Map 69 Damascus-Caesarea Compiled by J.P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maps of First Century Palestine

Fellowship Home Page The Map of First Century Palestine Index to Geographic Place Names Urantia Papers' First Century Palestine The grid upon which the map is constructed is the standard MR grid system used in many archaeological reports and other descriptive literature of the region, such as the Anchor Bible Dictionary. In this grid system, the first three digits designate a position on the north-south axis of the map while the second three digits designate a position on the east-west axis, the intersection of the two lines being the location of the index item on the map. On the map itself, the north-south coordinates read vertically while the east-west coordinates read horizontally. The map shows the location of all the villages and towns mentioned in Part IV of The Urantia Book. The index lists these as well as other towns and villages which were known to have existed at the time of Jesus, but which do not appear on the map. Look up the name of any first-century place location. Letters below are linked to corresponding sections of the index: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | Z | A ABEL 236-183 ABELA 139-211 ABELIM 248-167 ABILA 232-234 ACHZIB; ECDIPPA 271-159 ACRABETA 170-182 ADAM 167-202 ADAMAH 238-193 ADIDA 152-145 ADORAIM; DURA 101-153 AENON 138-203 AGRIPPINA? 192-218 AILABO 249-187 AIN 236-212 ALEXANDRIUM 166-193 ALMA 273-196 AMATHUS 183-208 AMMATHUS 240-202 AMMUDIM 247-188 AMUDIYYA 266-216 ANABTAH 191-162 ANATHOTH 135-174 ANIM 84-156 ANTHEDON 105- 98 ANTIPATRIS 168-143 ANUATHU -

Giant Building Sites in Antiquity the Culture, Politics and Technology of Monumental Architecture

ARCHAEOLOGY WORLDWIDE 2 • 2013 Magazine of the German Archaeological Institute Archaeology Worldwide – Volume two – Berlin, October – DAI 2013 TITLE STORY GIANT BUILDING SITES IN ANTIQUITY The culture, politics and technology of monumental architecture CULTURAL HERITAGE PORTRAIT INTERVIEW Turkey – Restoration work in the Brita Wagener – German IT construction sites in the Red Hall in Bergama ambassador in Baghdad archaeological sciences ARCHAEOLOGY WORLDWIDE Locations featured in this issue Turkey, Bergama. Cultural Heritage, page 12 Iraq, Uruk/Warka. Title Story, page 41, 46 Solomon Islands, West Pacific. Everyday Archaeology, page 18 Ukraine, Talianki. Title Story, page 48 Germany, Munich. Location, page 66 Italy, Rome/Castel Gandolfo. Title Story, page 52 Russia, North Caucasus. Landscape, page 26 Israel, Jerusalem. Title Story, page 55 Greece, Athens. The Object, page 30 Greece, Tiryns. Report, page 60 Berlin, Head Office of the German Archaeological Institute Lebanon, Baalbek. Title Story, page 36 COVER PHOTO At Baalbek, 45 million year old, weather- ing-resistant nummulitic limestone, which lies in thick shelves in the earth in this lo- cality, gained fame in monumental archi- tecture. It was just good enough for Jupiter and his gigantic temple. For columns that were 18 metres high the architects needed no more than three drums each; they measured 2.2 metres in diameter. The tem- ple podium is constructed of colossal lime- stone blocks that fit precisely together. The upper layer of the podium, today called the "trilithon", was never completed. Weighing up to 1,000 tons, these blocks are the big- gest known megaliths in history. DITORIAL E EDITORIAL DEAR READERS, You don't always need a crane or a bull- "only" the business of the master-builders dozer to do archaeological fieldwork. -

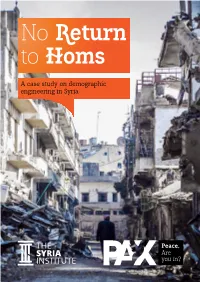

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Sociology and Anthropology 1998 Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle '98 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation VanSickle '98, Sarah, "Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel" (1998). Honors Projects. 19. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj/19 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by Faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Trade and Commerce At Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle 1998 Honors Research Dr. Dennis E. Groh, Advisor I Introduction Trade patterns in the Near East are the subject of conflicting interpretations. Researchers debate whether Galilean cities utilized trade routes along the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean or were self-sufficient, with little access to trade. An analysis of material culture found at specific sites can most efficiently determine the extent of trade in the region. If commerce is extensive, a significant assemblage of foreign goods will be found; an overwhelming majority of provincial artifacts will suggest minimal trade. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The semitic background of the synoptics Bussby, Frederick How to cite: Bussby, Frederick (1947) The semitic background of the synoptics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9523/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE SEMITIC BACKGROUND OF THE SYNOPTICS Frederick Bussby A thesis submitted for the degree of B.I>. in the University of Durham July 1947 CONTESTS Page Bibliography 4 Abbreviations 10 Introduction 12 Historical attempts to trace a semitio origin of the Gospels from Papias to Torrey 16 Semitio and Non-semitic - 18 MA EE Transliterations explained by Mark 22: Abba-Bart imaeus-Boane rges-Elo i Eloi lama sabachthani-Ephphatha-Golgotha Korban-Talitha cumi. Transliterations not explained by Mark 27 ' Amen-Beelzebub-Kollubis^Tard-Passover-Pharisee Rabfci-Rabboni-Sabbath-Prosabbath-Sadducee-Satan Place names in Mark 34 Bethany-Bethphage-Bethsaida (Sidon)-Capernaum Dalmanutha-Decapolis-Gerasa-Gethsemane-Magdala- Mazareth.Appendix: Cyrene-Dialect of Galilee A Greek a Syrophoenician-Jerusalem Personal names in Mark 43 Alphaeus-Barabbas-Joses-Judas Iscariot-Peter Translations and mis-translations in Mark 47 11.3;11.4;11.10;11.11;11.19;111.28;IV.4;IV.12 IV.29;V.16-17;VI.8;VII.3;VIII.33;IZ;18;IX.20; XII.40;XIV.72;XVI.8. -

A Christian's Map of the Holy Land

A CHRISTIAN'S MAP OF THE HOLY LAND Sidon N ia ic n e o Zarefath h P (Sarepta) n R E i I T U A y r t s i Mt. of Lebanon n i Mt. of Antilebanon Mt. M y Hermon ’ Beaufort n s a u b s s LEGEND e J A IJON a H Kal'at S Towns visited by Jesus as I L e o n Nain t e s Nimrud mentioned in the Gospels Caesarea I C Philippi (Banias, Paneas) Old Towns New Towns ABEL BETH DAN I MA’ACHA T Tyre A B a n Ruins Fortress/Castle I N i a s Lake Je KANAH Journeys of Jesus E s Pjlaia E u N s ’ Ancient Road HADDERY TYRE M O i REHOB n S (ROSH HANIKRA) A i KUNEITRA s Bar'am t r H y s u Towns visited by Jesus MISREPOTH in K Kedesh sc MAIM Ph a Sidon P oe Merom am n HAZOR D Tyre ic o U N ACHZIV ia BET HANOTH t Caesarea Philippi d a o Bethsaida Julias GISCALA HAROSH A R Capernaum an A om Tabgha E R G Magdala Shave ACHSAPH E SAFED Zion n Cana E L a Nazareth I RAMAH d r Nain L Chorazin o J Bethsaida Bethabara N Mt. of Beatitudes A Julias Shechem (Jacob’s Well) ACRE GOLAN Bethany (Mt. of Olives) PISE GENES VENISE AMALFI (Akko) G Capernaum A CABUL Bethany (Jordan) Tabgha Ephraim Jotapata (Heptapegon) Gergesa (Kursi) Jericho R 70 A.D. Magdala Jerusalem HAIFA 1187 Emmaus HIPPOS (Susita) Horns of Hittin Bethlehem K TIBERIAS R i Arbel APHEK s Gamala h Sea of o Atlit n TARICHAFA Galilee SEPPHORIS Castle pelerin Y a r m u k E Bet Tsippori Cana Shearim Yezreel Valley Mt. -

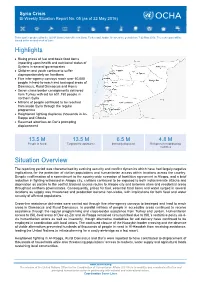

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Syria Refugee Response

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON, Bekaa & Baalbek-El Hermel Governorate Distribution of the Registered Syrian Refugees at the Cadastral Level As o f 3 0 Se p t e m b e r 2 0 2 0 Charbine El-Hermel BEKAA & Baalbek - El Hermel 49 Total No. of Household Registered 73,427 Total No. of Individuals Registered 340,600 Hermel 6,580 El Hermel Michaa Qaa Jouar Mrajhine Maqiye Qaa Ouadi Zighrine El-Khanzir 36 5 Hermel Deir Mar Jbab Maroun Baalbek 29 10 Qaa Baalbek 10,358 Qaa Baayoun 553 Ras Baalbek El Gharbi Ras Baalbek 44 Ouadi Faara Ras Baalbek Es-Sahel Ouadi 977 Faara Maaysra 4 El-Hermel 32 Halbata Ras Baalbek Ech-Charqi 1 Zabboud 116 Ouadi 63 Fekehe El-Aaoss 2,239 Kharayeb El-Hermel Harabta 16 Bajjaje Aain 63 7 Baalbek Sbouba 1,701 Nabha Nabi Ed-Damdoum Osmane 44 288 Aaynata Baalbek Laboue 34 1,525 Barqa Ram 29 Baalbek 5 Qarha Baalbek Moqraq Chaat Bechouat Aarsal 2,031 48 Riha 33,521 3 Yammoune 550 Deir Kneisset El-Ahmar Baalbek 3,381 28 Dar Btedaai Baalbak El-Ouassaa 166 30 Youmine 2,151 Maqne Chlifa Mazraat 260 beit 523 Bouday Mchaik Nahle 1,501 3 Iaat baalbek haouch 2,421 290 El-Dehab 42 Aadous Saaide 1,244 Hadath 1,406 Haouch Baalbek Jebaa Kfar Dane Haouche Tall Safiye Baalbek 656 375 Barada 12,722 478 466 Aamchki Taraiya Majdaloun 13 905 1,195 Douris Slouqi 3,210 Aain Hizzine Taibet Bourday Chmistar 361 Baalbek 160 2,284 515 Aain Es-Siyaa Chadoura Kfar Talia Bednayel 1,235 Dabach Haouch Baalbak Brital Nabi 159 En-Nabi 2,328 Temnine Beit Haouch 4,552 Chbay 318 El-Faouqa Chama Snaid Haour Chaaibe 1,223 605 Mousraye 83 Taala 16 9 Khodr 192 Qaa -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Detailed Itinerary

Detailed Itinerary Trip Name: [10 days] People & Landscapes of Lebanon GENERAL Dates: This small-group trip is offered on the following fixed departure dates: October 29th – November 7th, 2021 February 4th – Sunday 13th, 2022 April 15th – April 24th, 2022 October 28th – November 6th, 2022 Prefer a privatized tour? Contact Yūgen Earthside. This adventure captures all the must-see destinations that Lebanon has to offer, whilst incorporating some short walks along the Lebanon Mountain Trail (LMT) through cedar forests, the Chouf Mountains and the Qadisha Valley; to also experience the sights, sounds and smells of this beautiful country on foot. Main Stops: Beirut – Sidon – Tyre – Jezzine – Beit el Din Palace – Beqaa Valley – Baalbek – Qadisha Valley – Byblos © Yūgen Earthside – All Rights Reserved – 2021 - 1 - About the Tour: We design travel for the modern-day explorer by planning small-group adventures to exceptional destinations. We offer a mixture of trekking holidays and cultural tours, so you will always find an adventure to suit you. We always use local guides and teams, and never have more than 12 clients in a group. Travelling responsibly and supporting local communities, we are small enough to tread lightly, but big enough to make a difference. DAY BY DAY ITINERARY Day 1: Beirut [Lebanon] (arrival day) With group members arriving during the afternoon and evening, today is a 'free' day for you to arrive, be transferred to the start hotel, and to shake off any travel fatigue, before the start of your adventure in earnest, tomorrow. Accommodation: Hotel Day 2: Beirut City Tour After breakfast and a welcome briefing, your adventure begins with a tour of this vibrant city, located on a peninsula at the midpoint of Lebanon’s Mediterranean coast. -

View of Late Antiquity In

ARAM, 23 (2011) 489-508. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.23.0.2959670 WALLS OF THE DECAPOLIS Dr. ROBERT SMITH (Mid-Atlantic Christian University) Walls were important to the citizens of the Decapolis cities.1 While the world- view of Late Antiquity interpreted the rise and fall of cities as ultimately being the result of divine intervention, the human construction of defensive walls was still a major civic concern. Walls, like temples, honored a city’s patron deities and fostered a sense of local identity and well-being. These structures, long a bulwark of independence and status for cities in the Levant,2 were present in the Hellenizing pre-Decapolis cities, permitted in the Decapolis during the Roman period and were promoted during the subsequent Byzantine period as well. Instead of fostering local rebellion against a distant Rome or later Con- stantinople, the construction of Decapolis city walls, like other components of the imperial architectural palette, was a strategic asset that served to cultur- ally unify the region’s ethnically and linguistically diverse population.3 The “spiritual walls” of cultural solidarity, established in Hellenism and continued by Rome, together with the physical walls of the Decapolis cities helped to preserve their identities for centuries. The Roman and Byzantine empires depended upon strong loyal cities like those of the Decapolis to sustain their rule in the Levant. WALLS OF PRE-DECAPOLIS CITIES IN THE PRE-ROMAN ERA Cities that would be counted as part of the Decapolis in the Roman Era were typically established in the Hellenistic era on the remains of ancient settle- ments.