Episodic Memory and Common Sense: How Far Apart?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

The Unconscious Mind: Kinder and Gentler Than That

3/20/2013 The Freudian 20th Century “Freud in 21st-Century America” The Unconscious Mind: Kinder and Gentler Than That John F. Kihlstrom Forbidden Planet (1956) Department of Psychology University of California, Berkeley 1 2 The Discovery of the Unconscious Petites Perceptions Ellenberger (1970) Leibniz (1704/1981); Ellenberger (1970) • At every moment there is in us an infinity of perceptions, unaccompanied by awareness or reflection…. That is why we are never indifferent, even when we appear to be most so…. The choice that we make arises from these insensible stimuli, which… make us find one direction of movement more comfortable than the 3 other. 4 The Limen Unconscious Inferences Herbart (1819) Helmholtz (1866/1968) • One of the older ideas can… be • The psychic activities that lead us to infer that completely driven out of consciousness by there in front of us at a certain place there is a a new much weaker idea. On the other certain object of a certain character, are generally hand its pressure there is not to be not conscious activities, but unconscious ones. In regarded as without effect; rather it works their result they are the equivalent to conclusion…. with full power against the ideas which are But what seems to differentiate them from a conclusion, in the ordinary sense of that word, is present in consciousness. It thus causes that a conclusion is an act of conscious thought…. a particular state of consciousness, though Still it may be permissible to speak of the psychic its object is in no sense really imagined. acts of ordinary perception as unconscious 5 conclusions…. -

Implicit and Explicit Knowledge About Language

Comp. by: TPrasath Date:27/12/06 Time:22:59:29 Stage:First Proof File Path:// spiina1001z/womat/production/PRODENV/0000000005/0000001817/0000000016/ 0000233189.3D Proof by: QC by: NICK ELLIS IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LANGUAGE INTRODUCTION Children acquire their first language (L1) by engaging with their caretakers in natural meaningful communication. From this “evidence” they automatically acquire complex knowledge of the structure of their language. Yet paradoxically they cannot describe this knowledge, the discovery of which forms the object of the disciplines of theoretical lin- guistics, psycholinguistics, and child language acquisition. This is a difference between explicit and implicit knowledge—ask a young child how to form a plural and she says she does not know; ask her “here is a wug, here is another wug, what have you got?” and she is able to reply, “two wugs.” The acquisition of L1 grammar is implicit and is extracted from experience of usage rather than from explicit rules—simple expo- sure o normal linguistic input suffices and no explicit instruction is needed. Adult acquisition of second language (L2) is a different matter in that what can be acquired implicitly from communicative contexts is typically quite limited in comparison to native speaker norms, and adult attainment of L2 accuracy usually requires additional resources of explicit learning. The various roles of consciousness in second language acquisi- tion (SLA) include: the learner noticing negative evidence; their attending to language form, their perception focused by social scaffolding or explicit instruction; their voluntary use of pedagogical grammatical descriptions and analogical reasoning; their reflective induction of metalinguistic insights about language; and their consciously guided practice which results, eventually, in unconscious, automatized skill. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

Implicit and Explicit Learning of Languages Patrick Rebuschat

Introduction: Implicit and explicit learning of languages Patrick Rebuschat (Lancaster University) Introduction to the forthcoming volume: Rebuschat, P. (Ed.) (in press, 2015). Implicit and explicit learning of languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Implicit learning, essentially the process of acquiring unconscious (implicit) knowledge, is a fundamental feature of human cognition (Cleeremans, Destrebecqz, & Boyer, 1998; Dienes, 2012; Perruchet, 2008; Shanks, 2005; Reber, 1993). Many complex behaviors, including language comprehension and production (Berry & Dienes, 1993; Winter & Reber, 1994), music cognition (Rohrmeier & Rebuschat, 2012), intuitive decision making (Plessner, Betsch, & Betsch, 2008), and social interaction (Lewicki, 1986), are thought to be largely dependent on implicit knowledge. The term implicit learning was first used by Arthur Reber (1967) to describe a process during which subjects acquire knowledge about a complex, rule-governed stimulus environment without intending to and without becoming aware of the knowledge they have acquired. In contrast, the term explicit learning refers to a process during which participants acquire conscious (explicit) knowledge; this is generally associated with intentional learning conditions, e.g., when participants are instructed to look for rules or patterns. In his seminal study, Reber (1967) exposed subjects to letter sequences (e.g., TPTS, VXXVPS and TPTXXVS) by means of a memorization task. In experiment 1, subjects were presented with letter sequences and simply asked to commit them to memory. One group of subjects was given sequences that were generated by means of a finite-state grammar (Chomsky, 1956, 1957; Chomsky & Miller, 1958), while the other group received randomly 1 constructed sequences. The results showed that grammatical letter sequences were learned more rapidly than random letter sequences. -

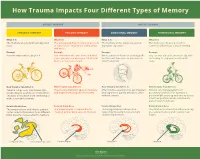

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Evidence of Automatic Processing in Sequence Learning Using Process-Dissociation

RESEARCH ARTICLE ADVANCES IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Evidence of automatic processing in sequence learning using process-dissociation Heather M. Mong, David P. McCabe, and Benjamin A. Clegg Department of Psychology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA ABSTRACT This paper proposes a way to apply process-dissociation to sequence learning in addition and ex- tension to the approach used by Destrebecqz and Cleeremans (2001). Participants were trained on two sequences separated from each other by a short break. Following training, participants self-reported their knowledge of the sequences. A recognition test was then performed which re- quired discrimination of two trained sequences, either under the instructions to call any sequence encountered in the experiment “old” (the inclusion condition), or only sequence fragments from one half of the experiment “old” (the exclusion condition). The recognition test elicited automatic KEYWORDS and controlled process estimates using the process dissociation procedure, and suggested both implicit learning, sequence processes were involved. Examining the underlying processes supporting performance may pro- learning, process- vide more information on the fundamental aspects of the implicit and explicit constructs than has dissociation, consciousness been attainable through awareness testing. INTRODUCTION Shanks, 2005), and numerous definitions of the term itself have been offered (Dienes & Perner, 1999; Frensch, 1998). This variety is further The serial reaction time task (SRTT) has become an extremely pro- reflected in an array of methods for assessing the presence or absence ductive method for studying sequence learning (for reviews, see of explicit knowledge. Issues raised have included whether explicit Abrahamse, Jimenez, Verwey, & Clegg, 2010; Clegg, DiGirolamo, knowledge is necessary for learning, what awareness tests should be & Keele, 1998). -

Memory Performance and Adaptive Strategies in Younger and Older Adults During Single and Dual Task Conditions

MEMORY PERFORMANCE AND ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES IN YOUNGER AND OLDER ADULTS DURING SINGLE AND DUAL TASK CONDITIONS VICTORIA GRACE COLLIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2015 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not currently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised the work of others.” Student Victoria G Collin Date First Supervisor Dr Sandhiran Patchay Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Sandhi Patchay, Dr Trevor Thompson and Professor Pam Maras for all of your support and guidance over the years. It’s been a long and sometimes difficult journey, and I really appreciate all of your patience and understanding. I would also like to thank Dr Mitchell Longstaff who encouraged me to embark on this journey, and for all of his help early on as my supervisor. Thanks also to all my colleagues in the department for their advice and encouragement over the years. In particular I would like to thank Dr Claire Monks who was very helpful in her role as Programme Leader- sorry for all of the annoying questions! I would like to thank all of the participants, who offered their precious time to take part in my research. -

1 Personality and Cognitions Underlying Entrepreneurial Intentions Benjamin R. Walker a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment O

1 Personality and Cognitions underlying Entrepreneurial Intentions Benjamin R. Walker A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Management UNSW Business School March 30, 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Originality statement .................................................................................................................. 7 Publications and conference presentations arising from this thesis ........................................... 8 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 9 Thesis Abstract......................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2: Assessing the impact of revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory ...................... 20 Table 1: Articles with original Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (o-RST) and revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) measures .......................................................... 26 Table 2: Categorization of original Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (o-RST) and revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) studies in the five years from 2010-2014 ........ 29 Chapter 3: How -

Episodic Memory-From Brain to Mind

HIPPOCAMPUS 16:691–703 (2006) Episodic Memory—From Brain to Mind Janina Ferbinteanu,* Pamela J. Kennedy, and Matthew L. Shapiro ABSTRACT: Neuronal mechanisms of episodic memory, the conscious by the rapid formation of relational representations of recollection of autobiographical events, are largely unknown because highly processed sensory information that are used electrophysiological studies in humans are conducted only in excep- tional circumstances. Unit recording studies in animals are thus crucial flexibly and are not necessarily expressed through overt for understanding the neurophysiological substrate that enables people motor behavior. Episodic memory is also sensitive to to remember their individual past. Two features of episodic memory— lesions of the prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al., 1995; autonoetic consciousness, the self-aware ability to \travel through Nyberg et al., 2000; Burgess et al., 2002; Wheeler time", and one-trial learning, the acquisition of information in one and Stuss, 2003), develops later in an individual’s life, occurrence of the event—raise important questions about the validity of animal models and the ability of unit recording studies to capture essen- encodes events within a personal framework, and pos- tial aspects of memory for episodes. We argue that autonoetic experi- sesses a temporal dimension because it is oriented ence is a feature of human consciousness rather than an obligatory as- towards the past and the future (Tulving, 1972, 2001, pect of memory for episodes, and that episodic memory is reconstruc- 2002; Tulving and Markowitsch, 1998). Autobio- tive and thus its key features can be modeled in animal behavioral tasks graphic information contains memories about what that do not involve either autonoetic consciousness or one-trial learning. -

Neural Networks Involved in Autobiographical Memory

The Journal of Neuroscience, July 1, 1996, 16(13):4275–4282 Cerebral Representation of One’s Own Past: Neural Networks Involved in Autobiographical Memory Gereon R. Fink,1,2 Hans J. Markowitsch,3 Mechthild Reinkemeier,3 Thomas Bruckbauer,1 Josef Kessler,1 and Wolf-Dieter Heiss1,2 1Max-Planck-Institut fu¨ r Neurologische Forschung, D-50931 Ko¨ ln, Germany, 2Universita¨ tsklinik fu¨ r Neurologie der Universita¨ t zu Ko¨ ln, D-50924 Ko¨ ln, Germany, and 3Physiologische Psychologie, Universita¨ t Bielefeld, D-33501 Bielefeld, Germany We studied the functional anatomy of affect-laden autobio- were activated in the comparison PERSONAL to REST (auto- 15 graphical memory in normal volunteers. Using H2 O positron biographical episodic memory ecphory). In addition, the right emission tomography (PET), we measured changes in relative temporomesial, right dorsal prefrontal, right posterior cingulate regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF). Four rCBF measurements areas, and the left cerebellum were activated. A comparison of were obtained during three conditions: REST, i.e., subjects lay PERSONAL and IMPERSONAL (autobiographical vs nonauto- at rest (for control); IMPERSONAL, i.e., subjects listened to biographical episodic memory ecphory) demonstrated a pre- sentences containing episodic information taken from an auto- ponderantly right hemispheric activation including primarily biography of a person they did not know, but which had been right temporomesial and temporolateral cortex, right posterior presented to them before PET scanning (nonautobiographical cingulate areas, right insula, and right prefrontal areas. The right episodic memory ecphory); and PERSONAL, i.e., subjects lis- temporomesial activation included hippocampus, parahip- tened to sentences containing information taken from their own pocampus, and amygdala. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86288-2 - Memory in Autism Edited by Jill Boucher and Dermot Bowler Excerpt More information Part I Introduction © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86288-2 - Memory in Autism Edited by Jill Boucher and Dermot Bowler Excerpt More information 1 Concepts and theories of memory John M. Gardiner Concept. A thought, idea; disposition, frame of mind; imagination, fancy; .... an idea of a class of objects. Theory. A scheme or system of ideas or statements held as an explan- ation or account of a group of facts or phenomena; a hypothesis that has been confirmed or established by observation or experiment, and is propounded or accepted as accounting for the known facts; a statement of what are known to be the general laws, principles, or causes of some- thing known or observed. From definitions given in the Oxford English Dictionary The Oxford Handbook of Memory, edited by Endel Tulving and Fergus Craik, was published in the year 2000. It is the first such book to be devoted to the science of memory. It is perhaps the single most author- itative and exhaustive guide as to those concepts and theories of memory that are currently regarded as being most vital. It is instructive, with that in mind, to browse the exceptionally comprehensive subject index of this handbook for the most commonly used terms. Excluding those that name phenomena, patient groups, parts of the brain, or commonly used exper- imental procedures, by far the most commonly used terms are encoding and retrieval processes.