Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 4.1. the Political Subdivisions of the Antilles, Size of the Islands, and Representative Climatic Data

Table 4.1. The political subdivisions of the Antilles, size of the islands, and representative climatic data. sl= sea level. Compiled from various sources. Area (km2) Climatic data Site/elev. (m) MAT(oC) MAP (mm/yr) Greater Antilles (total area 207,435 km2) Cuba 110,860 Nueva Gerona 65 25.3 1793 Pinar del Rio 26 1610 Havana 26 25.1 1211 Cienguegos 32 24.6 98.3 Camajuani 110 22.8 1402 Camagữey 114 25.2 1424 Santiago de Cuba 38 26.1 1089 Hispaniola 76,480 Haiti 27,750 Bayeux 12 24.7 2075 Les Cayes 7 25.7 2042 Ganthier 76 26.2 792 Port-au-Prince 41 26.6 1313 Dominican Republic 48,730 Pico Duarte 2960 - (est. 12) 1663 Puerto Plata 13 25.5 1663 Sanchez 16 25.2 1963 Ciudad Trujillo 19 25.5 1417 Jamaica 10,991 S. Negril Point 10 25.7 1397 Kingston 8 26.1 830 Morant Point sl 26.5 1590 Hill Gardens 1640 16.7 2367 Puerto Rico 9104 Comeiro Falls 160 24.7 2011 Humacao 32 22.3 2125 Mayagữez 6 25 2054 Ponce 26 25.8 909 San Juan 32 25.6 1595 Cayman Islands 264 Lesser Antilles (total area 13,012 km 2) Antigua and Barbuda 81 Antigua and Barbada 441 Aruba 193 Barbados 440 Bridgetown sl 27 1278 Bonaire 288 British Virgin Islands 133 Curaçao 444 Dominica 790 26.1 1979 Grenada 345 24.0 4165 Guadeloupe 1702 21.3 2630 Martinique 1095 23.2 5273 Montesarrat 84 Saba 13 Saint Barthelemy 21 Saint Kitts and Nevis 306 Saint Lucia 613 Saint Marin 3453 Saint Vicent and the Grenadines 389 Sint Eustaius 21 Sint Maarten 34 Trinidad and Tobago 5131 + 300 Trinidad Port-of-Spain 28 26.6 1384 Piarco 11 26 185 Tobago Crown Point 3 26.6 1463 U.S. -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Indigenous Gold from St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands: a Materials-Based Analysis

1 ABSTRACT INDIGENOUS GOLD FROM ST. JOHN, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS: A MATERIALS-BASED ANALYSIS Stephen E. Jankiewicz, MA Department of Anthropology Northern Illinois University, 2016 Dr. Mark W. Mehrer, Director The purpose of this research is to examine the origin, manufacturing technique, function, and meaning of metals used during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries on the island of St. John, United States Virgin Islands. This project focuses on two metal artifacts recovered during National Park Service excavations conducted between 1998 and 2001 at a shoreline indigenous site located on Cinnamon Bay. These objects currently represent two of only three metal artifacts reported from the entire ancient Lesser Antilles. Chemical and physical analyses of the objects were completed with nondestructive techniques including binocular stereomicroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, and particle-induced X-ray emission spectrometry with assistance from laboratories located at Northern Illinois University, Beloit College, Hope College and The Field Museum. This data will be combined with contextual site data and compared to other metal objects recovered throughout the ancient Caribbean. i NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2016 INDIGENOUS GOLD FROM ST. JOHN, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS: A MATERIALS-BASED ANALYSIS BY STEPHEN E. JANKIEWICZ ©2016 Stephen E. Jankiewicz A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Thesis Advisor: Dr. Mark W. Mehrer ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not exist without the help and support of so many wonderful people. I am forever indebted to all of you. I would like to first thank my advisor Dr. -

First Records of the Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus Lugubris

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7 Article in press Open Access © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Rapid Communication CORRECTED PROOF First records of the mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris Duméril and Bibron, 1836), common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus in Duméril, 1836), and Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko Linnaeus, 1758) on Curaçao, Dutch Antilles, and remarks on their Caribbean distributions Jocelyn E. Behm1,2,*, Gerard van Buurt3, Brianna M. DiMarco1,4, Jacintha Ellers2, Christian G. Irian1, Kelley E. Langhans1, Kathleen McGrath1, Tyler J. Tran1 and Matthew R. Helmus1 1Integrative Ecology Lab, Center for Biodiversity, Department of Biology, Temple University, 1925 N. 12th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122 USA 2Department of Ecological Science – Animal Ecology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081HV Amsterdam, Netherlands 3Kaya Oy Sprock 18, Curaçao 4Department of Biology, Drexel University, 3245 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103 USA Author e-mails: [email protected] (JEB), [email protected] (GB), [email protected] (BMD), [email protected] (JE), [email protected] (CGI), [email protected] (KEL), [email protected] (KM), [email protected] (TJT), [email protected] (MRH) *Corresponding author Received: 27 June 2018 / Accepted: 3 September 2018 / Published online: 16 October 2018 Handling editor: Stelios Katsanevakis Abstract Globally, geckos (Gekkonidae) are one of the most successful reptile families for exotic species. With the exception of the widespread invader, Hemidactylus mabouia, however, introductions of exotic gecko species are a more recent occurrence in the Caribbean islands despite extensive introductions of exotic geckos in the surrounding Caribbean region. Here we report three new exotic gecko species establishments on the mid-sized Caribbean island of Curaçao (Leeward Antilles). -

Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) and Barbados 2010-2015

OFFICE OF EVALUATION Country programme evaluation series Evaluation of FAO’s contribution to Members of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) and Barbados 2010-2015 March 2016 COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION SERIES Evaluation of FAO’s contribution to Members of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) and Barbados, 2010-2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS OFFICE OF EVALUATION March 2016 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Office of Evaluation (OED) This report is available in electronic format at: http://www.fao.org/evaluation The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or devåelopment status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

WT/TPR/S/299/Rev.1 22 September 2014

WT/TPR/S/299/Rev.1 22 September 2014 (14-5261) Page: 1/374 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT OECS-WTO MEMBERS Revision This report, prepared for the third Trade Policy Review of OECS-WTO Members, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from OECS-WTO Members on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Angelo Silvy (tel: 022 739 5249), Usman Ali Khilji (tel: 022 739 6936), Rosen Marinov (tel: 022 739 6391), and Nelnan Koumtingue (tel: 022 739 6252). Document WT/TPR/G/299/Rev.1 contains the policy statement submitted by OECS-WTO Members. Note: This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/299/Rev.1 • OECS-WTO Members - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 5 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Real Economy .......................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Monetary and Exchange Policy .................................................................................... 12 1.2.1 Fiscal policy ......................................................................................................... -

Leeward Islands Yacht Charter Guide

CARIBBEAN LEEWARD ISLANDS YACHT CHARTER GUIDE Don't miss: • The Pump House - an old salt pump house, now a restaurant and bar. • Walkblake House - the oldest house on the island and open to visitors. • Sandy Island - great reefs with good snorkeling and beach combing. Neville Connors Sandy Island restaurant may be open for lunch. • Prickly Pear Cays - great white beaches excellent for snorkeling, whistling rocks and tidal pools. • Seal Island Reef - one of the seven marine parks. • Scilly Cay - private island within Anguilla that serves huge lobster and amazing rum punches! DAY 1 - ST MAARTEN On the island of St. Maarten, you can do what comes naturally, live in the moment, explore without limits, and renew your passion for life. Divided into two, the northern side of St Maarten is French and the southern part is Dutch. From the breathtaking cliffs of Cupecoy to a beach where planes come so close you can practically touch them; and all the restaurants, casinos, nightclubs and beaches in between. From the ordinary to the extraordinary, the possibilities are limitless. Once on board, you will make your way through the bridge out of Simpson Bay and start your journey to Anguilla, just a short cruise away. DAY 2 - ANGUILLA DAY 3 - ST BARTS LEEWARD ISLANDSLEEWARD Colorful Anguilla, part of the British West Indies, is an Difficult for the typical commercial traveller to reach, St upscale splash in the Eastern Caribbean. Showing both its Barts has retained its French traditions with exquisite cuisine, British and African influences, Anguilla puts on a plethora excellent boutique shopping and exclusive beaches. -

Citizenship, Descent and Place in the British Virgin Islands

Bill Maurer Sta1iford University Children of Mixed Marriages on Virgin Soil: Citizenship, Descent and Place in the British Virgin Islands In this essay, I describe a three-stranded argument over who has rightful claim to citizenship in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). Specifically, this essay demonstrates how the law conjures up a domain of "nature" that infonns positions in this argument. There are three parties to this debate: citizens of the BVI who never went abroad for education and employment, citizens of the BVI who left the territory in the 1960s and are now returning, and immigrants to the BVI and their children. For citizens who never emigrated, the law helps construct the nature of identity in tenns of descent, blood, and "race." For immigrants and their children, who make up fifty percent of the present population, the law lends emphasis to region and jurisdiction to construct identity in tenns of predetennined places. For return emigre British Virgin Islanders, the law enables notions of individual ability that appear to make place- and race-based identities superfluous. I will demonstrate how conceptions of belonging and identity based on place and conceptions based on descent work in concert with notions of individual ability to naturalize inequalities between British Virgin Islanders and immigrants. Specifically, I will focus on the inequalities between those who emigrated and those who stayed behind, and between those who emigrated and those BVIslander and immigrants who now work for them. I argue that the law, especially citizenship but also the laws of jurisdictional division, is critical to the creation and maintenance of these competing identities and the inequalities they cover over or remove from discussion. -

A Study of the Eighteenth-Century Irish Community at Saint Croix, Danish West Indies

Irish Migration Studies in Latin America Beyond Kinship: A Study of the Eighteenth-century Irish Community at Saint Croix, Danish West Indies By Orla Power Abstract The Irish trading post, and its associated sugar plantations on the Danish island of Saint Croix during the eighteenth century, is fascinating in that it reflects a cultural liaison unusual in the study of the early modern Irish diaspora. Although the absence of a common religion, language or culture was indicative of the changing nature of Caribbean society, the lack of a substantial ‘shared history’ between Ireland and Denmark encourages us to look beyond conventional notions of the organisation of Irish-Caribbean trade. The traditional model of the socially exclusive Irish mercantile network, reaching from Ireland, England, France and Spain to the Caribbean colonies and back to the British metropole, although applicable, does not entirely explain the phenomenon at Saint Croix. Instead, the migration of individuals of mixed social backgrounds from the British Leeward Islands to Saint Croix reflects the changing nature of the kinship network in response to the diversification of the Caribbean marketplace. Saint Croix. Finally, the concept of the Introduction ‘metropole’ is examined within the context of At the height of the Seven Years’ War (1756- the sugar trade. The islanders did not always 1763) between the European colonial powers, consider London, which acted as a focal point the Irish community at Saint Croix in the for Irish kinship networks, as the hub of their Danish West Indies was responsible for some Atlantic world. 30 per cent of official Danish sugar exports from the island [1]. -

Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, . Leeward Islands, Windward Islands, Barbados, and British Guiana

FILE COPY ONLY Do Not Remove FDCD • = ERS JAMAICA, TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO, . LEEWARD ISLANDS, WINDWARD ISLANDS, BARBADOS, AND BRITISH GUIANA Projected Levels of Demand, Supply, and Imports of Agricultural Products to 197 5 FOREIGN REGIONAL ANALYSIS DIVISION ECONOMIC RESEARCH SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 90 so 40 CARIBBEAN AREA 0 200 400 MILES U N T E D I I I I 0 200. 400 KILOMETERS 35 S T A T E s ' Blll'mucla 30 T I c GULF OF A T L A N MEXICO 25 N 0 c E A )' Caicos p~. c:J ..; ,, Turks G R e 20 ,.,. ~0 ~~ 1- % Caymanislands ~ PUERTO ft.. ~"#" ,f -.-~ .p RICO -4~- ,_,. ,... /II "7. c c:::/ ~ ··so ~ 'll cl' ~ '>'" • Barbuda .., - ,. ....i>o. ....• il' JAMA~aston ._ tu-'a''..,..,\s~ ., Antigua • ./ ., s,t. ~ ., ... ou .....,.,,.. cJl: Guadeloupe 'i) Dominica 1.5 N s E A ~~Martinique~ lfi ...... .... • Q .., , St.Luc•ao "' " .;- St. Vincent 0 Ba~dos ~ ,_ GRENADINE .: ~ ISLANDS o" Grenada i t.•• .r· ( 10 j ~\. r VENEZUELA ( '··-.. - .. , r· ... \.-··-··"") (_ BRITISH ( '\-·· GUIANA •• PACIFIC .' .... ~-·. ....... .r·-'··_/ '"'I'.. ~r.. SURINAM COLOMBIA "' J : .,, . I l .. ~ \ \.~c-··{_,. ...;· .........<\ ,, r.. ' .. r·· .. ,.--··- "·\ _,... .. ....;v ,_\ ~~, ___ ...... OCEAN ··......... r. ...... 0 \.. .. _, .., .. 0 8 R A z L \'\ '-. ECUADOR ! .. " ~ 85 •/ 75 1"1 65 60 55 .. _.~._,...., 70! U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NEG. ERS 2971-64(6) ECONOMIC RESEARCH SERVICE This report was published in Israel with Public Law 480 (104a) local currency funds made available through the Foreign Agricultural Service, U.s. Department of Agriculture Published for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations Printed in Jerusalem by S. -

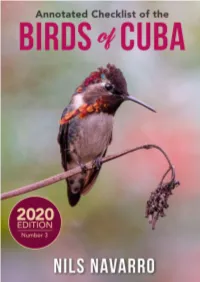

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Final Report

Darwin Plus: Overseas Territories Environment and Climate Fund - Final Report Important note - to be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be a maximum of 20 pages in length, excluding annexes Darwin Project Information Project Ref Number DPLUS016 Project Title Caicos pine forests: mitigation for climate change and invasive species Territory(ies) Turks and Caicos Islands Contract Holder Institution Royal Botanic Gardens Kew Partner Institutions Department of Environment and Maritime Affairs (DEMA) Grant Value £199,693 Start/end date of project April 2014 to March 2016 Project Leader Martin Hamilton Project website http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/research-data/science- directory/projects/turks-and-caicos-islands-pine-recovery Report author and date Martin Hamilton and Michele Sanchez, 24 May 2016 PLEASE NOTE: Supporting documents referred to in this report as Annexes have been uploaded to an FTP site as a single zip file that can be downloaded from here. Individual links are also provided in the Annex sections at the end of this document. 1 Project Overview The Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) are home to the Caicos pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis) and one of the UK Overseas Territories located in the Caribbean region in the south eastern end of the Lucayan archipelago (TCI and The Bahamas) (Figure 1). The Caicos pine is the National Tree of TCI and also a foundation species of the Pine Rockland ecosystems which only occur on four islands in the northern Bahamas and three islands (Pine Cay, North Caicos and Middle Caicos) in TCI (Figure 2).