NORTHERN IRELAND (STANDREWS AGREEMENT) ACT 2007* (2007 C.4)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGREEMENT at ST ANDREWS Over the Past Three Days in St Andrews

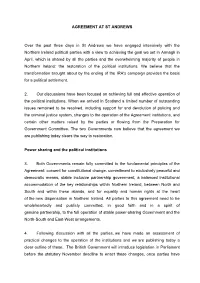

AGREEMENT AT ST ANDREWS Over the past three days in St Andrews we have engaged intensively with the Northern Ireland political parties with a view to achieving the goal we set in Armagh in April, which is shared by all the parties and the overwhelming majority of people in Northern Ireland: the restoration of the political institutions. We believe that the transformation brought about by the ending of the IRA's campaign provides the basis for a political settlement. 2. Our discussions have been focused on achieving full and effective operation of the political institutions. When we arrived in Scotland a limited number of outstanding issues remained to be resolved, including support for and devolution of policing and the criminal justice system, changes to the operation of the Agreement institutions, and certain other matters raised by the parties or flowing from the Preparation for Government Committee. The two Governments now believe that the agreement we are publishing today clears the way to restoration. Power sharing and the political institutions 3. Both Governments remain fully committed to the fundamental principles of the Agreement: consent for constitutional change, commitment to exclusively peaceful and democratic means, stable inclusive partnership government, a balanced institutional accommodation of the key relationships within Northern Ireland, between North and South and within these islands, and for equality and human rights at the heart of the new dispensation in Northern Ireland. All parties to this agreement need to be wholeheartedly and publicly committed, in good faith and in a spirit of genuine partnership, to the full operation of stable power-sharing Government and the North-South and East-West arrangements. -

Cooperation Programmes Under the European Territorial Cooperation Goal

Cooperation programmes under the European territorial cooperation goal CCI 2014TC16RFPC001 Title Ireland-United Kingdom (PEACE) Version 1.2 First year 2014 Last year 2020 Eligible from 01-Jan-2014 Eligible until 31-Dec-2023 EC decision number EC decision date MS amending decision number MS amending decision date MS amending decision entry into force date NUTS regions covered by IE011 - Border the cooperation UKN01 - Belfast programme UKN02 - Outer Belfast UKN03 - East of Northern Ireland UKN04 - North of Northern Ireland UKN05 - West and South of Northern Ireland EN EN 1. STRATEGY FOR THE COOPERATION PROGRAMME’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE UNION STRATEGY FOR SMART, SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH AND THE ACHIEVEMENT OF ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND TERRITORIAL COHESION 1.1 Strategy for the cooperation programme’s contribution to the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and to the achievement of economic, social and territorial cohesion 1.1.1 Description of the cooperation programme’s strategy for contributing to the delivery of the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and for achieving economic, social and territorial cohesion. Introduction The EU PEACE Programmes are distinctive initiatives of the European Union to support peace and reconciliation in the programme area. The first PEACE Programme was a direct result of the European Union's desire to make a positive response to the opportunities presented by developments in the Northern Ireland peace process during 1994, especially the announcements of the cessation of violence by the main republican and loyalist paramilitary organisations. The cessation came after 25 years of violent conflict during which over 3,500 were killed and 37,000 injured. -

The Good Friday Agreement – an Overview

The Good Friday Agreement – An Overview June 2013 2 The Good Friday Agreement – An Overview June 2013 June 2013 3 Published by Democratic Progress Institute 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] +44 (0)203 206 9939 First published, 2013 ISBN: 978-1-905592-ISBN © DPI – Democratic Progress Institute, 2013 DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable 4 The Good Friday Agreement – An Overview Abstract For decades, resolving the Northern Ireland conflict has been of primary concern for the conflicting parties within Northern Ireland, as well as for the British and Irish Governments. Adopted in 1998, the Good Friday Agreement has managed to curb hostilities, though sporadic violence still occurs and antagonism remains pervasive between many Nationalists and Unionists. Strong political bargaining through back-channel negotiations and facilitation from international and third-party interlocutors all contributed to what is today referred to as Northern Ireland’s peace process and the resulting Good Friday Agreement. Although the Northern Ireland peace process and the Good Friday Agreement are often touted as a model of conflict resolution for other intractable conflicts in the world, the implementation of the Agreement has proven to be challenging. -

Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is the author’s post-print version of an article published in Terrorism and Political Violence, 24 (1) White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/77668 Published article: Evans, JAJ and Tonge, J (2012) Menace Without Mandate? Is There Any Sympathy for “Dissident” Irish Republicanism in Northern Ireland? Terrorism and Political Violence, 24 (1). 61 - 78. ISSN 0954-6553 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2011.608818 White Rose Research Online [email protected] Menace without Mandate? Is there any sympathy for ‘dissident’ Irish Republicanism in Northern Ireland? Abstract Dissident Irish republicans have increased their violent activities in recent years. These diehard ‘spoilers’ reject the 1998 Good Friday Agreement power-sharing deal between unionist and nationalist traditions in Northern Ireland. Instead dissident IRAs vow to maintain an armed campaign against Britain’s sovereign claim to Northern Ireland and have killed British soldiers, police officers and civilians in recent years. These groups have small political organisations with which they are associated. The assumption across the political spectrum is that, whereas Sinn Fein enjoyed significant electoral backing when linked to the now vanished Provisional IRA, contemporary violent republican ultras and their political associates are utterly bereft of support. Drawing upon new data from the ESRC 2010 Northern Ireland election survey, the first academic study to ask the electorate its views of dissident republicans, this article examines whether there are any clusters of sympathy for these irreconcilables and their modus operandi. -

Stormont's Vetoes in the Context of a Pandemic – an Equality Coalition

STORMONT’S VETOES IN THE CONTEXT OF A PANDEMIC – AN EQUALITY COALITION BRIEFING NOTE COULD THE BILL OF RIGHTS HAVE CONSTRAINED THE USE OF THE ST ANDREWS VETO TO BLOCK AN EXTENSION TO PUBLIC HEALTH MEASURES TO CONTAIN COVID 19? SUMMARY ➢ In 2019, the Equality Coalition’s Manifesto for a Rights Based Return to Power Sharing called for a new agreement to remove those political vetoes within the NI Executive that are not based on (and have conflicted with) equality and rights duties, and as such contributed to the destabilisation and collapse of the NI Executive in 2017. ➢ The issue returned to prominence last week with the DUP twice using the ‘St Andrews Veto’ to block the extension of public health measures proposed by the UUP Health Minister to contain the pandemic, which were supported by all other parties. ➢ The ‘veto’ in question is not the ‘Petition of Concern’, which is a GFA safeguard regarding legislation and other measures in the NI Assembly. As originally set out in the GFA, the Petition of Concern was to be linked to equality requirements (specifically scrutiny against the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) and the NI Bill of Rights), but it has never been implemented as was intended. ➢ The recent veto used by the DUP was introduced after the 2006 St Andrews Agreement and relates to decisions made within the NI Executive (i.e. cabinet of Stormont Ministers). This veto was grounded in two significant changes, which were as follows: ▪ The veto changed how Executive decisions were taken by introducing a process where three ministers (without any criteria) can require a NI Executive decision to be taken on a ‘cross community basis’, rather than by a simple majority; ▪ The veto significantly extended which decisions need to be taken by the NI Executive as a whole rather than individual ministers. -

Sharing Lessons Between Peace Processes: a Comparative Case Study on the Northern Ireland and Korean Peace Processes

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Sharing Lessons between Peace Processes: A Comparative Case Study on the Northern Ireland and Korean Peace Processes Dong Jin Kim ID Irish School of Ecumenics, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; [email protected] Received: 9 February 2018; Accepted: 16 March 2018; Published: 20 March 2018 Abstract: In both Northern Ireland and Korea, the euphoria following significant breakthroughs towards peace in the late 1990s and early 2000s turned into deep frustration when confronted by continuous stalemates in implementing the agreements. I explore the two peace processes by examining and comparing the breakthroughs and breakdowns of both, in order to identify potential lessons that can be shared for a sustainable peace process. Using a comparative case study, I demonstrate the parallels in historical analyses of why the agreements in the late 1990s and early 2000s in Northern Ireland and Korea were expected to be more durable than those of the 1970s. I also examine the differences between the two peace processes in the course of addressing major challenges for sustaining the two processes: disarmament; relationships between hard-line parties; cross-community initiatives. These parallels and differences inform which lessons can be shared between Northern Ireland and Korea to increase the durability of the peace processes. The comparative case study finds that the commitment of high-level leadership in both conflict parties to keeping negotiation channels open for dialogue and to allowing space for civic engagement is crucial in a sustainable peace process, and that sharing lessons between the two peace processes can be beneficial in finding opportunities to overcome challenges and also for each process to be reminded of lessons from its own past experience. -

The Good Friday Agreement As a Framework

THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT AS A FRAMEWORK: THE FUTURE OF PEACE IN NORTHERN IRELAND by Heather McAdams A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Bachelor of Arts in International Relations with Distinction Spring 2017 © 2017 Heather McAdams All Rights Reserved THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT AS A FRAMEWORK: THE FUTURE OF PEACE IN NORTHERN IRELAND by Heather McAdams Approved: __________________________________________________________ John Patrick Montaño, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Political Science & International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ Theodore Davis, Ph.D. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: __________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people I would like to thank, from my parents and friends— my mother patiently supported me as I spent spring break panicking over submitting my thesis proposal—to my academic mentors—thanks to them, that proposal panic was the first and only thesis-related panic I experienced. First, I would like to specifically thank Professor Montaño, who graciously accepted the position of Thesis Committee Chair for an international relations student who simply wanted to write about the Good Friday Agreement. He not only helped me write an effective thesis section-by-section, but supplied an encouraging and calming voice throughout the process. I also would like to thank Professor Kaufman, my committee member from my department, and Professor Davis, my committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers. -

St-Andrews-Agreement.Pdf

AGREEMENT AT ST ANDREWS Over the past three days in St Andrews we have engaged intensively with the Northern Ireland political parties with a view to achieving the goal we set in Armagh in April, which is shared by all the parties and the overwhelming majority of people in Northern Ireland: the restoration of the political institutions. We believe that the transformation brought about by the ending of the IRA's campaign provides the basis for a political settlement. 2. Our discussions have been focused on achieving full and effective operation of the political institutions. When we arrived in Scotland a limited number of outstanding issues remained to be resolved, including support for and devolution of policing and the criminal justice system, changes to the operation of the Agreement institutions, and certain other matters raised by the parties or flowing from the Preparation for Government Committee. The two Governments now believe that the agreement we are publishing today clears the way to restoration. Power sharing and the political institutions 3. Both Governments remain fully committed to the fundamental principles of the Agreement: consent for constitutional change, commitment to exclusively peaceful and democratic means, stable inclusive partnership government, a balanced institutional accommodation of the key relationships within Northern Ireland, between North and South and within these islands, and for equality and human rights at the heart of the new dispensation in Northern Ireland. All parties to this agreement need to be wholeheartedly and publicly committed, in good faith and in a spirit of genuine partnership, to the full operation of stable power-sharing Government and the North-South and East-West arrangements. -

Professor Rick Wilford Paper

Hi I've been away on & off so too little time available to furnish a response to the Bill. Had I more notice I could have done something. Instead, perhaps the Committee might take a look at my article in the current issue of Parliamentary Affairs, 'Two Cheers for Consociational Democracy.....' Its focus is on Assembly & Executive reform. Rick Wilford Parliamentary Affairs (2015) 68, 757–774 doi:10.1093/pa/gsu024 Advance Access Publication 11 November 2014 Two Cheers for Consociational Democracy? Reforming the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive Downloaded from Rick Wilford* School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University, 25 University Square, Belfast BT7 1PB, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] http://pa.oxfordjournals.org/ This article discusses the attempts to reform the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive by the former’s Assembly and Executive Review Committee. It situates the Committee’sreview of the Belfast Agreement’sStrand One institutions within the context both of prior proposals to effect reform and the constraints, institu- tional and behavioural, created by Northern Ireland’s model of consociational democracy. at Northern Ireland Assembly on November 5, 2015 1. Introduction In his 1938 essay, ‘What I Believe’, E M Forster voiced ‘two cheers for democracy: one, because it admits variety and two, because it permits criticism’ (Forster, 1972). ‘Variety’ or, to adopt the consociational lexicon, ‘inclusiveness’,is a corner- stone of devolved institutional design in Northern Ireland (NI), and the compos- ition of the Assembly and Executive Review Committee (AERC) tasked to review the potential for reform of the Strand One institutions—the subject of this paper—meets that test (see below). -

Governed by Guerrillas: When Armed Insurgents Become Political Leaders

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2017 Governed by Guerrillas: When Armed Insurgents Become Political Leaders Megan Patsch Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Patsch, Megan, "Governed by Guerrillas: When Armed Insurgents Become Political Leaders" (2017). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1813. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1813 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOVERNED BY GUERRILLAS: WHEN ARMED INSURGENTS BECOME POLITICAL LEADERS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By MEGAN PATSCH B.A. Political Science, Marietta College, 2011 2017 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL 7/28/2017 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Megan Patsch ENTITLED Governed by Guerrillas: When Armed Insurgents Become Political Leaders BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ______________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. Thesis Director ______________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. Department of Political Science ___________________________________ December Green, Ph. D. Department of Political Science ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Department of Political Science ______________________________ Robert E. -

Northern Ireland: the Peace Process, Ongoing Challenges, and U.S. Interests

Northern Ireland: The Peace Process, Ongoing Challenges, and U.S. Interests Updated September 10, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46259 SUMMARY R46259 Northern Ireland: The Peace Process, Ongoing September 10, 2021 Challenges, and U.S. Interests Kristin Archick Between 1969 and 1999, roughly 3,500 people died as a result of political violence in Northern Specialist in European Ireland, which is one of four component “nations” of the United Kingdom (UK). The conflict, Affairs often referred to as “the Troubles,” has its origins in the 1921 division of Ireland and has reflected a struggle between different national, cultural, and religious identities. Protestants in Northern Ireland largely define themselves as British and support remaining part of the UK (unionists). Most Catholics in Northern Ireland consider themselves Irish, and many desire a united Ireland (nationalists). Successive U.S. Administrations and many Members of Congress have actively supported the Northern Ireland peace process. For decades, the United States has provided development aid through the International Fund for Ireland (IFI). In recent years, congressional hearings have focused on the peace process, police reforms, human rights, and addressing Northern Ireland’s legacy of violence (often termed dealing with the past). Some Members also are concerned about how Brexit—the UK’s withdrawal as a member of the European Union (EU) in January 2020—is affecting Northern Ireland. The Peace Agreement: Progress to Date and Ongoing Challenges In 1998, the UK and Irish governments and key Northern Ireland political parties reached a negotiated political settlement. The resulting Good Friday Agreement, or Belfast Agreement, recognized that a change in Northern Ireland’s constitutional status as part of the UK can come about only with the consent of a majority of the people in Northern Ireland (as well as with the consent of a majority in Ireland). -

British-Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body Was Established in February 1990 with the Consent and Co-Operation of Both Governments

EUR(3)-06-10(p.2) European and External Affairs Committee Date: Tuesday 8 June 2010 Venue: Committee Room 1, Senedd Title: Update on Assembly Members’ activities: British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA) PURPOSE 1. To update the Committee on the work of the British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA). BACKGROUND 2. At the request of Members of the Oireachtas in Dublin and the Parliament at Westminster, the British-Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body was established in February 1990 with the consent and co-operation of both Governments. 3. Initially, the Body provided a link between the UK and Irish Sovereign Parliaments, though since 2001 it went through a post devolution enlargement exercise incorporating the Scottish Parliament, the devolved assemblies and the Crown dependencies within its structure. 4. In October 2008, the British-Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body, re-branded itself as the British Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA). During this period the remaining places on the BIPA which were available to members of the Northern Ireland Assembly, were filled by the Democratic Unionist Party and Ulster Unionist Party. 5. The purpose of the BIPA is to bring together Members of the participating institutions to engage jointly in a wide range of non- legislative parliamentary activities. The Rules for the Conduct of Business are relatively brief and based on the practice of the House of Commons and the Dáil Èireann. 6. The BIPA consists of: a. Twenty-five Members from each sovereign Parliament (Irish Members & British Members). b. Five each from the Scottish Parliament, the Northern Ireland Assembly and the National Assembly for Wales. c.