PRELIMINARY RESULTS of the SURVEY on PERSONS with DISABILITIES (Pwds) CONDUCTED in SELECTED METRO MANILA CITIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2000-20 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. June 2000 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Urban Landscape: Metro Manila and its 2 Peripheral Areas The Physical Environment 2 Pattern of Urban Settlement 4 Pattern of Land Ownership 9 3. The Institutional Environment: Urban Management and Land Use Planning 11 The Historical Precedents 11 Government Efforts Toward Comprehensive 14 Urban Planning The Development Control Process: 17 Centralization vs. Decentralization 4. Institutional Arrangements: 28 Procedural Short-cuts and Relational Contracting Sources of Transaction Costs in the Urban 28 Real Estate Market Grease/Speed Money 33 Procedural Short-cuts 36 5. -

1 Introduction

Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION The Philippines, through RBCO-DENR had defined 20 major river basins spread all over the country. These basins are defined as major because of their importance, serving as lifeblood and driver of the economy of communities inside and outside the basins. One of these river basins is the Marikina River Basin (Figure 1). Figure 1 Marikina River Basin Map 1 | P a g e Formulation of an Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Marikina River Basin VOLUME 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Marikina River Basin is currently not in its best of condition. Just like other river basins of the Philippines, MRB is faced with problems. These include: a) rapid urban development and rapid increase in population and the consequent excessive and indiscriminate discharge of pollutants and wastes which are; b) Improper land use management and increase in conflicts over land uses and allocation; c) Rapidly depleting water resources and consequent conflicts over water use and allocation; and e) lack of capacity and resources of stakeholders and responsible organizations to pursue appropriate developmental solutions. The consequence of the confluence of the above problems is the decline in the ability of the river basin to provide the goods and services it should ideally provide if it were in desirable state or condition. This is further specifically manifested in its lack of ability to provide the service of preventing or reducing floods in the lower catchments of the basin. There is rising trend in occurrence of floods, water pollution and water induced disasters within and in the lower catchments of the basin. -

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO MANILA ................................................... 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ 5 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 5 DIET ............................................................................................ 5 MONEY ........................................................................................ 6 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................... 7 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 7 VISA ............................................................................................. 8 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 9 LANGUAGE LEARNING ............................................................. 9 HOST FAMILY .......................................................................... 10 EXCURSIONS ............................................................................ 10 VISITORS .................................................................................. 10 ACCOMODATIONS ................................................................... 11 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT PHILIPPINES ................................ 11 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 13 NOTE: Information is subject to -

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W

Cities Development Initiative for Asia P R O J E C T O V E R V I E W Country: P H I L I P P I N E S Status: Key Sector(s): COMPLETED FLOOD AND DRAINAGE MANAGEMENT City: VALENZUELA Application approved: 20/JAN/2014 P R O P O N E N T S Geography and Population Valenzuela City Government Mayor Rex Gatchalian Area: 44.59 km2 City Hall, MacArthur Highway, City Mayor Barangay Karuhatan, Valenzuela City, City Government of Valenzuela Population: 598,968 Metropolitan Manila 1400 The city of Valenzuela is located 14km north of Phone: (+63) 2 352 1000 Phone: (+63) 291 3069 Manila, the capital city of Website: www.valenzuela.gov.ph the Philippines. It is one of the 16 highly urbanized Central State Partner Other Partners cities of Metropolitant National Economic Development DPWH, Maynilad Manila. Due to its strategic Authority (NEDA) location at the northern K E Y C I T Y D E V E L O P M E N T I S S U E S most part of Metro Manila, and the migration of The overall city's development plans focus on the following areas: people, Valenzuela has Valenzuela is located in an area that has 16% frequency of tropical cyclones grown into a major also, a third of the city, particularly the western side is composed of swampy economic and industrial areas that are not only one to five meters above the sea level; this greatly center. makes the city particularly the improverished areas susceptible to flooding. -

Business Directory Commercial Name Business Address Contact No

Republic of the Philippines Muntinlupa City Business Permit and Licensing Office BUSINESS DIRECTORY COMMERCIAL NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTACT NO. 12-SFI COMMODITIES INC. 5/F RICHVILLE CORP TOWER MBP ALABANG 8214862 158 BOUTIQUE (DESIGNER`S G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG BOULEVARD) 158 DESIGNER`S BLVD G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG 890-8034/0. EXTENSION 1902 SOFTWARE 15/F ASIAN STAR BUILDING ASEAN DRIVE CORNER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION SINGAPURA LANE FCC ALABANG 3ARKITEKTURA INC KM 21 U-3A CAPRI CONDO WSR CUPANG 851-6275 7 MARCELS CLOTHING INC.- LEVEL 2 2040.1 & 2040.2 FESTIVAL SUPERMALL 8285250 VANS FESTIVAL ALABANG 7-ELEVEN RIZAL ST CORNER NATIONAL ROAD POBLACION 724441/091658 36764 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE EAST SERVICE ROAD ALABANG SERVICE ROAD (BESIDE STORE PETRON) 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE G/F REPUBLICA BLDG. MONTILLANO ST. ALABANG 705-5243 STORE MUNT. 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE UNIT 1 SOUTH STATION ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD 5530280 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE 452 CIVIC PRIME COND. FCC ALABANG 7-ELEVEN/FOODSTORE MOLINA ST COR SOUTH SUPERH-WAY ALABANG 7MARCELS CLOTHING, INC. UNIT 2017-2018 G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER 8128861 MUNTINLUPA CITY 88 SOUTH POINTER INC. UNIT 2,3,4 YELLOW BLDG. SOUTH STATION FILINVEST 724-6096 (PADIS POINT) ALABANG A & C IMPORT EXPORT E RODRIGUEZ AVE TUNASAN 8171586/84227 66/0927- 7240300 A/X ARMANI EXCHANGE G/F CORTE DE LAS PALMAS ALAB TOWN CENTER 8261015/09124 AYALA ALABANG 350227 AAI WORLDWIDE LOGISTICS KM.20 WEST SERV.RD. COR. VILLONGCO ST CUPANG 772-9400/822- INC 5241 AAPI REALTY CORPORATION KM22 EAST SERV RD SSHW CUPANG 8507490/85073 36 AB MAURI PHILIPPINES INC. -

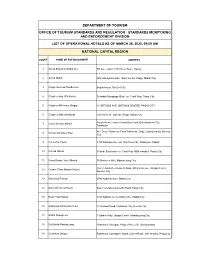

Standards Monitoring and Enforcement Division List Of

DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM OFFICE OF TOURISM STANDARDS AND REGULATION - STANDARDS MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT DIVISION LIST OF OPERATIONAL HOTELS AS OF MARCH 26, 2020, 09:00 AM NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION COUNT NAME OF ESTABLISHMENT ADDRESS 1 Ascott Bonifacio Global City 5th ave. Corner 28th Street, BGC, Taguig 2 Ascott Makati Glorietta Ayala Center, San Lorenzo Village, Makati City 3 Cirque Serviced Residences Bagumbayan, Quezon City 4 Citadines Bay City Manila Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. cor. Coral Way, Pasay City 5 Citadines Millenium Ortigas 11 ORTIGAS AVE. ORTIGAS CENTER, PASIG CITY 6 Citadines Salcedo Makati 148 Valero St. Salcedo Village, Makati city Asean Avenue corner Roxas Boulevard, Entertainment City, 7 City of Dreams Manila Paranaque #61 Scout Tobias cor Scout Rallos sts., Brgy. Laging Handa, Quezon 8 Cocoon Boutique Hotel City 9 Connector Hostel 8459 Kalayaan Ave. cor. Don Pedro St., POblacion, Makati 10 Conrad Manila Seaside Boulevard cor. Coral Way MOA complex, Pasay City 11 Cross Roads Hostel Manila 76 Mariveles Hills, Mandaluyong City Corner Asian Development Bank, Ortigas Avenue, Ortigas Center, 12 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Quezon City 13 Discovery Primea 6749 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 14 Domestic Guest House Salem Complex Domestic Road, Pasay City 15 Dusit Thani Manila 1223 Epifanio de los Santos Ave, Makati City 16 Eastwood Richmonde Hotel 17 Orchard Road, Eastwood City, Quezon City 17 EDSA Shangri-La 1 Garden Way, Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City 18 Go Hotels Mandaluyong Robinsons Cybergate Plaza, Pioneer St., Mandaluyong 19 Go Hotels Ortigas Robinsons Cyberspace Alpha, Garnet Road., San Antonio, Pasig City 20 Gran Prix Manila Hotel 1325 A Mabini St., Ermita, Manila 21 Herald Suites 2168 Chino Roces Ave. -

COVID-19 Government Hotlines

COVID-19 Advisory COVID-19-Related Government Hotlines Department of Health (DOH) 02-894-COVID (02-894-26843); 1555 (PLDT, Smart, Sun, and TNT Subscribers) Philippine Red Cross Hotline 1158 Metro Manila Emergency COVID-19 Hotlines Caloocan City 5310-6972 / 0947-883-4430 Manila 8527-5174 / 0961-062-7013 Malabon City 0917-986-3823 Makati City 168 / 8870-1959-59 Navotas City 8281-1111 Mandaluyong City 0916-255-8130 / 0961-571-6959 Valenzuela City 8352-5000 / 8292-1405 San Juan City 8655-8683 / 7949-8359 Pasig City 8643-0000 Muntinlupa City 0977-240-5218 / 0977-240-5217 Municipality of Pateros 8642-5159 Paranaque City 8820-7783 Marikina City 161 / 0945-517-6926 Las Pinas City 8994-5782 / 0977-672-6211 Taguig City 0966-419-4510 / 8628-3449 Pasay City 0956-7786253 / 0908-9937024 Quezon City 122 Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) (+632) 8807-2631 Department of the Interior and Local (+632) 8876-3444 local 8806 ; Government (DILG) Emergency 8810 to monitor the implementation of directives and Operations Center Hotline measures against COVID-19 in LGUs Department of Trade and Industry 0926-612-6728 (Text/Viber) DTI Officer of the Day COVID Rapid Response Team deployed in NDRRMC Camp Aguinaldo Other Government Hotlines Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) (+632) 8708.77.01 Email: [email protected] Credit Information Corporation (CIC) Email: [email protected] Social Security System (SSS) Trunkline: (+632) 8920-6401 Call Center: (+632) 8920-6446 to 55 IVRS: (+632) 7917-7777 Toll Free: 1-800-10-2255777 Email: [email protected] -

IFC in the Philippines Creating Opportunity Where It’S Needed Most

EAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC IFC in the Philippines Creating Opportunity Where It’s Needed Most IFC supports the Philippines’ sustainable development by helping attract international investors to sectors such as infrastructure and public utilities, financial institutions, and agribusinesses. We provide loans and equity investments to private sector companies, including small and medium enterprises with growth potential, and mobilize financing from other sources. We advise firms and the government on how to enhance businesses’ competitiveness. Since 1962, IFC has invested more than $3 billion in equity and loans for more than 100 private sector companies. We have expanded access to finance and infrastructure, facilitated public-private partnerships, improved the investment climate, mitigated climate change, and supported agribusinesses. IFC’s unique financing and advisory products combine global expertise with local knowledge, maximizing investment returns and social benefits. EAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Mitigating Climate Change • IFC helps scale up lending for projects in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and climate-change mitigation by advising and providing risk guarantees to our partner banks to support their loans. • We are supporting a 180-megawatt solar-and-biomass plant investment on the island of Negros in central Philippines. • To promote energy efficiency, IFC supported Mandaluyong City in Metro Manila in drafting a green-building ordinance that requires new buildings to adopt environmentally friendly features. Supporting Public-Private Supporting Agribusiness Expanding Financing Partnership Projects • The World Bank Group supports • IFC supports banks to • IFC helps the government and agribusiness investments in expand their lending to private investors collaborate on the Bangsamoro region in farmers and micro, small, financing and executing major southern Philippines to promote and women-led enterprises. -

The Ideology of the Dual City: the Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila

bs_bs_banner Volume 37.1 January 2013 165–85 International Journal of Urban and Regional Research DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01100.x The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila MARCO GARRIDO Abstractijur_1100 165..185 Postcolonial cities are dual cities not just because of global market forces, but also because of ideological currents operating through local real-estate markets — currents inculcated during the colonial period and adapted to the postcolonial one. Following Abidin Kusno, we may speak of the ideological continuity behind globalization in the continuing hold of a modernist ethic, not only on the imagination of planners and builders but on the preferences of elite consumers for exclusive spaces. Most of the scholarly work considering the spatial impact of corporate-led urban development has situated the phenomenon in the ‘global’ era — to the extent that the spatial patterns resulting from such development appear wholly the outcome of contemporary globalization. The case of Makati City belies this periodization. By examining the development of a corporate master-planned new city in the 1950s rather than the 1990s, we can achieve a better appreciation of the influence of an enduring ideology — a modernist ethic — in shaping the duality of Makati. The most obvious thing in some parts of Greater Manila is that the city is Little America, New York, especially so in the new exurbia of Makati where handsome high-rise buildings, supermarkets, apartment-hotels and shopping centers flourish in a setting that could well be Palm Beach or Beverly Hills. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management

Progress Report EMI Topical Report TR-07-01 Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative A member of the U.N. Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction 3cd Program Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management A Case Study of Metro Manila September 2006 Copyright © 2007 EMI. Permission to use this document is granted provided that the copyright notice appears in all reproductions and that both the copyright and this permission notice appear, and use of document or parts thereof is for educational, informational, and non-commercial or personal use only. EMI must be acknowledged in all cases as the source when reproducing any part of this publication. Opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect those of the participating agencies and organizations. Report prepared by Jeannette Fernandez, Shirley Mattingly, Fouad Bendimerad and Omar D. Cardona Dr. Martha-Liliana Carreño, Researcher (CIMNE, UPC) Ms. Jeannette Fernandez, Project Manager (EMI/PDC) Layout and Cover Design: Kristoffer Berse Printed in the Philippines by EMI An international, not-for-profi t, scientifi c organization dedicated to disaster risk reduction of the world’s megacities EMI 2F Puno Bldg. Annex, 47 Kalayaan Ave., Diliman Quezon City 1101, Philippines T/F: +63-2-9279643; T: +63-2-4334074 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.emi-megacities.org 3cd Program EMI Topical Report TR-07-01 Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management A Case Study of Metro Manila By Jeannette Fernandez, Shirley Mattingly, Fouad Bendimerad and Omar D. Cardona Contributors Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative, EMI Ms.