2017 Human Rights in Bulgaria In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

Nicopolis Ad Nestum and Its Place in the Ancient Road Infrastructure of Southwestern Thracia

BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE, XLIV, 2018 Proceedings of the First International Roman and Late Antique Thrace Conference “Cities, Territories and Identities” (Plovdiv, 3rd – 7th October 2016) Nicopolis ad Nestum and Its Place in the Ancient Road Infrastructure of Southwestern Thracia Svetla PETROVA Abstract: The road network of main and secondary roads for Nicopolis ad Nestum has not been studied comprehensively so far. Our research was carried out in the pe- riod 2010-2015. We have gathered the preserved parts of roads with bridges, together with the results of archaeological studies and data about the settlements alongside these roads. The Roman city of Nicopolis ad Nestum inherited road connections from 1 One of the first descriptions of the pre-Roman times, which were further developed. Road construction in the area has road net in the area of Nevrokop belongs been traced chronologically from the pre-Roman roads to the Roman primary and to Captain A. Benderev (Бендерев 1890, secondary ones for the ancient city. There were several newly built roadbeds that were 461-470). V. Kanchov is the next to follow important for the area and connected Nicopolis with Via Diagonalis and Via Egnatia. the ancient road across the Rhodopes, The elements of infrastructure have been established: primary and secondary roads, connecting Nicopolis ad Nestum with crossings, facilities and roadside stations. Also the locations of custom-houses have the valley of the Hebros river (Кънчов been found at the border between Parthicopolis and Nicopolis ad Nestum. We have 1894, 235-247). The road from the identified a dense network of road infrastructure with relatively straight sections and a Nestos river (at Nicopolis) to Dospat, lot of local roads and bridges, connecting the settlements in the territory of Nicopolis the so-called Trans-Rhodopean road, ad Nestum. -

Bulgaria Page 1 of 14

2005 Country Report on Human Rights in Bulgaria Page 1 of 14 Facing the Threat Posed by Iranian Regime | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Bulgaria Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy of approximately 7.7 million persons, and is ruled by a coalition government headed by Prime Minister Sergei Stanishev. Multiparty parliamentary elections in June were deemed generally free and fair despite some reported irregularities. While civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of law enforcement officers, there were some instances in which law enforcement officers acted independently of government authority. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, there were problems in several areas. The following human rights problems were reported: police abuses, including beatings and mistreatment, of criminal suspects, prison inmates, and members of minorities harsh conditions in prisons and detention facilities arbitrary arrest and detention impunity limitations on freedom of the press some restrictions on freedom of religion discrimination against certain religious minorities widespread corruption in executive and judicial branches violence and discrimination against women, children, and minority groups, particularly the Roma trafficking in persons discrimination against persons with disabilities child labor RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life Neither the government nor its agents committed any politically motivated killings; however, there were reports that police killed two persons during the year. On November 10, Anguel Dimitrov died while being arrested in a nationwide operation against organized crime. -

Implementation of the Structural Funds in Bulgaria Monthly Brief 15 August

Implementation of the Structural funds in Bulgaria Monthly brief 15 August-30 September, 2010 Horizontal issues and legislative procedures A draft Council of Ministers Decree amending CoM Decree 121/2007 has been prepared by the Central Coordination Unit and is to be sent for interministerial coordination procedure. The proposed amendments aim at merging the administrative compliance and eligibility compliance checks in the evaluation process of the project proposals. A shorter and more efficient evaluation process is thus to be achieved. In September, 2010, the Council of Ministers adopted the Decree, which set up a new position “assistant on management of European projects and programs”. The aim of the decree is to assist the MAs/IBs needs of specific expertise and knowledge in order to improve the conditions for the successful implementation of EU programs and projects. The assignment of the experts will be financed from the technical assistance of the OPs. The positions will be occupied until the completion of the programs. The national methodology on financial corrections is under revision in order to be prepared amendments, based on the adopted new Public Procurement Law (PPL). The methodology set up the main principles, criteria and indicative scales for determining financial corrections to be made to expenditure co-financed by the Structural Funds or Cohesion Fund for non-compliance with the rules on public procurement legislation. Two meetings of the Horizontal Network of experts for evaluation of the National Strategic Reference Framework and Operational Programmes were held respectively on 03 August and 30 September 2010. Participants in the meeting by the EC, MAs and CCU discussed the progress of the evaluation plans of the NSRF and OPs, reported during the previous meeting of the Network as well as the information about the upcoming meeting of the DG REGIO Evaluation Network that will take place on October 14-15, 2010. -

Open Society Institute Sofia

Open Society Institute - Sofia 2015 Annual Report OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE SOFIA 2015 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Mission 3 1 Report of the Executive Director 5 2 Financial Profile 6 NGO Programme in Bulgaria under the EEA Financial Mechanism 2009- 3 11 2014 4 European Policies Programme 23 Governance and Public Policies Programme 26 5 Project Generation Facility - 29 Making the Most of European Union Structural Funds for Roma Inclusion 6 Legal Programme 31 7 Public Debate Programme 33 8 Emergency Fund of the Open Society Institute 34 Roma Programme 35 9 Scholarship Programme for doctors and post-graduate medicine students 36 of Roma origin Traineeship Programme at the US Embassy “Bridging Roma and Career 36 Opportunities” with the financial support of the US Embassy 10 Project Design Unit 37 2 MISSION To develop and support the values and practices of the open society in Bulgaria - To support the democratization of the public life - To work for the extension and guaranteeing of civil freedoms - To support the strengthening of civil sector institutions - To support the European integration and regional cooperation of Bulgaria 3 Founder George Soros Board of Trustees Pepka Boyadzhieva, Chair Ivan Bedrov Lachezar Bogdanov Milena Stefanova Petya Kabakchieva Aleksandar Kashamov Executive Director Georgi Stoychev Financial Director Veliko Sherbanov Programme Directors Boyan Zahariev Valentina Kazanska Ivanka Ivanova Dimitar Dimitrov Marin Lesinsky Elitsa Markova Anita Baykusheva Senior Economist Georgi Angelov Sociological Analyses Unit Aleksey Pamporov Dragomira Belcheva Petya Braynova Project Design Unit Elitsa Markova Teodora Ivanova 4 1. REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR In 2015, the Open Society Institute – Sofia continued working on four main priorities: good governance, rule of law and human rights, European policies and civic participation. -

2018 Bulgaria

MONITORING OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS’ RECOMMENDATION CM/REC (2010)5 ON MEASURES TO COMBAT DISCRIMINATION ON GROUNDS OF SEXUAL ORIENTATION OR GENDER IDENTITY REPORT ON THE REPUBLIC BULGARIA WRITTEN BY: DENITSA LYUBENOVA - ATTORNEY-AT-LAW DENIZA GEORGIEVA Report on the Republic of Bulgaria Background Information 1 Executive Summary 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 5 Purpose of the Report 10 Political System and Demographics 11 Methodology 11 1. Right to life, security and protection from violence 15 “Hate crimes” and other hate-motivated incidents 15 Hate speech 19 2. Freedom of association 19 3. Freedom of expression and peaceful assembly 20 4. Right to respect for private and family life 21 Right to respect for private and family life of same-sex families 21 Right to respect for private and family life of trans and intersex people 28 5. Employment 29 6. Education 31 7. Health 34 8. Housing 38 9. Sports 39 10. Right to seek asylum 40 11. National Human Rights Structures 42 12. Discrimination on multiple grounds 43 Report on the Republic of Bulgaria Background Information In 2010 the Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe adopted the Recommendation on measures to combat discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity1, recognizing that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons have been for centuries exposed and are still subjected to homophobia, transphobia and other forms of discrimination and social exclusion. This significant document aims to recall that human rights are universal and should guarantee the equal dignity of all human beings and the enjoyment of rights and freedoms of all individuals without discrimination on any ground, including sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics. -

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Bulgaria | Freedom House Page 1 of 17 BulgariaFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 80 FREE /100 Political Rights 34 Civil Liberties 46 80 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. TOP Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/bulgaria/freedom-world/2020 7/24/2020 Bulgaria | Freedom House Page 2 of 17 Bulgaria’s democratic system holds competitive elections and has seen several transfers of power in recent decades. The country continues to struggle with political corruption and organized crime. The media sector is less pluralistic, as ownership concentration has considerably increased in the last 10 years. Journalists encounter threats and even violence in the course of their work and are sometimes fired for not following the editorial line. Ethnic minorities, particularly Roma, face discrimination. Despite funding shortages and other obstacles, civil society groups have been active and influential. Key Developments in 2019 • In December, the parliament reinstituted the state subsidies for political parties, which had controversially been cut in July. The July amendment to the Political Parties Act also lifted the ceiling on donations for political parties by private persons, businesses, and other organizations. • In September, the director general of the Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) removed a prominent journalist from a live-broadcast and suspended BNR programming for an unprecedented five hours. Civil society’s strong reaction prompted the formation of a parliamentary committee to investigate the events. BNR’s director was ousted in October. • In September, an outcry from right-wing political groups claimed the judiciary’s independence was threatened, after an Australian national, convicted of killing a law student in 2007, was granted parole. -

Network Program Democracy

Democracy Network Program DemNet II: Building Civil Society in Bulgaria Final Report Democracy Network Program DemNet II: Building Civil Society in Bulgaria 1998-2002 FINAL REPORT TO THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Cooperative Agreement No. 181-A-00-98-00320-00 Institute for Sustainable Communities 535 Stone Cutters Way, Montpelier, VT 05602 USA Phone 802-229-2900 | Fax 802-229-2919 [email protected] | www.iscvt.org April 2003 Photos, front and back inside covers: Bulgarian landscapes; next page: DemNet-supported activities of SO partners and NGOs working for positive change in Bulgaria. Table of Contents I. Executive Summary • 6 II. The Context • 8 III. Program Design & Goals • 9 IV. Strengthening the Capacity of SO Partners • 11 • SELECTING SUPPORT ORGANIZATION PARTNERS • ORGANIZATIONAL STRENGTHENING • DEEPENING PROGRAM IMPACT • KEY OUTCOMES IN DEMNET’S FUNCTIONAL AREAS V. SO Partner Performance Stories • 22 VI. Supporting a Vibrant NGO Sector & Strengthening Civil Society in Bulgaria • 24 • TARGETING UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS & IMPROVING SOCIAL SAFETY NETS • CREATING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY • NETWORKING & COALITION BUILDING FOR SUPPORT & SUSTAINABILITY • STRENGTHENING OUTREACH & PUBLIC RELATIONS • INCREASING CITIZEN PARTICIPATION IN POLICY DIALOGUE VII. Lessons Learned • 27 VIII. Conclusion • 29 IX. Attachments A: DEMNET SO PARTNER PUBLICATION B: SO PARTNER SUMMARIES C: ORGANIZATIONAL STRENGTHENING & PERFORMANCE MONITORING COMPONENTS D: SERVICE QUALITY REVIEW REPORT E: DONOR SURVEY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY F: ENGAGE INITIATIVE REPORT G: TRAVEL NOTES PUBLICATION (ENGAGE INITIATIVE) H: VOICES FOR CHANGE PUBLICATION I: ADVOCACY INITIATIVE REPORT J: LEADING LIGHTS PUBLICATION K: SUMMARY OF NGO GRANTEES L: SENSE OF EMPOWERMENT VIDEO Acknowledgements The success of any project is in the hands of many people—the SO partners, the capable and dedicated ISC staff in Bulgaria, many excellent consultants who supported the program, and the Bulgaria USAID mission that provided sound support and counsel at critical junctures. -

Appendix 1 D Municipalities and Mountainous

National Agriculture and Rural Development Plan 2000-2006 APPENDIX 1 D MUNICIPALITIES AND MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS WITH POTENTIAL FOR RURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT MUNICIPALITIES MOUNTAINOUS SETTLEMENTS Municipality Settlements* Izgrev, Belo pole, Bistrica, , Buchino, Bylgarchevo, Gabrovo, Gorno Bansko(1), Belitza, Gotze Delchev, Garmen, Kresna, Hyrsovo, Debochica, Delvino, Drenkovo, Dybrava, Elenovo, Klisura, BLAGOEVGRAD Petrich(1), Razlog, Sandanski(1), Satovcha, Simitly, Blagoevgrad Leshko, Lisiia, Marulevo, Moshtanec, Obel, Padesh, Rilci, Selishte, Strumiani, Hadjidimovo, Jacoruda. Logodaj, Cerovo Sungurlare, Sredets, Malko Tarnovo, Tzarevo (4), BOURGAS Primorsko(1), Sozopol(1), Pomorie(1), Nesebar(1), Aitos, Kamenovo, Karnobat, Ruen. Aksakovo, Avren, Biala, Dolni Chiflik, Dalgopol, VARNA Valchi Dol, Beloslav, Suvorovo, Provadia, Vetrino. Belchevci, Boichovci, Voneshta voda, Vyglevci, Goranovci, Doinovci, VELIKO Elena, Zlataritsa, Liaskovets, Pavlikeni, Polski Veliko Dolni Damianovci, Ivanovci, Iovchevci, Kladni dial, Klyshka reka, Lagerite, TARNOVO Trambesh, Strajitsa, Suhindol. Tarnovo Mishemorkov han, Nikiup, Piramidata, Prodanovci, Radkovci, Raikovci, Samsiite, Seimenite, Semkovci, Terziite, Todorovci, Ceperanite, Conkovci Belogradchik, Kula, Chuprene, Boinitsa, Bregovo, VIDIN Gramada, Dimovo, Makresh, Novo Selo, Rujintsi. Mezdra, Krivodol, Borovan, Biala Slatina, Oriahovo, VRATZA Vratza Zgorigrad, Liutadjik, Pavolche, Chelopek Roman, Hairedin. Angelov, Balanite, Bankovci, Bekriite, Bogdanchovci, Bojencite, Boinovci, Boicheta, -

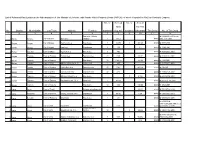

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Bulgaria SIGI 2019 Category Low SIGI Value 2019 23%

Country Bulgaria SIGI 2019 Category Low SIGI Value 2019 23% Discrimination in the family 27% Legal framework on child marriage 50% Percentage of girls under 18 married 1% Legal framework on household responsibilities 50% Proportion of the population declaring that children will suffer if mothers are working outside home for a pay 56% Female to male ratio of time spent on unpaid care work 2.0 Legal framework on inheritance 0% Legal framework on divorce 25% Restricted physical integrity 16% Legal framework on violence against women 75% Proportion of the female population justifying domestic violence 18% Prevalence of domestic violence against women (lifetime) 23% Sex ratio at birth (natural =105) 105.8 Legal framework on reproductive rights 0% Female population with unmet needs for family planning 14% Restricted access to productive and financial resources 30% Legal framework on working rights 100% Proportion of the population declaring this is not acceptable for a woman in their family to work outside home for a pay 6% Share of managers (male) 61% Legal framework on access to non-land assets 25% Share of house owners (male) - Legal framework on access to land assets 25% Share of agricultural land holders (male) 77% Legal framework on access to financial services 25% Share of account holders (male) 48% Restricted civil liberties 20% Legal framework on civil rights 0% Legal framework on freedom of movement 0% Percentage of women in the total number of persons not feeling safe walking alone at night 64% Legal framework on political participation 50% Share of the population that believes men are better political leaders than women 44% Percentage of male MP’s 76% Legal framework on access to justice 0% Share of women declaring lack of confidence in the justice system 56% Note: Higher values indicate higher inequality.