Fearnside, PM 1986. Spatial Concentration of Deforestation in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estradeiro BR-242/364 Movimento Pró-Logística/Aprosoja

Estradeiro BR-242/364 Movimento Pró-Logística/Aprosoja Lucélia Denise Avi Analista de Meio Ambiente e Infraestrutura e Logística Famato O Estradeiro Pelo terceiro ano consecutivo, a Aprosoja realiza estradeiros pelas principais vias de escoamento da produção agrícola do Estado, com o intuito de conferir in loco o andamento das obras e as condições das rodovias percorridas. Este programa é realizado em parceria com o Movimento Pró-Logística e as entidades que o compõe. Estradeiro BR-242 e BR-364 A primeira etapa do Estradeiro do ano de 2012 teve início entre os dias 01 e 05 de abril, percorrendo 2.261 km pelas BRs 242 e 364 nos estados de Mato Grosso e Rondônia. Primeiro dia: Cuiabá a Primavera do Leste Segundo dia: Primavera do Leste a Sorriso Terceiro dia: Sorriso a Vilhena Quarto dia: Vilhena a Porto Velho Quinto dia: Retorno Foram realizados simpósios sobre Logística do Brasil em Sorriso, Campo Novo do Parecis e Vilhena. Participantes do Estradeiro BR-242 e BR-364 Aprosoja: Daniel Sebben, Antonio Galvan, Albino Galvan, Tielli Bairros e José Rezende Movimento Pró-Logística: Edeon Vaz Famato: Lucélia Avi, Rogério Romanini, Rui Faria e José Guarino Sindicato Rural: Leonildo Barei Jornalista do G1: Leonardo Nascimento Estado de Rondônia: Nadir Comiran Mapa BR-242 e BR-364 Estradeiro BR-242 e BR-364 Primeiro dia (01/04): Saída de Cuiabá às 15h percorrendo as seguintes rodovias: BR-251/MT-020 – Cuiabá a Chapada dos Guimarães (61,4 km) BR-252/ MT-403 – Chapada dos Guimarães a Campo Verde (75,5 km) BR-070 – Campo Verde a Primavera do Leste (102,7 km) Todas as rodovias com asfalto em boas condições. -

Divisão Territorial De Cuiabá

WILSON PEREIRA DOS SANTOS Prefeito Municipal de Cuiabá JACY RIBEIRO DE PROENÇA Vice Prefeita Municipal ANDELSON GIL DO AMARAL PEDRO PINTO DE OLIVEIRA ÉDEN CAPISTRANO PINTO JOÃO DE SOUZA VIEIRA FILHO Secretário Municipal de Governo Secretário Municipal de Secretário Municipal de Meio Secretário Municipal de Trabalho, Comunicação Ambiente e Desenvolvimento Urbano Desenv. Econômico e Turismo. JOSÉ ANTÔNIO ROSA GUILHERME FREDERICO MÜLLER OSCAR SOARES MARTINS ADRIANA BUSSIKI SANTOS Procurador Geral do Município Secretário Municipal de Secretário Municipal de Trânsito e Presidente do Instituto de Pesquisa Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. Transporte Urbano e Desenvolvimento Urbano MÁRIO OLÍMPIO MEDEIROS FILHO GUILHERME ANTÔNIO MALUF PEDRO LUIZ SHINOHARA JÚLIO CÉSAR PINHEIRO Secretário Municipal de Cultura Secretária Municipal de Saúde Secretário Municipal de Esporte e Presidente da Agência Municipal de Cidadania Habitação Popular CELCITA ROSA PINHEIRO DA SILVA JOSÉ CARLOS CARVALHO SOUZA EDUARDO ALEXANDRE RICCI RONALDO ROSA TAVEIRA Secretário Municipal de Assistência Secretário Municipal de Finanças Ouvidor Geral do Município de Presidente do Instituto de Prev. Social e Desenvolvimento Humano Cuiabá/Ombudsman Social dos Serv. de Cuiabá JOSÉ EUCLIDES DOS SANTOS FILHO CARLOS CARLÃO P. DO NASCIMENTO LUIZ MÁRIO DE BARROS JOSÉ ANTÔNIO ROSA Secretário Municipal de Infra- Secretário Municipal de Educação Auditoria e Controle Interno Diretor Presidente da Agência Estrutura Municipal de Saneamento PREFEITURA MUNICIPAL DE CUIABÁ INSTITUTO DE PLANEJAMENTO E DESENVOLVIMENTO URBANO DIRETORIA DE PESQUISA E INFORMAÇÃO ORGANIZAÇÃO GEOPOLÍTICA DE CUIABÁ • LIMITES MUNICIPAIS • LIMITES DOS DISTRITOS • LIMITE DO PERÍMETRO URBANO • ADMINISTRAÇÕES REGIONAIS • ABAIRRAMENTO Cuiabá, agosto de 2007. 2007. Prefeitura Municipal de Cuiabá/IPDU Ficha catalográfica CUIABÁ. Prefeitura Municipal de Cuiabá / Organização Geopolítica de Cuiabá. -

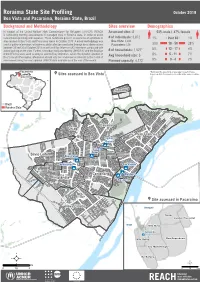

Roraima State Site Profiling. Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State

Roraima State Site Profiling October 2018 Boa Vista and Pacaraima, Roraima State, Brazil Background and Methodology Sites overview Demographics In support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), REACH Assessed sites: 8 53% male / 47% female 1+28+4+7+7 is conducting monthly assessments in managed sites in Roraima state, in order to assist 1+30+5+8+9 humanitarian planning and response. These factsheets present an overview of conditions in # of individuals: 3,872 1% 0ver 60 1% sites located in Boa Vista and Pacaraima towns in October 2018. A mixed methodology was Boa Vista: 3,444 used to gather information, with primary data collection conducted through direct observations Pacaraima: 428 30% 18 - 59 28% between 29 and 30 of October 2018 as well as 8 Key Informant (KI) interviews conducted with 5% 12 - 17 4% actors working on the sites. Further, secondary data provided by UNHCR KI and the Brazilian # of households: 1,527* Armed Forces were used to analyse selected key indicators. Given the dynamic situation in Avg household size: 3 8% 5 - 11 7% Boa Vista and Pacaraima, information should only be considered as relevant to the month of assessment using the most updated UNHCR data available as of the end of the month. Planned capacity: 4,172 9% 0 - 4 7% !(Pacaraima *Estimated by assuming an average household size, !( ¥Sites assessed in Boa Vista based on data from previous rounds in the same location. Boa Vista Cauamé Brazil Roraima State Cauamé União São Francisco Jardim Floresta ÔÆ Tancredo Neves Silvio Leite Nova Canaã ÔÆ ÔÆ Pintolândia São Vicente ÔÆ ÔÆ ÔÆ Centenário ÔÆ Rondon 1 Pintolândia Rondon 3 ¥Site assessed in Pacaraima Nova Cidade Venezuela Suapi Jardim Florestal Brazil Vila Nova Janokoida ÔÆ Das Orquídeas Vila Velha Ilzo Montenegro Da Balança ² ² km m 0 1,5 3 0 500 1.000 Fundo de População das Nações Unidas União Europeia Roraima site profiling October 2018 Jardim Floresta Boa Vista, Roraima State, Brazil Lat. -

Road Impact on Habitat Loss Br-364 Highway in Brazil

ROAD IMPACT ON HABITAT LOSS BR-364 HIGHWAY IN BRAZIL 2004 to 2011 ROAD IMPACT ON HABITAT LOSS BR-364 HIGHWAY IN BRAZIL 2004 to 2011 March 2012 Content Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Area of Study ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Habitat Change Monitoring ........................................................................................................................ 8 Previous studies ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Terra-i Monitoring in Brazil ..................................................................................................................... 9 Road Impact .......................................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Areas ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Carbon Stocks and Biodiversity ............................................................................................................. 17 Future Habitat Change Scenarios ............................................................................................................ -

Evolution of Land Use in the Brazilian Amazon: from Frontier Expansion to Market Chain Dynamics

Land 2014, 3, 981-1014; doi:10.3390/land3030981 OPEN ACCESS land ISSN 2073-445X www.mdpi.com/journal/land/ Article Evolution of Land Use in the Brazilian Amazon: From Frontier Expansion to Market Chain Dynamics Luciana S. Soler 1,2,*, Peter H. Verburg 3 and Diógenes S. Alves 4 1 Land Dynamics Group, Wageningen University, PO Box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands 2 National Early Warning and Monitoring Centre of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), Parque Tecnológico, Av. Dr. Altino Bondensan 500, São José dos Campos 12247, Brazil 3 Institute for Environmental Studies, VU University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1087, Amsterdam 1081 HV, The Netherlands; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Image Processing Division, National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Av. dos Astronautas 1758, São José dos Campos 12227, Brazil; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-12-3186-9236. Received: 31 December 2013; in revised form: 30 July 2014 / Accepted: 7 August 2014 / Published: 19 August 2014 Abstract: Agricultural census data and fieldwork observations are used to analyze changes in land cover/use intensity across Rondônia and Mato Grosso states along the agricultural frontier in the Brazilian Amazon. Results show that the development of land use is strongly related to land distribution structure. While large farms have increased their share of annual and perennial crops, small and medium size farms have strongly contributed to the development of beef and milk market chains in both Rondônia and Mato Grosso. Land use intensification has occurred in the form of increased use of machinery, labor in agriculture and stocking rates of cattle herds. -

Yellow Fever Epidemiological Update

Epidemiological Update Yellow Fever 10 July 2017 Situation summary in the Americas From epidemiological week (EW) 1 to EW 26 of 2017, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and Suriname have reported suspected and confirmed yellow fever cases. The following is an update on the situation in Brazil, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru. No changes in the number of reported cases have been reported in the other countries. In Brazil, since the beginning of the outbreak in December 2016 up to 31 May 2017, there were 3,240 suspected cases of yellow fever reported (792 confirmed, 1,929 discarded, and 519 under investigation), including 435 deaths (274 confirmed, 124 discarded, and 37 under investigation). The case fatality rate (CFR) among confirmed cases is 35%. According to the probable site of infection,1 suspected cases correspond to 407 municipalities, while the confirmed cases were distributed among 130 municipalities in 8 states (Espírito Santo, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Minas Gerais, Pará, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Tocantins) and the Federal District. With regard to the confirmed fatal cases and their probable site of infection, one corresponds to the Federal District, 85 to Espírito Santo, one to Goiás, one to Matto Grosso, 165 to Minas Gerais, four to Pará, 7 to Rio de Janeiro, and 10 to São Paulo. In the states with more than 5 confirmed deaths, the CFR among confirmed cases is 50% in São Paulo, 41% in Rio de Janeiro, 34% in Minas Gerais, and 33% in Espírito Santo. No cases were confirmed in new municipalities in Espírito Santo (ES), Minas Gerais (MG), São Paulo (SP), and Rio de Janeiro (RJ) in the last month. -

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001†

Exploratory Temporal and Spatial Distribution Analysis of Dengue Notifications in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazilian Amazon, 1999-2001† by Maria Goreti Rosa-Freitas*, Pantelis Tsouris**#, Alexander Sibajev***, Ellem Tatiani de Souza Weimann**, Alexandre Ubirajara Marques**, Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira** and José Francisco Luitgards-Moura*** *Laboratório de Transmissores de Hematozoários, Departamento de Entomologia, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Av. Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil **Núcleo Avançado de Vetores – Convênio FIOCRUZ-UFRR BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil ***Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, UFRR, BR 174 S/N - Boa Vista, RR, Brasil Abstract In Brazil, as in the rest of the world, dengue has become the most important arthropod-borne viral disease of public health significance. Roraima state presented the highest dengue incidence coefficient in Brazil in the last few years (224.9 and 164.2 per 10,000 inhabitants in 2000 and 2001, respectively). The capital, Boa Vista, reports the highest number of dengue cases in Roraima. This study examined the temporal and spatial distribution of dengue in Boa Vista during the years 1999- 2001, based on daily notifications as recorded by local health authorities. Temporally, dengue notifications were analysed by weekly and monthly averages and age distribution and correlated to meteorological variables. Spatially, dengue coefficients, premises infestation indices, population density and income levels were allocated in a geographical information system using, Boa Vista 49 neighbourhoods as units. Dengue outbreaks displayed distinct year-to-year distribution patterns that were neither periodical nor significantly correlated to any meteorological variable. There were no preferences for age and sex. -

Um Estudo Sobre Amapá E Roraima

ISSN 1415-4765 TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO NO 683 Federalismo, Repasses Federais e Crescimento Econômico: um Estudo sobre Amapá e Roraima Bruno de Oliveira Cruz Carlos Wagner de Albuquerque Oliveira Brasília, novembro de 1999 ISSN 1415-4765 TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO NO 683 Federalismo, Repasses Federais e Crescimento Econômico: um Estudo sobre Amapá e Roraima* Bruno de Oliveira Cruz** Carlos Wagner de Albuquerque Oliveira** Brasília, novembro de 1999 * Os autores agradecem a Mônica Mora, Antônio Carlos Galvão, Herton Araújo, Nelson Zackseski, Maria Cris- tina Macdowell, Luciana Mendes, Salvador Viana e Humberto Watson pelos comentários, sugestões e auxílio para o término desta pesquisa. ** Pesquisadores da Diretoria de Políticas Regionais e Urbanas do IPEA. MINISTÉRIO DO PLANEJAMENTO, ORÇAMENTO E GESTÃO Martus Tavares – Ministro Guilherme Dias – Secretário Executivo Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada Presidente Roberto Borges Martins DIRETORIA Eustáquio J. Reis Gustavo Maia Gomes Hubimaier Cantuária Santiago Luís Fernando Tironi Murilo Lôbo Ricardo Paes de Barros Fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, o IPEA fornece suporte técnico e institucional às ações governamentais e torna disponíves, para a sociedade, elementos necessários ao conhecimento e à solução dos problemas econômicos e sociais do país. Inúmeras políticas públicas e programas de desenvolvimento brasileiro são formulados a partir dos estudos e pesquisas realizados pelas equipes de especialistas do IPEA. TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO tem o objetivo de divulgar resultados de estudos desenvolvidos direta ou indiretamente pelo IPEA, bem como trabalhos considerados de relevância para disseminação pelo Instituto, para informar profissionais especializados e colher sugestões. Tiragem: 115 exemplares COORDENAÇÃO DO EDITORIAL Brasília – DF: SBS Q. 1, Bl. -

Nova Califórnia MACHADINHO

MINISTÉRIO DE MINAS E ENERGIA MINISTÉRIO DA SAÚDE SECRETARIA DE MINAS E METALURGIA FUNDAÇÃO NACIONAL DE SAÚDE 67º 66º 65º 64º 63º 62º 61º 60º 8º 8º A EIR MAD PORTO VELHO AMAZONAS RIO AMAZONAS PORTO VELHO CANDEIAS DO JAMARI RIO DO A Distrito de MAC H 9º 9º JAMARI Nova Califórnia MACHADINHO BR-364 ABU RIO NÃ BURITIS ARIQUEMES MATO 10º ACRE GROSSO 10º NOVA 5 2 MAMORÉ -4 R CAMPO B R I NOVO O 80Km GOVERNADOR JORGE TEIXEIRA MIRANTE M DA SERRA 11º A 11º M O R É ALVORADA CACOAL ESPIGÃO GUAJARÁ-MIRIM D'OESTE D'OESTE B SÃO ROLIM DE SERINGUEIRAS MIGUEL B MOURA R -3 64 12º O 12º ALTA FLORESTA PARECIS COSTA MARQUES CHUPINGUAIA L SÃO FRANCISCO VILHENA D'OESTE Í RIO V G UA 13º POR CORUMBIARA 13º I É A MATO GROSSO 67º 66º 65º 64º 63º 62º 61º 60º NOVA CALIFÓRNIA Mapa político do Estado de Rondônia com a localização do distrito de Nova Califórnia. AVALIAÇÃO DO POTENCIAL HIDROGEOLÓGICO DA ÁREA URBANA DO DISTRITO DE NOVA CALIFÓRNIA MUNICÍPIO DE PORTO VELHO RO NACIO O NA ÇÃ L A D D E N S U A F Ú D CPRM FNS E E M D Ú I A NI S Serviço Geológico do Brasil STÉRIO DA RESIDÊNCIA DE PORTO VELHO COORDENAÇÃO REGIONAL DE RONDÔNIA JULHO 1999 MINISTÉRIO DE MINAS E ENERGIA SECRETARIA DE MINAS E METALURGIA Rodolfo Tourinho Neto Ministro de Estado José Luiz Péres Garrido Secretário Executivo Luciano de Freitas Borges Secretário de Minas e Metalurgia CPRM SERVIÇO GEOLÓGICO DO BRASIL Geraldo Gonçalves Soares Quintas Diretor Presidente Umberto Raimundo Costa Diretor de Geologia e Recursos Minerais Thales de Queiroz Sampaio Diretor de Hidrologia e Gestão Territorial Paulo Antônio Carneiro Dias Diretor de Relações Institucionais e Desenvolvimento José Sampaio Portela Nunes Diretor de Administração e Finanças Frederico Cláudio Peixinho Chefe do Departamento de Hidrologia Humberto J. -

Mapa Geológico Do Estado De Rondônia Geological

MINISTÉRIO DE MINAS E ENERGIA SECRETARIA DE MINAS E METALURGIA o CPRM - SERVIÇO GEOLÓGICO DO BRASIL 63 SUPERINTENDÊNCIA REGIONAL DE MANAUS 80 8o RESIDÊNCIA DE PORTO VELHO BR-319 RIO MADEIRA Preto RIO MAPA GEOLÓGICO DO ESTADO DE RONDÔNIA JI-PARAN Rio GEOLOGICAL MAP OF RONDÔNIA STATE LISTAGEM DOS RECURSOS MINERAIS / LISTING OF MINERAL RESOURSES Á o SUBSTÂNCIA LOCAL / MUNICÍPIO UNIDADE ESTRATIGRÁFICA N 6Au AMAZONAS COMMODITY PLACE / MUNICIPALITY STRATIGRAPHIC UNIT OU 640 01 Ouro / Belmont / Porto Velho QHa Gold Rio 02 Argila / Clay Belmont / Porto Velho QHa 4Au MACHADO 03 Ouro / Gold Quintelândia / Porto Velho QHa ari 3Au Verde 04 Ouro / Gold Cujubim / Porto Velho QHa Jam 05 Argila / Clay Portochuelo / Porto Velho QHa 2ag ESCALA /SCALE 1:1.000.000 1Au 5ag 06 Ouro / Gold Balsa / Porto Velho QHa 07 Argila / Clay Candeias / Porto Velho TQi Rio 20 km 0 20 40 60 80 100 km 08 Ouro / Gold Santo Antônio / Porto Velho Mst 09 Granito / Pedra Grande / Candeias do Jamari Mac 208ag 620 Granite UHE 10 Granito / Granite 5º BEC / Porto Velho Mst PORTO VELHO de Samuel 11 Estanho / Tin Maria Conga / Porto Velho Mst AMAZONAS 7ag Candeias Rio MINISTRO DE MINAS E ENERGIA / MINISTER OF MINES AND ENERGY 12 Estanho / Tin Furado do Couro / Costa Marques QHa do Jamari 13 Estanho / Tin Serra dos Reis / Costa Marques TQi 8Au 9gr São RODOLPHO TOURINHO NETO Rio 1999 14 Estanho / Tin Serra dos Reis / Costa Marques TQi 234gr á Curicaca á Jo ru ão 15 Estanho / Tin Limoeiro / São Francisco do Guaporé QHp 126gr Ig. Ig. SECRETÁRIO EXECUTIVO / EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Ju Sã 16 Estanho -

Convergent Agrarian Frontiers in the Settlement of Mato Grosso, Brazil

Convergent Agrarian Frontiers in the Settlement of Mato Grosso, Brazil Lisa Rausch University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies Abstract: The heterogeneity of development in the contemporary southern Amazon may be linked to different settlement experiences on the frontier. Three main types of productive settlement have been identified, including official colonization, private colonization, and spontaneous settlement, based on the differentiated motivations and resources of participants in these settlements. Not only did these different types of frontiers advance concurrently in the Amazon, but these frontiers sometimes converged in one location. The interaction of settlers from different groups sometimes created conflict, but also advanced the process of territorialization of the Amazon. This position is illustrated via a case study of one municipality at which three groups of settlers converged. Ultimately, though local popular history privileges the role of one of the three groups in bringing about the founding of the municipality and the development of a successful local economy, these achievements were only possible due to the different resources that each group brought to the settlement. Introduction he heterogeneity of the Brazilian Amazon frontier experience is just beginning to be understood. Early researchers set out structuralist expectations of accelerating resource Texploitation, capital accumulation by a relative few as land holdings were systematically consolidated, and the enlistment of the peasantry into wage labor as the agricultural frontier advanced into the Amazon.1 A linear progression toward the homogenization of Amazonian places has not occurred, however, even as highly capitalized industrial agriculture has continued to advance in the region.2 Today, the Amazon is a tapestry of highly globalized and globalizing cities, relic frontier towns, marginal extractive landscapes, and panoramas of modern, industrial- scale agricultural production with a range of landholding sizes. -

Chapter 3 the North- Lost in the Amazon

BRAZIL Chapter 3 The North- Lost in the Amazon Have you ever heard about Amazon rainforest? Let us learn together! The equatorial North, also known as the Amazon or Amazônia, is Brazil's largest region with total landmass of 3,869,638 square kilometers, covering 45.3 percent of the national territory. Way too big and enormous!! It is also the least inhabited part of the country. 31 BRAZIL The region has the largest rainforest of the world and is called Amazon. The word Amazon refers to the women warriors who once fought in inter-tribe in ancient times in this region of today's North Region of Brazil. It is also the name of one of the major river that passes through Brazil and flows eastward into South Atlantic. This river is also the largest of the world in terms of water carried in it. There are also numerous other rivers in the area. It is one fifth of all the earth's fresh water reserves. There are two main Amazonian cities: Manaus, capital of the State of Amazonas, and Belém, capital of the State of Pará. 32 BRAZIL Over half of the Amazon rainforest( more than 60 per cent) is located in Brazil but it is also located in other South American countries including Peru, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Guyana, Bolivia, Suriname and French Guiana. The Amazon is home to around two and a half million different insect species as well as over 40000 plant species. There are also a number of dangerous species living in the Amazon rainforest such as the “Onça Pintada” (Brazilian Puma) and anaconda.