Early Lessons from the Implementation of a Relationship and Marriage Skills Program for Low-Income Married Couples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Gaming Introduction/Schedule ...........................................4 Role Playing Games (Campaign) ........................................25 Board Gaming ......................................................................7 Campaign RPGs Grid ..........................................................48 Collectible Card Games (CCG) .............................................9 Role Playing Games (Non-Campaign) ................................35 LAN Gaming (LAN) .............................................................18 Non-Campaign RPGs Grid ..................................................50 Live Action Role Playing (LARP) .........................................19 Table Top Gaming (GAME) .................................................52 NDMG/War College (NDM) ...............................................55 Video Game Programming (VGT) ......................................57 Miniatures .........................................................................20 Maps ..................................................................................61 LOCATIONS Gaming Registration (And Help!) ..................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd Floor, South Hall Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator ..........................................................................................Westin, 14th Floor, Ansley 7/8 Board Games ................................................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd -

Center, 1515 West 6Th Avenue, Stiliwatr, Oklahoma 74074 ($15.00)

DOCUMENT BESDNE ED 140 030 CB 011 311 AUTHOR Nelson, Frank W. TITLE Distributive Education II. Course o. Study. INSTITUTION Oklahoma State Dept. of Vocational and Technical Education, Stillwater. Curriculum and Instructional Materials Center. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 826p. AVAILABLE FRCM Oklahoma State Department of Vocational-Technical Education, Curriculum and Instractional Materials Center, 1515 West 6th Avenue, Stiliwatr, Oklahoma 74074 ($15.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$1.50 Pius Postage. MC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Distributive Education; Economics; Exhibits; *High School Curriculum; Human Relations; Job_Skills; Learning Activities; Merchandising; Publicize; Salesmanship; Senior High Schools; Skin DeVelopment; State Curriculum Guides; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS Cklahoma ABSTRACT This curriculum guide for teacher-coordinators is designed to provide a course of study in distributiveeducation (Distributive Education II) in Oklahoma. Content is in ninesections with each section consisting of one or more instructionalunits: (1) Orientation (Introduction to Distributive Occupations, DECA), (2) Survival Skills (Job Application and Interview, Handling Money,Cash Register, Shoplifting Prevention, and Communications),(3) Human Relations,(4) Selling (Pre-Approach, Approach, andDetermining Needs; Presentation; Overcoming Objections, Close,Suggestion Selling, and Reassurance) , (5) Display,(6) Advertising (Advertising Media; Advertising Layout), (7) Merchandising,(8) Store Organization, and(9) Economics (Economics of Free Enterprise; Government and -

Save the Date RSP: Rabbi Perlman

SUMMER 2019 | SIVAN / TAMUZ / AV 5779 VOLUME 85 NO.9 INSIDE: An Interview with ◾ Tribute to Leonard Cohen Rabbi Sharyn Perlman ◾ FNL with Naomi Less, 9/6/19 Port Washington resident Rabbi Sharyn Perlman was or- dained as a Rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) last year. As a second-career student, Rabbi Perlman brings REGISTER ONLINE FOR new rabbi enthusiasm, combined with the experience of a life lived to her rabbinate. Rabbi Perlman taught “Torah for the Heart” at TBI this Spring, and was acting Rabbi for RELIGIOUS several Shabbatot when Rabbi Mishkin was away. She will be serving as Rabbi-in-Residence while Rabbi Mishkin is SCHOOL on sabbatical the Summer. See Page 13 By way of introducing Rabbi Perlman to the TBI family, she agreed to be inter- viewed for The Tablet, and hopes that you will join her in the coming months for exciting learning, meaningful prayer, and warm schmoozing. TBI: Let’s start with an easy question: How would you prefer to be addressed by your congregants – Rabbi Perlman or Rabbi Sharyn? Save the Date RSP: Rabbi Perlman. Thanks for asking! temple beth israel TBI: Tell us a little about yourself. Where are you from originally? Rabbi Perlman continued on page 2 Sunday, September 8 12 noon Activities throughout the afternoon provided by Crestwood Day Camp Arts & Crafts Music & Entertainment Games • Playground Food Visit us online at www.tbiport.org Contact us at 516-767-1708 Rabbi Perlman continued from page 4 RSP: I’m a born and bred Long Islander. My family lived in Glen Cove until shortly after my bat mitzvah – at Congregation Tifereth Israel – and then we moved Temple Drive, Port Washington NY 11050-3915 to Great Neck, where my 92-year-old mother still lives. -

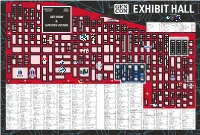

PDF Map of Exhibit Hall

175 275 173 272 273 372 171 270 271 370 371 471 571 ENTERTAINERS’ BOOK 169 268 269 368 468 469 568 SPOTLIGHT SIGNING 167 266 267 366 367 566 666 EXHIBIT CO-SPONSORSHALL 264 265 364 365 464 465 564 664 162 163 363 563 ART SHOW 1163 1363 1462 160 161 260 261 361 460 461 560 561 660 1260 1261 1361 1460 EXHIBITOR 158 & 1159 1258 1359 1458 1459 1559 SERVICES DESK 157 256 456 457 557 1256 1356 1357 1456 1457 1556 1557 1656 SPONSOR LOCATIONS OUTSIDE EXHIBIT HALL Catan Studio .....................................Event Hall Magic: The Gathering.......................Event Hall Square Enix .....................................Event Hall 154 254 255 355 455 1155 1254 1355 1454 1455 1554 1754 1755 1855 1955 2054 Coolstuffinc.com .............................Event Hall Paizo ............................... Sagamore Ballroom Steamforged Games .......................Event Hall EXHIBIT HALL K ENTRANCE AUTHORS’ AVENUE Czech Games Edition ................. ICC 237-239 Pandasaurus Games ........................Event Hall Table of Ultimate Gaming ................Event Hall 353 452 453 552 553 1253 1653 1752 1753 1852 1853 1953 Fantasy Flight Games ......................Event Hall Ravensburger ..................................Event Hall and Tabletop Showroom Forbidden Games ............................Event Hall Renegade Game Studios .................... ICC 139 The Pokémon Company ...................Event Hall 150 151 250 1751 1850 1851 1950 1951 2050 2051 2150 2151 2250 Funko Games ...................................... ICC 141 Rio Grande Games .................... -

UN 0217.Indd

Jornal da Universidade de Fortaleza • Fundação Edson Queiroz • Número 217 – Abril de 2012 • www.unifor.br Estudante e técnica durante a produção da saliva sintética em laboratório da Unifor. Saliva que alivia Há 10 anos, o projeto Saliva Artifi cial atende pessoas carentes que tiveram a diminuição parcial ou total da saliva em decorrência, principalmente, de tratamento radioterápico contra câncer na região da cabeça e pescoço. O projeto propicia aos pacientes, por exemplo, alívio na fala e na deglutição, além de atendimento odontológico. É uma parceria dos cursos de Odontologia e de Farmácia da Unifor com o Hospital Geral de Fortaleza. 02 | CAMPUS & COMUNIDADE editorial sumário CAMPUS & COMUNIDADE Realizações de Humor na televisão Confira o artigo que aborda o humor na televisão através de uma universidade 4 inovações do Núcleo Guel Arraes, da Rede Globo. Saliva sintética surpreendente O projeto Saliva Artificial traz melhorias na vida daqueles que Uma boa iniciativa pode fazer toda a diferença em nossa vida. Ou na vida de ou- 6 tiveram sequelas em decorrência, principalmente, de trata- tros. Ou pode ser boa para todos. E é preciso que uma boa iniciativa seja sempre alvo mentos radioterápicos. de divulgação. Na matéria de capa, trazemos o projeto Saliva Artificial, que atende há dez anos Cobertura vegetal pessoas carentes que tiveram redução parcial ou total da saliva em decorrência, prin- A vasta arborização do campus proporciona um microclima cipalmente, de tratamento radioterápico contra o câncer na região da cabeça e pes- 10 agradável e condições para a criação de animais silvestres coço. A saliva artificial proporciona diversos benefícios aos que são atendidos, como soltos pela Universidade. -

Two-Gether B I R T H T O 1 2 M O N T H S

PARENTING two-gether BIRTH TO 1 2 MONTHS C REV 7/11 PARENTING two-gether BIRTH TO 1 2 MONTHS Contents adapted by the Office of the Attorney General from ”Doin’ the Dad Thing” published by: HEALTHY FAMILIES SAN ANGELO 200 S. Magdalen, San Angelo, Texas 76903 325-658-2771 • www.hfsatx.com i Table of Contents INTRODUCTION: Congratulations! CHAPTER 1 Newborn – the first three months Sleeping – Dressing – Grooming ........................................................................ 3 Diapering .................................................................................................................... 6 Crying ........................................................................................................................... 8 Cry Chart ..................................................................................................................... 10 Feeding ........................................................................................................................ 12 Never Shake A Baby ................................................................................................. 13 Your Child’s Health and Safety ............................................................................ 14 Keeping Your Baby Safe ......................................................................................... 16 Mommy Blues ............................................................................................................ 18 Bonding....................................................................................................................... -

Texas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church 2011 Pre-Conference Journal

Texas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church 2011 Pre-Conference Journal Dear Member of the Texas Annual Conference, Greetings in the name of our Resurrected Savior Jesus Christ. Congratulations on serving as a clergy, lay or alternate member of the Texas Annual Conference. Members of predecessor Methodist conferences that now form the Texas Annual Conference have gathered annually to pray, worship, fellowship and confer about the ministry of the church since 1842. On behalf of the staff and elected leaders, I am delighted to welcome you the 2011 session which will take place May 29-‐June 1, 2011. Conference will be held in e a new venu this — year The George R. Brown Convention Center. We are expecting 2700 approximately people to attend in some capacity. The convention center offers more space and excellent technology. For the first time, voting will be electronic. If you stay in the conference hotel, you will be able to walk to all the sessions, including worship, as well as dine in nearby restaurants. Information is included in this journal to make the -‐ convention center “user friendly” for your stay. I want to encourage e you to mak a special effort to attend one of the District Pre-‐Conference meetings this year. Persons will be present in every district to demonstrate the use of electronic devices voting and review major areas of business. Agenda time is always a at premium during voting years. The district gatherings will give you an opportunity to ask questions and engage in discussion about issues of concern in smaller groups where time is more relaxed. -

CCBC Choices 1989

CCBC Choices 1989 Kathleen T. Horning and Ginny Moore Kruse with Deana Grobe and Merri Lindgren Copyright 0 1990, Friends of the CCBC, Inc. Acknowledgements Thank you to: each of the participants in monthly CCBC Book Discussions during 1989; everyone who participated in ;he annual ~ecemberCCBC Caldecott, Newbery, Batchelder and Coretta Scott King Awards Discussions; all content and other reviewers- especially Janice Beaudin, P. Adika Chabeda, Sandra Gaylord, Barry Hartup, Christine Jenkins, Margaret Jensen, Marguerite Stevenson, Marge Sutinen, William L. Van Deburg and Kris Adams Wendt; the 1989 and 1990 CCBC staffs; Donald Crary and the Friends of the CCBC, Inc., for production and out-of-state distribution. CCBC Choices 1989 was designed by William Kasdorf and produced by Marcy Weiland at Impressions, Inc, Madison, Wisconsin. For information about CCBC publications, Wisconsin residents may send a self- addressed, stamped envelope to: Cooperative Children's Book Center, 4290 Helen C. White Hall, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 600 N. Park Street, Madison, WI 53706. Out-of-state residents: inquire c/o Friends of the CCBC, Inc., P.O. Box 5288, Madison, WI 53705. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. History, People and Places 6 3. The Natural World 9 4. Seasons and Celebrations 11 5. Activities 14 6. Issues in Today's World 15 7. Understanding Oneself and Others 17 8. Arts 19 9. Poetry 20 10. Biography and Autobiography 22 11. Folklore, Mythology and Traditional Literature 23 12. Concept Books 28 13. Books for Toddlers 30 14. Picture Books 32 15. Fiction for New Readers 38 16. Fiction for Young Readers 40 17. -

709Corsicana.Pdf

CORJuly09Covers.qxd 6/20/09 11:39 PM Page 2 July 2009 FromFrom GenerationGeneration toto GenerationGeneration OutOut FromFrom BehindBehind thethe PoeticPoetic PodiumPodium ThoughtsThoughts MexiaMexia OnOn TopTop ofof SpecialSpecial HerHer GameGame SectionSection AtAt HomeHome WithWith KyleKyle andand RockieRockie GlicksmanGlicksman CORJuly09Covers.qxd 6/20/09 11:51 PM Page 3 CORJuly09p1-5.qxd 6/20/09 11:53 PM Page 1 CORJuly09p1-5.qxd 6/20/09 11:53 PM Page 2 CORJuly09p1-5.qxd 6/20/09 11:56 PM Page 3 ContentsJuly 2009, Volume 6, Issue 7 8 14 From Generation Coming Home Again to Generation At Home With Kyle and Rockie Glicksman 24ArtsNOW 34SportsNOW 40BusinessNOW 42EducationNOW Poetic Thoughts On Top of Her Game From the Ground Up Out From Behind the Podium Around TownNOW FinanceNOW On the Cover: 46 54 Old Glory flies proud and free at Bunert Park in Who’s CookingNOW HealthNOW Corsicana. 50 56 Photo by Terri Ozymy. 51 Dining Guide 60 OutdoorsNOW Publisher, Connie Poirier Corsicana Editor, Samantha Daviss Advertising Manager, Linda Moffett Graphic Designers/Production, Julie Carpenter . Allee Brand General Manager, Rick Hensley Contributing Writers, Faith Browning Advertising Representatives, Cherie Chapman . April Gann Managing Editor, Becky Walker Nancy Fenton . Joyce Hagens Linda Roberson . Rick Ausmus Marshall Hinsley . Arlene Honza Creative Director, Jami Navarro Gary Hayden . Joan Kilbourne Linda Dean . Will Epps Brande Morgan . Pamela Parisi Steve Hansen Carolyn Mixon Art Director, Chris McCalla Contributing Editors/Proofreaders, . Jennifer Wylie Billing Manager, Lauren De Los Santos Pat Anthony . Angel Jenkins Morris Steve Randle . Shane Smith Photography, Terri Ozymy Office Manager, Angela Mixon Jaime Ruark . Beverly Shay Eddie Yates . -

Living Working Playing Learning

A KATY MAGAZINE™ PUBLICATION 2014 NEWCOMER & RESOURCE GUIDE Katy sisters Ryanne and Lila Meyer Photo by Stephanie Meyer Photography LIVING WORKING PLAYING LEARNING KatyMagazine.com TRANSFORMING CARE IN OUR COMMUNITY. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PRACTICING MEDICINE AND LEADING IT. Houston Methodist West Hospital offers the services and world-class cardiovascular most technologically advanced, personalized capabilities to our state-of-the-art birthing health care available in the West Houston and center and advanced sports medicine program, Katy communities. From our 24/7 emergency we offer the care you want for your family. 18500 Katy Freeway (@ Barker Cypress) Houston, Texas 77094 houstonmethodist.org/west 832.522.5522 A hop, skip and a jump. " !"! " ! !" ! !"!"" ! "!"!" !"" ""!""" "!"" ""! "!"!" "! !" "! " ! "!"" !"!"" ! !"! "" ! !!"!"!"" !"""!""! " "! "!"! " !"" !!"! "! "!"" !!" " " ""!" ""! ! " ! " !" !" %%"$% !#"$% $!#% ##%!$%"$""%"$% !#"$% $!#%!$%"% #% !#"$% $!#%!%"$% % % % ##% Teacher Jessica Wright with her two children There’s No Place Like Katy, Texas Masahiro, Aki, Runa, and Rio Sugioka Congratulations on finding Katy, Texas! Katy truly is one of the best places in Texas to raise your family. Let me be the first to welcome you with our 2014 edition of Katy Life, the resource and newcomer guide published by Katy Magazine. Katy’s award-winning school system, affordable housing, southern hospitality, and overall quality of life are just a few of the many reasons people move here and call Katy home. Katy is a key part of the fast growing West Houston Energy Corridor, and our population is comprised of thousands of oil families and energy executives. With Houston just a hop, skip, and a jump down Interstate 10 (also known as Katy Fwy.), locals enjoy big city amenities like art, music, theatre, museums, and world-class dining. -

A Catalog of Books from the Collection of Gerrit Lansing Division

The Swarming Possibilities (Some Occult, Unused) in American Life A Catalog of Books From the Collection of Gerrit Lansing Division Leap and Grey Matter Books Covers The Swarming Possibilities (Some Occult, Unused) in American Life Front / inside back: 1. A Catalog of Books From the Collection of Gerrit Lansing De occulta philosophia libri tres. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa [1486-1535]. Inside front / back: 68. Causal Mythology. Charles Olson. 72. Projective Verse. Charles Olson. Division Leap and Grey Matter Books Foreword Adam Davis The Immanent Library Catalog Part I The Occult Part II Teddy Roosevelt Rides the Range Reciting Swinburne Part III Charles Olson and His Circle Part IV Poetry and Literature Bibliography Afterword Sam Burton Thanks Forward. The Immanent Library surprise then that a remarkable poet in the first paragraph - works number of poets on this list were on bibliomancy, stichomancy, gay or queer and began from rhapsodomancy, sortes, and many “All the power of magic is founded upon Eros. forbidden ground. A remarkable other subjects. Reading through The work of Magic works is to bring things number of them were connected Gerrit’s library could make one an together through their inherent similarity.” to the city of Boston, and an even exceedingly well-informed heretic, wider number had a relationship yet the power of it was something – Marsilio Ficino, De Amore. to Lansing and his library. greater. Libraries can have their own genius loci, as powerful a “Nunquam sine phantasmate intelligit anima.” Some of this influence is direct sense of place as New York or and visible. Charles Olson’s influ- Alexandria. -

Mbmbam 490: Ewdaddy Published on December 16Th, 2019 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

MBMBaM 490: Ewdaddy Published on December 16th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family Intro (Bob Ball): The McElroy brothers are not experts, and their advice should never be followed. Travis insists he's a sexpert, but if there's a degree on his wall, I haven't seen it. Also, this show isn't for kids, which I mention only so the babies out there will know how cool they are for listening. What's up, you cool baby? [theme music plays] Justin: Hello, and welcome to My Brother, My Brother, and Me, an advice show for the modern era. I'm your oldest brother, Justin McElroy. Travis: I'm your middlest brother. I've just been handed this… Travis McElroy. Griffin: I'm Griffin. Justin: He‘s Griffin. I'm Justin. And this is… [sings] How we do iiit! Hop bop bop bop bop. This is a holiday special. It‘s our holi—it‘s a holiday special in the sense that it is mid-December. Travis: Yes. Justin: Fair? Travis: Sure. Justin: And the holidays are here again, and we wanted to share with you some of our holiday recommendations. Ways that you can make it really special, specific to um, different— Travis: Can I— Justin: What? Sorry, I was gonna do a sentence, but go ahead. We‘ll pretend there‘s a bracket here in my sentence. And Travis? Travis: Okay. I want to talk about my favorite holiday movies, Justin. Justin: Okay. What are they, Travis? Travis: I like the one— Griffin: I want to talk about my favorite Christmas cookies! Justin: This is a sub-bracket.