Towards a Conception of the Fundamental Values of Catholic Education: What We Can Learn from the Writings of John Paul II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Schools:Report2columns

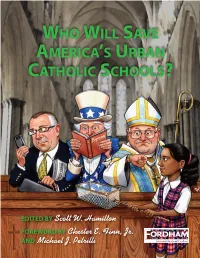

WHO WILL SAVE AMERICA ’S URBAN CATHOLIC SCHOOLS ? EDITED BY Scott W. Hamilton FOREWORD BY Chester E. Finn, Jr. AND Michael J. Petrilli The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts research, issues publications, and directs action projects in elementary/secondary education reform at the national level and in Ohio, with special emphasis on our hometown of Dayton. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Further information can be found at www.edexcellence.net, or by writing to the Institute at 1016 16th St. NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20036. The report is available in full on the Institute's website; additional copies can be ordered at www.edexcellence.net. The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University. WHO WILL SAVE AMERICA’S URBAN CATHOLIC SCHOOLS? EDITED BY Scott W. Hamilton FOREWORD BY Chester E. Finn, Jr. AND Michael J. Petrilli 1 CONTENTS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 FOREWORD 12 INTRODUCTION 21 DIOCESAN/ARCHDIOCESAN LEADERSHIP 22 Wichita: Making Catholic Schools Affordable Again By Bryan O’Keefe 34 Memphis: Revitalization of Diocesan “Jubilee” Schools By Peter Meyer 46 Denver: Marketing Efforts Yield Results By Marshall Allen 55 INDEPENDENT RELIGIOUS ORDER NETWORKS 56 Independent Networks: NativityMiguel & Cristo Rey By Peter Meyer 71 PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR CATHOLIC SCHOOLS 72 Milwaukee: The Mixed Blessing of Vouchers By Marshall Allen 85 Washington, D.C.: Archdiocesan Schools to Go It Alone By John J. Miller 3 97 SUPPORT FROM COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES 98 Higher Education Partners: Catholic Universities Find Ways to Help Urban Schools By Marshall Allen 111 PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT CATHOLIC SCHOOLS 112 American Opinions on Catholic Education By David Cantor, Glover Park Group INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY merica’s urban Catholic schools unfamiliar with the success of inner-city parochial are in crisis. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Recensiones. Starmarket, Teenage Fanclub, Hellsongs Y Santi Campos

RECENSIONES. STARMARKET, TEENAGE FANCLUB, HELLSONGS Y SANTI CAMPOS. © Amador Pérez de Algaba de la Torre. Analista Musical Independiente de Sevilla. España. [email protected] PÉREZ DE ALGABA DE LA TORRE, Amador. (2014). “Recensiones. Starmarket, Teenage Fanclub, Hellsongs y Santi Campos”. Montilla (Córdoba): Revista-fanzine Procedimentum nº 3. Páginas 169-176. 1. Starmarket y su disco “Four Hours Light” (Bcore, 2011). Normalmente las reediciones de discos buscan un interés más comercial que artístico. Intenta hacer beneficios a base de sacar brillo a viejas grabaciones que apelan a la nostalgia del oyente, influenciado por algún acontecimiento que hace que el nombre, del artista en cuestión, vuelva a sonar. Nada más lejos de esto ha sido la intención del sello Bcore, quien acaba de reeditar el fabuloso álbum “Four Hours Light” de la banda sueca Starmarker. Con el arrojo y buen gusto de siempre, el sello barcelonés reedita esta completísima obra que vio la luz por primera vez de la mano de sello norteamericano Deep Elm, en 2000. Disco completo tanto por el contenido como por el formato. Con el soporte de un lp de vinilo blanco de doce pulgadas que incluye bono con código para descarga digital, Bcore nos regala uno de esos grandes discos que nunca pasan de moda y que, gracias a su reedición, hace que muchos amantes de la música popular podamos conocer estas doce canciones llenas de fuerza y ternura a las que se etiqueta como emo. Y es que es emoción lo que produce la escucha de canciones plenas que enganchan desde el primer instante. Herencia del mejor rock and roll que recoge esta banda de Estocolmo en la que todo encaja y cada cual cumple su cometido a la perfección, lo que no es extraño si tenemos en cuenta que los países nórdicos son uno de los mejores escenarios musicales de todos los tiempos, que ya desde la tradición jazz se ganaron un puesto principal en la escena mundial. -

AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 18 SEPTEMBER 14 + SEPTEMBER 21, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date DV- En Vivo Desde Morelia 15 LAT 525832 BANDA MACHOS Años (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 CD- FER 888109 BARLOWGIRL Our Journey…So Far $11.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 524138 CHATHAM, RHYS A Crimson Grail $16.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- ATL 524647 CHROMEO Business Casual $13.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- Business Casual (Deluxe ATL 524649 CHROMEO Edition) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 Business Casual (White ATL A-524647 CHROMEO Colored Vinyl) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525705 CLAPTON, ERIC 2004 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525708 CLAPTON, ERIC 2007 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 COLMAN, Shape Of Jazz To Come (180 ACG A-1317 ORNETTE Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 REP A-524901 DEFTONES White Pony (2LP) $26.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- RRR 177622 DRAGONFORCE Twilight Dementia (Live) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- LAT 525829 EL TRI Sinfonico (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 JACKSON, MILT & HAWKINS, ACG A-1316 COLEMAN Bean Bags (180 Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 287228 KREMER, GIDON -

Teenage Fanclub Grand Prix Mp3, Flac, Wma

Teenage Fanclub Grand Prix mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Grand Prix Country: US Released: 1995 Style: Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1181 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1665 mb WMA version RAR size: 1258 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 379 Other Formats: VOC MP3 MP2 AIFF MIDI WAV ADX Tracklist Hide Credits About You 1 Saxophone [Alto] – Nigel HitchcockSaxophone [Baritone] – Chris WhiteSaxophone [Tenor] – Jamie TalbotTrumpet – Steve Sidwell 2 Sparky's Dream 3 Mellow Doubt 4 Don't Look Back 5 Verisimilitude 6 Neil Jung Tears 7 Cello – Dinah BeamishTrumpet – Steve SidwellViola – Jocelyn PookViolin – Jules Singleton*, Sonia Slany 8 Discolite 9 Say No 10 Going Places 11 I'll Make It Clear 12 I Gotta Know 13 Hardcore/Ballad Credits Co-producer – David Bianco Notes Promo release with back insert only Produced by David Bianco and Teenage Fanclub. Engineered and mixed by David Bianco. Assistant Engineers- Julie Gardner & Jamie Seyberth. Occasional guitar, piano & vocals by David Bianco. Sleeve design by Teenage Fanclub. Track 7 arrangment by Sonia Slany 'About You', 'Verisimilitude', 'Say No' & 'I Gotta Know' written by Raymond McGinley. 'Sparky's Dream', 'Don't Look Back', 'Discolite' & 'Going Places' written by Gerard Love. 'Mellow Doubt', 'Neil Jung', 'Tears', 'I'll Make It Clear' & 'Hardcore/Ballad' written by Norman Blake. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Teenage Grand Prix (LP, Creation CRELP 173L CRELP 173L UK 1995 Fanclub Album + 7", Ltd) Records Grand Prix (LP, Teenage 19075837051 -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Alumni Connection Winter

Alumni FALL 2005 Connection ST. VINCENT-ST. MARY HIGH SCHOOL A BLESSED BEGINNING STVM COMMUNITY GATHERS TO CELEBRATE THE DEDICATION OF JOHN CISTONE FIELD CLASS REUNIONS ALUMNI ALLEY SCHOOL EVENTS FALL SPORTS REVIEW 6 IT’S HAPPENING HERE IN THIS ISSUE STV CLASS OF ’50 REUNITES: DAVE AND ROSE MCMULLEN 4 MASS AND FIELD BLESSING A host of the STVM com- munity gathered September 10, 2005 to dedicate John Cistone Field. 10 FR. SAM CICCOLINI CELEBRATES 35 YEARS 23 OF TOUGH LOVE Thirty-five years ago, Fr. Sam Ciccolini M60 founded Interval Brotherhood Home, a drug and alcohol treatment facility. 21 THANK YOU WERE MAGIC WORDS Shamrock Society Reception was an opportunity to thank those who support our school in so many different ways. 25 IRISH IN THE NEWS Read about how our students and faculty are making a difference each and every day. SHOWCASE ANNA ROSE SHAFFER, KASEY SHAMMO, AND MARY KATE SHAFFER DANCE AT SHOWCASE. FIRST WORD 1 IT’S THAT TIME OF YEAR 27 It’s time to renew your Alumni Association membership. It’s time 2005 HOMECOMING COURT to become a dues paying member of the Alumni Association. Our fiscal year runs from July 1st to June 30th. Your dues help defray costs of alumni events, many of which are gratis like the Alumni 28 Winter Night and the Alumni Memorial Mass; dues help fund the Alumni Association Scholarship; dues pay for Alumni Association sponsored events for the school like the Welcome Freshman Night and the Farewell Senior Mass; dues paying members who have provided their e-mail address receive the E-Connection cyber- FALL SPORTS ROUND-UP COACH WAKEFIELD IGNITES THE newsletter. -

Teenage Fanclub the King Cd

Teenage fanclub the king cd click here to download Super-Rare UK CD (CRECD ). When Teenage Fanclub signed w/ Geffen, they still owed an album to Creation. This collection of covers & strangeness. View credits, reviews, track listings and more about the UK CD release of The King by Teenage Fanclub. Find a Teenage Fanclub - The King first pressing or reissue. Complete your Teenage Fanclub collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. reviews, credits, songs, and more about Teenage Fanclub - The King at Discogs. Complete your Teenage Fanclub collection. The King album cover. Buy The King (CD) by Teenage Fanclub (CD). Amoeba Music. Ships Free in the U.S. Find great deals on eBay for Teenage FANCLUB in Music CDs. Shop with Vinyl LP - Teenage Fanclub / The King Used Creation Indie. $ 5 bids. TEENAGE FANCLUB The King (Scarce UK limited edition 9-track vinyl LP which was made available for sale in the shops for one week only, housed in a. May 3, Each album has been remastered from the original tapes at Abbey Road Studios, London under the A. Heavy Metal 6 - From The King album. 08, Teenage Fanclub, The Ballad Of Bow Evil (Slow And Fast), Rate A ' contractual obligation' budget priced mini album deleted upon the day of it's release. The King, an Album by Teenage Fanclub. Released in August on Creation ( catalog no. CRECD ; CD). Genres: Power Pop, Alternative Rock. Featured. Sep 1, Teenage Fanclub is either the “best band in the world” or the A lot of fans think the album was named Thirteen as a tribute to Big Star. -

Audio + Video 8/17/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 16 AUgUST 17 + AUgUST 24, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 8/17/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- The Switch: Music From The WNR 525420 VARIOUS ARTISTS Motion Picture $13.98 8/17/10 7/28/10 8/17/10 Late Additions Street Date Order Due Date REPLACEMENTS, Don't Tell A Soul (180 Gram ORW A-525652 THE Vinyl) $22.98 8/17/10 7/28/10 CD- TAKING BACK WB 523501 SUNDAY Live From Orensanz $13.99 8/17/10 7/28/10 TEENAGE Bandwagonesque (180 Gram ORW A-525650 FANCLUB Vinyl) $20.98 8/17/10 7/28/10 Last Update: 07/12/10 ARTIST: The Replacements TITLE: Don't Tell A Soul (180 Gram Vinyl) Label: ORW/Original Recordings Group Config & Selection #: A 525652 Street Date: 08/17/10 Order Due Date: 07/28/10 Full Length UPC: 093624962564 Vinyl Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $22.98 Alphabetize Under: R For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock Packaging Specs: Mastered from the original analog tapes by Kevin Grey at Acoustech Mastering Pressed at RTI Description: Originally released in 1989, the band's second major label record, young fans were expecting a record of radio hits and radio was expecting more punk rock antics.. -

St. Andrews Ball Is at Maketewah! Opening a PDF 2 *Schedule of Events 2 Veryone Aspires to Have at Least Black William 3 a Little Fun and Play in Their Life

Make Your Plans for the Fall Meeting, Oct 14th! Mark Your Calendar for St. Andrews!!! ISSUE 13 / FALL ’11 Bill Parsons, Editor 6504 Shadewater Drive Hilliard, OH 43026 513-476-1112 [email protected] THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CALEDONIAN SOCIETY OF CINCINNATI In This Issue: St. X is at Maketewha 1 St. Andrews Ball Is At Maketewah! Opening a PDF 2 *Schedule of Events 2 veryone aspires to have at least Black WIlliam 3 a little fun and play in their life. CSHD 3 EAt Maketewah, it’s members Cinti Highld Dancers 3 and guests have a place that lets them do just that — play through life. Stirling Reopens 4 Maketewah is one of the premiere *Resource List 4 private country clubs in the Midwest. Out of the Sporran 5 Founded in 1910, it’s stately and Scotch on the Rockz 6-19 elegant clubhouse was completed *Email PDF Issue only 7-19* in 1930 and serves as the social center for Maketewah’s outgoing and Band/Marching Units 14* supportive membership. Maketewah takes pride in exceeding guests’ expectations not only in golf, but also in providing a unique dining experience. Guests PAY YOUR DUES! can enjoy a variety of dining options Don’t forget to pay your current at the club, from fine dining to dues. While you’re at it convert to luncheons and more casual dinners. the cyber Gazette, let Robert know. You will find the same impeccable The Caledonian Society of Cincinnati, service and fresh, delicious cuisine Robert Reid, Corspd. Secretary throughout the club. 6052 Delicious Asha Ct The Executive Chef, Rachel and flourish to an evening bedecked Maketewah is one of Loveland OH 45140 Hostiuck, plans a variety of seasonal in Scottish pagentry. -

Scott's Favorite Albums, 1965-1999

Scott's Favorite Albums: 1965-1999 1965 1 HELP! - The Beatles 2 RUBBER SOUL - The Beatles 3 OUT OF OUR HEADS - The Rolling Stones 4 GOING TO A GO-GO - Smokey Robinson and the Miracles 5 HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED - Bob Dylan 6 THE WHO SING MY GENERATION - The Who 7 MR. TAMBOURINE MAN - The Byrds 8 THE SOUNDS OF SILENCE - Simon and Garfunkel 9 KINKS SIZE - The Kinks 10 THE TEMPTATIONS SING SMOKEY - The Temptations 11 TURN TURN TURN - The Byrds 12 BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME - Bob Dylan 13 THEM - Them 14 SUMMER DAYS (AND SUMMER NIGHTS) - The Beach Boys 15 OTIS BLUE - Otis Redding 16 DECEMBER'S CHILDREN (AND EVERYBODY'S) - The Rolling Stones 17 POPPA'S GOT A BRAND NEW BAG - James Brown 18 OVER UNDER SIDEWAYS DOWN - The Yardbirds 19 FOUR TOPS' SECOND ALBUM - The Four Tops 20 I AIN'T A-MARCHIN' NO MORE - Phil Ochs 1966 1 REVOLVER - The Beatles 2 PET SOUNDS - The Beach Boys 3 BLONDE ON BLONDE - Bob Dylan 4 MORE OF THE MONKEES - The Monkees 5 AFTERMATH - The Rolling Stones 6 WALK AWAY RENEE/PRETTY BALLERINA - The Left Banke 7 5D - The Byrds 8 IF YOU CAN BELIEVE YOUR EYES AND EARS - The Mamas and the Papas 9 SHAPES OF THINGS - The Yardbirds 10 HAPPY JACK - The Who 11 PARSLEY, SAGE, ROSEMARY AND THYME - Simon and Garfunkel 12 SOPHISTICATED BEGGAR - Roy Harper 13 BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD - Buffalo Springfield 14 THE EXCITING WILSON PICKETT - Wilson Pickett 15 I GOT YOU (I FEEL GOOD) - James Brown 16 SUNSHINE SUPERMAN - Donovan 17 I FOUGHT THE LAW - The Bobby Fuller Four 18 JEFFERSON AIRPLANE TAKES OFF - Jefferson Airplane 19 THE MONKEES - The Monkees 20 HUMS OF THE LOVIN' SPOONFUL - The Lovin' Spoonful 1967 1 SERGEANT PEPPER'S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND - The Beatles 2 ARE YOU EXPERIENCED? - Jimi Hendrix Experience 3 THE VELVET UNDERGROUND AND NICO - The Velvet Underground 4 THE DOORS - The Doors 5 THE PIPER AT THE GATES OF DAWN - Pink Floyd 6 NEVER LOVED A MAN THE WAY THAT I LOVE YOU - Aretha Franklin 7 PISCES, AQUARIUS, CAPRICORN & JONES LTD. -

Vision for Duke' Program Reinstated for Fall by JOSEPH HALL for Student Affairs

Nice beard! Steve Martin stars with an all-star cast in 'Grand Canyon,' which explores life's highs THE CHRONICLE and lows. For a review, see R&R. THURSDAY, JANUARY 23, 1992 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 87, NO. 77 'Vision for Duke' program reinstated for fall By JOSEPH HALL for student affairs. Dickerson said ties to the controversial new Di ure of communication between The Vision for Duke program, she thought the program was im versity Awareness Program. different departments in the Uni which was placed on temporary portant for helping to facilitate "There have been some misun versity. hold in December, has been rein relations between members of a derstandings. Duke's Vision has Both programs use small group stated for next year's freshmen diverse student body. "We want no connection with the informa discussions to promote awareness orientation. to continue discussions about tion being gathered [about the of different cultures. The discus The Vision for Duke program, what it means to have a largely Diversity Awareness Program]," sions are similar in content but formerly known as Duke's Vision, heterogenous community at said Roy Weintraub, professor of different in format. The Diversity is a series of discussions and lec Duke," Dickerson said. economics. Weintraub is also Awareness Program would be an tures that all incoming freshmen The Vision for Duke program chairman ofthe Academic Coun ongoing attempt by the adminis attend during orientation week. was put on hold by President cil, which is investigating the tration to provide all University "The Duke Vision can continue professors, employees and stu Keith Brodie apparently as a mis programs.