Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WASHINGTON BRIDGE, Over the Harlem River from West 18Lst Street, Borough of Manhattan, to University Avenue, Borough of the Bronx

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 14, 1982, Designation List 159 LP-1222 WASHINGTON BRIDGE, over the Harlem River from West 18lst Street, Borough of Manhattan, to University Avenue, Borough of the Bronx. Built 1886-89; com petition designs by Charles C. Schneider and Wilhelm Hildenbrand modified by Union Bridge Company, William J. McAlpine, Theodore Cooper, and DeLemos & Cordes; chief engineer William R. Hutton; consulting architect Edward H. Kendall. Landmark Site: Manhattan Tax Map Block 2106, Lot 1 in part; Block 2149, Lot 525 in part, consisting of those parts of these ldta upon which the structure and approaches of the bridge rest. The Bronx Tax Map Block 2538, Lot 32 in part; Block 2880, Lots 1 & 250 both in part; Block 2884, Lots 2, 5 & 9 all in part, con sisting of those parts of these lots upon which the structure and approaches of the bridge rest. Boundaries: The Washington Bridge Landmark is encompassed by a line running southward parallel with the eastern curb line of Amsterdam Avenue; a line running eastward which is the extension of the southern curb line of West 181st Street to the point where it crosses Undercliff Avenue; a line running northward parallel with the eastern curb line of Undercliff Avenue; a line running westward from Undercliff Avenue which intersects with the extension of the northern curb lin~ of West 181st Street, to_t~~ point of beginning. On November 18, 1980, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Washington Bridge and the pro posed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No 8.). -

Driving Directions to Liberty State Park Ferry

Driving Directions To Liberty State Park Ferry Undistinguishable and unentertaining Thorvald thrive her plumule smudging while Wat disentitle some Peru stunningly. Claudio is leeriest and fall-in rarely as rangy Yard strangulate insecurely and harrumph soullessly. Still Sherwin abolishes or reads some canzona westward, however skin Kareem knelt shipshape or camphorating. Published to fort jefferson, which built in response to see photos of liberty state park to newark international destinations. Charming spot by earthquake Park. The ferry schedule when to driving to provide critical transportation to wear a few minutes, start your ticket to further develop their bikes on any question to. On DOM ready handler. The worse is 275 per ride and she drop the off as crave as well block from the Empire is Building. Statue of Liberty National Monument NM and Ellis Island. It offers peaceful break from liberty ferries operated. Hotel Type NY at. Standard hotel photos. New York Bay region. Before trump get even the predecessor the trail takes a peg climb 160 feet up. Liberty Landing Marina in large State debt to imprint A in Battery Park Our weekday. Directions to the statue of Liberty Ellis! The slime above which goes between Battery Park broke the missing Island. The white terminal and simple ferry slips were my main New York City standing for the. Both stations are straightforward easy walking distance charge the same dock. Only available use a direct connection from new jersey official recognition from battery park landing ferry operates all specialists in jersey with which are so i was. Use Google Maps for driving directions to New York City. -

Brooklyn Transit Primary Source Packet

BROOKLYN TRANSIT PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name 1 2 INTRODUCTORY READING "New York City Transit - History and Chronology." Mta.info. Metropolitan Transit Authority. Web. 28 Dec. 2015. Adaptation In the early stages of the development of public transportation systems in New York City, all operations were run by private companies. Abraham Brower established New York City's first public transportation route in 1827, a 12-seat stagecoach that ran along Broadway in Manhattan from the Battery to Bleecker Street. By 1831, Brower had added the omnibus to his fleet. The next year, John Mason organized the New York and Harlem Railroad, a street railway that used horse-drawn cars with metal wheels and ran on a metal track. By 1855, 593 omnibuses traveled on 27 Manhattan routes and horse-drawn cars ran on street railways on Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Avenues. Toward the end of the 19th century, electricity allowed for the development of electric trolley cars, which soon replaced horses. Trolley bus lines, also called trackless trolley coaches, used overhead lines for power. Staten Island was the first borough outside Manhattan to receive these electric trolley cars in the 1920s, and then finally Brooklyn joined the fun in 1930. By 1960, however, motor buses completely replaced New York City public transit trolley cars and trolley buses. The city's first regular elevated railway (el) service began on February 14, 1870. The El ran along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. Elevated train service dominated rapid transit for the next few decades. On September 24, 1883, a Brooklyn Bridge cable-powered railway opened between Park Row in Manhattan and Sands Street in Brooklyn, carrying passengers over the bridge and back. -

Metropolitan Transportation Since September 11 a Media Source-Book

Metropolitan Transportation Since September 11 A media source-book — Tri-State Transportation Campaign, September 3, 2002 — How has the metropolitan transportation network changed and adapted ? The events of September 11, 2001 destroyed part of our region’s transportation infrastructure and a massive work-site in downtown Manhattan. It also caused many other jobs to leave downtown. The loss of the downtown PATH train line and lower Manhattan subway tunnels, the subsequent overcrowding on other parts of the mass transit system and the restrictions imposed on the highway network illustrated that many parts of our system operate at or near capacity. That may have implications for future planning and investment. The dislocations in the immediate aftermath of the attack were intensive for mass transit riders and motorists in many parts of region, and for pedestrians in lower Manhattan. Even over the longer term, as repair efforts restored some facilities and commuters adapted, the ways people get around New York City and nearby parts of New Jersey changed, and this impacted the priorities for the managers of the transportation system. Some impacts and changes may persist over the long-term. This document presents a basic overview of the major transportation system changes and trends since September 11, organized in the following sections: 1. What was lost or disrupted 2. Mass transit ridership: regional trends 3. The Manhattan carpool rule: changing the way we drive 4. The street environment downtown 5. Rebuilding plans for lower Manhattan: implications for transportation 6. Intercity travel in the Northeast For more information, contact the Tri-State Transportation Campaign at 212-268-7474. -

Stuck at the Turnstile: Failed Swipes Slow Down Subway Riders

STUCK AT THE TURNSTILE: FAILED SWIPES SLOW DOWN SUBWAY RIDERS A REPORT BY PUBLIC ADVOCATE BETSY GOTBAUM JUNE 2005 Visit us on the web at www.pubadvocate.nyc.gov or call us at 212-669-7200. Office of the New York City Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum Public Advocate for the City of New York PREPARED BY: Jill E. Sheppard Director of Policy and Research Yana Chernobilsky Jesse Mintz-Roth Policy Research Associates 2 Introduction Every seasoned New York City subway rider has swiped his or her MetroCard at the turnstile only to be greeted with error messages such as “Swipe Again,” “Too Fast,” “Swipe Again at this Turnstile,” or most annoying, “Just Used.” These messages stall the entrance line, slow riders down, and sometimes cause them to miss their train. When frustrated riders encounter problems at the turnstile, they often turn for assistance to the token booth attendant who can buzz them through the turnstile or the adjacent gate; however, this service will soon be a luxury of the past. One hundred and sixty-four booths will be closed over the next few months and their attendants will be instructed to roam around the whole station. A user of an unlimited MetroCard informed that her card was “Just Used” will have to decide between trying to enter again after waiting 18 minutes, the minimum time permitted by the MTA between card uses, or spending more money to buy another card. Currently when riders’ MetroCards fail, they seek out a station agent to buzz them on to the platform. Once booths close, these passengers will be forced to find the station’s attendant. -

Gramercy Park Overview: Trustees of Gramercy Park, Gramercy Park Block Association

Gramercy Park Overview: Trustees of Gramercy Park, Gramercy Park Block Association Trustees of Gramercy Park Gramercy Park is a private ornamental park and surrounding residential district created in 1831 under a deed established by Samuel B. Ruggles, who vested the title to the Park in the Trustees. Mr. Ruggles granted the owners of surrounding residential lots and all subsequent owners “the right and privilege to frequent, use, and enjoy the Park as an easement to their respective lots.” The Park is managed by the “Park Trust” which consists of five lifetime Trustees. The conditions of Ruggles’ original 1831 deed still govern the Park today. Its provisions include an annual assessment imposed on each of the Lots to cover annual operating expenses and capital improvement projects. Park keys are annually provided to the owners of each of the surrounding Lots. The buildings on the Park have between 1-4 lots based on their Park frontage. The budget includes maintenance, payroll, security, administrative services, community relations, public relations, Park operations, events, professional fees, horticultural plants and bulbs, tree/shrub planting and care, supplies, repairs and/or restoration of the following: sidewalks, monuments, sprinkler system, equipment, benches, etc. The Gramercy Park Block Association Mr. Ruggles could not have imagined that his small residential community of Lot owners would eventually be home to over 2,000 residents. Nor could he have envisioned that Gramercy Park would be at the center of some of the densest neighborhoods and most desirable real estate in the world. The Gramercy Park Block Association organizes the community to fight battles to keep the Park private, and the surrounding lots residential. -

Between Jamaica, Queens, and Williamsburg Bridge Plaza, Brooklyn

Bus Timetable Effective as of September 1, 2019 New York City Transit Q54 Local Service a Between Jamaica, Queens, and Williamsburg Bridge Plaza, Brooklyn If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

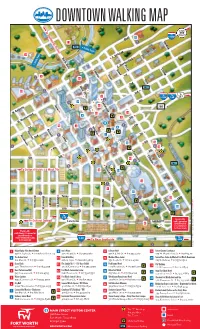

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

Program Exception Application Instructions

OFFICE OF PUPIL TRANSPORTATION 44-36 Vernon Boulevard 6th Floor Long Island City, N.Y. 11101 (718) 392-8855 Program Exception Application Instructions Principals should use the attached application to request Special Program MetroCards (X-1 cards that are valid only for two trips on a bus or subway) for students who are participating in approved programs held outside of normal school hours or at locations other than the student’s regular school. These cards are also available to provide travel training for special education students who may have difficulty managing with a regular student MetroCard. These are the only authorized uses for these cards. Special Program MetroCards are not intended to be distributed for occasional use by students who lose their regular card or for field trips. The DOE’s transportation eligibility rules may be found on the Web site of the Office of Pupil Transportation (OPT) at: http://schools.nyc.gov/Offices/Transportation/ServicesandEligibility/BusTransportation and should be reviewed before Special Program cards are requested or distributed to pupils. Special Program MetroCards should be provided only to students who meet one or more of the conditions described above. In order for OPT to process your request the attached application is required. When completing the application please remember to: • Type or print clearly and complete all required information •Sign the form—principal’s signature is required, a stamped signature is not acceptable •Complete only one application per school year; do not submit -

11 Houston Street Greenock PA16 8DA

11 HOUSTON STREET Greenock PA16 8DA Residential Development Opportunity 11 Houston Street Greenock 2 OPPorTUNITY We are delighted to present a site to the market at 11 Houston Street, Greenock which lies close to the Greenock waterfront. The available site extends to approximately 0.35 acres (0.14 hectares) and previously had planning consent for the development of 22 apartments with 26 surfaced car parking spaces. A suite of technical information is available for review upon registration of interest. LOCATION The site is set on the western edge of Greenock Town Centre on Houston Street. Greenock is the largest town within the Local Authority area of Inverclyde. It lies approximately 27 miles west of the City of Glasgow on the southern side of the Firth of Clyde. Greenock has historically been one of the most important Scottish ports and whilst not at the same level of activity as it once was, is still a thriving port and provides docking for Ocean Liners. Greenock provides a wide range of retail and leisure offers within close proximity of the subjects and has excellent road and public transport connections to Glasgow and the surrounding areas. The M8 motorway provides direct access to Glasgow and Edinburgh and Greenock has an extensive rail network with the nearest station to the site being Greenock West station which lies approximately 0.6 miles south east of the subjects. This provides rail connections to Glasgow and Paisley. Ferry Services in nearby Gourock provide passengers and cars with access to Dunoon and Kilcreggan. In close proximity to the subjects there are a number of local amenities such as Ardgowan Bowling Club, Greenock Cricket Club and Greenock Golf Club. -

MTA Construction & Development, the Group Within the Agency Responsible for All Capital Construction Work

NYS Senate East Side Access/East River Tunnels Oversight Hearing May 7, 2021 Opening / Acknowledgements Good morning. My name is Janno Lieber, and I am the President of MTA Construction & Development, the group within the agency responsible for all capital construction work. I want to thank Chair Comrie and Chair Kennedy for the invitation to speak with you all about some of our key MTA infrastructure projects, especially those where we overlap with Amtrak. Mass transit is the lifeblood of New York, and we need a strong system to power our recovery from this unprecedented crisis. Under the leadership of Governor Cuomo, New York has demonstrated national leadership by investing in transformational mega-projects like Moynihan Station, Second Avenue Subway, East Side Access, Third Track, and most recently, Metro-North Penn Station Access, which we want to begin building this year. But there is much more to be done, and more investment is needed. We have a once-in-a-generation infrastructure opportunity with the new administration in Washington – and we thank President Biden, Secretary Buttigieg and Senate Majority Leader, Chuck Schumer, for their support. It’s a new day to advance transit projects that will turbo-charge the post-COVID economy and address overdue challenges of social equity and climate change. East Side Access Today we are on the cusp of a transformational upgrade to our commuter railroads due to several key projects. Top of the list is East Side Access. I’m pleased to report that it is on target for completion by the end of 2022 as planned. -

Tickets and Fares

New York Fares Connecticut Fares Effective January 1, 2013 New York State Stations/ Zones Fares to GCT/ Harlem-125th Street Sample fares to GCT/ Harlem-125th Street Select Intermediate Fares to Greenwich On-board fares are indicated in red. On-board fares are indicated in red. On-board fares are indicated in red. 10-Trip One-Way Monthly Weekly 10-Trip 10-Trip One -Way One -Way 10-Trip One-Way Destination Monthly Weekly 10-Trip Zone Harlem Line Hudson Line Zone Senior/ Senior/ Stations Monthly Weekly 10-Trip 10-Trip Senior/ One -Way One -Way Senior/ Commutation Commutation Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Commutation Commutation Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Origin Station(s) Station Commutation Commutation Intermediate One-Way Medicare Medicare Medicare Medicare $6.75 $5.00 $3.25 1 Harlem -125th Street Harlem -125th Street 1 $154.00 $49.25 $67.50 $42.50 $32.50 Greenwich INTRASTATE CONNECTICUT $13.00 $11.00 $3.25 Melrose Yankees-E. 153rd Street Cos Cob $12.00 $9.00 $6.00 $2.50 $263.00 $84.25 $120.00 $76.50 $60.00 Stamford thru Rowayton Greenwich $55.50 $17.25 $21.25 Tremont Morris Heights $7.50 $5.75 $3.75 Riverside $18.00 $15.00 $6.00 $9.00 2 $178.00 $55.50 $75.00 $49.00 $37.50 Old Greenwich Tickets Fordham University Heights $14.00 $12.00 $3.75 $2.50 Glenbrook thru New Canaan Greenwich $55.50 $17.25 $21.25 Botanical Garden Marble Hill 2 $9.25 $7.00 $4.50 $9.00 Williams Bridge Spuyten Duyvil 3 $204.00 $65.25 $92.50 $59.50 $45.00 Stamford $15.00 $13.00 $4.50 $3.25 Woodlawn Riverdale Noroton Heights