Depression-Era Worker at a Carbon Black Plant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Lives

TEACHING WITH PRIMARY SOURCES Children’s Lives: Comparing Long Ago to Today How have children’s lives changed over time? Too often we look back at the way people lived and evaluate the past in terms of the technology that dominates our lives today. We ask: Imagine life without automobiles or electric lights or running water. No refrigerators, washing machines, radio, television, or movies? No computers, CDs, cell phones or credit cards. How did they survive? If that is how you want to approach the past, ask yourself this: what future inventions do we not have will make Iowans of the future look back and wonder how made it through the day? Children’s Lives in the Home A better approach is to look at how people of any age adapted to what they had around them. For children, the best place to start is to look at their homes. For children on the Iowa frontier, most homes had to produce nearly all their own needs. Children learned to contribute to the family’s survival at an early age. Most Iowans lived on farms that raised much of their own food, and children became an important part of the family team. They gathered eggs, worked in the garden, carried in wood and water and perhaps cared for younger brothers and sisters. As girls got older, they learned to cook, sew, preserve food for the winter, do the washing and tend to the sick. Boys helped their father with the livestock, planting and harvest, hunting, and maintenance of buildings and fences. -

Las Relaciones Públicas, La Comunicación Visual Y El Mito Del Capitalismo Transnacional (1943-1950)

Historia Contemporánea, 2021, 66, 493-522 https://doi.org/10.1387/hc.21124 HC ISSN 1130-2402 – eISSN 2340-0277 LAS RELACIONES PÚBLICAS, LA COMUNICACIÓN VISUAL Y EL MITO DEL CAPITALISMO TRANSNACIONAL (1943-1950) PUBLIC RELATIONS, VISUAL COMMUNICATION AND THE MYTH OF TRANSNATIONAL CAPITALISM (1943-1950) Edward Goyeneche-Gómez* Universidad de La Sabana. Colombia RESUMEN: El artículo estudia las transformaciones de las relaciones públicas (PR) interna- cionales, entre 1943 y 1950, en el contexto de la industria privada norteamericana, vinculado al desarrollo del Proyecto Fotográfico de la Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), que buscaba la construcción de un nuevo mito sobre el capitalismo transnacional que conectara la economía, la sociedad y la cultura, más allá de los estados nacionales, en medio de una crisis discursiva gene- rada por la Segunda Guerra Mundial y las ideologías populistas y folcloristas dominantes. Se de- muestra que esa multinacional, buscando enfrentar una crisis de imagen, revolucionó el campo de las relaciones públicas, a partir del uso de un aparato de comunicación visual denominado foto- grafía documental industrial, que permitiría conectar de manera inédita y contradictoria, en torno a la historia del petróleo, a Estados Unidos con sociedades de todo el globo, principalmente con América Latina. Palabras claVE: Relaciones públicas; Industria petrolera; Fotografía documental; Capita- lismo. ABSTRACT: The article studies the transformations of international public relations (PR), be- tween 1943 and 1950, in the context of North American private industry, linked to the development of the Photographic Project of the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), which sought the construc- tion of a new myth about transnational capitalism, which will connect the economy, society and culture, beyond national states, amid a discursive crisis generated by World War II and the domi- nant populist and folklorist ideologies. -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944. -

The Bitter Years: 1935-1941 Rural America As Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration

The bitter years: 1935-1941 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration. Edited by Edward Steichen Author United States. Farm Security Administration Date 1962 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3433 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE BITTER YEARS 1.935-1 94 1 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration Edited by Edward Steichen The Museum of Modern Art New York The Bitter Years: 1935-1941 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration Edited by Edward Steichen The Museum of Modern Art, New Y ork Distributed by Doubleday and Co., Inc., Garden City, N.5 . To salute one of the proudest achievements in the history of photography, this book and the exhibition on which it is based are dedicated by Edward Steichen to ROY E. STRYKER who organized and directed the Photographic Unit of the Farm Security Administration and to his photo graphers : Paul Carter, John Collier, Jr., Jack Delano, Walker Evans, Theo Jung, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, and Marion Post Wolcott. © 1962, The Museumof Modern Art, JVew York Library of CongressCatalogue Card JVumber:62-22096 Printed in the United States of America I believe it is good at this time to be reminded of It was clear to those of us who had responsibility for those "Bitter Years" and to bring them into the con the relief of distress among farmers during the Great sciousness of a new generation which has problems of Depression and during the following years of drought, its own, but is largely unaware of the endurance and that we were passing through an experience of fortitude that made the emergence from the Great American life that was unique. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Forgotten Man: the Rhetorical Construction of Class and Classlessness in Depression Era Media

The Forgotten Man: The Rhetorical Construction of Class and Classlessness in Depression Era Media A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts of and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lee A. Gray November 2003 @ 2003 Lee A. Gray All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled The Forgotten Man: The Rhetorical Construction of Class and Classlessness in Depression Era Media By Lee A. Gray has been approved for the Individual Interdisciplinary Program and The College of Arts and Sciences by Katherine Jellison Associate Professor, History Raymie E. McKerrow Professor, Communication Studies Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Gray, Lee A. Ph.D. November 2003. History/Individual Interdisciplinary Program The Forgotten Man: The Rhetorical Construction of Class and Classlessness in Depression Era Media (206 pp.) Co-Directors of Dissertation: Katherine Jellison and Raymie McKerrow The following study is an analysis of visual and narrative cultural discourses during the interwar years of 1920-1941. These years, specifically those of the 1930s, represent a significant transitional point in American history regarding cultural identity and social class formation. This study seeks to present one profile of how the use of media contributed to a mythic cultural identity of the United States as both classless and middle-class simultaneously. The analysis is interdisciplinary by design and purports to highlight interaction between visual and oral rhetorical strategies used to construct and support the complex myths of class as they formed during this period in American history. I begin my argument with Franklin D. -

Papers of John Vachon

John Vachon A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Connie L. Cartledge Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2006 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2007 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms007030 Collection Summary Title: Papers of John Vachon Span Dates: 1913-1995 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1935-1959) ID No.: MSS85246 Creator: Vachon, John, 1914-1975 Extent: 4,000 items; 12 containers; 4.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Photographer. Correspondence, family papers, writings, and miscellaneous material relating primarily to Vachon’s career as a photographer with the Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information, and Look magazine. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Names: Vachon, John, 1914-1975 Lange, Dorothea Monroe, Marilyn, 1926-1962 Rothstein, Arthur, 1915- Stryker, Roy Emerson, 1893-1975 Vachon, Ann O'Hara--Correspondence Vachon, Millicent--Correspondence Williams, Tennessee, 1911-1983. United States. Army United States. Farm Security Administration United States. Office of War Information Catholic University of America--Students Standard Oil Company of -

Sorrow-Hope Guide to Places.Pdf

Times of Sorrow & Hope GUIDE TO PLACES PHOTOGRAPHED IN THE ON-LINE CATALOG A Beaver Falls Canton and Canton vicinity Aliquippa January , Jack Delano April , Paul Carter July , Arthur Rothstein January , John Vachon Cardiff January , Jack Delano Bedford County September , Jack Delano January , John Vachon September , Arthur Rothstein Carlisle (army base and city) West Aliquippa December , Arthur Rothstein June , John Vachon January , Jack Delano Bethlehem February , Marjory Collins January , John Vachon , Paul Carter Carpenterville West Aliquippa vicinity ,November ,December , No date, Arthur Rothstein January , Jack Delano Walker Evans Catasauqua Allegheny Mountains March , Walker Evans , U.S. Army Air Forces photograph June , Summer , April , Paul Carter [Note: See the “Other and Unidenti- Arthur Rothstein May , Howard Liberman fied Photographs” section of the Allegheny National Forest May , Howard Hollem catalog.] , E. S. Shipp Birdsboro vicinity Chaneysville October ,H.C.Frayer August , Sheldon Dick December , Arthur Rothstein Allentown Blue Ball and Blue Ball vicinity Chester Between and , U.S. Army March , John Collier [?], Spring , Paul Vanderbilt photograph [Note: See the “Other Brackenridge June , “Kelly,”U.S. Maritime and Unidentified Photographs” Between and , Alfred Palmer Commission photograph [Note: See section of the catalog.] [?], Alfred Palmer the “Other and Unidentified Pho- Ambler Bradford tographs” section of the catalog.] Summer , Paul Vanderbilt September , Alfred Palmer Cheyney Ambridge Bridgewater July , no photographer -

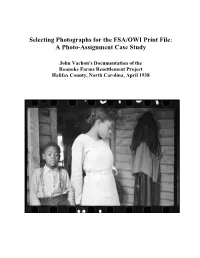

Selecting Photographs for the FSA/OWI Print File: a Photo-Assignment Case Study

Selecting Photographs for the FSA/OWI Print File: A Photo-Assignment Case Study John Vachon's Documentation of the Roanoke Farms Resettlement Project Halifax County, North Carolina, April 1938 Selecting Photographs for the FSA/OWI Print File: A Photo-Assignment Case Study Selecting Photographs for the FSA/OWI Print File: A Photo-Assignment Case Study John Vachon's Documentation of the Roanoke Farms Resettlement Project Halifax County, North Carolina, April 1938 Carl Fleischhauer 25 June 2020 Table of Contents 1. What is this document? ................................................................................................... 3 2. Photo assignments .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Building the section's print file ....................................................................................... 5 4. Killing negatives, retaining negatives ............................................................................. 6 Sidebar: The FSA/OWI Photo Selection Process ............................................................ 7 5. Caption sheets and the identification of killed photographs ........................................... 9 Sidebar: Identifying and Counting Killed, Selected, and Hole-Punched 35mm Negatives ....................................................................................................................... 12 6. Overview of the findings ............................................................................................. -

V61i05p174-195.Pdf

Lhmmdrns` IN THE B`ldq`ÒrDxd 1935Ð1943 Alan Trachtenberg aZmp^dghph_]Zbereb_^bgma^Ngbm^] lbhgËZg]Êma^Mabkmb^lËbgpZrlfhk^]bo^kl^%\hfie^q% LmZm^l]nkbg`ma^@k^Zm=^ik^llbhgh_ma^ Zg]i^klhgZemaZgma^lm^k^hmri^]^qi^\mZmbhgh_ln__^k& *2,)l\hf^leZk`^er_khfZg^qmkZhk]b& bg`Zg]Z[c^\mbhgZ\khllma^eZg]'+ gZkr\hee^\mbhgh_iahmh`kZialfZ]^_hk Hg\^rhnhi^gma^Öe^%ma^k^blZepZrlfhk^mhl^^% WZ`ho^kgf^gmZ`^g\r%ma^?ZkfL^\nkbmr:]fbgblmkZmbhg hma^kpZrlh_ehhdbg`Zg]k^Z]bg`'Ahnl^]bg_hnk& !?L:"%_khf*2,/mh*2-,'<hg\^kg^]ZmÖklmpbmama^ ]kZp^klm^^e\Z[bg^mlbgma^IkbgmlZg]Iahmh`kZial ieb`amh__Zkf^kl%laZk^\khii^kl%Zg]fb`kZgm_Zkfphkd& khhfh_ma^Eb[kZkrh_<hg`k^ll%ma^\hee^\mbhgÉÊma^ ^kl%ma^iahmh`kZiab\ikhc^\mlhhg[^\Zf^ZgZmbhgZe Öe^ËÉbg\en]^likbgml%bfZ`^l%Zg]g^`Zmbo^lfZ]^bg ikh`kZfh_^ib\Zg]^ih\aZeikhihkmbhgl'Ma^k^lnempZl *2,._hkma^K^l^mme^f^gm:]fbgblmkZmbhg!K:"Zg]ma^g ZÖe^h_00%)))ikbgmlZg]fZgrfhk^bfZ`^lZg]g^`Z& _hkma^?L:%bg\hgg^\mbhgpbmaG^p=^Zeiheb\rZbf^]Zm mbo^l_khfoZkbhnllhnk\^l%hk`Zgbs^][rln[c^\ma^Z]bg`l k^obobg`Zg]k^lmkn\mnkbg`:f^kb\ZgZ`kb\nemnk^',Bgma^ Zg]`^h`kZiab\Zek^`bhgl'* ikh\^ll%ma^ikhc^\m^qiZg]^]bgmhZ`^g^kZe^magheh`r :Fbgg^lhmZlmhkraZlZek^Z]r[^^g^qmkZ\m^]_khf h_^o^kr]Zreb_^%bg\en]bg`\bmb^lZg]nk[Zgk^`bhgl'GZ& mabl`k^ZmZk\abo^3Ib\mnkbg`Fbgg^lhmZ%*2,/È*2-,% mbhgZebgl\hi^%bmpZlZelhgZmbhgZebgbmlZbfmhb]^gmb_r ^]bm^][rKh[^kmE'K^b]':gbgoZenZ[e^]h\nf^gmh_ma^ paZmpZlngbjn^Zg]]blmbg\mbo^Z[hnmma^gZmbhg'Pa^g ehhdh_Fbgg^lhmZÍlÊ`k^Zm^lm`^g^kZmbhgË]nkbg`ma^aZk] pZk[khd^hnmbg>nkhi^Zg]bml^^f^]ebd^ermaZmma^ mbf^l[^_hk^ma^pZk%mabl[hhdikhob]^lZ[Zl^ebg^_hk Ngbm^]LmZm^lphne][^\hf^bgoheo^]%ma^H_Ö\^h_PZk -

(IMLS) Museums for America to Increase Public Access to Work from LOOK Magazine Staff Photographer John Vachon

Museum of the City of New York receives $185,423 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America to increase public access to work from LOOK Magazine staff photographer John Vachon (New York, NY | October 2018) - The Museum of the City of New York is honored to announce that it has been awarded a $185,423 Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services Museums for America in the cateGory of Collections Stewardship to diGitize work from LOOK Magazine staff photoGrapher John Vachon. This project will diGitize approximately 18,500 photoGraphs from 54 of Vachon’s assiGnments over the course of his 25-year career with LOOK. This project is part of an onGoinG effort to provide online access to the Museum’s LOOK Collection, which includes approximately 200,000 photoGraphs related to 2,242 stories from 41 different photoGraphers. These photoGraphs were taken between 1938 and 1968 and vividly document the cultural transformation of America from World War II throuGh the Cold War era. With this Generous support from the Institute, the Museum will make this important collection freely accessible to the public. Founded in 1937 by Des Moines, Iowa newspaperman Gardner Cowles, LOOK focused a lens on the lives of individuals, usinG personal stories to narrate the nuanced political, social, and cultural issues of the day, rather than takinG the broader documentary approach of a publication like Life. John Vachon—who made his name as a photoGrapher workinG for Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration (FSA) durinG the Great Depression—was known for his technical skill anddramatic composition. -

Discursive Productions by Standard Oil New Jersey Post WWII

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Oil, space, and national imaginaries : discursive productions by standard oil New Jersey post WWII. Michael Poindexter University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Poindexter, Michael, "Oil, space, and national imaginaries : discursive productions by standard oil New Jersey post WWII." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2653. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2653 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OIL, SPACE, AND NATIONAL IMAGINARIES: DISCURSIVE PRODUCTIONS BY STANDARD OIL NEW JERSEY POST WWII by Michael Poindexter B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Applied Geography Department of Geography and Geosciences University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2017 OIL, SPACE, AND NATIONAL IMAGINARIES: DISCURSIVE PRODUCTIONS BY STANDARD OIL NEW JERSEY POST WWII By Michael Poindexter B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 A Thesis Approved on April 26, 2017 by the following Thesis Committee: __________________________________ Dr. Margath Walker __________________________________ Dr.