1 Contact Info Peter Galison & Robb Moss Directors/Producers Info

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

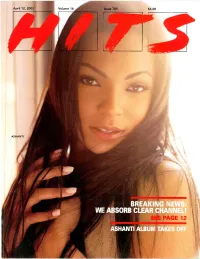

April 12, 2002 Issue

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

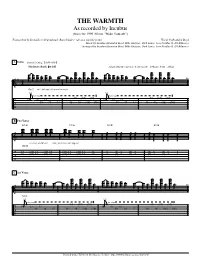

The Warmth Guitar Tab

THE WARMTH As recorded by Incubus (from the 1999 Album "Make Yourself") Transcribed by Donald (w/ Grungehead "Razorblade's" tab as a starting point) Words by Brandon Boyd Music by Incubus (Brandon Boyd, Mike Einziger, Dirk Lance, Jose Pasillas II, DJ Kilmore) Arranged by Incubus (Brandon Boyd, Mike Einziger, Dirk Lance, Jose Pasillas II, DJ Kilmore) A Intro Standard tuning : E-A-D-G-B-E Moderate Rock P = 145 All parenthesized notes are delay repeats 1/8th note delay = 206ms V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V 6x 1 g 4 u u I 4 u u Gtr I w/ 1/8th note delay and tremolo 1/2 1/2 M let ring M let ring 19 (19) (19) 19 (19) (19) T 19 19O 17 17 19 19O 17 17 A 19 19 17 17 16 16 (16) (16) 19 19 17 17 16 16 (16) (16) B B Pre-Verse E5/B C5/G G5/D E5/B V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V 5 u u u V V V V V V V V V V I u u u u w/ delay and phaser (play with pick and fingers) u Gtr II T 17 (17) 17 (17) 17 (17) 13 (13) 13 13 8 (8) 8 (8) 8 (8) 5 (5) 5 5 A 16 (16) 16 (16) 16 (16) 12 (12) 12 12 7 (7) 7 (7) 7 (7) 4 (4) 4 4 B C 1st Verse V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V 4x 9 u u I w/ 1/8th note delay andu tremolo u Gtr I 1/2 1/2 M let ring M let ring 19 (19) (19) 19 (19) (19) T 19 19O 17 17 19 19O 17 17 A 19 19 17 17 16 16 (16) (16) 19 19 17 17 16 16 (16) (16) B Printed using TabView by Simone Tellini - http://www.tellini.org/mac/tabview/ THE WARMTH - Incubus Page 2 of 4 D 1st Chorus E5/B C5/G G5/D E5/B V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V 4x 13 V V V V V V V V V V I u w/ delay andu phaser (play -

NIGHT out Incubus Offers

25 NIGHT OUT SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2011 MUSIC Eleanor Ellis sings the blues at Kennedy’s Millennium Stage By Marie Gullard Special to The Washington Examiner ONSTAGE Whether she sings or speaks, no Eleanor Ellis one listening to blues artist Elea- » Where: Millennium Stage, nor Ellis mistakes if for anything Kennedy Center, 2700 F St. other than pure New Orleans. Her NW ● music, performed Sunday at Ken- » When: 6 p.m. Sunday nedy Center’s Millennium Stage, » Info: Free; 800-444-1324 or is an delightful of her Louisiana 202-467-4600; kennedy- upbringing. center.org “I think you absorb the culture CORY SCHWARTZ/GETTY IMAGES FILE that you grew up in,” she said. “A Incubus is touring behind its first album in five years, “If Not Now, When?,” including a stop at Merriweather Post Pavilion. lot of the music I grew up with, I couplel of f good d ffriends i d at t theth Millen-Mill found out later was indigenous to nium show. She will be using locals Louisiana. I didn’t know that back Jay Summerour on harmonica and Incubus offers ‘If Not Now, When’ then; I thought everyone listened to percussionist Eric Selby on the this music.” snare drums. As a product of her blues envi- The trio will play a one-hour set By Nancy Dunham glimmer of hope, that is what kept ronment, Ellis was able to transition list. Ellis expects to do two songs by Special to The Washington Examiner us going.” ONSTAGE smoothly to the D.C. scene with a gig an early artist that influenced her, That type of musical passion still ● back in the early 1980s. -

Calabasas City Los Angeles County California, U

CALABASAS CITY LOS ANGELES COUNTY CALIFORNIA, U. S. A. Calabasas, California Calabasas, California Calabasas is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, Calabasas es una ciudad en el condado de Los Ángeles, California, Estados located in the hills west of the San Fernando Valley and in the northwest Santa Unidos, ubicada en las colinas al oeste del valle de San Fernando y en el noroeste Monica Mountains between Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hidden de las montañas de Santa Mónica, entre Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hills, and Malibu, California. The Leonis Adobe, an adobe structure in Old Hidden Hills y Malibu, California. El Adobe Leonis, una estructura de adobe en Town Calabasas, dates from 1844 and is one of the oldest surviving buildings Old Town Calabasas, data de 1844 y es uno de los edificios más antiguos que in greater Los Angeles. The city was formally incorporated in 1991. As of the quedan en el Gran Los Ángeles. La ciudad se incorporó formalmente en 1991. A 2010 census, the city's population was 23,058, up from 20,033 at the 2000 partir del censo de 2010, la población de la ciudad era de 23.058, en census. comparación con 20.033 en el censo de 2000. Contents Contenido 1. History 1. Historia 2. Geography 2. Geografía 2.1 Communities 2.1 Comunidades 3. Demographics 3. Demografía 3.1 2010 3.1 2010 3.2 2005 3.2 2005 4. Economy 4. economía 4.1. Top employers 4.1. Mejores empleadores 4.2. Technology center 4.2. -

A Hard Days Night Angie About a Girl Acky Breaky Heart All Along the Watchtowers Angels All the Small Things Ain`T No Sunshine A

A hard days night Angie About a girl Acky breaky heart All along the watchtowers Angels All the small things Ain`t no sunshine All shook up Alberta Alive And I love her Anna (go to him) 500 miles 7 nation army Back to you Bad moon rising Be bop a lula Beds are burnng Big monkey man Bitter sweet symphony Big yellow taxi Blue suede shoes Born to be wild Breakfast at Tiffany`s Bonasera Brown eyed girl Can`t take my eyes off of you Californication Change the world Cigarettes and alcohol Cocain blues Baby,Come back Chasing cars Come together Creep Come as you are Cocain Cotton fields Crazy Country roads Crazy little thing called love Dont look back in anger Don't worry be happy Dancing in the moonlight Don`t stop belivin` Dance the night away Dead or alive Englishman in NY Every breath you take Easy Faith Feel like making love Fortunate son Fields of gold Further on up the road Free falling Gimme all your lovin' Gimme love Gimme all your love Great balls of fire Green grass of home Happy Hello Heart-shaped box Have you ever seen the rain Hello Mary Lou Highway to hell High and dry Hey jude Hotel california Human touch Hurt Hound dog (ISun Can't is shining Get No) Satisfaction I'm yours I don't wanna miss a thing I saw her staning there I got stripes I walk the line Imagine I`m a believer It`s my life (D) Impossible Jamming Johny be goode Keep on rockin` in a free world Knockin` on the heavens door Kingston town La bamba (E) Lay down Sally Learn to fly Light my fire Let her go Let it be Love is all around Layla Learning to fly Living next door -

WPU Remembers 9/11

* WEEKLY MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2002 William Paterson University • Volume 69 No. 2 FREE Plans for Student Center expansion underway ByjimSchofield the problems. Finally, some News Editor aspects of the plan may change due to building codes. ""This is another step along Urinyi said that distribu- the planned and timely growth, tion of offices in the renovat- [of the University]" said ed Student Center is not com- President Speert at the opening plete. This will likely be a of the new Valley Road matter among the various Building, and he meant-it. Plans departments that will be for a $40 million expansion of using the space, including the Student Center are well Hospitality Services, the underway with the intention of Office of Campus Activities breaking ground next summer and Student Leadership, the . according to John Urinyi, Women's Center, the Student Director of Capital- Planning, Government Association and 9/11 memorial outside Student Center photo by Elizabeth Fowler Design and Construction. all affiliated Student According to Urinyi, the Organization and, possibly, expansion will include a'near the office of the Dean of complete renovation of the Student Development Dr. WPU remembers 9/11 existing Student Center facili- John Mar tone- - ties; an addition to the Zanfino The existing Machuga Plaza side of the Student Center Student Center is over 30 By Lori Michael an original poem called September 11 affected their and a new building containing years old. Urinyi, along with The Beacon "Prayer." Miryam Wahrman, lives. The WPU Gospel Choir rooms, and will offer 60,000 'Afimihistration aha stnance • square feet of new space for Steve Bolyai and Tim montage of pictures greeted son, Jeremy, was one of the that was both somber and student organization offices, the Fanning, visited many other students, staff and faculty as passengers who tried to take uplifting. -

Stärkste Momente Facts Cover Und Titel

JAN 1997 FEB MÄR APR MAI JUN JUL Facts Cover und Titel Incubus S.C.I.E.N.C.E. Das von den Bandfreunden Chris McCann (Foto) und Frank Harkins (Design) gestal- tete Cover zeigt laut Brandon Boyd „einfach irgendein abstraktes Bild, das für uns Veröffentlicht am 9. September 1997 auf Epic/Immortal in dem Moment mit dem Thema Wissenschaft zusammenhing.“ Interessanter ist Aufgenommen zwischen Mai und Juni 1997 bei 4th Street der abgebildete Typ darauf, in der Band-Legende einfach „Chuck“ genannt. Fotos Recording, Santa Monica, produziert von Jim Wirt von ihm tauchen auf zahllosen frühen Flyern der Band auf, wie auch auf dem Laufzeit: 55:52 Cover der EP Enjoy Incubus. Um wen es sich dabei handelt, hielt die Band stets mysteriös, indem sie ständig andere Antworten darauf gab: Mal war es ein Porno- Incubus: Cornelius (aka Brandon Boyd, Gesang), Jawa Darsteller der 70er, mal ein Testimonial für Zigarettenwerbung aus den 60ern, (aka Mike Einziger, Gitarre), Dirk Lance (aka Alex Katunich, Bass), dann wieder ein Mitglied des UFO-Kults. Tatsächlich heißt der Kerl wohl Charles DJ Lyfe (aka Gavin Koppell, Turntables), Badmammajamma Mulholland, was genau er gemacht hat, weiß die Band selber nicht. Ähnlich myste- (aka Jose Pasillas, Drums) riös verhält es sich mit dem Titel, der eine Abkürzung für irgendetwas Schräges ist. VISIONS erzählte die Band damals, es heiße Southern California’s Incubus Enters Nirvana’s Can Equipment, gängiger ist allerdings die Deutung Sailing Catamarans Is Every Nautical Captain’s Ecstasy. Was auch immer es bedeutet, es macht eines klar: Damals ging es Incubus nicht um Botschaften oder Metaebenen, sondern nur um die gute Musik. -

Backyard of Party Booze, Grilling Ryan and Other Things You'll Enjoy Reynolds

LEBRON JAMES: THE STYLISH BALLER OLIVIA WILDE DOES GYMNASTICS FOR US! WIN AN iPAD2 P.113 SHARPLOOK BETTER · FEEL BETTER · KNOW MORE EVERYONE HOW TO THROW WANTS A THE ULTIMATE PIECE BACKYARD OF PARTY BOOZE, GRILLING RYAN AND OTHER THINGS YOU'LL ENJOY REYNOLDS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SURFING IN THE LAND THE UFC’S CAR EVER MADE OF BLOOD DIAMONDS IMAGE PROBLEM YOUR NEW SUMMER WARDROBE HAS ARRIVED JUNE- JU LY 2011 ONLINE SHARPFORMEN.COM Display until July 31ST, 2011 $4.95 LEBRON JAMES: THE STYLISH BALLER OLIVIA WILDE DOES GYMNASTICS FOR US! WIN AN iPAD2 P.113 SHARPLOOK BETTER · FEEL BETTER · KNOW MORE EVERYONE WANTS A FATHER'S PIECE DAY GUIDE OF GIFTS FOR RYAN 25DADS REYNOLDS YOUR NEW SUMMER SURFING IN THE LAND THE UFC’S WARDROBE HAS ARRIVED OF BLOOD DIAMONDS IMAGE PROBLEM HOW TO THROW THE ULTIMATE BACKYARD PARTY ONLINE SHARPFORMEN.COM 2011 JUNE-JULY B:16.25 in T:16 in S:15 in Converts gasoline to adrenaline. With its bold, dynamic AMG styling, the all-new 2012 SLK 350 instantly attracts attention. And with our dynamic handling package and 302 horsepower at your disposal, the ride is as exhilarating as its look. For ultimate closed-top cruising, raise the power retractable vario-roof and witness MAGIC SKY CONTROL – our innovative panoramic sunroof that adjusts from tinted to clear at the touch of a button. Visit mercedes-benz.ca/slk T:10.75 in S:9.75 in B:11 in © 2011 Mercedes-Benz Canada Inc. F:8 in F:8 in Ad Number: MBZ_CRC_P05938SH4 Publication(s): Sharp This proof was produced This ad prepared by: SGL Communications • 2 Bloor St. -

Your Donation Has Twice the Impact! See See P

Your Donation Has Twice the Impact! See See p. 23 and back cover for details JULY 2019 AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Chasing the Moon Part 1 8pm Monday, July 8 and 7pm Tuesday, July 16 Part 2 8pm Tuesday, July 9 and 7pm Tuesday, July 23 Part 3 8pm Wednesday, July 10 and 7pm Tuesday, July 30 Experience the thrilling era of the space race, from its earliest days to the 1969 moon landing. See story, p. 2 MONTANAPBS PROGRAM GUIDE MontanaPBS Guide On the Cover JULY 2019 · VOL. 33 · NO. 1 COPYRIGHT © 2019 MONTANAPBS, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MEMBERSHIP 1-866-832-0829 SHOP 1-800-406-6383 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.montanapbs.org ONLINE VIDEO PLAYER watch.montanapbs.org The Guide to MontanaPBS is printed monthly by the Bozeman Daily Chronicle for MontanaPBS and the Friends of MontanaPBS, Inc., a nonprofit corporation (501(c)3) PO Box 173340, Bozeman, MT 59717-3340. The publication is sent to contributors to MontanaPBS. Basic annual membership is $35. Nonprofit periodical postage paid at Bozeman, MT. PLEASE SEND CHANGE OF ADDRESS INFORMATION TO: MontanaPBS Membership, PO Box 173340, Bozeman, MT 59717-3340 COURTESY OF NASA, 1969 16, JULY KUSM-TV Channel Guide P.O. Box 173340 · Montana State University MPAN (Mont Public Affairs Network) Bozeman, MT 59717–3340 MontanaPBS World OFFICE (406) 994-3437 FAX (406) 994-6545 MontanaPBS Create Former President Lyndon B. Johnson (left E-MAIL [email protected] MontanaPBS Kids center) and Vice President Spiro Agnew (right BOZEMAN STAFF MontanaPBS HD center) view the liftoff of Apollo 11. GENERAL MANAGER Aaron Pruitt INTERIM DIRECTOR OF CONTENT/ Billings 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 CHIEF OPERATOR Paul Heitt-Rennie Butte/Bozeman 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Kristina Martin AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Great Falls 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 MEMBERSHIP/EVENTS MANAGER Erika Matsuda Helena 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 DEVELOPMENT ASST. -

As Recorded by Incubus (From the 2001 Album "Morning View")

ECHO As recorded by Incubus (from the 2001 Album "Morning View") Transcribed by Donald Words by Brandon Boyd Music by Incubus (Brandon Boyd, Mike Einziger, Dirk Lance, Jose Pasillas II, DJ Kilmore) Arranged by Incubus (Brandon Boyd, Mike Einziger, Dirk Lance, Jose Pasillas II, DJ Kilmore) A Intro P = 140 c c c 4x 1 4 V V k V V k V V V V V V V V V V k V V V V V V V V I 4 V gV V V V V V gV V V V gV V V V V V V V V V V V V Gtr I 1/2 1/2 let ring M let ring M let ring 0 (0) T 0 (0) 2 4 4 7 7 9 9 9 O9 7 7 4 4 7 7 4 (4) 4 4 4 O4 2 2 2 A 2 4 4 7 7 9 9 9 O9 7 7 4 4 7 7 4 (4) 4 4 4 O4 2 2 2 B 0 0 2 0 sl. sl. sl. sl. H sl. sl. sl. B Verse Dmaj6sus2 Bm c 5 W V V c W V V I W V V V V V gV V V V gW V V c gV W V V W W V let ring let ring let ring K 0 0 0 0 T K 0 0 0 0 G 3 3 K 2 2 (2) 2 K 4 4 (2) A K 0 0 4 4 4 4 K 4 4 (4) B K 0 0 K 2 2 K 0 0 L sl. -

Free Food Draws Crowd to Food Festival

WEDNESDAY, MAR. 5, 2008 VOL. 107 NO. 6 {http://mcluhan.unk.edu/antelope/www.unk.edu/theantelope/ { University of Nebraska at Kearney Run With It BY DANIEL APOLIUS characters and names on sheets of wore brightly colored garments in their traditional clothing. It’s from McCook said, “The African people that attend learn about each Free foodpaper for others in theirdraws traditional of blue, purple, yellow, crowd lavender such a difference fromto wearing dancersfood were by far my favorite, festival others’ cultures, and each year is Antelope Staff language. and red, creating a lively color shirts and jeans.” I just love their brightly colored an improvement from the last.” The International Food and Jordan VanWinkle, a junior contrast to the steel gray skies of Entertainment including pia- costumes.” Each delegate from the In- Cultural Festival has been en- from Chappell said, “This is a Nebraska. no solos, choreographed dances, Brenda Tichner a UNK ad- ternational Student Association tertaining and feeding UNK stu- great event for Kearney residents Kelsey Koch from Omaha fashion shows and karate demon- junct faculty member said, “This invested time and effort to ensure dents and Kearney residents since to experience the many cultures said, “I love that our international strations entertained the crowds is great. The diverse cultures in- this event was successful. 1976. that come to UNK.” students can share their culture while they ate ethnic dishes. volved interacting with one an- Rahima Ramanova a junior The festival drew crowds The delegate women involved with us, I really love to see them Jessica Fritsch a sophomore other mean that the students and from Uzbekistan said “It takes a young and old to watch the many lot of work to put on this festi- events and to enjoy the different val but it’s nice to see the smile dishes from around the world. -

Grammy-Nominated, Multi-Platinum Selling Band Incubus Announce 20Th Anniversary Tour for Acclaimed Make Yourself Album

May 6, 2019 Grammy-Nominated, Multi-Platinum Selling Band Incubus Announce 20th Anniversary Tour For Acclaimed Make Yourself Album Tickets On Sale To General Public Starting Friday, May 10 at 10am Local Time LOS ANGELES, May 6, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- Having sold more than 23 million albums to date, award winning band INCUBUS has announced today they will be hitting the road to celebrate the 20th anniversary of their platinum selling album Make Yourself. The Grammy- nominated band will take the 20 Years of Make Yourself & Beyond tour to 39 cities across the country, playing songs from that era as well as other songs spanning their career. Special guests Dub Trio, Wild Belle and Le Butcherettes will join on select dates. Produced by Live Nation, the tour will begin on Friday, September 13 at the Fillmore Auditorium in Denver, CO and will travel across cities such as Los Angeles, New York, Nashville and others before concluding Saturday, December 7 at the House of Blues Myrtle Beach. Please see below for full tour itinerary. Tickets for the tour will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, May 10 at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Incubus fan presales will begin tomorrow, May 7 at 10am local time. Incubus will also offer VIP upgrade packages for each show with options that include a backstage tour, on stage photo opportunity, invitation to the Incubus pre-show jam session, and access to watch the entire show from the side of the stage. For the first time, top tier VIP tickets will include access to MIXhalo www.mixhalo.com, a breakthrough audio enhancement that enables fans to hear what the band hears onstage.