Hadrian's Turf Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Art History THE HADRIANIC TONDI ON THE ARCH OF CONSTANTINE: NEW PERSPECTIVES ON THE EASTERN PARADIGMS A Dissertation in Art History by Gerald A. Hess © 2011 Gerald A. Hess Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 The dissertation of Gerald A. Hess was reviewed and approved* by the following: Elizabeth Walters Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Associate Professor of Art History Brian Curran Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head, Department of Art History Donald Redford Professor of Classics and Mediterranean Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation is a study of the impact of eastern traditions, culture, and individuals on the Hadrianic tondi. The tondi were originally commissioned by the emperor Hadrian in the second century for an unknown monument and then later reused by Constantine for his fourth century arch in Rome. Many scholars have investigated the tondi, which among the eight roundels depict scenes of hunting and sacrifice. However, previous Hadrianic scholarship has been limited to addressing the tondi in a general way without fully considering their patron‘s personal history and deep seated motivations for wanting a monument with form and content akin to the prerogatives of eastern rulers and oriental princes. In this dissertation, I have studied Hadrian as an individual imbued with wisdom about the cultural and ruling traditions of both Rome and the many nations that made up the vast Roman realm of the second century. -

Routes4u Feasibility Study on the Roman Heritage Route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region

Routes4U Project Feasibility Study on the Roman Heritage Route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region Routes4U Feasibility Study on the Roman Heritage Route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region Routes4U Project Routes4U Feasibility study on the Roman Heritage route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region ROUTES4U FEASIBILITY STUDY ON THE ROMAN HERITAGE ROUTE IN THE ADRIATIC AND IONIAN REGION February 2019 The present study has been developed in the framework of Routes4U, the Joint Programme between the Council of Europe and the European Commission (DG REGIO). Routes4U aims to foster regional development through the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe programme in the four EU macro-regions: the Adriatic and Ionian, Alpine, Baltic Sea and Danube Regions. A special thank you goes to the author Vlasta Klarić, and to the numerous partners and stakeholders who supported the study. The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. www.coe.int/routes4u 2 / 107 Routes4U Feasibility study on the Roman Heritage route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 5 I. STATE-OF-THE-ART ANALYSIS OF ROMAN HERITAGE IN THE AIR ........................... 7 1. Geographical distribution ................................................................................................................................... -

AW Nr5 Okt2010.Indd 48 03-10-2010 08:30:52 the Debate

THE DEBATE The fate of the Ninth The curious disappearance of Legio VIIII Hispana © ajbdesign.com Andrew Brozyna, IN 1954, ROSEMARY SUTCLIFF PUBLISHED A NOVEL ABOUT ROMAN BRITAIN. The last testimony of the presence of IT CAUGHT THE IMAGINATION OF AN ENTIRE GENERATION OF READERS WITH the Ninth Legion in Britain. Dated to AD 108, it testifies to a building project ITS TALE OF THE NINTH LEGION, DESTROYED IN THE MISTS OF SCOTLAND. A undertaken by the legion. BBC DRAMATISATION CAPTIVATED A FRESH GENERATION IN 1977. AND NOW A NEW MOTION PICTURE IS SET TO REVIVE INTEREST IN THE faTE OF THE LOST LEGION. BUT WAS IT REALLY DESTROYED IN BRITAIN DURING THE REIGN OF It was clearly a military building inscrip- tion, dating from the time when Roman HADRIAN? OR HAVE WE faLLEN FOR A MYTH THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN LAID builders were gradually refurbishing TO REST FIFTY YEARS AGO? the early turf-and-timber forts and fortresses in Britain, and reconstructing their defences in stone. The find-spot By Duncan B Campbell survived, however, for scholars of the was close to the original location of day to reconstruct the original text: the south-east gate into the legionary On the morning of 7 October 1854, The fortress of Eburacum. So the inscription York Herald and General Advertiser “The Emperor Caesar Nerva Trajan probably celebrated the construction of carried a short report, tucked away in the Augustus, son of the deified Nerva, the gateway, built by the emperor per bottom corner of an inside page. Under Conqueror of Germany, Conqueror legionem VIIII Hispanam (“through the the headline “Antiquarian Discovery of Dacia, Chief Priest, in his twelfth agency of the Ninth Hispana Legion”). -

THE FOUNDATION of ROMAN CAPITOLIAS a Hypothesis

ARAM, 23 (2011) 35-62. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.23.0.2959651 THE FOUNDATION OF ROMAN CAPITOLIAS A Hypothesis Mr. JULIAN M.C. BOWSHER1 (Museum of London Archaeology) INTRODUCTION The town of Beit Ras in northern Jordan is the site of the ancient city of Capitolias. The identification and geographical location of Capitolias was deter- mined in the 19th century. According to numismatic data, the city was “founded” in 97/98 AD. However, it remains an enigma since no one appears to have addressed the questions of why and when Capitolias, as a Roman city, came into being. This paper will concentrate on the Roman city of Capitolias, re-examining the known sources as well as analysing the broader geographic, economic, political, military, and religious elements. These factors will be brought together to produce a hypothesis covering the why and when. This introduction will begin with a review of early accounts of the site and the history of its identifica- tion with Capitolias, before examining its foundation. Historiography The first known (western) description of the site of Beit Ras was by Ulrich Jasper Seetzen who was there in the spring of 1806. He noted that “… from some ancient remains of architecture [it] appears to have been once a consider- able town.” but he was unable to identify it.2 J.L. Burckhardt travelled in the area in 1812 and although he did not manage to visit the site, he was told that at Beit er Ras the “ruins were of large extent, that there were no columns standing, but that large ones were lying upon the ground”. -

Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Winter 2014

Northern Michigan University Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Winter 2014 Course ID Dept Code Credits A B C D F I MG S U W Total Unsatisfactory % Unsatisfactory ELI 083B LG 3 1 1 1 100.0% MU 112 MU 0.5 1 2 3 2 66.7% PT 162 TOS 4 2 2 1 5 1 11 7 63.6% ATR 110 PE 1 3 5 5 4 9 3 29 16 55.2% MA 100 MA 4 14 22 25 24 15 26 126 65 51.6% UN 110 EN 2 4 4 2 5 1 2 2 20 10 50.0% ELI 063A LG 3 1 1 2 1 50.0% EN 101 EN 2 2 4 5 4 3 2 20 9 45.0% ET 113 ENGT 4 2 6 3 5 4 20 9 45.0% COS 123 TOS 8 3 3 9 7 5 27 12 44.4% MA 106 MA 3 3 7 5 5 4 3 27 12 44.4% EN 090 EN 4 3 7 1 4 4 19 8 42.1% EN 090W EN 1 3 7 1 4 4 19 8 42.1% CH 112A CH 5 15 27 19 19 14 8 102 41 40.2% LPM 101 CJ 4 10 5 2 6 5 28 11 39.3% MA 090 MA 4 5 10 15 4 4 1 10 49 19 38.8% PY 100S PY 4 26 38 29 23 10 25 151 58 38.4% IM 105 TOS 4 4 9 8 3 9 1 34 13 38.2% PS 105 PS 4 17 30 33 17 19 12 128 48 37.5% FR 102 LG 4 15 5 2 3 1 9 35 13 37.1% GC 100 GC 4 18 45 53 38 8 1 17 180 64 35.6% CS 120 MA 4 28 17 20 5 18 4 8 100 35 35.0% MF 133 ENGT 2 7 6 1 3 3 20 7 35.0% DD 100 ENGT 4 2 14 3 2 2 6 29 10 34.5% HS 102 HS 4 12 17 17 5 10 9 70 24 34.3% AD 111 AD 4 5 9 1 3 3 21 7 33.3% GR 102 LG 4 5 3 4 1 2 3 18 6 33.3% OIS 161 BUS 4 5 4 3 1 2 3 18 6 33.3% MU 104 MU 2 2 4 4 2 3 15 5 33.3% ELI 073A LG 3 2 1 3 1 33.3% CH 111 CH 5 22 42 34 16 14 16 144 46 31.9% CH 109 CH 4 17 20 15 2 1 1 18 74 22 29.7% AD 119 AD 4 1 7 4 1 1 3 17 5 29.4% BI 100 BI 4 7 18 17 5 8 1 3 59 17 28.8% BI 111 BI 4 41 58 26 9 21 20 175 50 28.6% PS 101 PS 4 30 32 37 5 18 15 137 38 27.7% AD 134 AD 4 5 20 9 2 5 6 47 13 27.7% PH 102 PH 3 1 -

A Comparative Study of Roman-Period Leather from Northern Britain. Mphil(R) Thesis

n Douglas, Charlotte R. (2015) A comparative study of Roman-period leather from northern Britain. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7384/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Comparative Study of Roman-period Leather from Northern Britain Charlotte R. Douglas MA Submitted in fulfilment for the requirements of the Degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow December 2015 © Charlotte R. Douglas 2015 Abstract This thesis draws together all of the data on Roman-period leather from northern Britain and conducts a cohesive assessment of past research, current questions and future possibilities. The study area comprises Roman sites on or immediately to the south of Hadrian’s Wall and all sites to the north. Leather has been recovered from 52 Roman sites, totalling at least 14,215 finds comprising manufactured goods, waste leather from leatherworking and miscellaneous/unidentifiable material. This thesis explores how leather and leather goods were resourced, processed, manufactured and supplied across northern Britain. -

Deir El-Bahari

Supplement IV Supplement P J J T APYROLOGY URISTIC OF OURNAL HE DEIR EL-BAHARI IN THE HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN PERIODS JJP Supplement VI T HE J OURNAL OF J URISTIC P APYROLOGY Supplement IV WARSAW 2005 ADAM ¸AJTAR BASED ONGREEKSOURCES OFANEGYPTIANTEMPLE A STUDY IN THE D AND EIR EL- R OMAN H ELLENISTIC B P AHARI ERIODS DEIR EL-BAHARI IN THE HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN PERIODS APYROLOGY P URISTIC J OF AL OURN J HE T Supplement IV WARSAW UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF PAPYROLOGY THE RAPHAEL TAUBENSCHLAG FOUNDATION THE JOURNAL OF JURISTIC PAPYROLOGY Supplements SERIES EDITORS TOMASZ DERDA JAKUB URBANIK VOLUME IV DEIR EL-BAHARI IN THE HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN PERIODS APYROLOGY A STUDY OF AN EGYPTIAN TEMPLE P BASED ON GREEK SOURCES ADAM ¸AJTAR URISTIC J OF AL OURN J HE Supplement IV T WARSAW 2005 rz04 1/9/06 4:30 PM Page 1 Supplements to The Journal of Juristic Papyrology are jointly published by Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University and Fundacja im. Rafała Taubenschlaga, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00–927 Warszawa64 tel. (+48.22) 55.20.388 and (+48.22) 55.20.384, fax: (+48.22) 55.24.319 e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] web-page: <http://www.papyrology.uw.edu.pl> Cover design by Maryna Wiśniewska Computer design and DTP by Tomasz Derda and Paweł Marcisz © by Adam Łajtar and Fundacja im. Rafała Taubenschlaga Warszawa 2006 This publication has been published with financial support from the Rector of Warsaw University, Institute of Archaeology of Warsaw University and Warsaw University Centre for Mediterranean Archaeology in Cairo ISBN 83–918250–3–5 Wydanie I. -

Sunday in Roman Paganism

Sunday Sacredness In Roman Paganism A history of the planetary week and its “day of the Sun” in the paganism of the Roman world during the early centuries of the Christian Era By ROBERT LEO ODOM MINISTERIAL READING COURSE SELECTION FOR 1944 MINISTERIAL ASSOCIATION OF SEVENTH DAY ADVENTISTS REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION TAKOMA PARK, WASHINGTON, D. C. The Contents 1. The Pagan Planetary Week 2. Is the Planetary Week of Babylonian Origin? 3. The Planetary Week in Mesopotamia 4. The Diffusion of Chaldean Astrology 5. The Planetary Week in Rome 6. The Planetary Week in the First Century BC 7. The Planetary Week in the First Century AD 8. The Planetary Week in the Second Century AD 9. The Planetary Week in the Third Century AD 10. “The Sun, the Lord of the Roman Empire 11. “On the Lord’s Day of the Sun 12. The Sunday of Sun Worship 13. The First Civil Sunday Laws 14. Sylvester and the Days of the Week 15. The Planetary Week in the Philocalian Almanac 16. The Power Behind the Planetary Week 17. Doctor James Kennedy's Sermon Appendix -The Teutonic Pagan Week Bibliography References Internet Resources THE WEEK 1 THE Sun still rules the week’s initial day, The Moon o’er Monday yet retains the sway; But Tuesday, which to Mars was whilom given, Is Tuesco’s subject in the northern heaven; And Wotlen hath the charge of Wednesday, Which did belong of old to Mercury. And Jove himself surrenders his own day To Thor, a barbarous god of Saxon day. -

Presidential Address 2015. Coin Hoards

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS 2015 COIN HOARDS AND HOARDING (4): THE DENARIUS PERIOD, AD 69−238 ROGER BLAND Introduction THE subject of this paper is the hoards of the denarius period, from the Flavian period in AD 69 through to the replacement of the denarius by the radiate in AD 238. This study is part of the AHRC-funded project ‘Crisis or continuity? Hoards and hoarding in Iron Age and Roman Britain’, in the course of which Eleanor Ghey has compiled a summary of 3,340 coin hoards from Britain.1 Fig. 1 shows the numbers of coin hoards per annum from the Iron Age and Roman periods according to the date of the latest coin – which of course is not necessarily the same as the date of burial, although I argue below that at this period, when there was a regular supply of new coin entering the province, the date of deposition is likely to be close to the date of the latest coin. 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 –120 –95 –70 –45 –20 6315681 106 131 156 181 206 231 256 281 306 331 356 381 406 Fig. 1. Coin hoards per annum, c.120 BC–AD 410 Acknowledgements My thanks to the Coin Hoards project team, especially Eleanor Ghey for all her work on the database, without which this paper would not have been possible, and also for her comments on a draft of the paper, and to Katherine Robbins for her excellent maps, which are an integral part of this article. I am also grateful to Andrew Burnett and Sam Moorhead for their comments on a draft, to David Mattingly for permission to reproduce Figs 10b, 12b and 15b, and to Chris Howgego for Fig. -

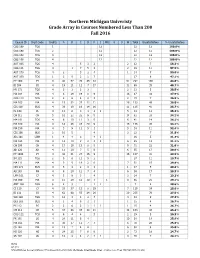

Northern Michigan Univeristy Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Fall 2016

Northern Michigan Univeristy Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Fall 2016 Course ID Dept Code Credits A B C D F I MG S U W Total Unsatisfactory % Unsatisfactory COS 198 TOS 1 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 2 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 3 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 4 12 12 12 100.0% AUT 105 TOS 4 5 3 2 2 12 7 58.3% COS 111 TOS 4 1 7 5 4 2 19 11 57.9% AUT 170 TOS 4 2 5 2 4 1 14 7 50.0% AUT 100 TOS 1 2 5 2 1 7 17 8 47.1% PY 100L PY 4 40 57 70 45 33 52 297 130 43.8% BI 104 BI 4 19 21 11 7 17 11 86 35 40.7% HV 172 TOS 4 3 3 2 3 2 13 5 38.5% MA 104 MA 4 6 29 19 8 9 16 87 33 37.9% COS 113 TOS 8 2 6 4 2 3 2 19 7 36.8% MA 103 MA 4 15 32 37 12 11 26 133 49 36.8% CIS 110 BUS 4 39 19 16 14 16 11 115 41 35.7% PL 160 PL 4 11 8 3 4 2 1 5 34 12 35.3% CH 112 CH 5 10 22 22 9 5 14 82 28 34.1% HM 101 TOS 4 6 10 11 3 5 6 41 14 34.1% MA 100 MA 4 18 36 37 20 9 16 136 45 33.1% MA 150 MA 4 3 9 11 5 1 5 34 11 32.4% CIS 100 BUS 2 10 5 4 3 22 7 31.8% AIS 101 LIBR 1 4 4 3 4 1 16 5 31.3% MA 163 MA 4 14 10 8 2 3 3 6 45 14 31.1% CH 109 CH 4 17 19 13 8 5 9 71 22 31.0% AD 120 AD 4 11 20 7 5 6 6 55 17 30.9% PY 100S PY 4 38 31 27 16 9 16 137 41 29.9% IM 115 TOS 2 9 6 11 9 2 37 11 29.7% MA 111 MA 4 9 9 18 2 6 7 51 15 29.4% OIS 171 BUS 4 6 4 2 3 1 1 17 5 29.4% AS 103 PH 4 9 20 12 7 4 6 58 17 29.3% LPM 101 CJ 4 5 9 3 4 3 24 7 29.2% MA 090 MA 4 15 29 16 10 7 1 8 86 25 29.1% AMT 102 TOS 6 2 3 1 1 7 2 28.6% CJ 110 CJ 4 35 37 13 8 19 7 119 34 28.6% BI 111 BI 4 62 68 55 24 26 20 255 70 27.5% WD 180 TOS 4 18 3 3 2 4 3 33 9 27.3% OIS 183 BUS 4 1 4 6 2 1 1 15 4 26.7% PS 112 -

NYU Abu Dhabi Bulletin 2014-2015

NYU ABU DHABI BULLETIN 2014–15 2 2014–15 | DEPARTMENT | MAJOR NEW YORK UNIVERSITY ABU DHABI BULLETIN 2014–15 Please note that this pdf was last edited on September 9, 2014, this subsequent to the printed edition. NYU Abu Dhabi Saadiyat Campus PO Box 129188 Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates The policies, requirements, course offerings, and other information set forth in this bulletin are subject to change without notice and at the discretion of the administration. For the most current information, please see nyuad.nyu.edu. INTRODUCTION 340 Graduation Honors 340 Incompletes 4 Welcome from Vice Chancellor 340 Integrity Commitment Alfred H. Bloom 340 Leave of Absence 6 Educating Global Leaders 341 Midterm Assessment 8 About Abu Dhabi: A New World City 341 Minimum Grades 9 Pathway to the Professions 341 Pass/Fail 342 Religious Holidays BASIC INFORMATION 342 Repeating Courses 342 Transcripts 12 Programs at a Glance 343 Transfer Credit 14 Academic Calendar 343 Withdrawal from a Course 16 Language of Instruction 16 Accreditation STUDENT AFFAIRS AND CAMPUS LIFE 16 Degrees and Graduation Requirements 19 Admissions 345 Advisement and Mentoring 345 Office of First-Year Programming COURSES OF INSTRUCTION 346 Career Services, Internships, Global Awards, and Pre-Professional Advising 22 The Core Curriculum 346 Office of Community Outreach 58 Arts and Humanities 347 Fitness, Sports and Recreation 140 Social Science 348 Health and Wellness Services 180 Science and Mathematics 348 Student Activities 228 Engineering 349 Religious Life 254 Multidisciplinary -

The Marble Hall of Furius Aptus: Phrygian Marble in Rome and Ephesus Alfred Hirt

The Marble Hall of Furius Aptus: Phrygian Marble in Rome and Ephesus Alfred Hirt To cite this version: Alfred Hirt. The Marble Hall of Furius Aptus: Phrygian Marble in Rome and Ephesus. Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz, De Boccard, 2017, 28, pp.231-248. halshs-01907274 HAL Id: halshs-01907274 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01907274 Submitted on 29 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CAHIERS DU CENTRE GUSTAVE-GLOTZ Les Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz sont nés XXVIII - 2017 en 1990, sous la forme d’un recueil d’articles 2017 C A H I E R S intitulé « Du pouvoir dans l’Antiquité » et coordonné par Claude Nicolet. Ils se sont Violaine Sebillotte Cuchet, Gender studies et domination masculine. Les citoyennes DU CENTRE GUSTAVE transformés en une revue annuelle dès l’année de l’Athènes classique, un défi pour l’historien des institutions ...................................... 7 suivante. Depuis la fusion entre le Centre Francesco Verrico, Le commissioni di redazione dei senatoconsulti (qui scribundo ) : i segni della crisi e le riforme di Augusto ....................................................... 31 Gustave Glotz, le Centre Louis Gernet et adfuerunt XXVIII- Anthony Àlvarez Melero, Matronae stolatae : titulature officielle ou prédicat hono- l’équipe Phéacie en 2010, ils constituent rifique ? .......................................................................................................................................