Art at the Heart of Anthropology on the Expression of Anthropological Insights1 Abstract Key-Words the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropology 1

Anthropology 1 ANTHROPOLOGY [email protected] Hillary DelPrete, Assistant Professor (Graduate Faculty). B.S., Tulane Chair: Christopher DeRosa, Department of History and Anthropology University; M.A., Ph.D., Rutgers University. Professor DelPrete is a biological anthropologist with a specialization in modern evolution. The Anthropology curriculum is designed to provide a liberal arts Teaching and research interests include human evolution, human education that emphasizes the scientific study of humanity. Three areas variation, human behavioral ecology, and anthropometrics. of Anthropology are covered: [email protected] • Cultural Anthropology, the comparative study of human beliefs and Christopher DeRosa, Associate Professor and Chair (Graduate Faculty). behavior with special attention to non-Western societies; B.A., Columbia University; Ph.D., Temple University. Fields include • Archaeology, the study of the human cultural heritage from its military history and American political history. Recent research prehistoric beginnings to the recent past; and concerns the political indoctrination of American soldiers. • Biological Anthropology, the study of racial variation and the physical [email protected] and behavioral evolution of the human species. Adam Heinrich, Assistant Professor (Graduate Faculty). B.S., M.A., The goal of the Anthropology program is to provide students with a broad Ph.D., Rutgers University. Historical and prehistoric archaeology; understanding of humanity that will be relevant to their professions, their -

Visual Anthropology: a Systematic Representation of Ethnography

2021-4314-AJSS – 14 JUN 2021 1 Visual Anthropology: 2 A Systematic Representation of Ethnography 3 4 In its development of one hundred years, anthropology evolved from 5 travelogues of explorers to in-depth exploration of human from all possible 6 angles. In its every venture, anthropologists were/are always in try to get 7 closer to cultural affairs and dive deeper into human subjectivity. To achieve 8 these purposes a series of theories and methods were developed, which 9 served a lot, but with time it was also felt that readers idea of a research is 10 anchored with and limited within the textual analysis written by the 11 researcher. This dependency on the text was (and still) restricting the 12 researcher to convey an actual image of the studied phenomenon, and also 13 confining the readers from exploring their subjective self in finding meaning. 14 The emergence of using visual aids in anthropology during the 90s opened a 15 pathway for the researcher to make their researched visible to the audience. 16 This visibility opens up many scopes of interpretation that are hitherto 17 invisible. Though, researchers of other disciplines started the use of visual 18 way before anthropologists. But its efficiency in transmitting meaning soon 19 pulled the attention of anthropological social researchers. Since then, visual 20 in anthropology has evolved in its use and presently one of the frontrunning 21 methods in anthropological research. This article is systematically reviewing 22 the history to present of visual anthropology with reference to theoretical 23 development and practical use of the same. -

The Digital Turn: New Directions in Media Anthropology

The Digital Turn: New Directions in Media Anthropology Sahana Udupa (Ludwig Maximilian University Munich) Elisabetta Costa (University of Groningen) Philipp Budka (University of Vienna) Discussion Paper for the Follow-Up E-Seminar on the EASA Media Anthropology Network Panel “The Digital Turn” at the 15th European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) Biennial Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 14-17 August 2018 16-30 October 2018 http://www.media-anthropology.net/ With the advent of digital media technologies, internet-based devices and services, mobile computing as well as software applications and digital platforms new opportunities and challenges have come to the forefront in the anthropological study of media. For media anthropology and related fields, such as digital and visual anthropology, it is of particular interest how people engage with digital media and technologies; how digital devices and tools are integrated and embedded in everyday life; and how they are entangled with different social practices and cultural processes. The digital turn in media anthropology signals the growing importance of digital media technologies in contemporary sociocultural, political and economic processes. This panel suggested that the digital turn could be seen a paradigm shift in the anthropological study of media, and foregrounded three important streams of exploration that might indicate new directions in the anthropology of media. More and more aspects of people’s everyday life and their lived experiences are mediated by digital technologies. Playing, learning, dating, loving, migrating, dying, as well as friendship, kinship, politics, and news production and consumption, have been affected by the diffusion of digital technologies. We often hear far-reaching statements about these transformations, such as euphoric pronouncements about digital media as a radical enabler of grassroots democracy. -

Is an Enthnographic Film a Filmic Ethnography?

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 2 Issue 2 Fall 1975 Article 6 1975 Is an Enthnographic Film a Filmic Ethnography? Jay Ruby Recommended Citation Ruby, J. (1975). Is an Enthnographic Film a Filmic Ethnography?. 2 (2), 104-111. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol2/iss2/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol2/iss2/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is an Enthnographic Film a Filmic Ethnography? This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol2/iss2/6 its infancy (Worth 1966). It would therefore seem premature to relegate these media to any particular place in social science. While it is reasonable to expect anthropologists and other educated members of our culture to be highly sophisticated, competent, and self-conscious about speaking and writing, an IS AN ETHNOGRAPHIC Fl LM analogous assumption cannot be made about their under A FILMIC ETHNOGRAPHY? standing- and use of visual communicative forms. Training in visual communication is not a commonplace experience in our education. It is rare to find an anthropologist who knows JAY RUBY very much about these forms, and even rarer to find one who has any competence in their production. It is only recently that our society has begun to acknowledge the need to INTRODUCTION 1 educate people about photographic media, and only in the last decade have anthropology departments attempted to In the social sciences, the communication of scientific develop ongoing training programs in the area. 2 thought has been, by and large, confined to the printed and Despite this situation, there is a long tradition of spoken word. -

Indigenous Peoples As a Research Space of Visual Anthropology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 9 (2014 7) 1471-1493 ~ ~ ~ УДК 304.2 Indigenous Peoples as a Research Space of Visual Anthropology Mariya I. Ilbeykina* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 14.05.2014, received in revised form 04.07.2014, accepted 30.08.2014 The article reviews visual anthropological projects that study culture of indigenous peoples both in foreign and domestic practices. Development of visual anthropology as a separate area of the humanities, from the moment of appearance of the first visual anthropological experiments to the topical research, is considered, the main lines of its development in the context of the indigenous peoples’ visual systems study are specified, i.e. such an ethno-cultural group, which development is not indicated in the finished form, but continues in the process of interaction with a multicultural community. Keywords: visual anthropology, indigenous peoples, visual sociology, “camera-intermediary”, visual systems, contemporary museum practices. Visual anthropology is a method of S.A. Smirnov writes in detail about the describing and analyzing the phenomena of fate of anthropology and its role for the social culture, founded on photos, video and audio philosophy of the 20th century, in modern records. Visual anthropology works not only anthropology he simultaneously sees powerful with cultural, but also with social problematics philosophical basis and definite application [30]. of humanitarian practices designed to create Visual anthropology that appeared within and implement “the projects of man”. -

Remembering Exhibitions on Race in the 20Th-Century United States

Visual Anthropology MUSEUM REVIEW ESSAY Remembering Exhibitions on Race in the 20th-century United States SAMUEL REDMAN ABSTRACT This museum review places the American Anthropological Association’s recent exhibition entitled “Race: Are We So Different?” into historical context by comparing it to other major exhibitions on race in the 20th century. I argue that although exhibitions on race in the 19th-century United States are frequently examined in the historical and anthropological literature, later exhibitions from the 20th century are frequently forgotten. In particular, I compare the AAA’s recent exhibition to displays originally crafted for the 1915 and 1933 World’s Fairs. [Keywords: museum, exhibit, human remains, race] HE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL Association subject of race that was intended to reach a national audi- T (AAA)–sponsored touring exhibition, “Race: Are We ence. The changing foci of these exhibits are demonstrative So Different?,” offers visitors the current anthropological of the evolving understandings of racial difference among consensus on race through exploration of lived experiences both scientists and the public. Although the narratives of of ethnically diverse peoples by outlining the scientific ba- 19th-century display are relatively well understood (Conn sis of human variation and by inviting visitors to engage in 1998; Rydell 1987; Stocking 1968), more recent exhibitions discussions on issues such as affirmative action.1 The 1,500 on race—those of the 20th century—are largely neglected square-foot exhibit, designed by the Science Museum of in the historical literature. To better understand the import Minnesota, was initially set to conclude a nationwide tour of such displays as the recent AAA exhibit, it is imperative at the Smithsonian in 2011. -

Visual Anthropology Complete Handout.Pdf

visual anthropology handout Dr Àngels Trias i Valls 05 Department of Anthropology Visual Anthropology Handout Dr Ma. Àngels Trias i Valls University of Wales Lampeter Room GO46 Arts Hall – contact: [email protected] – visiting hours: Tues&Thurs at 4.00pm Index 1. Module page with course description 2 2. Objectives 3 3. Bibliography 5 4. Internet 10 5. Intranet 11 6. Course Itinerary 12 7. Assessment 14 8. Lecture and Tutorial Handouts 15 8.1 Lectures 1 to 12 15 8.2 Tutorials 1 to 8 46 9. Revision and Exam Techniques 66 1 visual anthropology handout TiV04 0 Module Description The module is concerned how different cultures are depicted in a range of media, in particular ethnographic film and photography, and deals with the analytical and ethical issues raised by these representations. It considers how the analysis of art and material culture can be used by the anthropologists to gain insight into cultural forms and values. It also examines how different cultural groups represents themselves, to each other and to outsiders through art, material culture and performance. Course code: 1ANTH0420 Course Lecturer: Dr. Ma Àngels Trias i Valls Lent Term 2004 20 Credits 2 visual anthropology handout TiV04 1 Object of the Course In this course we will study the place of the ‘visual’ and visual systems from a cross- cultural point of view. We will examine how anthropology can contribute to –and gain insight from- the analysis of visual forms of representations. We will explore how images, forms or art, maps, pictures, ethnographic film, the body, gender, adornments to name a few, are constructed in societies across the globe. -

Focality and Extension in Kinship Essays in Memory of Harold W

FOCALITY AND EXTENSION IN KINSHIP ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF HAROLD W. SCHEFFLER FOCALITY AND EXTENSION IN KINSHIP ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF HAROLD W. SCHEFFLER EDITED BY WARREN SHAPIRO Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461812 (print) 9781760461829 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph of Hal Scheffler by Ray Kelly. This edition © 2018 ANU Press To the memory of Harold Walter Scheffler, a compassionate man of the highest scholarly standards Contents List of Figures and Tables . ix Acknowledgements . xiii Contributors . xv Part I. Introduction: Hal Scheffler’s Extensionism in Historical Perspective and its Relevance to Current Controversies . 3 Warren Shapiro and Dwight Read Part II. The Battle Joined 1 . Hal Scheffler Versus David Schneider and His Admirers, in the Light of What We Now Know About Trobriand Kinship . 31 Warren Shapiro 2 . Extension Problem: Resolution Through an Unexpected Source . 59 Dwight Read Part III. Ethnographic Explorations of Extensionist Theory 3 . Action, Metaphor and Extensions in Kinship . 119 Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart 4 . Should I Stay or Should I Go? Hunter-Gatherer Networking Through Bilateral Kin . 133 Russell D. Greaves and Karen L. -

Visual Anthropology, Media and Documentary Practices Master of Arts

VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY, MEDIA AND DOCUMENTARY PRACTICES MASTER OF ARTS NEW MASTER PROGRAM 2 WWU WEITER BILDUNG 03 INDEX OBJECTIVES OF THE MASTER PROGRAM 04 STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE 05 STUDY ORGANIZATION 10 ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS AND APPLICATION 11 MANAGEMENT AND LECTURERS 11 YoUR STAY IN MÜNSTER 12 CoNTACT AND IMPRINT 14 04 OBJECTIVES OF THE MastER PROGRAM OBJECTIVES OF THE MASTER PROGRAM In today’s globalized world, where media representations This program is for students with a background in the social shape social and political spheres, a critical understanding sciences and humanities, especially those in cultural, media of media and (audio-) visual culture is crucial. Media studies, and communication studies. Applications are welcome from rooted in social anthropology, offers an in-depth approach both Germany and abroad. to analyzing the complex connections between media, culture and society. The Master Program trains students in theory and practice in the areas of visual anthropology, the documentary arts (film/photography/installation), media culture and media anthropology. Conceptual and practical knowledge within these areas can be applied in academia, the arts, and culture and media industries, as well as to social, applied, or educational media projects. Students study the theoretical and practical foundations of visual anthropology, they gain experience in film production, project development, and (audio-) visual installation. Ultimately, they acquire the necessary skills for producing their own research projects and media outputs. STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE 05 STRUCTURE AND PROGRAM OUTLINE > Structure The Master Program was designed with working professio- Students have the possibility to complete the program after nals in mind. The in-house classes will be offered as block 5 semesters (two and a half years). -

Anthropology 1

Anthropology 1 ANTHRO 221-0 Social and Health Inequalities (1 Unit) Bidirectional ANTHROPOLOGY relationship between social (e.g., class, gender, and racial/ethnic) and health inequalities, including institutional/structural, individual/family/ anthropology.northwestern.edu psychosocial, and biological mechanisms. Anthropology is the study of humankind from a broadly comparative and ANTHRO 232-0 Myth and Symbolism (1 Unit) Introduction to different historical perspective. Anthropology advances understanding of human approaches to the interpretation of myth and symbolism, e.g., Freudian, biological and cultural diversity around the world and across time. In a functionalist, and structuralist. Ethics Values Distro Area changing world, anthropology provides for cross-cultural comparative ANTHRO 235-0 Language in Asian America (1 Unit) Survey of linguistic analysis of diversities and inequalities. Understanding cultural, biological, anthropological topics relevant to Asian American communities, and linguistic differences and similarities is central to almost any career, including bilingualism, code switching, language socialization, language and students gain a critical understanding of ethical issues at play in a shift, style, sociolinguistic variation, indexicality, media, and semiotics. diverse, globalized world. ANTHRO 235-0 and ASIAN_AM 235-0 are taught together; may not receive credit for both courses. Social Behavioral Sciences Distro Area Anthropology draws on the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences to answer compelling -

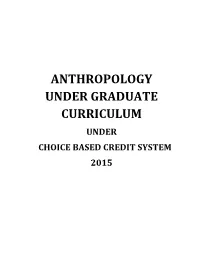

Anthropology Under Graduate Curriculum Under Choice Based Credit System 2015 Overview of Curriculum

ANTHROPOLOGY UNDER GRADUATE CURRICULUM UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM 2015 OVERVIEW OF CURRICULUM I. Core course Year Semester Paper No. Title of Paper I ANTH-101 Introduction to Biological Anthropology First ANTH-102 Introduction to Socio-cultural Anthropology II ANTH-201 Archaeological Anthropology ANTH-202 Fundamentals of Human Origin & Evolution III ANTH-301 Tribes and Peasants in India ANTH-302 Human Ecology: Biological & Cultural dimensions Second ANTH-303 Biological Diversity in Human Populations IV ANTH-401 Theories of Culture and Society ANTH-402 Human Growth and Development ANTH-403 Research Methods V ANTH-501 Human Population Genetics Third ANTH-502 Anthropology in Practice VI ANTH-601 Forensic Anthropology ANTH-602 Anthropology of India II. Elective Course A. Discipline Specific B. Generic Elective/Interdisciplinary Two each in Semester V and VI. To be chosen from the One each in Semester I, II, III and IV. To be following. chosen from the following. DSE-1: Physiological Anthropology GE-1: Health science DSE-2: Sports and Nutritional Anthropology GE-2: Home science DSE-3: Human Genetics GE-3: Biotechnology DSE-4: Neuro Anthropology GE-4: Psychology DSE-5: Forensic Dermatoglyphics GE-5: Animation and Visual Graphics DSE-6: Paleoanthropology GE-6: Interior Design DSE-7: Anthropology of Religion, Politics and economy GE-7: Economics DSE-8: Tribal Cultures of India GE-8: Environmental Science DSE-9: Indian Archaeology GE-9: Fashion Design DSE-10: Visual Anthropology GE-10: Food Technology DSE-11: Fashion Anthropology GE-11: Forestry DSE-12: Demographic Anthropology GE-12: Neuro Science DSE-13: Urban Anthropology GE-13: Physical Education DSE-14: Anthropology of Health GE-14: Tourism Administration DSE-15: Dissertation (in Semester VI only) GE-15: Insurance and Banking GE-16: Journalism and Mass Communication GE-17: BCA GE-18: BBA GE-19: Hotel Management GE-20: BBA (Health Care Management) GE-21: Marine Science III. -

Proposal Template

2018 | San José, California A Note from the Hammer Theater THE SVA PROGRAM IS HOSTED AT: Our goal at the Hammer Theater is for every person to enjoy an outstanding experi- ence. Please contact the Director of Patron Services, Maria Bones, (408) 924-8510, if SJSU Hammer Theatre Center 101 Paseo De San Antonio, there is anything we can do to serve you better. San Jose, CA 95113 HAMMER THEATER POLICIES All patrons, regardless of age, must have a ticket. CONDUCT: We reserve the right to refuse admission or eject any person whose conduct is deemed unbecoming or interferes with the audience’s ability to enjoy the performance in the manner in which it was intended, without a refund on their ticket purchase or exchange to another performance. PARCELS, BAGS: Theatre Management reserves the right to require you to open personal bags and knapsacks for inspection as a condition of entry to the theatre. We may require that some items not be allowed into the theatre for security reasons. EMERGENCIES: Please become familiar with the exits. In an emergency, listen for instructions. In the case of an earthquake, remain seated, or crouch below seats, then listen for instructions from the Hammer staf. All AAA Conference Panels and Roundtables are No smoking or vaping allowed. We are a smoke-free campus. taking place at the San Jose McEnery Conven- No outside food or drink allowed into the theatre. tion Center. Visit www.americananthro.org to We welcome Service Animals, but NO PETS please. Service Animals are those who have been register for the conference and get access to the specially trained to assist their owner with a disability.