COR 2014 4052 FINDING INTO DEATH with INQUEST Form 37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Newsletter

Telephone: 5457 2284 Fax 5457 2417 Walk to School and Walk and Talk Email: [email protected] Tomorrow is our last Walking School Bus. Website: www.murrabitps.vic.edu.au It has been a great program which has engaged the students throughout the NEWSLETTER month of October. - 31st October, 2019 School Values: • Respect • Honesty • Teamwork • Learning • Persistence Mangoes Murrabit Group School respectfully acknowledges A big thank you to our wonderful Parents the traditional custodians of the land. and Friends for the fantastic Mango Drive. We pay respect to their ongoing living culture. Also to the many people who supported the Mango Drive by making purchases. This Dates to Remember : has been a great fundraiser for the school 5th Nov . Melbourne Cup Holiday which will result in an amazing chicken 6th Nov. School Council shed next year. It is great to know that 13 th Nov Prep Transition 9 -1:45 children are at the centre of our efforts. Hello Everybody , School Council Camps and Excursions School Council takes place next Yesterday we went to see Charlie and the Wednesday 6th November at 6pm. I look Chocolate Factory. Thank you to our forward to catching up with School Council parents who assisted on the day, they members for our second last meeting of the being Sara McNeil, Donna Thomson, year. Nicole Hein, Michelle Mathews, carly Ettershank, Karen Maher, Erin Hein, Ang Remembrance Day Morton, Elissa Keath, Jo Danson, Jodie Next Wednesday, the 6 th November, Mr Hartley and Chris Murray. The children Max Molloy from the RSL will be speaking thoroughly enjoyed the day. -

Appendix 1 Citations for Proposed New Precinct Heritage Overlays

Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review Appendix 1 Citations for proposed new precinct heritage overlays © Biosis 2017 – Leaders in Ecology and Heritage Consulting 183 Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review A1.1 City Road industrial and warehouse precinct Place Name: City Road industrial and warehouse Heritage Overlay: HO precinct Address: City Road, Queens Bridge Street, Southbank Constructed: 1880s-1930s Heritage precinct overlay: Proposed Integrity: Good Heritage overlay(s): Proposed Condition: Good Proposed grading: Significant precinct Significance: Historic, Aesthetic, Social Thematic Victoria’s framework of historical 5.3 – Marketing and retailing, 5.2 – Developing a Context: themes manufacturing capacity City of Melbourne thematic 5.3 – Developing a large, city-based economy, 5.5 – Building a environmental history manufacturing industry History The south bank of the Yarra River developed as a shipping and commercial area from the 1840s, although only scattered buildings existed prior to the later 19th century. Queens Bridge Street (originally called Moray Street North, along with City Road, provided the main access into South and Port Melbourne from the city when the only bridges available for foot and wheel traffic were the Princes the Falls bridges. The Kearney map of 1855 shows land north of City Road (then Sandridge Road) as poorly-drained and avoided on account of its flood-prone nature. To the immediate south was Emerald Hill. The Port Melbourne railway crossed the river at The Falls and ran north of City Road. By the time of Commander Cox’s 1866 map, some industrial premises were located on the Yarra River bank and walking tracks connected them with the Sandridge Road and Emerald Hill. -

Murrabit Outing

Inaugural Member Society of the Genealogical Society of Vic. c/- Swan Hill Regional Library, 53-67 Campbell Street, PO Box 1232, Swan Hill, Vic., 3585 Telephone (03) 50362472 Web Page: http://home.vicnet.net.au/~shghs/ Email: [email protected] ISSN 1036-1006 No. A17395X ABN 42 840 859 237 MURRABIT OUTING On the 13th of May, seven of our members enjoyed an historical tour of Murrabit as guests of the Kerang group. First we saw a “Bing Bong” house which was a relic of the closer settlement commission of the early 1900’s. These houses were very cheaply built and were clad inside and out with galvanized iron sheeting which went bing bong as it expanded and contracted in the sun. We then crossed the river and visited the Gonn Crossing location, en route the original Gurnett Homestead was pointed out to us. We had lunch at the Murrabit hall where the history and construction of the “Bing Bong” houses was explained and Ian McDonald spoke of the history of the district and his families involvement in local history. At Gonn station we saw the old station burial plot where there are headstones for John Capel, his horse and dog but none for his cook or the station hands buried there. Ian showed us the bridge from Gonn to Campbells Island which was built after Ian and his brother sank a punt load of sheep they were trying to bring back from the island. He then showed us a number of features and told us stories of life on the station. -

Kerang Cohuna Koondrook

KERANG Victoria’sCOHUNA Nature Based Tourism Destination... KOONDROOK Visitor Guide Victoria’s Nature Based Tourism Destination... Visitor Guide THE REGION... to Mildura Kyalite to Hay Kyalite State Letwa NEW Forest State Forest Lake SOUTH Coonaroop Piangil Tooleybuc WALES ➘ to Adelaide 506km Moulamein Lake Poon Boon Koraleigh Edward River Nyah to Deniliquin 42km 87km Werai Murray Downs Lake Niemur River State Forest Swan Hill Murray Downs d Donald R / l il Wakool River H Murray River an w S Campbells to Donald Island State Wakool 115km Lake Boga Forest Lake Tutchewop Loddon River Murrabit Lake Whymoul VICTORIA Kangaroo Lake Lake Lake Lalbert Lake Charm Cullen M Third Barham u r Lake The ra Koondrook y V Marsh a Middle to Deniliquin Lalbert lle Lake Duck y Gunbower 87km Sandhill H Reedy State Forest Lake w 26km Lake Lake Lake Bael Lake y Bael Elizabeth Koondrook to State Forest Kerang 23km Moama d R 33km g an Cohuna er K Gunbower t r Johnson y National Park o w Swamp o H Quambatook B G y u n e l l b a o w V e r Hird n C o Swamp Leitchville re d e d k o L Kow Gunbower to Melbourne Avoca River Swamp via Bendigo Lake 285km Meran to Echuca Mt Hope Gateway to Gannawarra Visitor Centre 90 King George Street, Cohuna. Phone: 03 5456 2047 Web: www.visitkck.com.au For further information contact: Gannawarra Shire Council - 47 Victoria St, PO Box 287, KERANG VIC 3579. Phone: (03) 5450 9333 2 www.visitkck.com.au VISITOR GUIDE CONTENTS WELCOME Our towns ______________________________4 Our lakes and rivers _______________________9 Welcome to the Gannawarra Shire! Boat ramps and launching places _____________14 Just a three hour drive from Melbourne and you can RV free camping and dump points ____________14 experience a region loaded with natural features, Our Industry Manufacturing _________________________ rivers, lakes, wetlands and forests. -

Wakool Bowlingclub

No: 4204 Print Post: 100002834 Thursday, February 11, 2021 Recommended Price $2.00 Inc. GST Pages: 20 Fully independent, local and yours, since 1909 thebridgenews.com.au MAKING A A CHAT SPLASH WITH... PAGE 4 PART 2: PAGE 9 WILL YOU HEED THE CALL? Join the Team – PAGE 7 2 – Thursday, February 11, 2021 | The Koondrook–Barham Bridge Letters to the Editor e: [email protected] ~ ESTABLISHED 1909 ~ PO Box 138, Barham, NSW 2732 THE KOONDROOK & BARHAM Dear Editor, generational river families, BRIDGE NEWSPAPER I looked at the calendar, that’s what it will learn. Contributors, please note: saw it was the first day of Instead, it comes up with the month and thought it these pie-eyed ideas to jus- The Koondrook-Barham Bridge welcomes any member of the public or organisation to respond to articles or SHOP 2, 5 - 9 MELLOOL STREET, must be April Fool’s Day. tify the failing Basin Plan, current affairs in the “Letters to the Editor” section: The Koondrook–Barham Bridge is your voice! PO BOX 138, BARHAM NSW 2732 That was my immedi- which was built on false Just remember that all contributors of articles or letters must have your name and current address clearly ate reaction to claims an- assumptions and poor sci- indicated at the time of submission. You can remain anonymous or go under a pseudonym for publication. PHONE: 03 5453 2057 nounced on Monday, Feb- ence. The MDBA tells us, Inform us on your submission if you wish to do so. Your details will never be disclosed. -

Financial Impacts on the Tourism and Events Sector in the Gannawarra As a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic

LC EIC Inquiry into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and events sectors Submission 051 Financial Impacts on the tourism and events sector in the Gannawarra as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: Domestic Overnight Visitation in the Gannawarra is estimated at $42.2M. Murray Regional Tourism (MRT) research for the Swan Hill region (which includes Gannawarra Shire) shows a decline of 26.2%. This equates to a loss of approximately $11M. A Murray Regional Tourism report assumes “a loss of one job per $100,000 visitor expenditure loss”. The estimated loss of $11M for the Swan Hill region equates to a loss of around 110 jobs. The Cohuna Waterfront Holiday Park reported a 40% reduction in the occupancy rate during the pandemic and this was similar across many of the accommodation providers. A number of the accommodation and hospitality providers operating in small regional towns were not eligible for business support packages and received no financial assistance from COVID-19 initiatives. A large number of events were cancelled across the Gannawarra because of COVID- 19 restrictions. Cancellation of these events reflects a loss of around $850,000. Ski Racing Victoria hosts four Point Score events annually at Lake Charm. REMPLAN analysis shows these events to be worth $38,000, resulting in a loss of $152,000. Community groups have been significantly impacted as a result of COVID-19 with limited ability to raise funds. Groups have had to use limited cash reserves to continue to operate. Without events, many groups have limited capacity to contribute to their many community based projects. -

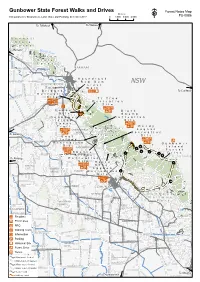

Gunbower State Forest Walks and Drives Forest Notes Map Meters FS-0086 © Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning

# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # Gunbower State Forest Walks and Drives Forest Notes Map Meters FS-0086 © Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. December 2017 0 1,500 3,000 4,500 F To Tullakool To Wakool # # ## # # # # B e n w e l l # S t a t e # # # F o r e s t # # To Murrabit Murray River KOONDROOK-MURRABIT ROAD # G u t t r a m # # S t a t e # F o r e s t # # BARHAM WESTBLADE ROAD CULFEARNE # K o o n d r o o k MCKENZIE ROAD PINES ROAD R e d G u m HINKSON ROAD KOONDROOK F o r e s t NSW # T w i n W a l k # # B r i d g e s 4gd To Caldwell R e c r e a t i o n # PARKER ROAD S i t e TEALVFo ! T i T r e e POINTmM2 R e c r e a t i o n S i t e ¡ VFo ! # C a n o e ! Mm B l a c k S i t e S w a m p KERANG-KOONDROOK ROAD G u n b o w e r R e c r e a t i o n I s l a n d S i t e C a n o e VFo ! Mm R e e d y YEOBURN CRAIG ROAD T r a i l VFo GANNAWARRA G u n b o w e r L a g o o n Mm NORTH S t a t e 6 R e c r e a t i o n To Kerang KOROOP ROAD G o a t ! F o r e s t S i t e VFo I s l a n d u # KOROOP Mm SMITH ROAD R e c r e a t i o n ! ! 9 G u n b o w e r S i t e 5 KENNY ROAD GANNAWARRA I s l a n d VFo1 3 F o r e s t 4 6 Mm S p e n c e 2 D r i v e BOYD ROAD SAFE ROAD ! 7 PHILLIPS ROAD B r i d g e 8 Log Landing # To Kerang R e c r e a t i o n # S i t e VFo H o r s e 9 KERANG S h o e FAIRLEY ROAD FAIRLEY EAST MILNES Mm L a g o o n BRIDGE CULLEN R e c r e a t i o n 1 SCHWENCKESROAD S i t e VFo # Mm COHUNA ISLAND ROAD 10 TROY ROAD MEAD COHUNA MCMILLANS G u n b o w e r CHUGGS ROAD COHUNA-MCMILLANS ROAD N a t i o n a l MEAD ROADMEAD MACORNA P -

Torrumbarry Delivery Share Trading Zone

Torrumbarry Delivery Share Trading Zone Little Murray Riv e r M e r ra FISH POINT n C r e e LAKE BOGA k BENJEROOP WINLATON TRESCO MURRABIT WEST TRESCO WEST GONN CROSSING Merribi MURRABIT t C r Mu e r CAMPBELLS ISLAND e r k a b it R MYSTIC PARK iv e KERANG LAKES r MYALL M W ur ak ol River ray o R iv e r LAKE CHARM CAPELS CROSSING KOONDROOK WESTBY B a FAIRLEY rr YEOBURN C re ek KORRAK KORRAK SANDHILL LAKE PYRAMID CREEK r KERANG e iv KOROOP a R Avoc BUDGERUM EAST KERANG EAST SOUTH KERANG COHUNA NORMANVILLE DINGWALL r ive R n o d MACORNA NORTH d LANGVILLE o Gun L TRAGOWEL b ow e r C Pyr re am HORFIELD e LAKE MERAN id k C r e LEITCHVILLE MEERING WEST e APPIN k APPIN SOUTH MACORNA MINCHA WEST GUNBOWER eek LEAGHUR Cr ck GREDGWIN lo ul CANARY ISLAND B MINCHA LODDON VALE M PATHO o u BARRAPORT n t H o p BALD ROCK e PATHO WEST C MINMINDIE r GLADFIELD e e CANARY ISLAND SOUTH PYRAMID HILL k CATUMNAL YANDO TERRICK TERRICK k SYLVATERRE e YARRAWALLA re BOORT C o DURHAM OX ig d BOORT EAST n e B MOLOGA SCALE AT A4 1:395,000 03.75 7.5 15 Legend © km Town - Major Freeway Semi-Major Road Waterway The content of this product is provided for information purposes only. IR95855 No claim is made as to the accuracy of authenticity of the content of the Town - Minor Highway Minor Road Reservoir product. -

GRFNL Initial Senior Interleague Training Squad

Golden Rivers Football League Inc. Worksafe AFL Victoria Country All correspondence AFL CM Sheridan Harrop PO Box 376 Swan Hill 3585 | Mob: 0408 807 325 | email: [email protected] Memorandum From: Sheridan Harrop, AFL Central Murray Date: Friday, 5 April 2019 Re: GRFNL Interleague To: Senior GRFNL Coaches CC: Club Secretary & President The Central Rivers Board would like to congratulate the following players on being selected for the initial GRFNL Senior Interleague Training squad. Name Club Name Club Name Club Angus McSweyn Hay Andrew Oberdorfer Nullawil Arnold Kirby Ultima David Fevaleaki Hay Daniel Watts Nullawil Brodie Bennett Ultima Hugh McLean Hay Dean Smith Nullawil Jayden Keil Ultima Jackson Ferguson Hay Grant Ford Nullawil Josh Dwyer Ultima Jock Crigthon Hay Jordan Humphreys Nullawil Jye Purtill Ultima Jake McIntosh Macorna Mitchell Farmer Nullawil Kyle Brasser Ultima Joshua Cameron Macorna Phillip Lobb Nullawil Martyn Cooper Ultima Kansas Varker Macorna Rylee Smith Nullawil Samuel Hinton Ultima Shaun Haffenden Macorna Ash Davis Quambatook Thomas Bull Ultima Wayne Wishart Macorna Christopher Kendall Quambatook Clinton Cummins Wandella Noah O'Flaherty Macorna Dylan Pascoe Quambatook Cody Schepers Wandella Austin Mertz Moulamein Dylan Wright Quambatook Cooper Condely Wandella Ben Booth Moulamein Gregor Knight Quambatook Daniel Baker Wandella Bradley Williamson Moulamein Jack Baker Quambatook Dillan Treacy Wandella Michael Morson Moulamein James Blackwell Quambatook Dylan McGrath Wandella Thomas Isma Moulamein Ricky Wild Quambatook -

Appendix 1: List of Assessed Landfills

APPENDIX 1: LIST OF ASSESSED LANDFILLS Municipality Site address GREATER BENDIGO CITY COUNCIL UPPER CALIFORNIA GULLY RD, EAGLEHAWK VIC 3556 MILDURA RURAL CITY COUNCIL ONTARIO AV, MILDURA VIC 3500 CARDINIA SHIRE COUNCIL FIVE MILE RD, NAR NAR GOON VIC 3812 BRIMBANK CITY COUNCIL CNR GEELONG RD & MCDONALD RD, BROOKLYN VIC 3012 LODDON SHIRE COUNCIL OFF GODFREY ST, WEDDERBURN VIC 3518 GREATER SHEPPARTON CITY COUNCIL RIVER RD, KIALLA VIC 3631 LATROBE CITY COUNCIL PARISH OF MIRBOO EAST C/A 140A, MIRBOO EAST VIC 3870 BASS COAST SHIRE COUNCIL GRANTVILLE GRAVEL RESERVE, CNR BASS HWY & STANLEY RD, GRANTVILLE VIC 3984 BASS COAST SHIRE COUNCIL PARISH OF PHILLIP ISLAND PT C/A 95A, PHILLIP ISLAND VIC 3922 MOIRA SHIRE COUNCIL PARISH OF KATUNGA C/A 14 SECT D NARING RD, NUMURKAH VIC 3636 NILLUMBIK SHIRE COUNCIL NILLUMBIK SHIRE COUNCIL DEPOT, YAN YEAN RD, YARRAMBAT VIC 3091 BAW BAW SHIRE COUNCIL HARD RUBBISH DUMP OPEN CUT YALLOURN WORKS AREA, YALLOURN NORTH VIC 3825 WHITTLESEA CITY COUNCIL 470 COOPER ST, EPPING VIC 3076 KNOX CITY COUNCIL CNR HIGH ST & CATHIES LA, WANTIRNA SOUTH VIC 3152 WHITEHORSE CITY COUNCIL 14 FEDERATION ST, BOX HILL VIC 3128 HINDMARSH SHIRE COUNCIL OFF RAINBOW-NHILL RD, RAINBOW VIC 3424 HOBSONS BAY CITY COUNCIL MCARTHURS RD, ALTONA VIC 3018 WANGARATTA RURAL CITY COUNCIL COLEMAN RD, BOWSER VIC 3678 TOWONG SHIRE COUNCIL CA21B, Section A 1877 Katandra Road, Yabba North, 3646 GREATER DANDENONG CITY COUNCIL CLARKE RD, SPRINGVALE SOUTH VIC 3172 GANNAWARRA SHIRE COUNCIL PT OF C/A 55 DENYER RD, KERANG VIC 3579 SOUTH GIPPSLAND SHIRE COUNCIL KOONWARRA -

GANNAWARRA SHIRE D TITTYBONG K TOWANINNY Cree

GANNAWARRA SHIRE TOWN AND RURAL DISTRICT Mu NAMES AND BOUNDARIES rr ay BENJEROOP L o d d o n MURRABIT M U Lake GONN R WEST R A Tutchewop CROSSING Y SWAN HILL V A L Lake L E William Y K O O N Lake D MURRABIT R Kelly O O K D R MYSTIC PARK M U R Kangaroo AB D IT MEATIAN R Lake LAKE CHARM R iv L e L I Lake r H N A Charm CAPELS MYALL W S Racecourse CROSSING D Lake L A BEAUCHAMP N RD O D Lake KOONDROOK D Cullen WESTBY O N A LALBERT D L R D S R W REEDY iver A N BAEL BAEL LAKE H I L Lake L T Lookout I B Lake A R Bael U TEAL POINT FAIRLEY M Bael CO HU NA L Lake K a NG OO l A R b R ND r Elizabeth KE O M e O e K u r v r t i ray R Sand Hill G GANNAWK ARRA N O A O H R Lake N W E K D WANDELLA Y KERANG R O R O D RD K KOROOP CANNIE SANDHILL LAKE TITTYBONG MURRAY ca VALLEY vo D A BUDGERUM R R D EAST r e L CULLEN COHUUNA v O i D KERANG EAST MILNES R D O N BRIDGE HWY C K OO r AT e MB NORMANVILLE e UA PINE VIEW k Q G N V M A DINGWALL A U R DUMOSA QUAMBATOOK E L Johnson R RD K L C R E O A Y Swamp MEAD Y H DALTONS U BURKES N V A A L L E BRIDGE Y BRIDGE LE I T QUAMBATOOK MACORNA C H TRAGOWEL McMILLANS V I NORTH L LE UP G R N KEELY A E R Hird E E W K Swamp TOWANINNY EE Lake W Meran R T APPIN i BULOKE R v O e MEERING O n HORFIELD B o r d PYRAMID HILL PYRAMID WEST d LEITCHVILLE o LEITCHVILLE LAKE MERAN L r RD e v i R H W Y APPIN SOUTH RD H MINCHA WEST OAKVALE W MACORNA Y Kow CAMPASPE NINYEUNOOK GREDGWIN LODDON Swamp a Prepared by Customised Mapping, c o v Spatial information Infrastructure, Ballarat A LEGEND 0 10 20 TOWN AND RURAL Version 4.1a kilometres KERANG DISTRICT BOUNDARIES October, 2007 © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2007 (defined as localities in Govt. -

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator's Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide 1 March 2019 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Approved Routes and Travel Restrictions ................................................................................................................ 3 1. Part 1 NSW Urban Zone ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Travel Restrictions in the NSW Urban Zone ................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1. Clearway and transit lane travel ............................................................................................................. 3 1.1.2. Peak hour travel ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3. Peak hour travel – Newcastle Outer Zone ............................................................................................... 4 1.1.4. Night travel ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1.5. Sundays and state-wide public holidays ................................................................................................. 5 1.1.6. Public