Stories of Indigo Sarah Sutro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian History

Indian History Ancient History 1.Which of the following ancient Indian Kings had appointed Dhamma Mahamattas? [A] Asoka [B] Chandragupta Maurya [C] Kanishka [D] Chandragupta-II Correct Answer: A [Asoka] Notes: Dhamma Mahamattas were special officers appointed by Ashoka to spread the message of Dhamma or his Dharma. The Dhamma Mahamattas were required to look after the welfare of the people of different religions and to enforce the rules regarding the sanctity of animal life. 2.Who was the first Saka king in India? [A] Moga [B] Rudradaman [C] Azes [D] Ghatotkacha Correct Answer: A [ Moga ] Notes: An Indo-Scythian king, Moga (or Maues) was the first Saka king in India who established Saka power in Gandhara and extended supremacy over north-western India. 3.Who was ‘Kanthaka’ in the context of Gautam Buddha? [A] Charioteer [B] Body-guard [C] Cousin [D] Horse Correct Answer: D [ Horse ] Notes: Kanthaka was the royal horse of Gautama Buddha. 4.What symbol represents birth of Gautama Buddha? [A] Bodh tree [B] Lotus [C] Horse [D] Wheel Correct Answer: B [ Lotus ] Notes: Lotus and bull resembles the symbol of birth of Gautama Buddha. 5.What symbol represents nirvana of Gautama Buddha? [A] Lotus [B] Wheel [C] Horse [D] Bodhi Tree Correct Answer: D [ Bodhi Tree ] Notes: Bodhi Tree is the symbol of nirvana of Gautama Buddha. On the other hand, Stupa represents the symbol of death of Gautama Buddha. Further, The symbol ‘Horse’ signifies the renunciation of Buddha’s life. 6.During whose reign was the Fourth Buddhist Council held? [A] Ashoka [B] Kalasoka [C] Ajatsatru [D] Kanishka Correct Answer: D [ Kanishka ] Notes: The Fourth Buddhist Council was held at Kundalvana, Kashmir in 72 AD during the reign of Kushan king Kanishka. -

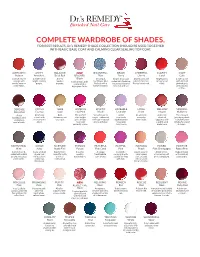

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Modern Indian Political Thought Ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context

Modern Indian Political Thought ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context Bidyut Chakrabarty Rajendra Kumar Pandey Copyright © Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajendra Kumar Pandey, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2009 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India www.sagepub.in SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Palatino by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chakrabarty, Bidyut, 1958– Modern Indian political thought: text and context/Bidyut Chakrabarty, Rajendra Kumar Pandey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Political science—India—Philosophy. 2. Nationalism—India. 3. Self- determination, National—India. 4. Great Britain—Colonies—India. 5. India— Colonisation. 6. India—Politics and government—1919–1947. 7. India— Politics and government—1947– 8. India—Politics and government— 21st century. I. Pandey, Rajendra Kumar. II. Title. JA84.I4C47 320.0954—dc22 2009 2009025084 ISBN: 978-81-321-0225-0 (PB) The SAGE Team: Reema Singhal, Vikas Jain, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma and Trinankur Banerjee To our parents who introduced us to the world of learning vi Modern Indian Political Thought Contents Preface xiii Introduction xv PART I: REVISITING THE TEXTS 1. -

Slow-Growing Microgreen Vegetables, Herbs & Flowers Comparison Charts

955 Benton Ave., Winslow, ME 04901 U.S.A. • Phone: Toll-Free 1-877-564-6697 • Fax: 1-800-738-6314 • Web: Johnnyseeds.com • Email: [email protected] SLOW-GROWING MICROGREEN VEGETABLES, HERBS & FLOWERS COMPARISON CHARTS Alfalfa Amaranth, Garnet Beet, Bull's Blood Beet, Early Wonder Tall Top Beet, Yellow Carrot Chard, Pink Stem Red & Red Beet Chicory, Bianca Dandelion, Red Magenta Spreen Orach, Ruby Red Purslane, Red Scallion & Shungiku Riccia Gruner Evergreen Hardy White Vegetables — Slow-Growing Microgreen Varieties (16–25 days) 5 Lbs. 25 Lbs. Part # Variety Description Flavor 1 Oz. 1/4 Lb. 1 Lb. @/Lb. @/Lb. 2150MG J Alfalfa Delicate appearance. Nutty, pea-like $3.75 $6.20 $10.80 $10.00 $9.50 2247MG J Amaranth, Garnet Red Fuchsia-colored leaves and stems. Mild, earthy $7.50 $15.05 $43.10 $38.40 $35.30 2912MG J $7.80 $16.60 $54.00 $47.70 $44.20 Beet, Bull's Blood Lofty. Red leaves, red stems. Earthy 2912M $6.75 $9.10 $25.50 $22.40 $21.00 123M Beet, Early Wonder Tall Top Lofty. Bright green leaves, red stems. Earthy $5.15 $6.75 $14.50 $11.30 $10.40 4544MG J NEW Beet, Red Beet Lofty. Bright green leaves, red stems. Earthy $6.25 $8.25 $18.70 $16.80 $14.50 2965MG J NEW Beet, Yellow $6.50 $8.75 $25.00 $22.50 $20.20 Lofty. Bright green leaves, yellow stems. Earthy 2965M Beet, Yellow $6.35 $8.45 $22.80 $19.60 $17.20 2468MG J $7.80 $16.10 $46.70 $43.60 $38.60 Carrot Feathery leaves. -

![Topic: Peasant Movements in the 19Th Century - Indigo Rebellion [NCERT Notes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0664/topic-peasant-movements-in-the-19th-century-indigo-rebellion-ncert-notes-490664.webp)

Topic: Peasant Movements in the 19Th Century - Indigo Rebellion [NCERT Notes]

UPSC Civil Services Examination UPSC Notes [GS-I] Topic: Peasant Movements in the 19th Century - Indigo Rebellion [NCERT Notes] The Indigo Rebellion (Neel Bidroho) took place in Bengal in 1859-60 and was a revolt by the farmers against British planters who had forced them to grow indigo under terms that were greatly unfavourable to the farmers. Causes of the Indigo Rebellion/Revolt Indigo cultivation started in Bengal in 1777. Indigo was in high demand worldwide. Trade in indigo was lucrative due to the demand for blue dye in Europe. European planters enjoyed a monopoly over indigo and they forced Indian farmers to grow indigo by signing fraudulent deals with them. The cultivators were forced to grow indigo in place of food crops. They were advanced loans for this purpose. Once the farmers took loans, they could never repay it due to the high rates of interest. The tax rates were also exorbitant. The farmers were brutally oppressed if they could not pay the rent or refused to do as asked by the planters. They were forced to sell indigo at non-profitable rates so as to maximize the European planters’ profits. If a farmer refused to grow indigo and planted paddy instead, the planters resorted to illegal means to get the farmer to grow indigo such as looting and burning crops, kidnapping the farmer’s family members, etc. The government always supported the planters who enjoyed many privileges and judicial immunities. Indigo Rebellion The indigo farmers revolted in the Nadia district of Bengal by refusing to grow indigo. They attacked the policemen who intervened. -

Roe-Guide.Pdf

WILD | NATURA L | SUSTAINABLE SUJIKO The cold, clean waters of Alaska provide a healthy, natural habitat for the five species of wild Alaska salmon. Each year, this e e raditional Japanese sujiko features salted and cured Alaska salmon roe within L e v e T the natural membrane or film (in-sac). Sujiko is a Japanese word composed t rich environment yields millions of high quality fish, famous S of “suji,” which means “line,” and “ko,” which means “child.” The name refers to the way in which the eggs are lined up in the ovary. The raw egg sacs are washed for their delicious flavor and superior texture. These same wild in a saturated brine solution, drained, packed with salt and then allowed to cure. All Alaska seafood is wild and sustainable and is managed Grading Information salmon produce some of the world’s finest roe, bursting with all Typically, there are three standard grades of sujiko: No.1, No.2 and No.3, plus for protection against overfishing, habitat damage and pollution. “off-grade” which includes roe that is cut, broken, soft, or off-color. In general, that is best about Alaska salmon. In Alaska, the fish come first! high-grade sujiko usually follow these guidelines: • Eggs are large in size for the species Alaska salmon roe is a wild, natural product high in lean Unlike fish stocks in other parts of the world, no Alaska • Color is bright and uniform throughout salmon stocks are threatened or endangered. For this reason, the sac protein and omega-3 fatty acids. -

ANALYSIS / APPROACH / SOURCE / STRATEGY: GENERAL STUDIES PRE 2020 PAPER - TEAM VISION IAS Observations on CSP 2020

... Inspiring Innovation VISION IAS™ www.visionias.in www.visionias.wordpress.com “The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them." - Albert Einstein ANALYSIS / APPROACH / SOURCE / STRATEGY: GENERAL STUDIES PRE 2020 PAPER - TEAM VISION IAS Observations on CSP 2020 • This year the paper appeared to be on the tougher side and the options framed were confusing. • The static portions like History, Polity, Geography, Economics, etc. as expected were given due weightage. • Questions in almost all the subjects ranged from easy to medium to difficult level. Few unconventional questions were also seen. This year many questions were agriculture related which were asked from geography, environment and economics perspective. • Few questions asked by UPSC, although inspired by current affairs, required overall general awareness. For instance the questions on Indian elephants, cyber insurance, G-20, Siachen glacier, etc. • Polity questions demanded deeper understanding of the Constitution and its provisions. The options in polity questions were close but very easy basic fundamental questions like DPSP, Right to Equality, etc were asked from regular sources like Laxmikanth. Few Questions covering the governance aspect like Aadhar, Legal Services, etc were also given weightage. • In the History section, Ancient India questions were given more weightage unlike in the previous years, and their difficulty level was also high. Art & Culture and Medieval Indian history also had tough questions. However, the modern history section was of moderate level difficulty overall. • Environment questions unlike previous years did not focus on International climate initiatives and bodies. This year focus lay on environmental issues, application of technology and related concepts like benzene pollution, steel slag, biochar, etc. -

COLOR GELS Blue Violet PERMANENT CONDITIONING HAIRCOLOR

FASHION GELS NO BACKGROUND COLOR FASHION GELS BLONDE SERIES B V COLOR GELS Blue Violet PERMANENT CONDITIONING HAIRCOLOR LEVEL & GREEN NATURAL NATURAL ASH NATUR AL* GOLD BEIGE NATURAL WARM* NATURAL GOLD WARM GOLD* COPPER BROWN* RUBY BROWN* RED/ORANGE RED RED/VIOLET DESCRIPTION CLEAR TONE: Yellow/Green TONE: Corrective Tone TONE: Blue/Violet TONE: Gold/Beige TONE: Natural Level Tone TONE: Gold TONE: Yellow/Orange TONE: Orange TONE: Red/Violet TONE: Red/Orange TONE: Red TONE: Red/Violet BLACK TO GRAY BROWN TO TAN BACKGROUND COLOR NO BACKGROUND COLOR CLEAR BACKGROUND COLOR 10 ULTRA PALE BLONDE 10NA 10N 10NW 10NG Silk Crème Latté Macadamia Honey Nut 9 VERY LIGHT BLONDE 9NA 9N 9GB 9NW Platinum Ice Café au Lait Champagne Irish Creme 8 LIGHT BLONDE 8NA 8N 8NW 8NG 8WG Mojave Sesame Safari Sunflower Golden Apricot 7 MEDIUM BLONDE 7NA 7N 7GB 7NW 7NG 7RO 7R Mirage Bamboo Praline Cream Chestnut Saffron Marigold Flame 6 DARK BLONDE 6GN 6NA 6N 6NW 6NG 6WG 6CB 6RO 6R Moss Moroccan Suede Brandy St. Tropez Mango Cognac Bonfire Rocket Fire Sand 5 LIGHT BROWN 5NA 5N 5GB 5NW 5NG 5CB 5RB 5RO 5RV Walnut Coffee Bean Truffle Cappuccino Caramel Sandalwood Manzanita Paprika Scarlett 4 MEDIUM BROWN 4NA 4N 4NW 4NG 4WG 4CB 4R 4RV Chicory Hazelnut Maple Pecan Sun Tea Clove Lava Cabernet 3 DARK BROWN 3N 3NW 3RB Espresso Mocha Java Mahogany 2 DARKEST BROWN 2NW Chocolate 1 CLEAR BLACK *Superior Gray Coverage Family 1NW Midnight COLOR GELS LEVEL SYSTEM CHART MIXING RATIO COLOR GELS LEVELS USAGE MINUTES OFF-SCALP/ SPECIAL (COLOR : DEVELOPER) DEVELOPER OF LIFT HEAT OPTION INSTRUCTIONS LEVEL DESCRIPTION UNDERTONE CORRECTIVE TONE 10 volume Up to 1 Minimal Lift 20 STEM 10 Ultra Pale Blonde Pale Yellow Violet Standard Lift/ 20 volume Up to 2 30 Refer to the “Guidelines for 9 Very Light Blonde Yellow Violet Gray Coverage SY COLOR GELS Mix 1:1 Do not use heat. -

Iasbaba.Com History Compilation-Prelims

IASbaba.com History Compilation-Prelims 1. In British India, what is ‘Dastak’ known for? 1. A permit exempting European traders, mostly of the British East India Company, from paying customs or transit duties on their private trade. 2. A permit regulating internal trade, mostly for Indian traders. 3. Fee charged by Indian rulers from European Traders when they trade into their territory 4. Fee charged by British government for the regulation of domestic trade. Solution: 1 Explanation: Dastak, in 18th-century Bengal, a permit exempting European traders, mostly of the British East India Company, from paying customs or transit duties on their private trade. The name came from the Persian word for “pass.” The practice was introduced by Robert Clive, one of the creators of British power in India, when he had Mir Jaʿfar installed as nawab of Bengal in 1757. The attempt of Mir Jaʿfar’s successor, Mir Qāsim, to annul the use of dastaks led to his overthrow in 1763–64 and the exercise of overt control of Bengal by the British. Free dastaks for private trade were finally abolished by Warren Hastings, governor of Bengal (1775). The system put the Indian trader at a grave disadvantage in competing with the European and was an important factor in the impoverishment of Bengal under early British rule. Iasbaba.com Page 1 IASbaba.com 2. Consider the following statements with respect to administration of Maratha and Mughal Empires 1. The revenue system of Marathas was progressive unlike Mughals who were mainly interested in raising revenues from the helpless peasantry. 2. -

The Condition of the Workers in Indigo Plantation Work During the Period

International Journal of Applied Research 2017; 3(6): 219-223 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 The condition of the workers in indigo plantation Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2017; 3(6): 219-223 work during the period between 1850 and 1895 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 12-04-2017 Accepted: 13-05-2017 Sushant Kumar Singh Sushant Kumar Singh PhD candidate Centre for Abstract Economic Studies and This paper is mainly enquired into the socio-economic plight of workers in Indigo plantation Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru agricultural activities under the British colonial rule in India, lower Bengal. An attempt has been made University, New Delhi, India to analyse the interaction of the political, economic and social changes during this turbulent period and studies the intricacies of the indigo cultivation and illustrates how the technicalities created conflicts between the ‘Ryots’ and the planters. Paper firmly found the peasant rising grew in militancy and organisation; it also underwent changes in “leadership and alignment” This was hardly an anti-British movement in character. The peasants associated indigo with swindle and oppression – and that was it. Keywords: indigo plantation, British colonial rule, exploitation, peasant rising, lower Bengal Introduction “The story of the Indigo Industry is more interesting historically and more pathetically instructive that that of almost any other Indian agricultural or industrial substance [1].” Keeping the sentiments of the preceding words intact becomes seemingly important when one seeks to understand and associate with the turbulent history of the blue dye. The story of the incessant greed and atrocity of the indigo planters that roused thousands of indigo peasants from meek submissiveness to the sternest defiance imaginable is indeed an interesting one. -

148 Colour Chart

148 colour chart IVORY PRIMROSE BUTTERCUP SOFT LIME TULIP YELLOW LEMON YELLOW CANARY SUNFLOWER ALMOND BLUSH SAFFRON Y418 Y919 Y417 Y828 Y337 Y747 Y657 Y367 Y156 O819 O729 O739 VANILLA PASTEL YELLOW MUSTARD OATMEAL APRICOT HONEYCOMB GOLD AMBER PUMPKIN GINGER BRIGHT ORANGE MANDARIN O929 O949 O948 O628 O538 O547 O555 O567 O467 O136 O177 O277 ORANGE SPICE BURNT ORANGE SATIN DUSKY PINK PUTTY SUNKISSED PINK CORAL SOFT PEACH PEACH MANGO PASTEL PINK R866 O346 R946 Y129 O518 O618 O228 R937 O138 O148 O248 R738 COCKTAIL PINK SALMON PINK ANTIQUE PINK LIPSTICK RED RED BERRY RED RUBY POPPY CRIMSON CARDINAL RED BURGUNDY MAROON R438 R547 R346 R576 R666 R665 R455 R565 R445 R244 R424 M544 PALE PINK BABY PINK ROSE PINK CERISE HOT PINK MAGENTA CARMINE DUSKY ROSE BLOSSOM PINK CARNATION FUCHSIA PINK SLATE R519 R228 M727 M647 R365 M865 R156 R327 M428 M328 M137 V715 AMETHYST PURPLE MULBERRY PLUM AUBERGINE LAVENDER ORCHID LILAC BLUEBELL VIOLET PRUSSIAN BLUE PEARL V626 V546 V865 V735 V524 V518 V528 V327 V127 V245 V464 B528 CORNFLOWER COBALT BLUE CHINA BLUE MIDNIGHT BLUE INDIGO BLUE ROYAL BLUE TRUE BLUE AZURE SKY BLUE CYAN PASTEL BLUE POWDER BLUE B617 B637 B736 B624 V234 V264 B555 B346 B137 C847 C719 B119 ARCTIC BLUE DENIM BLUE AEGEAN FRENCH NAVY COOL AQUA DUCK EGG TURQUOISE MARINE PETROL BLUE HOLLY PINE EMERALD B138 C917 B146 B445 C429 C528 C247 C446 C824 G724 G635 G657 GREEN LUSH GREEN PASTEL GREEN SOFT GREEN MINT GREEN GRASS FOREST GREEN TEA GREEN GREY GREEN MEADOW GREEN APPLE LEAF GREEN G847 G756 G829 G817 G637 G457 G356 G619 G917 G339 G338 G258 BRIGHT GREEN -

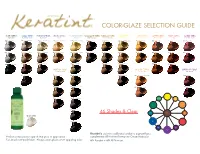

Color-Glaze Selection Guide

COLOR-GLAZE SELECTION GUIDE SLATE SERIES COOL SERIES NATURAL PEARL BEIGE SERIES NATURAL SERIES CHOCOLATE SERIES TOBACCO SERIES GOLD SERIES SUN SERIES COPPER SERIES RUBY SERIES SCARLET SERIES BLUE/OLIVE BLUE/BLUE VIOLET BLUE VIOLET VIOLET PRIMARY WARM NATURAL YELLOW NATURAL YELLOW GOLD YELLOW ORANGE RED ORANGE RED RED / RED VIOLET 8CS Light Slate 10C Very Light Cool Blonde 10P Very Light Pearl Blonde 10B Very Light Beige Blonde 10N Very Light Natural Blonde 6CH Chocolate 7T Light Tobacco 10G Very Light Gold Blonde 8S Brilliant Sun Poppy 8RC Brilliant Copper 8R Brilliant Ruby Red 8RS Brilliant Scarlet 6CS Slate 8C Medium Cool Blonde 8P Medium Pearl Blonde 8B Medium Beige Blonde 8N Medium Natural Blonde 4CH Dark Chocolate 6T Tobacco 8G Gold Blonde 6S Sun Poppy 6RC Copper 6R Ruby Red 6RS Scarlet 6C Light Cool Brown 6P Light Pearl Brown 7N Deep Natural Blonde 5T Medium Tobacco 6G Light Gold Brown 4RC Dark Copper 2CS Cool Dark Slate 4R Dark Ruby Red MOCHA SERIES INTENSE COPPER BURGUNDY SERIES NATURAL VIOLET ORANGE RED RED VIOLET 4C Dark Cool Brown 7M Light Ice Mocha 6N Light Natural Brown 4G Dark Gold Brown 8IC Brilliant Intense Copper Blonde 6RB Burgundy 6M Ice Mocha 5N Medium Natural Brown 6IC Intense Copper Blonde 4RB Dark Burgundy Yellow 5M Medium Ice Mocha 4N Dark Natural Brown Yellow Green Yellow Orange Orange Green 3N Ebony Brown Blue Natural Red 46 Shades & Clear Green Orange Clear 0/00 Blue 1N Blue Black Red Blue Red Violet Violet Violet Keratint’s exclusive calibrated oxidative pigment base Perform predisposition (patch test) prior to application.