European Community's Poverty Reduction Effectiveness Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12028809 02.Pdf

Appendix 1 Member List of the Study Team Appendix 1 Member List of the Study Team (1) During Field Survey (2nd Phase of the Study on Rural Water Supply in Tabora Region) Mr. Yasumasa Team Leader/Rural Water Supply Earth System Science Co., Ltd YAMASAKI Planner Mr. Takuya YABUTA Deputy Team Leader/Groundwater Earth System Science Co., Ltd Development Planner Mr. Masakazu SAITO Hydrogeologist 1,Implementation and Procurement Planner/Cost Earth System Science Co., Ltd. Estimator 1 Mr. Tadashi Hydrogeologist 2 Earth System Science Co., Ltd. YAMAKAWA (Mitsubishi Materials Techno Corporation) Mr. Hiroyuki Specialist for Water Quality, Earth System Science Co., Ltd. NAKAYAMA Database/GIS 1 Mr. Shigekazu Hydrologist/Meteorologist Kokusai Kogyo Co., Ltd. FUJISAWA Ms. Mana ISHIGAKI Socio-Economist Japan Techno Co., Ltd. (I. C. Net Ltd.) Mr. Teruki MURAKAMI Urban Water Supply Planner Japan Techno Co., Ltd. Mr. Susumu ENDO Geophysicist 1 Earth System Science Co., Ltd. (Mitsubishi Materials Techno Corporation) Mr. Kengo OHASHI Geophysicist 2 Earth System Science Co., Ltd. Mr. Tatsuya SUMIDA Drilling Engineer, Supervisor of Hand Pump Repairing, Earth System Science Co., Ltd. Implementation and Procurement Planner/Cost Estimator 2 Mr. Daisuke NAKAJIMA Water Supply Facility Designer Kokusai Kogyo Co., Ltd. Mr. Naoki MORI Specialist for Operation and Japan Techno Co., Ltd. Maintenance Mr. Norikazu Specialist for Environment and Kokusai Kogyo Co., Ltd. YAMAZAKI Social Consideration Mr. Naoki TAKE Specialist for `Public Health and Earth System Science Co., Ltd. Hygiene (Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc.) Mr. Tadashi SATO Coordinator, Specialist for Earth System Science Co., Ltd. Database/GIS 2 A1 - 1 Appendix-1 Member List of the Study Team (2) Explanation of Preparatory Survey Senior Adviser to the Director General, Mr. -

Tabora Region Investment Guide

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT TABORA REGION INVESTMENT GUIDE The preparation of this guide was supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF) 182 Mzinga way/Msasani Road Oyesterbay P.O. Box 9182, Dar es Salaam ISBN: 978 - 9987 - 664 - 16 - 0 Tel: (+255-22) 2195000 - 4 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.esrftz.or.tz Website: www.tz.undp.org TABORA REGION INVESTMENT GUIDE | i TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................................iv LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................v DEMONSTRATION OF COMMITMENT FROM THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF GOVERNMENT ..................................................................................................................................... viii FOREWORD ..............................................................................................................................................ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................xii DISCLAIMER ..........................................................................................................................................xiv -

BA Report OYE SDC Project Final November 2017[1[

SWISS AGENCY FOR DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATION – SDC OPPORTUNITIES FOR YOUTH EMPLOYMENT - OYE Project BENEFICIARY ASSESSMENT REPORT November 2017 Mr. Christopher Ndangala with Dr. Riff Fullan Page 1 of 39 Table of Contents i. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 4 ii. List of acronyms and abbreviations ....................................................................................... 5 iii. Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 6 Key Findings ........................................................................................................................... 6 Summary Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 1. Context of the Opportunities for Youth Employment Beneficiary Assessment .................... 9 1.1 The OYE – SDC project ..................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Beneficiary assessment ................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Objectives of OYE beneficiary assessment ................................................................... 10 2. Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 10 2.1 Assessment planning .................................................................................................... -

Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala

Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala The "Success Story" of Peasant Tobacco Production in Tanzania Publications from the Centre for Development Research, Copenhagen The "Success Story" of Peasant Tobacco Production in Tanzania The political economy of a commodity producing peasantry Jannik Boesen A. T. Mohele Published by Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala 1979 Publications from the Centre for Development Research, Coppnhagen No. l.Bukh, Jette, The Village Woman in Ghana. 118 pp. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies 197 9. No. 2. Boesen,Jannik & Mohele, A.T., The "Success Story" ofPeasant Tobacco Production in Tanzania. 169 pp. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies 197 9. This series contains books written by researchers at the Centre for Development Research, Copenhagen. It is published by the Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala, in co-operation with the Centre for Development Research with support from the Danish International Development Agency (Danida). Cover picture and photo on page 1 16 by Jesper Kirknzs, other photos by Jannik Boesen. Village maps measured and drafted by Jannik Boesen and drawn by Gyda Andersen, who also did the other drawings. 0Jannik Boesen 8cA.T. Mohele and the Centre for Development Research 1979 ISSN 0348.5676 ISBN 91-7106-163-0 Printed in Sweden by Offsetcenter ab, Uppsala 197 9 Preface This book is the result of a research project undertaken jointly by the Research Section of the Tanzania Rural Development Bank (TRDB)and the Danish Centre for Development Research (CDR). The research work was carried out between 1976 and 1978 by A.T. Mohele of the TRDB and Jannik Boesen of the CDR. -

Appendices to Vol 4B

Vote 85 Tabora Region Councils in the Region Council District Councils Code 2017 Tabora Municipal Council 2034 Nzega Town Council 3065 Igunga District Council 3066 Nzega District Council 3067 Tabora District Council 3068 Urambo District Council 3091 Sikonge District Council 3123 Kaliua District Council 2 Vote 85 Tabora Region Council Development Budget Summary Local and Foreign 2014/15 Code Council Local Foreign Total 2017 Tabora Municipal Council 3,145,997,000 3,832,425,000 6,978,422,000 3065 Igunga District Council 4,290,441,000 2,670,840,000 6,961,281,000 3066 Nzega District Council 3,949,280,000 3,662,237,000 7,611,517,000 3067 Tabora District Council 3,879,266,000 2,675,944,000 6,555,210,000 3068 Urambo District Council 2,835,753,000 2,178,818,000 5,014,571,000 3091 Sikonge District Council 3,216,457,000 2,055,394,000 5,271,851,000 3123 Kaliua District Council 6,108,531,000 1,669,230,000 7,777,761,000 Total 27,425,725,000 18,744,888,000 46,170,613,000 3 Vote 85 Tabora Region Code Description 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 Actual Expenditure Approved Expenditure Estimates Local Foreign Local Foreign Local Foreign Total Shs. Shs. Shs. 85 Tabora Region 3280 Rural Water Supply & Sanitation 0 3,134,201,000 0 7,206,604,000 0 3,144,342,000 3,144,342,000 4390 Secondary Education Development 0 0 0 1,325,423,000 0 2,015,220,000 2,015,220,000 Programme 4399 Local Government Resources Centre Project 0 2,002,055,000 0 0 0 0 0 4404 District Agriculture Development Support 0 187,820,000 0 0 0 3,869,473,000 3,869,473,000 4486 Agriculture Sector Dev. -

The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a Field Trip and Workshop on Scaling up in Africa

The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a field trip and workshop on scaling up in Africa The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a field trip and workshop on scaling up in Africa 23-24 July 2010 In July 2010, six organizations came together to study and discuss current prospects for scaling up access to sanitation and hygiene inVon East Africa. The group started with a trip to the field – visiting various projects in Tanzania that, between them, represent a range of approaches to improving access to sanitation and changing hygiene practices. The objective was not to evaluate or critique individual projects, but rather to look for overarching principles: what works; what doesn’t work; what are the gaps in our knowledge; how can working in partnership help us achieve our aims; what barriers do we need to overcome in order to extend the benefits of such projects to all people across Africa. These notes reflect the conclusions, recommendations and lessons learned from this trip. They are based on a two-day workshop that was held directly following the trip. Further detailed notes, photos, and video material can be found in the appendices. In addition, it is planned that various databanks of reports, photos and videos will be developed and made available via the web. In December 2009, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation organized a meeting on the topic of scaling up on-site sanitation. Following this meeting, WSP convened a meeting of partners to explore how issues raised at the Gates meeting could be taken forward in East Africa. -

Birds of Golden Pride Project Area, Nzega District, Central Tanzania: an Evaluation of Recolonization of Rehabilitated Areas

Scopus 36(2): 26–37, July 2016 Birds of Golden Pride Project area, Nzega District, central Tanzania: an evaluation of recolonization of rehabilitated areas Chacha Werema, Kim M. Howell, Charles A. Msuya, Jackie Sinclair and Anael Macha Summary In Tanzania, the success of habitat restoration in mining areas to create suitable environmental conditions for wildlife is poorly understood. Between March 2010 and December 2014 bird species were recorded at the Golden Pride Project area, a gold mine in Nzega District, central Tanzania. The aims of this study were to document bird communities in the mine area, and to assess the extent to which rehabilitated areas have been recolonised. Mist netting, point counts, timed species counts and opportunistic observations were used to document 181 species of birds at the mine area. These included two species endemic to Tanzania, the Tanzanian Red-billed Hornbill Tockus ruahae (treated here as a species separate from T. erythrorhynchus, see Kemp & Delport 2002, Sinclair & Ryan 2010) and Ashy Starling Cosmopsarus unicolor. Rehabilitated areas had about half the number of species found in the unmined areas. Bird use of areas under rehabilitation suggests that habitat restoration can be used to create corridors linking fragmented landscapes. Results suggest that as the vegetation of the rehabilitated areas becomes more structurally complex, the number of bird species found there will be similar to those in unmined areas. This study provides a baseline for future monitoring, leading to a better understanding of the process of avian colonisation of rehabilitated areas. Furthermore, results imply that in mining areas it is useful to have an unmined area where vegetation is naturally allowed to regenerate, free of human activity. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings. in the Center for Research Libraries Scans

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts are not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the Center for Research Libraries. © Center for Research Libraries Scan Date: December 27, 2007 Identifier: m-n-000128 fl7, THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES DIVISION Guide to The Microfilms of Regional and District Books 1973 PRINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, DAR ES SALAAMs,-TANZANA. Price: S&. 6152 MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES DIVISION Guide to The Microfilms of Regional and District Books vn CONTENTS. Introduction ... .... ... ... ... History of Regional Administration .... ... District Books and their Subject Headings ... THE GUIDE: Arusha Region ... ... ... Coast Region ............... ... Dodoma Region .. ... ... ... Iringa Region ............... ... Kigoma ... ... ... ... ... Kilimanjaro Region .... .... .... ... Mara Region .... .... .... .... ... Mbeya Region ... ... ... ... Morogoro Region ... ... ... ... Mtwara Region ... ... Mwanza Region .. -

Project/Programme Proposal to the Adaptation Fund

PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL TO THE ADAPTATION FUND PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Project/Programme Category: Regular Project Country/ies: United Republic of Tanzania Title of Project/Programme: Strategic Water Harvesting Technologies for Enhancing Resilience to Climate Change in Rural Communities in Semi-Arid Areas of Tanzania (SWAHAT) Type of Implementing Entity: National Implementing Entity (NIE) Implementing Entity: National Environment Management Council (NEMC) Executing Entity/: Sokoine University of Agriculture Amount of Financing Requested 1,280,000 (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) Project Summary The objective of proposed SWAHAT project is enhancing resilience and adaptation of semi arid rural communities to climate change-induced impacts of drought, floods and water scarcity. This will be achieved through strategic water harvesting technologies that will contribute to improved crops, aquaculture and livestock productivity, reforestation as well as combating emerging crops and livestock pests and diseases. The conceptual design of the water harvesting dam has been designed to ensure afforestation of the catchment before the dam thus prevention excessive siltation. The constructed or rehabilitated dams will supply water for all the proposed resilience and adaptation enhancing integrated innovations to be implemented on the semi-arid landscapes. In addition, synergism between aquaculture and agricultural activities will be done to enhance nutrient recycling and improve resource use efficiency. Nursery for fruits and forest trees as well as vegetable gardens will be established and supply seedlings for afforestation and horticulture. Pastureland and animal husbandry infrastructure will be established downstream of the dam for improved productivity and supply of manure for soil fertility improvement. The afforested landscape will integrate apiary units, provide fuel wood and restore habitats for biodiversity conservation. -

The Study on Rural Water Supply in Tabora Region in the United Republic of Tanzania

MINISTRY OF WATER THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA THE STUDY ON RURAL WATER SUPPLY IN TABORA REGION IN THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA FINAL REPORT SUMMARY MAY 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EARTH SYSTEM SCIENCE CO., LTD JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. GED JR 11-105 MINISTRY OF WATER THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA THE STUDY ON RURAL WATER SUPPLY IN TABORA REGION IN THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA FINAL REPORT SUMMARY MAY 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EARTH SYSTEM SCIENCE CO., LTD JAPAN TECHNO CO., LTD. KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. In this report, project costs are estimated based on prices as of November 2010 with an exchange rate of US$1.00 = Tanzania Shilling (Tsh) 1,434.66 = Japanese Yen ¥ 88.00. Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT AND CURRENT SITUATION OF THE STUDY AREA The government of Tanzania started the Rural Water Supply Project in 1971 aiming to provide safe and clean water to the entire nation within a 400m distance. The Ministry of Water (MoW) has been continuing efforts to improve water supply coverage formulating a “Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP)” in 2000 and “MKUKUTA (National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) in 2005. NSGRP targets are to improve water supply coverage from 53% to 65% in the rural area and from 73% to 100% in the urban area up to the year 2010. However, it is probably difficult to realize the target. The Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MoWI) formulated the “Water Sector Development Programme (WSDP)” in 2006 to improve water supply coverage using the basket fund based on a Sector Wide Approach for Planning (SWAp). -

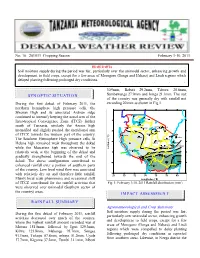

Agrometeorological and Crop Summary

No: 16 2010/11 Cropping Season February 1-10, 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Soil moisture supply during the period was fair, particularly over the unimodal sector, enhancing growth and development to field crops, except for a few areas of Morogoro (Ilonga and Ifakara) and Lindi regions which delayed planting following prolonged dry conditions. 30.9mm, Babati 29.2mm, Tabora 28.6mm, SYNOPTIC SITUATION Sumbawanga 27.9mm and Iringa 21.1mm. The rest of the country was generally dry with rainfall not During the first dekad of February 2011, the exceeding 20 mm as shown in Fig 1. northern hemisphere high pressure cells, the Siberian High and its associated Arabian ridge Bukoba continued to intensify keeping the zonal arm of the Musoma 2 Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) further Mwanza Ukiriguru south of Tanzania, similarly the Azores high Kibondo Lyamungo Moshi Shinyanga Arushakia Same intensified and slightly pushed the meridional arm 4 Babati Singida of ITCZ towards the western part of the country. Kigoma Tanga TaboraTumbi Pemba The Southern Hemisphere High pressure cells, St Handeni 6 Hombolo Dodoma Zanzibar Helena high remained weak throughout the dekad Kibaha Morogoro Dar es Salaam while the Mascarine high was observed to be Latitudes (°S) Iringa Sumbawanga relatively weak at the beginning of the dekad and 8 Mahenge Kilwa gradually strengthened towards the end of the MboziMbeyaUyole Tukuyu Igeri Lindi dekad. The above configuration contributed to 10 Mtwara enhanced rainfall over a portion of southern parts Songea of the country. Low level wind flow was associated 12 with relatively dry air and therefore little rainfall. 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 Mainly local scale phenomena and occasional shift Longitudes (°E) of ITCZ contributed for the rainfall activities that Fig. -

Population, Incipient Desertification and Prediction of Household Agroforestry Uptake in Tabora Region, Tanzania

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 7, Issue 8, August 2017 169 ISSN 2250-3153 Population, Incipient Desertification and Prediction of Household Agroforestry Uptake in Tabora Region, Tanzania George Felix Masanja Department of Geography, St. Augustine University of Tanzania, Box 307, Mwanza, Tanzania Abstract- Environmental conservation in the world presents a daunting task due to population increase. In Tanzania, environmental degradation has occurred at an alarming rate in specific areas including Tabora. The continued burgeoning of the human population has resulted in changes in land use, increasing demand for resources and excision of forests. This study employed the theory of planned behaviour to predict on-farm tree planting behaviour of farmers. A sample size of 288 farmers drawn from Nzega and Sikonge districts in Tabora region was interviewed to measure standard theory of planned behaviour constructs. The data and hypotheses were examined using structural equation modeling performed in partial least squares algorithms. Results from the maximum likelihood estimation showed that attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural controls were significantly and positively associated with stronger intention and related to farmers’ behaviours in farming decisions. Farmers saw hindrance in tree planting operations being a result of cultural beliefs which yielded negative impacts. However, these were outweighed by perceptions of positive impacts. The drivers of these constructs can be harnessed by policy makers by directing farmers’ intentions and behaviours toward conserving and sustaining fragile eco-environmentally areas against a threatening population growth in the region through agroforestry uptake programs. Index Terms- Population growth, Deforestation, Tree planting, Gender, Theory of planned behaviour.