Reading Augustine's De Trinitate Through Jean-Luc Marion a DI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHIL 269: Philosophy of Sex and Love: Course Outline

PHIL 269: Philosophy of Sex and Love: Course Outline 1. Title of Course: Philosophy of Sex and Love 2. Catalogue Description: The course investigates philosophical questions regarding the nature of sex and love, including questions such as: what is sex? What is sexuality? What is love? What kinds of love are possible? What is the proper morality of sexual behavior? Does gender, race, or class influence how we approach these questions? The course will consider these questions from an historical perspective, including philosophical, theological and psychological approaches, and then follow the history of ideas from ancient times into contemporary debates. A focus on the diversity theories and perspectives will be emphasized. Topics to be covered may include marriage, reproduction, casual sex, prostitution, pornography, and homosexuality. 3. Prerequisites: PHIL 110 4. Course Objectives: The primary course objectives are: To enable students to use philosophical methods to understand sex and love To enable students to follow the history of ideas regarding sex and love To enable students to understand contemporary debates surrounding sex and love in their diversity To enable students to see the connections between the history of ideas and their contemporary meanings To enable students to use (abstract, philosophical) theories to analyze contemporary debates 5. Student Learning Outcomes The student will be able to: Define the direct and indirect influence of historical thinkers on contemporary issues Define and critically discuss major philosophical issues regarding sex and love and their connections to metaphysics, ethics and epistemology Analyze, explain, and criticize key passages from historical texts regarding the philosophy of sex and love. -

The Advocate - July 23, 1959 Catholic Church

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall The aC tholic Advocate Archives and Special Collections 7-23-1959 The Advocate - July 23, 1959 Catholic Church Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Catholic Church, "The Advocate - July 23, 1959" (1959). The Catholic Advocate. 98. https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate/98 Sodality Congress Bishop Sheen to Petitions Ask Speak at Stadium The Advocate Official Publication of the Archdiocese of Newark, N. J. and Diocese of Paterson, N. J. For VOL. NO. 30 Vote 8, on Demonstration THURSDAY, JULY 23, 1959 PRICE TEN CENTS NEWARK Auxiliary Bishop Fulton J. Sheen of Now York has accepted an invitation to address an inter- national Marian rally in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe at Jersey City's Roosevelt Stadium, Sunday, Aug. 23. Law Bishop Sheen, national director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, is in- Sunday ternationally known as a speak- Catholics “a deep sense of re He er had appeared for years for the of By Edward J. Grant than sponsibility conduct | $lOO or more than $2OO for Quota evf IOS. of the voter* in on the radio and television pro world affairs" NEWARK in discretion of each and for applying Church and busi- third offense or. municipality was set. grams of Catholic and the Hour, Christian principles in nras moved the for A drive Social, groups speedily ahead court, imprisonment not strong will be made to in has later years conducted his civic and this toward cultural affairs. -

Michael Jackson the Man and the Message

Michael Jackson The Man and the Message Getting to know his greatest concerns through his own words “I really do wish people could understand me some day.” Michael Jackson The following text consists of quotes that are taken from radio and TV interviews, speeches and public statements, poems and reflections, song lyrics, handwritten notes and letters. The earliest quote is from 1972, the latest from 2009. Since the media rather concentrated on questions in terms of gossip and scandal, this compilation should provide an opportunity to get a more complete impression of Michael Jackson's message and his most important concerns... L O V E There are two kinds of music. One comes from the strings of a guitar, the other from the strings of the heart. One sound comes from a chamber orchestra, the other from the beating of the heart's chamber. One comes from an instrument of graphite and wood, the other from an organ of flesh and blood. This loftier music [...] is more pleasing than the notes of the most gifted composers, more moving than a marching band, more harmonious than a thousand voices joined in hymn and more powerful than all the world's percussion instruments combined. That is the sweet sound of love. Human knowledge consists not only of libraries of parchment and ink – it is also comprised of the volumes of knowledge that are written on the human heart, chiseled on the human soul, and engraved on the human psyche. Food is something we all need physically, but so is love, the deeper nourishment, that turns us into who we are. -

From August, 1861, to November, 1862, with The

P. R. L. P^IKCE, L I E E A E T. -42 4 5i f ' ' - : Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/followingflagfro6015coff " The Maine boys did not fire, but had a merry chuckle among themselves. Page 97. FOLLOWING THE FLAG. From August, 1861, to November, 1862, WITH THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC. By "CARLETON," AUTHOR OF "MY DAYS AND NIGHTS ON THE BATTLE-FIELD.' BOSTON: TICKNOR AND FIELDS. 1865. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864, by CHARLES CARLETON COFFIN, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. University Press: Welch, Bigelow, and Company, Cambridge. PREFACE. TT will be many years before a complete history -*- of the operations of the armies of the Union can be written ; but that is not a sufficient reason why historical pictures may not now be painted from such materials as have come to hand. This volume, therefore, is a sketch of the operations of the Army of the Potomac from August, 1861, to November, 1862, while commanded by Gener- al McOlellan. To avoid detail, the organization of the army is given in an Appendix. It has not been possible, in a book of this size, to give the movements of regiments ; but the narrative has been limited to the operations of brigades and di- visions. It will be comparatively easy, however, for the reader to ascertain the general position of any regiment in the different battles, by con- sulting the Appendix in connection with the narrative. -

Cartel, Code, and Consequences At

May 7, 2015 Eric Leonard General Orders No. 5-15 May 2015 CARTEL, CODE, AND CONSEQUENCES AT ANDERSONVILLE IN THIS ISSUE MCWRT News …………………………..… page 2 I have read in my earlier years about prisoners in the revolutionary war, and other wars. It sounded Announcements ……..………………….. page 3 noble and heroic to be a prisoner of war, and accounts of their adventures were quite romantic; but Coming Events ……………………………. page 4 the romance has been knocked out of the prisoner of war business, higher than a kite. It’s a fraud. Sesquicentennial News ………….. pages 5-6 John L. Ransom - Brigade Quartermaster From the Field ……………..……..... pages 7-8 9th Michigan Cavalry and prisoner at Andersonville 2015 Great Lakes Forum …………….. page 8 At Andersonville prison alone, nearly 13,000 men died over 14 months – an Wanderings ………………………………... page 9 average of more than 30 a day. Overall, 30,000 Union and 26,000 Confederate Meeting Reservation Form …….… page 10 soldiers died in captivity. Deaths at Andersonville represented 29% of the prison population. The death rate at the North’s prison in Elmira had a 24% death rate Between the Covers .……….… pages 10-11 with 3,000 dead, many due to illness. In Memoriam ……………………………. page 11 Quartermaster’s Regalia …………… page 12 Historians continue to debate whether the conditions in Civil War prisons were the result of insufficient resources and mismanagement or something more May Meeting at a Glance insidious – retaliation and deliberate cruelty. Our May speaker is clear on this Wisconsin Club issue: “We did this to ourselves.” th 9 and Wisconsin Avenue In his presentation to our Round Table, Eric Leonard will speak to us about [Jackets required for the dining room.] how the challenge of managing military prisoners took both sides by surprise at 5:30 p.m. -

View to the Quiet of His Rural Home

94 American Antiquarian Society. [Oct. A FORGOTTEN PATRIOT. BY HENRY S. N0UU8E. OF self-sacrificing patriots who in troublous times have proved themselves worthy the lasting gratitude of the com- monwealth, very many have found no biographer ; but none seem more completely forgotten, even in the towns of which they were once the ruling spirits, than the officers who led the Massachusetts yeomanry during those tedious campaigns of the French and Indian War, which awoke the British colonies to consciousness of their strength and thereby hastened the founding of the Republic. A few in- cidents in the honorable career of one of these unremem- bered patriots—one whom perhaps diffidence only, pre- vented from being a very conspicuous figure in the battles for independence—I have brought together, and offer as faint, unsatisfying outlines of an eventful and useful life. In "Appleton's Cyclopœdia of American Biography," published in 1889, twenty-two lines are given to General John Whitcomb, nearly every date and statement in which is erroneous. It is alleged therein that he was born "about 1720, and died in 1812"; and the brief narrative is embel- lished with a romantic tale wholly borrowed from the mili- tary experience of a younger brother. Colonel Asa Whitcomb. Biographical notes in volumes XII. and XVIII. of the Essex Institute Historical Collections perpetuate like errors of date. Even in the most voluminous histories of the building of the Eepublic, this general's name is barely, or not at all mentioned. John Whitcomb, or Whetcomb as the family always 1890.] A Forgotten Patriot. -

Philosophy of Love and Sex Carleton University, Winter 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays, 6:05-7:25Pm, Azrieli Theatre 301

PHIL 1700 – Philosophy of Love and Sex Carleton University, winter 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays, 6:05-7:25pm, Azrieli Theatre 301 Professor: Annie Larivée Office hours: 11:40-12:40pm, Mondays and Wednesdays (or by appointment) Office: 3A49 Paterson Hall Email: [email protected] Tel.: (613) 520-2600 ext. 3799 Philosophy of Love and Sex I – COURSE DESCRIPTION Love is often described as a form of madness, a formidable irrational force that overpowers our will and intelligence, a condition that we fall into and that can bring either bliss or destruction. In this course, we will challenge this widely held view by adopting a radically different starting point. Through an exploration of the Western philosophical tradition, we will embrace the bold and optimistic conviction that, far from being beyond intelligibility, love (and sex) can be understood and that something like an ‘art of love’ does exist and can be cultivated. Our examination will lead us to question many aspects of our experience of love by considering its constructed nature, its possible objects, and its effects –a process that will help us to better appreciate the value of love in a rich, intelligent and happy human life. We will pursue our inquiry in a diversity of contexts such as love between friends, romantic love, the family, civic friendship, as well as self-love. Exploring ancient and contemporary texts that often defend radically opposite views on love will also help us to develop precious skills such as intellectual flexibility, critical attention, and analytic rigor. Each class will be devoted to exploring one particular question based on assigned readings. -

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia Non È Altro Che Amistanza a Sapienza » Nadja

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia non è altro che amistanza a sapienza » Abstract: This is the opening speech of the SIEPM world Congress held in Freising in August 2012. It illustrates the general theme of the Congress – The Pleasure of Knowledge – by referring mainly to the Roman (Cicero, Seneca) and the medieval Latin and vernacular tradition (William of Conches, Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Brunetto Latini), with a special emphasis on Dante’s Convivio. Nadja Germann, Logic as the Path to Happiness: Al-Fa-ra-bı- and the Divisions of the Sciences Abstract: Divisions of the sciences have been popular objects of study ever since antiquity. One reason for this esteem might be their potential to reveal in a succinct manner how scholars, schools or entire societies thought about the body of knowledge available at their time and its specific structure. However, what do classifications tell us about thepleasures of knowledge? Occasionally, quite a lot, par- ticularly in a setting where the acquisition of knowledge is considered to be the only path leading to the pleasures of ultimate happiness. This is the case for al-Fa-ra-b-ı (d. 950), who is at the center of this paper. He is particularly interesting for a study such as this because he actually does believe that humanity’s final goal consists in the attainment of happiness through the acquisition of knowledge; and he wrote several treatises, not only on the classification of the sciences as such, but also on the underlying epistemological reasons for this division. Thus he offers excellent insight into a 10th-century theory of what knowledge essentially is and how it may be acquired, a theory which underlies any further discussion on the topic throughout the classical period of Islamic thought. -

An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 36 Issue 3 November 2011

An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 36 Issue 3 November 2011 EDITORIAL: Spiritual Disciplines 377 D. A. Carson Jonathan Edwards: A Missionary? 380 Jonathan Gibson That All May Honour the Son: Holding Out for a 403 Deeper Christocentrism Andrew Moody An Evaluation of the 2011 Edition of the 415 New International Version Rodney J. Decker Pastoral PENSÉES: Friends: The One with Jesus, 457 Martha, and Mary; An Answer to Kierkegaard Melvin Tinker Book Reviews 468 DESCRIPTION Themelios is an international evangelical theological journal that expounds and defends the historic Christian faith. Its primary audience is theological students and pastors, though scholars read it as well. It was formerly a print journal operated by RTSF/UCCF in the UK, and it became a digital journal operated by The Gospel Coalition in 2008. The new editorial team seeks to preserve representation, in both essayists and reviewers, from both sides of the Atlantic. Themelios is published three times a year exclusively online at www.theGospelCoalition.org. It is presented in two formats: PDF (for citing pagination) and HTML (for greater accessibility, usability, and infiltration in search engines). Themelios is copyrighted by The Gospel Coalition. Readers are free to use it and circulate it in digital form without further permission (any print use requires further written permission), but they must acknowledge the source and, of course, not change the content. EDITORS BOOK ReVIEW EDITORS Systematic Theology and Bioethics Hans -

Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: the Meaning of His/Her Own Life

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 12 Zest for Progress Zeal of Partnership Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: The Meaning of His/Her Own Life Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ Name of School: ___________________________ WHAT I NEED TO KNOW? An unexamined life is a life not worth living (Plato). Man alone of all creatures is a moral being. He is endowed with the great gift of freedom of choice in his actions, yet because of this, he is responsible for his own freely chosen acts, his conduct. He distinguishes between right and wrong, good and bad in human behavior. He can control his own passions. He is the master of himself, the sculptor of his own life and destiny. (Montemayor) In the new normal that we are facing right now, we can never stop our determination to learn from life. ―Kung gusto nating matuto maraming paraan, kung ayaw naman, sa anong dahilan?‖ I shall present to you different philosophers who advocated their age in solving ethical problems and issues, besides, even imparted their age on how wonderful and meaningful life can be. Truly, philosophy may not teach us how to earn a living yet, it can show to us that life is worth existing. It is evident that even now their legacy continues to create impact as far as philosophy and ethics is concerned. This topic: Reflect on the meaning of his/her own life, will help you understand the value and meaning of life since it contains activities that may help you reflect the true meaning and value of one’s living in a critical and philosophical way. -

Renewal Journal Vol 4

Renewal Journal Volume 4 (16-20) Vision – Unity - Servant Leadership - Church Life Geoff Waugh (Editor) Renewal Journals Copyright © Geoff Waugh, 2012 Renewal Journal articles may be reproduced if the copyright is acknowledged as Renewal Journal (www.renewaljournal.com). Articles of everlasting value ISBN-13: 978-1466366442 ISBN-10: 1466366443 Free airmail postage worldwide at The Book Depository Renewal Journal Publications www.renewaljournal.com Brisbane, Qld, 4122 Australia Logo: lamp & scroll, basin & towel, in the light of the cross 2 Contents 16 Vision 7 Editorial: Vision for the 21st Century 9 1 Almolonga, the Miracle City, by Mell Winger 13 2 Cali Transformation, by George Otis Jr 25 3 Revival in Bogatá, by Guido Kuwas 29 4 Prison Revival in Argentina, by Ed Silvoso 41 5 Missions at the Margins, Bob Ekblad 45 5 Vision for Church Growth, by Daryl & Cecily Brenton 53 6 Vision for Ministry, by Geoff Waugh 65 Reviews 95 17 Unity 103 Editorial: All one in Christ Jesus 105 1 Snapshots of Glory, by George Otis Jr. 107 2 Lessons from Revivals, by Richard Riss 145 3 Spiritual Warfare, by Cecilia Estillore Oliver 155 4 Unity not Uniformity, by Geoff Waugh 163 Reviews 191 Renewal Journals 18 Servant Leadership 195 Editorial: Servant Leadership 197 1 The Kingdom Within, by Irene Alexander 201 2 Church Models: Integration or Assimilation? by Jeanie Mok 209 3 Women in Ministry, by Sue Fairley 217 4 Women and Religions, by Susan Hyatt 233 5 Disciple-Makers, by Mark Setch 249 6 Ministry Confronts Secularisation, by Sam Hey 281 Reviews 297 19 -

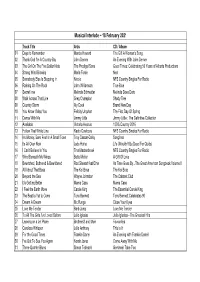

18 02 2021 Playlist

Musical Interlude ~ 18 February 2021 Track Title Artist CD / Album 01 Days to Remember Marcia Howard The Gift A Woman's Song 02 Thank God I'm A Country Boy John Denver An Evening With John Denver 03 The Girl On The Five Dollar Note The Prodigal Sons Good Times: Celebrating 50 Years of Alberts Productions 04 Strong Wind Blowing Maria Forde Next 05 Somebody Else Is Stepping In Nicole NFS Country Singles For Radio 06 Raining On The Rock John Williamson True Blue 07 Secret love Melinda Schneider Melinda Does Doris 08 Walk Across That Line Greg Champion Shady Tree 09 Country Storm Aly Cook Brand New Day 10 You Know I Miss You Felicity Urquhart The First Day Of Spring 11 Dance With Me Jimmy Little Jimmy Little : The Definitive Collection 12 Available Victoria Avenue 100% Country 2016 13 Follow That White Line Radio Cowboys NFS Country Singles For Radio 14 No Money, Bare Feet In A Small Town Troy Cassar-Daley Songlines 15 Its All Over Now Jade Hurley Life (Wouldn't Be Dead For Quids) 16 I Can't Believe In You Tina Mastenbroek NFS Country Singles For Radio 17 Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler A Gift Of Love 18 Bewitched, Bothered & Bewildered Rod Stewart feat/Cher As Time Goes By...The Great American Songbook Volume II 19 All About That Bass The Koi Boys The Koi Boys 20 Beyond the Sea Wayne Johnston The Cabaret Club 21 It's Getting Better Mama Cass Mama Cass 22 I Feel the Earth Move Carole King The Essential Carole King 23 The Best Is Yet to Come Tony Bennett Tony Bennett Celebrates 90 24 Dream A Dream Bic Runga Close Your Eyes 25 Love Me Tender Barb Jungr Love Me Tender 26 To All The Girls I've Loved Before Julio Iglesias Julio Iglesias - The Greatest Hits 27 Leaving on a Jet Plane Brothers3 and Mum Favourites 28 Careless Whisper Julie Anthony This is It 29 For the Good Times Frankie Danell An Evening with Frankie Danell 30 I've Got To See You Again Norah Jones Come Away With Me 31 Three-Quarter Blues Simon Tedeschi Gershwin Take Two.