Bellerophon Was Raised by His Mother, Which Was His First Downfall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Ancient Greece. ¡ the Basilisc Was an Extremely Deadly Serpent, Whose Touch Alone Could Wither Plants and Kill a Man

Ancient Greece. ¡ The Basilisc was an extremely deadly serpent, whose touch alone could wither plants and kill a man. ¡ The creature is later shown in the form of a serpent- tailed bird. ¡ Cerberus was the gigantic hound which guarded the gates of Haides. ¡ He was posted to prevent ghosts of the dead from leaving the underworld. ¡ Cerberus was described as a three- headed dog with a serpent's tail, a mane of snakes, and a lion's claws. The Chimera The Chimera was a monstrous beast with the body and maned head of a lion, a goat's head rising from its back, a set of goat-udders, and a serpents tail. It could also breath fire. The hero Bellerophon rode into battle to kill it on the back of the winged horse Pegasus. ¡ The Gryphon or Griffin was a beast with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion. ¡ A tribe of the beasts guarded rich gold deposits in certain mountains. HYDRA was a gigantic, nine-headed water-serpent. Hercules was sent to destroy her as one of his twelve labours, but for each of her heads that he decapitated, two more sprang forth. So he used burning brands to stop the heads regenerating. The Gorgons The Gorgons were three powerful, winged daemons named Medusa, Sthenno and Euryale. Of the three sisters only Medousa was mortal, and so it was her head which the King commanded the young hero Perseus to fetch. He accomplished this with the help of the gods who equipped him with a reflective shield, curved sword, winged boots and helm of invisibility. -

Pegasus Back from Kenya Sgt

Hawaii Marine CCE Graduates Bodybuilder A-5 Volume 29, Number 23 Serving Marine Corps Base Hawaii June 8, 2000 B-1 A1111111111111111W 1111111111- .111111111111164 Pegasus back from Kenya Sgt. Robert Carlson Natural Fire provided valuable training for "Communications with the JTF headquar- Press Chief the detachment, according to Capt. ters was difficult at times, as was getting Christopher T. Cable, detachment mainte- maintenance parts here all the way from The Marines of Marine Heavy Helicopter nance officer. They not only experienced Hawaii," Cable explained. "Everyone did a Squadron 463 returned to Hawaii Saturday breaking down and deploying their CH-53D great job though, and we were able to get our after their month-long deployment to Kenya "Sea Stallions," they gained the experience of job done without any problems." in support of Operation Natural Fire. overcoming challenges inherent while con- Cable said the Marines in the detachment Working side-by-side with the U.S. Army, ducting operations in a foreign country. are happy to be back in Hawaii. Navy, and Air Force, Pegasus provided airlift "We were located on an airfield in the city "There are a lot of experienced Marines support for medical assistance and humanitar- of Mombasa, Kenya, about 70 miles south of here, but there are also many who are new to ian operations during the joint-combined the Joint Task Force headquarters in Malindi," the squadron," he said. "This evolution operation. said Cable. "The crew had the chance to see allowed the newer members of the squadron a The detachment of Hawaii Marines assist- what it takes to have two helicopters on-call chance to experience everything involved in ed in training Kenyan, Ugandan and 24 hours a day." deploying to a foreign country. -

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/xs25j Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

Land of Myth Odyssey Players

2 3 ἄνδρα µοι ἔννεπε, µοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς µάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν· πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυµόν, ἀρνύµενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. Homer’s Odyssey, Book 1, Lines 1-5 (ΟΜΗΡΟΥ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, ΡΑΨΟΔΙΑ 1, ΣΤΙΧΟΙ 1-5) CREDITS INDEX Credits – The Land of Myth™ Team Written & Designed by: John R. Haygood Art Direction: George Skodras, Ali Dogramaci Who We Are .............................................................................................. 6 Cover Art: Ali Dogramaci What is this Product ................................................................................. 6 Proofreading & Editing: Vi Huntsman (MRC) This is a product created by Seven Thebes in collaboration with the Getty Museum Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 in Los Angeles, USA. Special thanks for the many hours of game testing and brainstorming: Safety and Consent .................................................................................. 10 Thanasis Giannopoulos, Alexandros Stivaktakis, Markos Spanoudakis The Land of Myth Mechanics: A Rules-Light Version ...................... 12 First Edition First Release: November 2020 Telemachos and His Quest ................................................................... 24 Character Sheets ...................................................................................... 26 Playtest Material V0.3 Please note that this game is still -

Greek Characters

Amphitrite - Wife to Poseidon and a water nymph. Poseidon - God of the sea and son to Cronos and Rhea. The Trident is his symbol. Arachne - Lost a weaving contest to Athene and was turned into a spider. Father was a dyer of wool. Athene - Goddess of wisdom. Daughter of Zeus who came out of Zeus’s head. Eros - Son of Aphrodite who’s Roman name is Cupid; Shoots arrows to make people fall in love. Demeter - Goddess of the harvest and fertility. Daughter of Cronos and Rhea. Hades - Ruler of the underworld, Tartaros. Son of Cronos and Rhea. Brother to Zeus and Poseidon. Hermes - God of commerce, patron of liars, thieves, gamblers, and travelers. The messenger god. Persephone - Daughter of Demeter. Painted the flowers of the field and was taken to the underworld by Hades. Daedalus - Greece’s greatest inventor and architect. Built the Labyrinth to house the Minotaur. Created wings to fly off the island of Crete. Icarus - Flew too high to the sun after being warned and died in the sea which was named after him. Son of Daedalus. Oranos - Titan of the Sky. Son of Gaia and father to Cronos. Aphrodite - Born from the foam of Oceanus and the blood of Oranos. She’s the goddess of Love and beauty. Prometheus - Known as mankind’s first friend. Was tied to a Mountain and liver eaten forever. Son of Oranos and Gaia. Gave fire and taught men how to hunt. Apollo - God of the sun and also medicine, gold, and music. Son of Zeus and Leto. Baucis - Old peasant woman entertained Zeus and Hermes. -

Chaining Bellerophon: on Ethics and Pride

Commentary MICHAEL CAVENDISH Chaining Bellerophon: On Ethics and Pride THE TALE FROM Greek mythology about able, intractable monsters of injustice. And, to retreat further into the figurative, we have lawyers in gener- Bellerophon proceeds like this. Bellerophon al, who, finding themselves in what is often the zero- was the greatest warrior of his age. He rode Pe- sum universe of the criminal and the civil law—one side does usually fare better than the other—feel the gasus, the winged flying horse. Bellerophon flush of success and the subsequent Bellerophonic wielded a great spear and slayed an unbeat- impulse to move on to some feat that is even larger than the one that came before. Lawyers need able, intractable monster: the Chimera. Return- Bellerophon, because the lesson to be learned from ing home, the warrior quickly became bored, Bellerophon’s story is the imperiling nature of hubris (a billowing pride) specifically and pride more gen- then—much to his regret—decided to ride Pe- erally. Pride and lessons following even mild humiliation gasus up to the peak of Mount Olympus to rub or embarrassment catalyzed by pride-based vignettes elbows with his equals—the gods. But the peak are an inescapable part of the human experience. The last such incident for me occurred when I trav- was too far for him, and his successes came to eled to a mixed meeting of potentates and peons (I an end: Bellerophon died. was the peon) who were presiding over an audit of a large and rich state government agency during my home state’s gubernatorial transition. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

Press Release

Press Release German Workmanship for the USA Pegasus & Dragon at Gulfstream Park, Miami, USA: Strassacker art foundry creates largest bronze horse sculpture in the world The Strassacker art foundry has implemented the vision of numerous architects, town plan- ners and artists. The list of national and international references is just as long. After all, the complete processing of small-scale and complex art projects from conceptualisation through coordination of the artists, architects, authorities and companies involved, right through to the final assembly stage is among the core competencies of the company from Süßen. "But when the first sketches of Pegasus & Dragon arrived in Süßen for review around three years ago, even the most experienced members of staff initially looked at it in disbelief", recollect Edith Strassacker and Günter Czasny. "The bronze statue Pegasus & Dragon was already one of the greatest challenges in our company's history, which spans close to a century", report the presiding managing director and the deputy managing direc- tor of the family-owned company that employs 500 members of staff. Even motorists travelling along the busy U.S. Highway 1 in Miami, Florida, over the past few months have wondered, in astonishment, what was being constructed close to Hallandale Beach in Gulfstream Park. The 33-metre-high metal structure that gleams in the sun and that took up to 100 workers to create, all of them working in tandem, was the talk of the town on the legendary federal highway that runs the length of the East Coast of the USA. The result that emerged upon conclusion of construction in November 2014 is no less spec- tacular. -

Blizzard Bag 1: Bellerophon and Atlanta

THE MYTH OF BELLEROPHON Bellerophon was a good looking young man, and the master of the winged horse, Pegasus. He was so handsome that a queen fell in love with him, but Bellerophon did not feel the same way about her. The queen was broken hearted, and asked the king to kill Bellerophon. Unable to kill him himself, the king sent Bellerophon to see King Lycia, who he has asked to kill Bellerophon for him. The king of Lycia was unable to kill Bellerophon as well. Instead, he came up with a plan – he decided to send Bellerophon on a very difficult quest, THE MYTH OF BELLEROPHON with the hope of him dying in the process. He asked Bellerophon to kill the Chimera, a ferocious creature with the head of a lion and the body of a goat. Bellerophon accepted the challenge. Because he was master of the mighty Pegasus, he was able to fly high above the Chimera. Because the Chimera was unable to get close to him, Bellerophon was able to kill it with his bow and arrow. After this heroic deed, Bellerophon became quite arrogant. He thought his actions should allow him to sit among the gods at Mount Olympus. Pegasus had no time for his arrogance, and promptly threw him off. As a punishment for his arrogance, Bellerophon was left on Earth alone, and the mighty Pegasus was brought to Mount Olympus to live among the gods. THE MYTH OF BELLEROPHON MYTH SUMMARY WHO WERE THE MAIN CHARACTERS? WHERE DID IT TAKE PLACE? WHAT WERE THE MAIN EVENTS? USE THE INFORMATION YOU GATHERED TO SUMMARIZE THE STORY HERE. -

Summary of a Game Cycle

SUMMARY OF A GAME CYCLE 1 - UPDATE THE MYTHOLOGICAL CREATURES TRACK 2 - UPDATE THE GODS TRACK 3 - REVENUE Each player gets 1 GP for each prosperity marker controlled 4 - OFFERINGS In the order indicated by the offering markers on the turn track: s"IDONTHEVARIOUS'ODS s/NCEEVERYPLAYERHASSUCCESSFULLYBID PAYYOUROFFERING 5 - ACTIONS 0ERFORM INTHEORDEROFYOURCHOICEBYPAYINGTHEINDICATEDCOST s4HEACTIONSSPECIlCTOYOUR'OD s!CTIONSTIEDTOANY-YTHOLOGICAL#REATURERECRUITEDTHISTURN 4HENMOVEYOUROFFERINGMARKERTOTHETURNTRACK 4HIS MARKER MUST BE PLACED ON THE SPACE WITH THE HIGHEST NUMBERSTILLFREE )F ATTHEENDOFACYCLE ASINGLEPLAYEROWNSTWO-ETROPOLISES HE ISTHEWINNER)FMORETHANONEPLAYEROWNSTWO-ETROPOLISES THE TIE BREAKERISTHEAMOUNTOF'0EACHHAS MYTHOLOGICAL CREATURES THE FATES SATYR DRYAD Recieve your revenue again, just like Steal a Philosopher from the player Steal a Priest from the player of SIREN PEGASUS GIANT at the beginning of the Cycle. of your choice. your choice. Remove an opponent’s fleet from Designate one of your isles and Destroy a building. This action can the board and replace it with one move some or all of the troops on be used to slow down an opponent of yours. If you no longer have any it to another isle without having to or remove a troublesome Fortress. The Kraken, the Minotaur, Chiron, The following 4 creatures work the same way: place the figurine on the isle of fleets in reserve, you can take one have a chain of fleets. This creature The Giant cannot destroy a Metro- Medusa and Polyphemus have a your choice. The power of the creature is applied to the isle where it is until from somewhere else on the board. is the only way to invade an oppo- polis. figurine representing them as they the beginning of your next turn. -

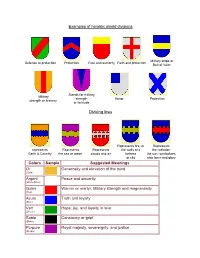

Examples of Heraldic Shield Divisions Dividing Lines Colors Sample

Examples of heraldic shield divisions Military strips or Defense or protection Protection Rule and authority Faith and protection Belt of Valor Stands for military Military strength Honor Protection strength or bravery. or fortitude. Dividing lines Represents fire, or Represents represents Represents Represents the walls of a the radiation Earth & Country the sea or water clouds and air fortress the sun. symbolizes or city also fame and glory Colors Sample Suggested Meanings Or Generosity and elevation of the mind (Gold) Argent Peace and sincerity (White/Silver) Gules Warrior or martyr; Military strength and magnanimity (Red) Azure Truth and loyalty (Blue) Vert Hope, joy, and loyalty in love (Green) Sable Constancy or grief (Black) Purpure Royal majesty, sovereignty, and justice (Purple) Tenne Worthy ambition (Orange) Sanguine Patient in battle, and yet victorious (Maroon) v Charges: Suggested Meanings: Acacia Branch Eternal and affectionate remembrance both for the living and the dead. Acorn Life, immortality and perseverence Anchor Christian emblem of hope and refuge; awarded to sea warriors for special feats performed Also signifies steadfastness and stability. In seafaring nations, the anchor is a symbol of good luck, of safety, and of security Annulet Emblem of fidelity; Also a mark of Cadency of the fifth son Antelope Represents action, agility and sacrifice and a very worthy guardian that is not easily provoked, but can be fierce when challenged Antlers Strength and fortitude Anvil Honour and strength; chief emblem of the smith's trade Arrow Readiness; if with a cross it denotes affliction; a bow and arrow signifies a man resolved to abide the uttermost hazard of battle.