Invading Species Watch Program Annual Report (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Swallowswallow Volume 20, # 1 Autumn 2002

TheThe SwallowSwallow Volume 20, # 1 Autumn 2002 Directors: President: Carey Purdon 625-2610 Jean Brereton Rob Cunningham Vice-President: Leo Boland 735-7117 Merv Fediuk Myron Loback Treasurer: Bernd Krueger 625-2879 Chris Michener Elizabeth Reeves Secretary: Manson Fleguel 735-7703 Benita Richardson Gwen Purdon Sandhill Cranes in Westmeath Provincial Park, photographed by Chris Michener on September 8, 2002. Membership in the Pembroke Area Field Naturalists is available by writing to: the PAFN, Box1242, Pembroke, ON K8A 6Y6. 2002/2003 dues are: Student $5, Senior $5, Individual $7, Family $10, Individual Life $150, Family Life $200. Editor, The Swallow: Chris Michener, R.R.1, Golden Lake, ON K0J 1X0 - Submissions welcome! ph: (613) 625-2263; e-mail: [email protected] PAFN internet page: http://www.renc.igs.net/~cmichener/pafn.index.html e v e n t s Westmeath Dunes (2 walks) results and enjoy pizza courtesy of the Dates: Sunday, Sep. 29 at 8 AM., and Club. Field Participants are asked to con- Saturday, Oct.5 at 8 AM. tribute $3.00 for publishing costs in the Place: Both trips start from the munici- Audubon CBC yearly report. pal dock in the town of Westmeath. Com- ing from the west on County Road 12, To view the Count circle map and turn left in Westmeath before the gas download forms, go to our web page. (see station at the blue building and continue cover for URL) Please contact Manson down to the water. Species sometimes to confirm participation, 613-732-7703 encountered are Nelson’s Sharp-tailed - email: [email protected]. -

2019 Progress Report of the Parties

2019 PROGRESS REPORT OF THE PARTIES Pursuant to the 2012 Canada-United States Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement U.S. spelling is used throughout this report except when referring to Canadian titles. Units are provided in metric or U.S. customary units for activities occurring in Canada or the United States, respectively. Discussions of funding levels or costs in dollars is provided using Canadian dollars for activities occurring in Canada and U.S. dollars for activities occurring in the United States. Cat. No.: En164-53/2-2019E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-30888-3 II 2019 PROGESS REPORT OF THE PARTIES Table of Contents Executive Summary ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Why the Great Lakes are Important ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������2 Articles �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Areas of Concern Annex ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 Lakewide Management Annex ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 23 Chemicals of Mutual Concern Annex ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 38 Nutrients Annex ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Striped Whitelip Webbhelix Multilineata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Striped Whitelip Webbhelix multilineata in Canada ENDANGERED 2018 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2018. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Whitelip Webbhelix multilineata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 62 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Annegret Nicolai for writing the status report on the Striped Whitelip. This report was prepared under contract with Environment and Climate Change Canada and was overseen by Dwayne Lepitzki, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment and Climate Change Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Polyspire rayé (Webbhelix multilineata) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Striped Whitelip — Robert Forsyth, August 2016, Pelee Island, Ontario. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018. Catalogue No. CW69-14/767-2018E-PDF ISBN 978-0-660-27878-0 COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2018 Common name Striped Whitelip Scientific name Webbhelix multilineata Status Endangered Reason for designation This large terrestrial snail is present on Pelee Island in Lake Erie and at three sites on the mainland of southwestern Ontario: Point Pelee National Park, Walpole Island, and Bickford Oak Woods Conservation Reserve. -

Hiking in Ontario Ulysses Travel Guides in of All Ontario’S Regions, with an Overview of Their Many Natural and Cultural Digital PDF Format Treasures

Anytime, Anywhere in Hiking The most complete guide the World! with descriptions of some 400 trails in in Ontario 70 parks and conservation areas. In-depth coverage Hiking in Ontario in Hiking Ulysses Travel Guides in of all Ontario’s regions, with an overview of their many natural and cultural Digital PDF Format treasures. Practical information www.ulyssesguides.com from trail diffi culty ratings to trailheads and services, to enable you to carefully plan your hiking adventure. Handy trail lists including our favourite hikes, wheelchair accessible paths, trails with scenic views, historical journeys and animal lover walks. Clear maps and directions to keep you on the right track and help you get the most out of your walks. Take a hike... in Ontario! $ 24.95 CAD ISBN: 978-289464-827-8 This guide is also available in digital format (PDF). Travel better, enjoy more Extrait de la publication See the trail lists on p.287-288 A. Southern Ontario D. Eastern Ontario B. Greater Toronto and the Niagara Peninsula E. Northeastern Ontario Hiking in Ontario C. Central Ontario F. Northwestern Ontario Sudbury Sturgeon 0 150 300 km ntario Warren Falls North Bay Mattawa Rolphton NorthernSee Inset O 17 Whitefish 17 Deux l Lake Nipissing Callander Rivières rai Ottawa a T Deep River Trans Canad Espanola Killarney 69 Massey Waltham 6 Prov. Park 11 Petawawa QUÉBEC National Whitefish French River River 18 Falls Algonquin Campbell's Bay Gatineau North Channel Trail Port Loring Pembroke Plantagenet Little Current Provincial Park 17 Park Gore Bay Sundridge Shawville -

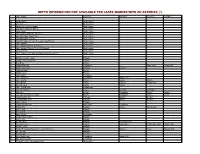

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

FINAL EOMF Annual Report 2003-2004

ACCOMPLISHMENTS 2003-2004 forests for seven generations The Eastern Ontario Model Forest is proud to present this annual report on Domtar Plainfield Opaque FSC-certified paper. Cover design by Tom D. Humphries, 2004. Table of Contents Message from the President — Meeting the Challenge 1 Report of the General Manager — A Good Way to Get Things Done 2 Our People in 2003-2004 — Board of Directors 4 Our People in 2003-2004 — Staff & Associates 6 A Budding List of Accomplishments — Project Preview 8 OBJECTIVE 1: PROJECT OVERVIEW — INCREASING THE QUALITY & HEALTH OF EXISTING WOODLANDS 9 1.0 Landowner Workshop Series 9 1.1 Landowner Education 9 1.2 Demonstration Forest Initiative 9 1.3 Web-enabled Forest Management Tool 10 1.4 Eastern Ontario Urban Forest Network (EOUFN) 12 1.5 Non-timber Revenue Opportunities 14 1.6 Timber Product Revenue Opportunities 14 1.7 Sustainable Forest Certification Initiative 14 1.8 Recognition Program 16 1.9 Science Management 17 1.10 Biodiversity Indicators for Woodland Owners 18 1.11 Sugar Maple & Climate Impacts 19 1.12 Mississippi River Management Plan for Water Power 20 1.13 Limerick Forest Long Range Plan & Trail Mapping 20 1.14 Cartography Initiatives of the Mapping & Information Group 21 OBJECTIVE 2: PROJECT OVERVIEW — INCREASING FOREST COVER ACROSS THE LANDSCAPE 22 2.0 Sustainable Forest Management in Local Government Plans 22 2.1 Desired Future Forest Condition Pilot Project 23 2.2 Strategic Planting Initiative 23 2.3 Ontario Power Generation Planting Database 23 2.4 Bog to Bog (B2B) Landscape Demonstration -

New Canadian and Ontario Orthopteroid Records, and an Updated Checklist of the Orthoptera of Ontario

Checklist of Ontario Orthoptera (cont.) JESO Volume 145, 2014 NEW CANADIAN AND ONTARIO ORTHOPTEROID RECORDS, AND AN UPDATED CHECKLIST OF THE ORTHOPTERA OF ONTARIO S. M. PAIERO1* AND S. A. MARSHALL1 1School of Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 email, [email protected] Abstract J. ent. Soc. Ont. 145: 61–76 The following seven orthopteroid taxa are recorded from Canada for the first time: Anaxipha species 1, Cyrtoxipha gundlachi Saussure, Chloroscirtus forcipatus (Brunner von Wattenwyl), Neoconocephalus exiliscanorus (Davis), Camptonotus carolinensis (Gerstaeker), Scapteriscus borellii Linnaeus, and Melanoplus punctulatus griseus (Thomas). One further species, Neoconocephalus retusus (Scudder) is recorded from Ontario for the first time. An updated checklist of the orthopteroids of Ontario is provided, along with notes on changes in nomenclature. Published December 2014 Introduction Vickery and Kevan (1985) and Vickery and Scudder (1987) reviewed and listed the orthopteroid species known from Canada and Alaska, including 141 species from Ontario. A further 15 species have been recorded from Ontario since then (Skevington et al. 2001, Marshall et al. 2004, Paiero et al. 2010) and we here add another eight species or subspecies, of which seven are also new Canadian records. Notes on several significant provincial range extensions also are given, including two species originally recorded from Ontario on bugguide.net. Voucher specimens examined here are deposited in the University of Guelph Insect Collection (DEBU), unless otherwise noted. New Canadian records Anaxipha species 1 (Figs 1, 2) (Gryllidae: Trigidoniinae) This species, similar in appearance to the Florida endemic Anaxipha calusa * Author to whom all correspondence should be addressed. -

Survey Bulletin

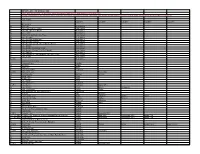

SURVEY BULLETIN Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in Ontario Summer 1991 Forestry Forels 1*1 Canada Canada Canada FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN ONTARIO1 Summer 1991 This is the second of three annual bulletins issued by the Forest Insect and Disease Survey (FIDS) of Forestry Canada, Ontario Region. It describes pest conditions in Ontario forests in 1991. The information originated from ground and aerial surveys carried out between early May and mid-July. Figures presented in this bulletin are preliminary and subject to change, as ongoing surveys may disclose additional information. FOREST INSECTS Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.) For the third consecutive year, spruce budworm populations increased. The total area of moderate-to-severe defoliation mapped by ground and aerial surveys was 9,065,781 ha, up from the 6,783,261 ha recorded in 1990 (Table 1). The main body of the infestation is still located in the Northwestern and North Central regions, but has now extended eastward to include areas in the northwestern corner of Wawa District and the southwestern side of Hearst District in the Northern and Northeastern regions (Fig. 1). The two large infestations mapped in 1989 and 1990 have again merged to form a single huge area of moderate-to- severe defoliation stretching from the Gourlay-Chelsea-Boyce townships area of Hearst District west to the Manitoba border. This area encompasses all or part of the following districts: Kenora, Red Lake, Sioux Lookout, Dryden, Fort Frances, Atikokan, Ignace, Thunder Bay, Nipigon, Terrace Bay, Wawa and Hearst. Increases in the area affected were recorded in all of these districts except Dryden, where a decline was recorded (Table 1). -

INTRODUCTION 1.1 Description of the River 1.2 Project Structure 1.3

INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 1 Introduction The Ottawa River cradles the natural and cultural heart of eastern Ontario and western Quebec. Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples established their presence here some 6,000 years ago, followed by Europeans in pursuit of furs, timber, and land. From the area’s first inhabitants to the explorers, guides, traders, loggers, settlers, and entrepreneurs that followed, the Ottawa River was truly the original trans‐Canada highway. The Ottawa River played an integral role in many of the key stories that make up Canada’s history. It was the route for much of the early European exploration of North America, including Samuel de Champlain. Explorers in search of the Northwest Passage began their journeys along the Ottawa River. Other celebrated figures in Canadian history including Nicollet, Radisson, La Vérendrye, Dulhut and De Troyes, traveled west along the Ottawa River to establish trade relationships with First Nations communities, laying the groundwork for the fur trade. The fur trade relied on the famous waterway routes that began and ended with the Ottawa River. France’s North American colonial economy depended on the fur trade, which led to the development of the coureurs de bois and voyageurs era, and later to the creation of the North West and Hudson’s Bay Companies. Amid the profound social, political, and economic changes of the 17th century, the Ottawa River remained one of North America’s most important trading routes. It played a central role in the story of the fur trade in North America, and thus in the development of Canada. The rich forests along the Ottawa Waterway attracted thousands of European immigrants in search of work. -

Directory of Environmental Organizations

Directory of Environmental Organizations Rideau & Cataraqui Watersheds & Area Prepared by the Rideau Roundtable March, 2005 1 Directory of Environmental Organizations Cataraqui & Rideau Watersheds & Area Purpose The purpose of this Directory is to help community organizations and government agencies gain a better understanding of “who is doing what” in terms of environmental and stewardship programs throughout the Rideau and Cataraqui watersheds and area. Content There are 75 organizations listed in this Directory: 45 entries were gathered through a survey circulated by the Rideau Roundtable in 2004; 25 entries were drawn from a Stakeholder Analysis produced by St. Lawrence Islands National Park in 2002; the remaining 5 entries were drawn from a Shoreline Stewardship Directory produced by the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority in 2004. Errors and Omissions Every attempt has been made to ensure the information contained in this Directory is accurate. Please respond to [email protected] if you wish to make changes or corrections. Although the Directory lists 75 organizations, there are many others that are not listed and are doing great work to keep our watersheds healthy. Their absence from the Directory does not reflect the quality of their work. Financial Support The Rideau Roundtable wishes to thank the Ontario Trillium Foundation for providing funding to produce this Directory. In-Kind Support The Rideau Roundtable also wishes to thank St. Lawrence Islands National Park and the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority for sharing information listed in their own directories. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click on page number at right to navigate document) Algonquin to Adirondack Conservation Initiative ............................................................. 6 Big Rideau Lake Association .......................................................................................... -

Longitudinal Profile of the Lower Ottawa River

Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF FIGURES iii LIST OF MAPS iv RIVER NOMINATION 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 The Ottawa River Heritage Designation Initiative 3 1.1.1 Ottawa River Heritage Designat ion Commi t tee S tructure 3 1.1.2 Community Support and Involvement 4 1.1.3 Methodology 5 1.2 The Canadian Heritage Rivers System 5 1.3 Location and Description of the Ottawa River 6 1.4 Role of the Ottawa River in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System 6 CHAPTER 2 CULTURAL HERITAGE VALUES 14 2.1 Description of Cultural Heritage Values 14 2.1.1 Resource Harvesting 14 2.1.2 Water Transport 15 2.1.3 Riparian Settlement 18 2.1.4 Culture and Recreation 20 2.1.5 Jurisdictional Use 22 2.2 Assessment of Cultural Heritage Values 23 2.2.1 Se lection Guide lines: Cultura l V a lues 23 2.2.2 Integrity Guidelines: Cultural Integrity Values 24 CHAPTER 3 NATURAL HERITAGE VALUES 28 3.1 Description of Natural Heritage Values 28 3.1.1 Hydrology 28 3.1.2 Physiography 29 3.1.3 River Morphology 32 3.1.4 Biotic Environments 33 3.1.5 Vegetation 33 3.1.6 Fauna 34 3.2 Assessment of Natural Heritage Values 35 3.2.1 Se lection Guide l ines: Na tura l Heri t age Va lues 35 3.2.2 Integri ty Guide l ines: Na tura l Integri ty V a lues 36 CHAPTER 4 RECREATIONAL VALUES 38 4.1 Description of Recreational Values 38 4.1.1 Boating 38 4.1.2 Swimming 38 4.1.3 Fishing 39 4.1.4 Water Related Activities 39 4.1.5 Winter Activities 40 4.1.6 Natural Heritage Appreciation 40 4.1.7 Cultural Heritage Appreciation 40 Ottawa River Nomination Document i 4.2 Assessment of Recreational Values 41 4.2.1 Selection Guidelines: Recreational Va lues 41 4.2.2 Integrity Guidelines: Recreational Integrity Values 41 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION 44 THE OTTAWA RIVER BY NIGHT (POEM BY MARGARET ATWOOD) 45 REFERENCES 46 APPENDICES 47 A. -

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F.