INTERNATIONAL, MULTI-PLATFORM NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY that delivers high-quality, trusted USA TODAY is currently the content where and when consumers nation’s number one publication want to engage with it on virtually in consolidated print and digital any device or digital platform. The circulation, according to the Alliance company’s operations comprise USA for Audited Media’s December 2015 TODAY, 92 local media organizations Publisher’s Statement, with total in the U.S. and Guam, and in the U.K., daily circulation of 4.0 million and Newsquest (the company’s wholly Sunday circulation of 3.9 million, which owned subsidiary). includes daily print, digital replica, digital non-replica and branded Gannett’s vast USA TODAY NETWORK editions. There have been more than is powered by its award-winning 22 million downloads of USA TODAY’s U.S. media organizations, with deep award-winning app on mobile devices roots across the country, and has a and 3.7 million downloads of apps combined reach of more than 100 associated with Gannett’s local million unique visitors monthly. publications and digital platforms. USA TODAY’s national content, which has been a cornerstone of the national Newsquest has more than 150 news and information landscape for local news brands online, mobile more than three decades, is included and in print, and attracts nearly 24 in 36 local daily Gannett publications million unique visitors to its digital and in 23 non-Gannett markets. platforms monthly. Photo: Desair Brown, reader advocacy editor at USA TODAY, records a video segment for usatoday.com. -

GANNETT CO., INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-36097 GANNETT CO., INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 38-3910250 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 7950 Jones Branch Drive, McLean, Virginia 22107-0910 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (703) 854-6000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share GCI The New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). -

USA National

USA National Hartselle Enquirer Alabama Independent, The Newspapers Alexander Islander, The City Outlook Andalusia Star Jacksonville News News Anniston Star Lamar Leader Birmingham News Latino News Birmingham Post-Herald Ledger, The Cullman Times, The Daily Marion Times-Standard Home, The Midsouth Newspapers Daily Mountain Eagle Millbrook News Monroe Decatur Daily Dothan Journal, The Montgomery Eagle Enterprise Ledger, Independent Moundville The Florence Times Daily Times Gadsden Times National Inner City, The Huntsville Times North Jefferson News One Mobile Register Voice Montgomery Advertiser Onlooker, The News Courier, The Opelika- Opp News, The Auburn News Scottsboro Over the Mountain Journal Daily Sentinel Selma Times- Pelican, The Journal Times Daily, The Pickens County Herald Troy Messenger Q S T Publications Tuscaloosa News Red Bay News Valley Times-News, The Samson Ledger Weeklies Abbeville Sand Mountain Reporter, The Herald Advertiser Gleam, South Alabamian, The Southern The Atmore Advance Star, The Auburn Plainsman Speakin' Out News St. Baldwin Times, The Clair News-Aegis St. Clair BirminghamWeekly Times Tallassee Tribune, Blount Countian, The The Boone Newspapers Inc. The Bulletin Centreville Press Cherokee The Randolph Leader County Herald Choctaw Thomasville Times Tri Advocate, The City Ledger Tuskegee Clanton Advertiser News, The Union Clarke County Democrat Springs Herald Cleburne News Vernon Lamar Democrat Conecuh Countian, The Washington County News Corner News Weekly Post, The County Reaper West Alabama Gazette Courier -

Notice of Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case 12/15

17-22445-rdd Doc 18 Filed 03/30/17 Entered 03/31/17 00:22:52 Imaged Certificate of Notice Pg 1 of 40 Information to identify the case: Debtor Metro Newspaper Advertising Services, Inc. EIN 13−1038730 Name United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New York Date case filed for chapter 11 3/27/17 Case number: 17−22445−rdd Official Form 309F (For Corporations or Partnerships) Notice of Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case 12/15 For the debtor listed above, a case has been filed under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. An order for relief has been entered. This notice has important information about the case for creditors, debtors, and trustees, including information about the meeting of creditors and deadlines. Read both pages carefully. The filing of the case imposed an automatic stay against most collection activities. This means that creditors generally may not take action to collect debts from the debtor or the debtor's property. For example, while the stay is in effect, creditors cannot sue, assert a deficiency, repossess property, or otherwise try to collect from the debtor. Creditors cannot demand repayment from the debtor by mail, phone, or otherwise. Creditors who violate the stay can be required to pay actual and punitive damages and attorney's fees. Confirmation of a chapter 11 plan may result in a discharge of debt. A creditor who wants to have a particular debt excepted from discharge may be required to file a complaint in the bankruptcy clerk's office within the deadline specified in this notice. (See line 11 below for more information.) To protect your rights, consult an attorney. -

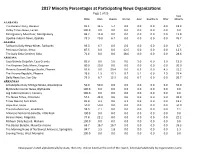

2017 Summary Report for Each News Organization.Xlsx

2017 Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations Page 1 of 25 Total White Black Hispanic Am. Ind. Asian Haw/Pac. Is Other Minority ALABAMA The Decatur Daily, Decatur 81.1 13.5 5.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.9 Valley Times-News, Lanett 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery 84.2 15.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 15.8 Opelika-Auburn News, Opelika 73.3 20.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 26.7 ALASKA Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks 93.3 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 6.7 Peninsula Clarion, Kenai 87.5 0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 12.5 The Daily Sitka Sentinel, Sitka 71.4 0.0 0.0 28.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 28.6 ARIZONA Casa Grande Dispatch, Casa Grande 85.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 15.0 The Kingman Daily Miner, Kingman 80.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Phoenix Gannett Design Studio, Phoenix 65.6 0.0 20.4 0.0 6.5 0.0 4.3 31.2 The Arizona Republic, Phoenix 76.6 1.5 13.1 0.7 5.1 0.0 2.9 23.4 Daily News-Sun, Sun City 73.3 6.7 13.3 0.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 26.7 ARKANSAS Arkadelphia Daily Siftings Herald, Arkadelphia 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 Blytheville Courier News, Blytheville 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Log Cabin Democrat, Conway 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The News-Times, El Dorado 57.1 42.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 42.9 Times Record, Fort Smith 81.8 9.1 0.0 9.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.2 Hope Star, Hope 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 The Jonesboro Sun, Jonesboro 92.9 7.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 7.1 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Banner-News, Magnolia 77.8 22.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 22.2 Malvern Daily Record, Malvern 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Baxter Bulletin, Mountain Home 66.7 16.7 16.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 33.3 The Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, Springdale 94.7 3.5 1.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 5.3 Evening Times, West Memphis 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Newspapers listed alphabetically by state, then city. -

2008 Annual Report Annual 2008

08-COVERFINALRev2-25:Layout 1 2/25/09 5:05 PM Page 1 7950 JONES BRANCH DR. INC. • GANNETT REPORT CO., 2008 ANNUAL MCLEAN, VA 22107 WWW.GANNETT.COM s 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 08-COVERFINALRev2-25:Layout 1 2/25/09 5:05 PM Page 2 Table of Contents Shareholder Services GANNETT STOCK THIS REPORT WAS WRITTEN Gannett Co., Inc. shares are traded on the New York Stock Exchange with the symbol GCI. The AND PRODUCED BY EMPLOYEES 2008 Financial Summary . 1 OF GANNETT. company’s transfer agent and registrar is Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. General inquiries and requests Letter to Shareholders . 2 for enrollment materials for the programs described below should be directed to Wells Fargo Vice President and Controller Board of Directors . 7 Shareowner Services, P.O. Box 64854, St. Paul, MN 55164-0854 or by telephone at 1-800-778-3299 George Gavagan or at www.wellsfargo.com/shareownerservices. Company and Divisional Officers . 8 Director of Consolidations and DIVIDEND REINVESTMENT PLAN Financial Reporting The Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) provides Gannett shareholders the opportunity to Cam McClelland purchase additional shares of the company’s common stock free of brokerage fees or service Form 10-K charges through automatic reinvestment of dividends and optional cash payments. Cash Vice President/Corporate payments may range from a minimum of $10 to a maximum of $5,000 per month. Communications Tara Connell AUTOMATIC CASH INVESTMENT SERVICE FOR THE DRP Senior Manager/Publications This service provides a convenient, no-cost method of having money automatically withdrawn Laura Dalton from your checking or savings account each month and invested in Gannett stock through your DRP account.