A Preliminary Density Estimate for Andean Bear Using Camera-Trapping Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution, Natural History and Conservation Status of Two

Bird Conservation International (2008) 18:331–348. ª BirdLife International 2008 doi:10.1017/S0959270908007491 Printed in the United Kingdom Distribution, natural history and conservation status of two endemics of the Bolivian Yungas, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, A. BENNETT HENNESSEY, MICHAEL KESSLER and VI´CTOR H. GARCI´A-SOLI´Z Summary Since their description in the first half of the 20th century by M. A. Carriker, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea have been regarded as extremely poorly known endemics of the Bolivian Yungas and adjacent humid foothill forests. They are considered ‘Vulnerable’ under the IUCN criteria of small population, predicted population decline (criterion C2a) and, in the case of Bolivian Recurvebill, small extent of occurrence (criteria B1a+b). Here we summarise the information published to date and present extensive new data on the distribution (including the first records for extreme southeast Peru), natural history, population size and conservation status of both species based on field work in the Bolivian Andes over the past 12 years. Both species primarily inhabit the understorey of primary and mid-aged to older regenerating forest and regularly join mixed-species foraging flocks of insectivorous birds. Bolivian Recurvebill has a strong preference for Guadua bamboo, but it is not an obligate bamboo specialist and persists at often much lower densities in forests without Guadua. Yungas Antwren seems to have a preference for dense, structurally complex under- storey, often with Chusquea bamboo. Both species are distributed much more continuously at altitudes of mostly 600–1,500 m, occupy a greater variety of forest types (wet, humid, semi- deciduous forest) and have a much greater population size than previously thought. -

Critical Population Status of the Jaguar Panthera Onca in the Argentine Chaco: Camera-Trap Surveys Suggest Recent Collapse and Imminent Regional Extinction

Critical population status of the jaguar Panthera onca in the Argentine Chaco: camera-trap surveys suggest recent collapse and imminent regional extinction V ERÓNICA A NDREA Q UIROGA,GABRIEL I VÁN B OAGLIO,ANDREW J AY N OSS and M ARIO S ANTIAGO D I B ITETTI Abstract The population of jaguars Panthera onca in Keywords Argentina, Chaco, conservation, distribution, the semi-arid Chaco Province is the least well-known in interview, monitoring, Panthera onca, presence Argentina. Its status in the region is described only from interviews that confirmed its presence until 2003. To update information on the distribution and population density Introduction of this species we undertook three camera-trap surveys, combined with searches for sign, at sites across latitudinal he distribution of the jaguar Panthera onca in and protection gradients, and 156 interviews with local TArgentina has declined by . 90% and , 200 individ- inhabitants across three larger areas. The camera-trap sites uals survive in three isolated regions: the Atlantic Forest, were located in areas with the highest density of records in the Yungas and the Chaco forest (Di Bitetti et al., in press). the Argentine Chaco: Copo National Park (1,204 trap days, The jaguar is a National Natural Monument protected by 24 stations, 344 km of transects), Aborigen Reserve (1,993 national and provincial laws, although these are rarely trap days, 30 stations, 251 km of transects) and El Cantor enforced. The most recent national categorization based on (2,129 trap days, 35 stations, 297 km of transects). We did not IUCN criteria considers the species Critically Endangered in obtain any photographs of jaguars. -

(CARNIVORA, URSIDAE) F. Brandstaetter the Andean Bear

Zoodiversity, 54(5): 357–362, 2020 DOI 10.15407/zoo2020.05.357 UDC 599.742.2:57.06(238.13) A CONTRIBUTION TO THE TAXONOMY OF THE ANDEAN BEAR, TREMARCTOS ORNATUS (CARNIVORA, URSIDAE) F. Brandstaetter Zoo Dortmund, 44225 Dortmund, Germany E-mail: [email protected] F. Brandstaetter (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7493-8526) A Contribution to the Taxonomy of the Andean Bear, Tremarctos ornatus (Carnivora, Ursidae). Brandstaetter, F. — The Andean bear’s taxonomy is discussed with some nomenclatorial corrections and discussions of some common names for the species. The most widely used common name has been changed from spectacled bear to Andean bear in favour of the animal’s importance in conservation issues for the Andean region. Key words: Andean bear, taxonomy, nomenclature, Tremarctos ornatus, conservation. The Andean bear, Tremarctos ornatus (Cuvier, 1825), is an enigmatic species of the Andes. It has even been declared an umbrella species for the conservation of the whole Andean ecosystem (Troya et al., 2004; Ruiz-Garcia et al., 2005). Being the only true bear species in South America the Andean bear is unique in its perception and as a representative of the South American fauna. As Morrison III et al. (2009) and Kitchener (2010) have pointed out, taxonomy is fundamental to conservation. Scientific names are the device to clearly determine a species (Ng, 1994). All communication about animals, biodiversity and conservation is based on the stability and exactness of scientific names and the whole community is responsible for a proper use (Welter-Schultes, 2013). With regard to this, the taxonomy of the Andean bear is analyzed in the following. -

References: Future Works

Phylogenomics and Evolution of the Ursidae Family Department of Biology Ammary Jackson, Keanu Spencer, & Alissya Theis Fig 8. Red Panda Fig. 6. American Black Bear (Ailurus fulgens) (Ursus americanus) Introduction: Ursidae is a family of generally omnivorous mammals colloquially Objectives: Results: referred to as bears. The family consists of five genera: Ailuropoda ● To determine the relatedness among the 30 individual bear taxa. Red Panda (giant panda), Helarctos (sun bear), Melursus (sloth bear), Tremarctos Spectacled Bear ● To determine if Ailurus fulgens obtained its common Spectacled Bear (spectacled bear), and Ursus (black, brown, and polar bears) all of Polar Bear name (Red Panda) from similarities to the genes Polar Bear which are found in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa Polar Bear belonging to the Ursidae family or if it’s simply based on Polar Bear (Kumar et al. 2017.) The phylogenetic relationship between Ursidae Polar Bear phenotypic attributes. Polar Bear bears and the red panda (Ailurus fulgens) has been somewhat Brown Bear inconsistent and controversial. Previous phylogenetic analyses have Brown Bear Brown Bear placed the red panda within the families Ursidae (bears), Procyonidae Polar Bear Brown Bear (raccoons), Pinnepedia (seals), and Musteloidea (raccoons and weasels, Brown Bear Brown Bear skunks, and badgers) (Flynn et al. 2000.) Determining monophyly Methods: Cave Bear Cave Bear would elucidate the evolutionary relationship between Ursidae bears Sloth Bear ● Mitochondrial gene sequences of the ATP6 and ND1 genes Sloth Bear and the Red Panda. This analysis (i) tested the monophyly of the family Sun Bear were taken from a sample of 31 species (30 Ursidae family Sun Bear Ursidae; and (ii) determined how the Red Panda fits within the Black Bear and 1 Ailuridae family). -

EAZA Position Statement on Bears in Commercial Entertainment

EAZA Position Statement on Bears in Commercial Entertainment • The EAZA Bear Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) members are recognised experts on the husbandry and welfare of bears that are held under human care. • EAZA members abide by codes and standards, most notably the ‘EAZA Code of Ethics’ and the ‘EAZA Minimum Standards for the Accommodation and Care of Animals in Zoos and Aquaria’. Additionally, for the housing and care of bear species EAZA members follow the EAZA Husbandry Guidelines for bears. • EAZA and its Bear TAG do not support any use of bears for reasons of purely commercial entertainment, especially when such use involves the manipulation or removal of the bear from its normal social group or enclosure. The European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) represents 340 members from 41 countries, of which more than 280 are located in the European Union. EAZA collections house more than 250,000 animals, excluding fish and invertebrates. Under the umbrella of the EAZA Bear TAG, EAZA runs conservation breeding programmes for six bear species, namely: European brown bear, polar bear, Asiatic black bear, sloth bear, Malayan sun bear and spectacled bear. In this context we wish to present our position on the use of bears purely for commercial entertainment. Bears held under human care in zoological gardens fulfil an ambassadorial role for their wild living conspecifics as well as highlighting the plight of bears that are illegally traded and used, and often misused, for purely commercial entertainment purposes. Bears held in EAZA zoos are of importance for getting a (bear) conservation education message across to the general public. -

Monitoring Ecosystems and Biodiversity at a Continental Scale—A Proposal for South America

Monitoring Ecosystems and Biodiversity at a Continental Scale—A Proposal for South America Dr. Xavier Silva, Director, IDB-TNC Ecoregional Project, South America. Teacher and Lecturer, San Francisco de Quito University. Board Member, OÏKOS Foundation Abstract—A monitoring system plan is being developed in South America to assess critically endangered ecoregions. The system will be based on a previous ecosystem and biodiversity inventory developed through a large gap analysis program in five South American ecoregions. The monitoring system will include three main elements: (1) Landscape Ecology: vegetation cover, fragmentation and deforestation, infrastruc- ture (road, dams, pipelines); (2) Biological guidelines: species richness, endemism, endangered species and species of a particular interest; and (3) Conservation Policy and Socio-Economic guidelines: national protected areas systems, conservation policies, human population on important areas, main economic activities and other. Such a sys- tem is an important need for governments and private organizations in South America, especially to detect critical sites and socio-political issues before the environmental problems become too large. Introduction and Background Among the results, 6,473 species of flora and fauna have been analyzed (each one with a map indicating it’s Environmental surveillance at a continental scale is potential geographic distribution), and over 6,500 the- an important conservation requirement in vast territo- matic maps have been produced, indicating vegetation ries, such as in South America, where large and diverse types, centers of high diversity and endemism, current ecoregions are being altered by a number of unsustainable and potential threats, forest fragmentation, infrastructure, location of protected areas, and basic socio-economical development practices (Busch and Trexler 2003, World information. -

Changing Patron-Client Reiationships in the Bolivian Yungas

LTC Reprint No. 101 August 1973 U.S. ISSN 0084-0807 New Patrons for Old: Changing Patron-Client Reiationships in the Bolivian Yungas by Dwight B. Heath LAND TENURE CENTER University of Wisconsin-Madison 53706 Reprinted from Volume XI, No. 1, Jamuary, 1973 New Patrons For Old: Changing Patron-Client Relationships in the Bolivian Yungast Dwight B.Heath Brown University la are proud ben- campesinos of the yungas region of BL, The Aymara century South America. of the first social revolution in twentieth eficiaries 2 that brought the Nationalist Although they took no oart v, the fighting to power in 1052, they are still militant Revolutionary Movemenit (MNR) of the party that they say "gave [them] the conquests in support of tlat nationalization of namely: agrarian reform, universal suffrage, revolution, ' the most telling indication of mines, and educational reform." Perhaps the of the traditional quasi-feudal the quality of change since the overthrow which camrpesinos assert that "now system is the depth o,feeling with human beings!"' we are becoming or "victims" -to those affect!d--either as beneficiaries It is difficult for a revolu the pervasiveness of change in such do other than overestimate tht social scicntist who never suffered tionary setting. Neveitheless, a. a nor the anguish and discomfort of losing pain and humiliation of serfdom, in marked continuity in terms of firnctions, land and laboiers, I discern of when analyzing what has become spite of appreLiable formal change, in the yungas region of Bolivia. patronage, clientage, and power structures THE Sf'rnwr, in Bolivia, th, and immensely varied ecological niches Among the many uniiersal that their Aymara name has come into yungas are !o distinctive eastern of rugged montane iungle in the usage. -

Biodiversity Conservation at the Landscape Scale a Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society Supported by the USAID/Global Conservation Program

Biodiversity Conservation at the Landscape Scale A Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society Supported by the USAID/Global Conservation Program Greater Madidi Landscape Conservation Area Implementation Plan October 2006 – September 2007 Living Landscapes Program- Bolivia/Madidi Wildlife Conservation Society 30 September 2006 USAID EGAT/NRM/Biodiversity Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement Award LAG-A-00-99-00047-00 Biodiversity Conservation at the Landscape Scale A Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society Supported by the USAID/EGAT Global Conservation Program Greater Madidi Landscape Conservation Area Implementation Plan FY2007 October 2006 – September 2007 Program Goal To ensure conservation of biological diversity in regions of global biodiversity importance, using a species-based landscape approach. The Wildlife Conservation Society believes that protected areas must remain at the core of all nations’ biodiversity conservation plans. These areas typically contain a higher diversity and abundance of plants and animals than landscapes managed primarily for economic use. Yet, parks and reserves are always embedded in larger, human-dominated landscapes and are seldom sacrosanct. Regardless of how large or small a protected area may be, the plants and animals it contains are often threatened either directly or indirectly by human resource use activities. Management of parks and reserves cannot, therefore, occur in isolation from the surrounding human-dominated landscape, but must take into account where and how human activities conflict with biodiversity conservation, and where conservation adversely impacts human welfare. As human populations continue to expand over the next 50 years, the incentive for over- exploiting natural resources within and outside of protected areas will likely increase and the need for biodiversity conservation tools that address human-wildlife conflict will become even more important. -

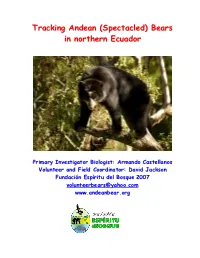

Tracking Andean (Spectacled) Bears in Northern Ecuado Rr

Tracking Andean (Spectacled) Bears in northern Ecuador Primary Investigator Biologist: Armando Castellanos Volunteer and Field Coordinator: David Jackson Fundación Espíritu del Bosque 2007 [email protected] www.andeanbear.org USE OF HABITAT AND PATTERNS OF ACTIVITY OF ANDEAN (SPECTACLED) BEARS IN NORTHERN ECUADOR. PROJECT SUMMARY This is the only project in the world that radio tracks Andean Bears (Tremarctos ornatus) in the wild. The resea rch is part of ongoing work to save the Andean Bear and is led by ecologist and bear expert Armando Castellanos. The project is based in the Intag Region of Northern Ecuador. The purpose of the current research is to learn about ecology of the wild Andean bear. The information learned about the bears in this research will help protect and conserve the bears’ habitats and improve future rehabilitation projects both here in Ecuador and throughout South America. This research is being conducted using dire ct methods. Twelve wild bears (six females and six males) have been collared with radio telemetry devices, and we expect to catch five more. We measure the actual location and activity of each bear by listening to the signals from the collars. THE ANDEAN (SPECTACLED) BEAR Most people do not know that the elusive Andean Bear, known for the white or brown marking around the eyes, lives in the Ecuadorian Andes. It the only species of South American bear, found in a narrow strip running from western Venezuela through the Andes in Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and ending in Northern Argentina. It is an “Endangered” species in Ecuador, mostly due to habitat fragmentation caused by livestock farming and logging. -

RBB01600 Ot Vioborgesmaia

MANED WOLVES IN CAPTIVITY 25 BIRTH AND MORTALITY OF MANED WOLVES Chrysocyon brachyurus (ILLIGER, 1811) IN CAPTIVITY MAIA, O. B.1 and GOUVEIA, A. M. G.2 1Consultor do Plano de Manejo do Lobo-guará 2Escola de Veterinária da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Correspondence to: Otávio Borges Maia, Laboratório de Virologia Animal, Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, C.P. 567, CEP 30123-970, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, e-mail: [email protected] Received January 25, 2000 – Accepted July 17, 2000 – Distributed February 28, 2002 (With 5 figures) ABSTRACT The aims of this study were to verify the distribution of births of captive maned wolves Chrysocyon brachyurus and the causes of their deaths during the period from 1980 to 1998, based on the reg- istry of births and deaths in the International Studbook for Maned Wolves. To determine birth dis- tribution and average litter size, 361 parturitions were analyzed for the 1989-98 period. To analyze causes of mortality, the animals were divided into four groups: 1. pups born in captivity that died prior to one year of age; 2. animals born in captivity that died at more than one year of age; 3. ani- mals captured in the wild that died at any age; and 4. all animals that died during the 1980-98 pe- riod. In group 1, the main causes of mortality were parental incompetence (67%), infectious diseases, (9%) and digestive system disorders (5%). The average mortality rate for pups was 56%. Parental in- competence was responsible for 95% of pup deaths during the first week of life. -

Procyonid (Procyonidae) Care Manual

PROCYONID (Procyonidae) CARE MANUAL CREATED BY THE AZA Small Carnivore Taxon Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AZA Animal Welfare Committee Procyonid (Procyonidae) Care Manual Procyonid (Procyonidae) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Small Carnivore TAG 2010. Procyonid (Procyonidae) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. p.114. Original Completion Date: 13 August 2008, 1st revision June 2009, 2nd revision May 2010 Authors and Significant contributors: Jan Reed-Smith, M.A., Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Celeste (Dusty) Lombardi, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, AZA Small Carnivore TAG (SCTAG) Chair Mike Maslanka, M.S., Smithsonian‟s National Zoo, AZA Nutrition SAG Barbara Henry, M.S., Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden, AZA Nutrition SAG Chair Miles Roberts, Smithsonian‟s National Zoo Kim Schilling, Animals for Awareness Anneke Moresco, D.V.M., Ph.D., UC Davis, University of California See Appendix L for additional contributors to the Procyonid Care Manual. AZA Staff Editors: Lacey Byrnes, B.S. ACM Intern Candice Dorsey, Ph.D., Director of Animal Conservation Cover Photo Credits: Liz Toth Debbie Thompson Cindy Colling Reviewers: Sue Booth-Binczik, Ph.D., Dallas Zoo Denise Bressler, Logan & Abby‟s Fund Kristofer Helgen, Smithsonian Institution Kim Schilling, Animals for Awareness Mindy Stinner, Conservators‟ Center, Inc. Debbie Thompson, Little Rock Zoo Rhonda Votino Debborah Colbert Ph.D., AZA, Vice President of Animal Conservation Paul Boyle Ph.D., AZA, Senior Vice President of Conservation and Education Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

First Ornithological Inventory and Conservation Assessment for the Yungas Forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia

Bird Conservation International (2005) 15:361–382. BirdLife International 2005 doi:10.1017/S095927090500064X Printed in the United Kingdom First ornithological inventory and conservation assessment for the yungas forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia ROSS MACLEOD, STEVEN K. EWING, SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, ROSALIND BRYCE, KARL L. EVANS and AIDAN MACCORMICK Summary Bolivia holds one of the world’s richest avifaunas, but large areas remain biologically unexplored or unsurveyed. This study carried out the first ornithological inventory of one of the largest of these unexplored areas, the yungas forests of Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes. A total of 339 bird species were recorded including 23 restricted-range, four Near-Threatened, two globally threatened, one new to Bolivia and one that may be new to science. The study extended the known altitudinal ranges of 62 species, 23 by at least 500 m, which represents a substantial increase in our knowledge of species distributions in the yungas, and illustrates how little is known about Bolivia’s avifauna. Species characteristic of, or unique to, three Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs) were found. The Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes are a stronghold for yungas endemics and hold large areas of pristine Bolivian and Peruvian Upper and Lower Yungas habi- tat (EBAs 54 and 55). Human encroachment is starting to threaten the area and priority conser- vation actions, including designation as a protected area and designation as one of Bolivia’s first Important Bird Areas, are recommended. Introduction Bolivia holds the richest avifauna of any landlocked country. With a total of 1,398 species (Hennessey et al.