The Architecture of Artificial Gravity: Theory, Form, and Function in the High Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galaktika Group: Orbital City «EFIR» «Ethereal Dwelling» Space Colony Concept by Tsiolkovsky

Galaktika group: Orbital city «EFIR» «ethereal dwelling» space colony concept by tsiolkovsky BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CONSTRUCTING A SPACE COLONY UPON THE CONCEPT BY K.E. TSIOLKOVSKY: IN-SPACE ASSEMBLING MANKIND WILL NOT FOREVER REMAIN ON EARTH, BUT IN THE PURSUIT OF LIGHT AND SPACE WILL FIRST USING MATERIALS FROM PLANETS AND ASTEROIDS TIMIDLY EMERGE FROM THE BOUNDS OF THE ATMOSPHERE, AND THEN ADVANCE UNTIL HE HAS CONQUERED THE WHOLE ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY OF CIRCUMSOLAR SPACE. PLANTS CULTIVATION HE PRESENTED HIS RESEARCHES IN THE BOOKS: BEYOND THE PLANET EARTH, BIOLOGICAL LIFE IN COSMOS, ETHEREAL ISLAND, ETC. COLONY CONCEPTS [SHORT] REVIEW BERNAL'S SPHERE, STANFORD TORUS, O’NEILL’S CYLINDER BERNAL’S SPHERE STANFORD TORUS O’NEILL’S CYLINDER JOHN DESMOND BERNAL 1929 POPULATION: STUDENTS OF THE STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1975 GERARD K. O'NEILL, 1979 POPULATION: 20 MLN. 20—30 THOUSAND INHABITANTS DIAMETER POPULATION: 10 THND. AND MORE INHABITANTS INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF CYLINDERS: 6.4 KM ABOUT 16 KM DIAMETER1.8KM AND MORE LENGTH OF CYLINDERS: 32 KM ORBITAL CITY «EFIR» scheme and characteristics TOP VIEW residential torus ASSEMBLY DOCK radiators electric power station elevator 10,000 INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF TORUS – 2 KILOMETRES variable gravity module MASS OF ORBITAL CITY – 25 MLN. TONS RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA RESIDENTIAL AREA CHARACTERISTICS DIAMETER OF TORUS - 2 KILOMETRES ROTATION PERIOD - ONE FULL-CIRCLE TURN PER 63 SECONDS RESIDENTIAL AREA WIDTH - 300 METERS RESIDENTIAL AREA HEIGHT - 150 METERS AREA OF RESIDENTIAL ZONE - 200 HA MAXIMUM POPULATION - 10-40 THOUSAND DESIGNED POPULATION DENSITY IS 50 PEOPLE/HA TO 200 PEOPLE/HA RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA LOGISTICS transport plans for passengers and cargoes ORBITAL CITY AT THE LAGRANGIAN POINT INTERPLANETARY 25 MLN. -

General Issue

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOLUME 72 NO.5 MAY 2019 General issue A REACTION DRIVE Powered by External Dynamic Pressure Jeffrey K. Greason DOCKING WITH ROTATING SPACE SYSTEMS Mark Hempsell MARTIAN DUST: the Formation, Composition, Toxicology, Astronaut Exposure Health Risks and Measures to Mitigate Exposure John Cain THE CONCEPT OF A LOW COST SPACE MISSION to Measure “Big G” Roger Longstaff www.bis-space.com ISSN 0007-084X PUBLICATION DATE: 26 JULY 2019 Submitting papers International Advisory Board to JBIS JBIS welcomes the submission of technical Rachel Armstrong, Newcastle University, UK papers for publication dealing with technical Peter Bainum, Howard University, USA reviews, research, technology and engineering in astronautics and related fields. Stephen Baxter, Science & Science Fiction Writer, UK James Benford, Microwave Sciences, California, USA Text should be: James Biggs, The University of Strathclyde, UK ■ As concise as the content allows – typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers (Technical Notes) Anu Bowman, Foundation for Enterprise Development, California, USA will also be considered; longer papers will only Gerald Cleaver, Baylor University, USA be considered in exceptional circumstances – for Charles Cockell, University of Edinburgh, UK example, in the case of a major subject review. Ian A. Crawford, Birkbeck College London, UK ■ Source references should be inserted in the text in square brackets – [1] – and then listed at the Adam Crowl, Icarus Interstellar, Australia end of the paper. Eric W. Davis, Institute for Advanced Studies at Austin, USA ■ Illustration references should be cited in Kathryn Denning, York University, Toronto, Canada numerical order in the text; those not cited in the Martyn Fogg, Probability Research Group, UK text risk omission. -

PHYSICS of ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3

Chapter 2 PHYSICS OF ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3 1 Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA 2 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA 3 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Toulouse, France This chapter discusses potential technologies for achieving artificial gravity in a space vehicle. We begin with a series of definitions and a general description of the rotational dynamics behind the forces ultimately exerted on the human body during centrifugation, such as gravity level, gravity gradient, and Coriolis force. Human factors considerations and comfort limits associated with a rotating environment are then discussed. Finally, engineering options for designing space vehicles with artificial gravity are presented. Figure 2-01. Artist's concept of one of NASA early (1962) concepts for a manned space station with artificial gravity: a self- inflating 22-m-diameter rotating hexagon. Photo courtesy of NASA. 1 ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY: WHAT IS IT? 1.1 Definition Artificial gravity is defined in this book as the simulation of gravitational forces aboard a space vehicle in free fall (in orbit) or in transit to another planet. Throughout this book, the term artificial gravity is reserved for a spinning spacecraft or a centrifuge within the spacecraft such that a gravity-like force results. One should understand that artificial gravity is not gravity at all. Rather, it is an inertial force that is indistinguishable from normal gravity experience on Earth in terms of its action on any mass. A centrifugal force proportional to the mass that is being accelerated centripetally in a rotating device is experienced rather than a gravitational pull. -

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report NIAC-CP-01-02, USRA Subcontract 07600-091 Narayanan Komerath Sam Wanis, Balakrishnan Ganesh, Joseph Czechowski, Waqar Zaidi, Joshua Hardy, Priya Gopalakrishnan School of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta GA 30332-0150 [email protected] November 2002 Contents 1. Abstract Page 3 2.Introduction to Tailored Force Fields 4 Forces in steady and unsteady potential fields Time line / Application Roadmap 3.Theory connecting acoustic, optical, microwave and radio regimes. 7 4. Task Report: Acoustic Shaping 12 Prior results Inverse-design Shape Generation Software 5. Task Report: Intermediate Term: Architecture for Radiation Shield Project Near Earth 16 Shield-Building Architecture. Launcher and boxcar considerations Deployment of the Outer Grid of the Radiation Shield “Shepherd” Rendezvous-Guidance-Delivery Vehicles. 6. Task Report: Exploration of cost and architecture models for a Space-Based 24 Economy 7. Task Report: Exploration of large-scale construction using Asteroids and Radio 34 Waves Parameter space and design point Power and material requirements Technology status 8. Opportunities& Outreach related to this project 45 SEM Expt. Preparation GAS Expt. Preparation Papers, presentations, discussions Media coverage & public interest “NASA Means Business” program synergy 9. Summary of Issues Identified 49 Metal production and hydrogen recycling Resonator / waveguide technology Cost linkage to comprehensive plan Microwave demonstrator experiment 10. Conclusions 51 11. Acknowledgements 53 12. References 54 2 1. Abstract Before humans can venture to live for extended periods in Space, the problem of building radiation shields must be solved. All current concepts for permanent radiation shields involve very large mass, and expensive and hazardous construction methods. -

California State University, Northridge Low Earth Orbit

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE LOW EARTH ORBIT BUSINESS CENTER A Project submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering by Dallas Gene Bienhoff May 1985 The Proj'ectof Dallas Gene Bienhoff is approved: Dr. B. J. Bluth Professor T1mothy Wm. Fox - Chair California State University, Northridge ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to express my gratitude to those who have helped me over the years to complete this thesis by providing encouragement, prodding and understanding: my advisor, Tim Fox, Chair of Mechanical and Chemical Engineering; Dr. B. J. Bluth for her excellent comments on human factors; Dr. B. J. Campbell for improving the clarity; Richard Swaim, design engineer at Rocketdyne Division of Rockwell International for providing excellent engineering drawings of LEOBC; Mike Morrow, of the Advanced Engineering Department at Rockwell International who provided the Low Earth Orbit Business Center panel figures; Bob Bovill, a commercial artist, who did all the artistic drawings because of his interest in space commercialization; Linda Martin for her word processing skills; my wife, Yolanda, for egging me on without nagging; and finally Erik and Danielle for putting up with the excuse, "I have to v10rk on my paper," for too many years. iv 0 ' PREFACE The Low Earth Orbit Business Center (LEOBC) was initially conceived as a modular structure to be launched aboard the Space Shuttle, it evolved to its present configuration as a result of research, discussions and the desire to increase the efficiency of space utilization. Although the idea of placing space stations into Earth orbit is not new, as is discussed in the first chapter, and the configuration offers nothing new, LEOBC is unique in its application. -

Human Adaptation to Space

Human Adaptation to Space From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Human physiological adaptation to the conditions of space is a challenge faced in the development of human spaceflight. The fundamental engineering problems of escaping Earth's gravity well and developing systems for in space propulsion have been examined for well over a century, and millions of man-hours of research have been spent on them. In recent years there has been an increase in research into the issue of how humans can actually stay in space and will actually survive and work in space for long periods of time. This question requires input from the whole gamut of physical and biological sciences and has now become the greatest challenge, other than funding, to human space exploration. A fundamental step in overcoming this challenge is trying to understand the effects and the impact long space travel has on the human body. Contents [hide] 1 Importance 2 Public perception 3 Effects on humans o 3.1 Unprotected effects 4 Protected effects o 4.1 Gravity receptors o 4.2 Fluids o 4.3 Weight bearing structures o 4.4 Effects of radiation o 4.5 Sense of taste o 4.6 Other physical effects 5 Psychological effects 6 Future prospects 7 See also 8 References 9 Sources Importance Space colonization efforts must take into account the effects of space on the body The sum of mankind's experience has resulted in the accumulation of 58 solar years in space and a much better understanding of how the human body adapts. However, in the future, industrialization of space and exploration of inner and outer planets will require humans to endure longer and longer periods in space. -

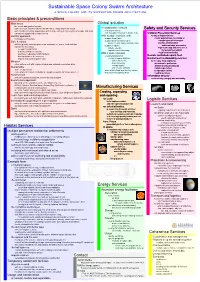

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture A SPACE COLONY AND ITS SUPPORTING SWARM ARCHITECTURE Basic principles & preconditions Main focus Global solution the needs and goals of people sufficient room and the natural habitat that our body and mind needs A collaborative network Safety and Security Services with a sufficiently large population, with a large variety in ages, types of people and skills of a space colony extensively supported on many levels and its supporting swarm architecture Collision Prevention Services Holistic approach With multiple habitats, with for object impact defense, multi-layer architecture support from Earth mostly autonomous, consisting of Safe & robust support from celestial bodies: multiple types of telescopes Moon, Venus, Mars and Asteroids distributed information artificial gravity, radiation protection, atmosphere, water, food and light support in space: and knowledge processing robustness by default: safety, energy, flight vector adjustment services, compartmentalization, logistics, manufacturing by autonomous unit(s) distributed implementation, cloud overblow facility multilayer redundancy with fallback, With a space armada backup facilities & resources at Lagrangian points: Remote controlled repairs fleet impact and collision prevention clouds of space stations, Environment sustainability services with settlements, Mindset for humans, flora and fauna manufacturing, either safe or not, with regular internal and external evacuation drills air and water purification energy supply artificial gravity provisioning -

Ground Into Sky: the Topology of Interstellar

The Avery Review Fred scharmen – Ground into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar was nominated for five Oscars. The Citation: Fred Scharmen, “Ground Into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar,” in The Avery Review, no. 6 movie won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects, many of which were created with (March 2015), http://averyreview.com/issues/6/ analog camera techniques. It has been controversial for its use of emotional ground-into-sky. themes, and its scientific accuracy. The physics in the film is either shockingly sloppy, or accurate enough to generate new peer-reviewed research, depend- ing on which review you read. [1] [2] But the best and most curious thing about [1] Phil Plait, “Interstellar Science: What the movie gets wrong and really wrong about black Interstellar is its topology. holes, relativity, plot, and dialogue,” Slate, http:// Again and again, in different ways, we see the ground lifting up to www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/ space_20/2014/11/interstellar_science_review_ become the sky. The first appearance of this effect is early in the movie—the the_movie_s_black_holes_wormholes_relativity.html, horizon-obliterating dust storms that sweep across the American Midwest. accessed February 24, 2015. Cooper (the main character) and his family are at a baseball game when a dust [2]: Adam Rogers, “Wrinkles in Spacetime: The Warped Astrophysics of Interstellar,” Wired, http:// storm rises, looming like a growing mountain. Drought and blight have killed the www.wired.com/2014/10/astrophysics-interstellar- plant life that binds the soil, the near-future world of the movie has become a black-hole/, accessed February 24, 2015. -

Exploring Artificial Gravity 59

Exploring Artificial gravity 59 Most science fiction stories require some form of artificial gravity to keep spaceship passengers operating in a normal earth-like environment. As it turns out, weightlessness is a very bad condition for astronauts to work in on long-term flights. It causes bones to lose about 1% of their mass every month. A 30 year old traveler to Mars will come back with the bones of a 60 year old! The only known way to create artificial gravity it to supply a force on an astronaut that produces the same acceleration as on the surface of earth: 9.8 meters/sec2 or 32 feet/sec2. This can be done with bungee chords, body restraints or by spinning the spacecraft fast enough to create enough centrifugal acceleration. Centrifugal acceleration is what you feel when your car ‘takes a curve’ and you are shoved sideways into the car door, or what you feel on a roller coaster as it travels a sharp curve in the tracks. Mathematically we can calculate centrifugal acceleration using the formula: V2 A = ------- R Gravitron ride at an amusement park where V is in meters/sec, R is the radius of the turn in meters, and A is the acceleration in meters/sec2. Let’s see how this works for some common situations! Problem 1 - The Gravitron is a popular amusement park ride. The radius of the wall from the center is 7 meters, and at its maximum speed, it rotates at 24 rotations per minute. What is the speed of rotation in meters/sec, and what is the acceleration that you feel? Problem 2 - On a journey to Mars, one design is to have a section of the spacecraft rotate to simulate gravity. -

NEAR of the 21 Lunar Landings, 19—All of the U.S

Copyrights Prof Marko Popovic 2021 NEAR Of the 21 lunar landings, 19—all of the U.S. and Russian landings—occurred between 1966 and 1976. Then humanity took a 37-year break from landing on the moon before China achieved its first lunar touchdown in 2013. Take a look at the first 21 successful lunar landings on this interactive map https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/interactive-map-shows-all-21-successful-moon-landings-180972687/ Moon 1 The near side of the Moon with the major maria (singular mare, vocalized mar-ray) and lunar craters identified. Maria means "seas" in Latin. The maria are basaltic lava plains: i.e., the frozen seas of lava from lava flows. The maria cover ∼ 16% (30%) of the lunar surface (near side). Light areas are Lunar Highlands exhibiting more impact craters than Maria. The far side is pocked by ancient craters, mountains and rugged terrain, largely devoid of the smooth maria we see on the near side. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Moon 2 is a NASA robotic spacecraft currently orbiting the Moon in an eccentric polar mapping orbit. LRO data is essential for planning NASA's future human and robotic missions to the Moon. Launch date: June 18, 2009 Orbital period: 2 hours Orbit height: 31 mi Speed on orbit: 0.9942 miles/s Cost: 504 million USD (2009) The Moon is covered with a gently rolling layer of powdery soil with scattered rocks called the regolith; it is made from debris blasted out of the Lunar craters by the meteor impacts that created them. -

ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY RESEARCH to ENABLE HUMAN SPACE EXPLORATION International Academy of Astronautics

ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY RESEARCH TO ENABLE HUMAN SPACE EXPLORATION International Academy of Astronautics Notice: The cosmic study or position paper that is the subject of this report was approved by the Board of Trustees of the International Academy of Astronautics (IAA). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsoring or funding organizations. For more information about the International Academy of Astronautics, visit the IAA home page at www.iaaweb.org. Copyright 2009 by the International Academy of Astronautics. All rights reserved. The International Academy of Astronautics (IAA), a non governmental organization recognized by the United Nations, was founded in 1960. The purposes of the IAA are to foster the development of astronautics for peaceful purposes, to recognize individuals who have distinguished themselves in areas related to astronautics, and to provide a program through which the membership can contribute to international endeavors and cooperation in the advancement of aerospace activities. © International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) September 2009 Study on ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY RESEARCH TO ENABLE HUMAN SPACE EXPLORATION Edited by Laurence Young, Kazuyoshi Yajima and William Paloski Printing of this Study was sponsored by: DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Cologne, Germany Linder Hoehe D-51147 Cologne, Germany www.dlr.de/me International Academy of Astronautics 6 rue Galilée, BP 1268-16, 75766 Paris Cedex 16, -

Human Spaceflight

Human Spaceflight Space System Design, MAE 342, Princeton University Robert Stengel • Historical concepts and mis-concepts • Manned spacecraft and space stations • Extravehicular activity • Physiological and metabolic issues – Health and space medicine – Radiation exposure – Life support systems • Control capabilities and human error Copyright 2016 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. 1 http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE342.html 1 Impey Barbicane Captain Nicholl 1865 Jules Verne (1828-1905) 2 2 1 Princeton, ‘38 3 3 A Voyage to the Moon Cyrano de Bergerac (1619-1655) • Hercule-Savinien Cyrano de Bergerac • “Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon”, written about 1649, published 1656 or 1657 • English translation, 1687 • In Firestone Library (below & left) 4 4 2 Cyrano's Voyage to the Moon and Back 5 5 1952 Rocket Ship/Space Station Concept C. Ryan, W. von Braun, et al, Across the Space Frontier, Collier’s Magazine Launch weight: 14M lb 6 6 3 Trouble in the Spacecraft: Ejection Capsule 7 7 Why Humans in Space? • Exploration • Scientific discovery • Engineering development • Construction, maintenance, and repair • Pilots, tourists, and tour guides 8 8 4 Man vs. Machine (Handbook of Astronautical Engineering, 1961) 9 9 Performance Issues for Manned Spaceflight • Flexibility, learning, • Physical labor and judgment • Endurance • Information bandwidth, • Ergonomics display, and • Control systems communication • Re-entry systems and • Pre-flight training recovery • Performance variation • Tools and equipment • Extra-vehicular activity • Recycling • Physical labor 10 10 5 Cooper-Harper Pilot Opinion Rating (NASA TN D-5153, 1969) 11 11 Cooper-Harper Pilot Opinion Rating (NASA TN D-5153, 1969) 12 12 6 Human Space Experience to April 2016 § Continuous human space presence since Oct.