Narrating Animal Trauma in Bulgakov and Tolstoy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRITTANY SPANIEL (Epagneul Breton) 2

FEDERATION OF CYNOLOGY FOR EUROPE ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ ПО КИНОЛОГИЯ ЗА ЕВР ОПА 05.05.2003/EN FCE-Standard № 7-95 BRITTANY SPANIEL (Epagneul Breton) 2 TRANSLATION: John Miller and Raymond Triquet. ORIGIN: France. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD: 25.03.2003. UTILIZATION: Pointing dogs. FCE-CLASSIFICATION : Group 7 Pointing Dogs and Setters. Section 1.2 Continental Pointing Dogs, Spaniel type. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: Of French origin and more precisely, from the centre of Brittany. At present, in first place numerically among French sporting breeds. Probably one of the oldest of the spaniel type dogs, improved at the beginning of the 20th century by diverse outcrosses and selections. A draft of a breed standard drawn up in Nantes in 1907 was presented and adopted at the first General Assembly held in Loudéac (in former Côtes du Nord department, now Côtes d’Armor), June 7, 1908. This was the first standard of the « Naturally Short-Tailed Brittany Spaniel Club ». GENERAL APPEARANCE: Smallest of the pointing breeds. The Brittany spaniel is a dog with a Continental spaniel-type head (braccoïde in French) and a short or inexistent tail. Built harmoniously on a solid but not weighty frame. The whole is compact and well-knit, without undue heaviness, while staying sufficiently elegant. The dog is vigorous, the look is bright and the expression intelligent. The general aspect is « COBBY » (brachymorphic), full of energy, having conserved in the course of its evolution the short-coupled model sought after and fixed by those having recreated the breed. FCE-St. № 7-95/05.05.2003 3 IMPORTANT PROPORTIONS: • The skull is longer than the muzzle, with a ratio of 3 : 2. -

Companion Animal Intermediate Leader's Page.Indd

[INTERMEDIATE LEADER’S PAGE] Explore classifi cation of dog breeds Learn important facts about rabbits Expand companion animal vocabulary Develop mathematical skills Increase technology skills W139A Complete a service project Pets are important parts of our lives. However, they require much Gain an awareness about cat communication responsibility on your part as the owner and depend on you to take proper care of them. Some of the new skills that you can learn in Responsibility the 4-H Companion Animal project are listed on the left. Check your favorites and then work with your 4-H leaders and parents to make a 4-H project plan of what you want to do and learn this year. Cats use many of their body parts to communicate with us. The ears, eyes, head, whiskers, tail and paws are used by cats to express themselves. They also use their "voices" to tell us if they are happy or mad. Study the actions below. Circle the happy face or mad face to show how the feline is feeling. The cat is purring. The cat has moved his/her ears forward and up. The whiskers appear to be bristled. The cat’s ears are fl attened back against its head. The cat “chirps.” The cat hisses. The cat’s tail is bushed out. The cat is thumping his/her tail. The cat is kneeding his or her paws. The cat’s eyes are partially closed. The cat rubs his/her head against the leg of your pants. The cat growls. THE UNIVERSITY of TENNESSEE The American Kennel Club (AKC) divides dogs into seven different breed groups. -

Game Management in the Czech Republic Game Management in the Czech Republic 3

Petr Šeplavý Ing. Jaroslav Růžička Ing. Jiří Pondělíček, Ph.D. GAME MANAGEMENT IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC GAME MANAGEMENT IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC 3 Natural conditions The Czech Republic is located in Central Europe and it is a member of the European Union. The total area of the Czech Republic is 78,866 km2. The Czech Republic borders with Ger- many, Poland, Slovakia and Austria. The landscape is mainly for- med by uplands and highlands. The area of the Czech Republic is surrounded by mountains, which slope down to lowlands along the main rivers (Labe, Vltava, Morava). The Třeboň’s basin is the largest basin with the area 1,360 km2. Erosion helped to form bizarre rocky formations called “rock towns” which could be seen especially in the northeast Bohemia. The Czech Repub- lic is located on the main European water divide. Total precipi- tation amounts to 693 mm. One third of that amount flows to three seas. The longest river is called Vltava and its length is 433 km. Vltava and Labe together create the longest river road of the Czech Republic with the length of 541 km. There are many artificial dams in the Czech Republic. Most of them were built during the 20th century. Dam reservoirs are used in flood prevention, as sources of the energy and vacation venues. Most dams are on the Vltava River (so-called the Vltava Cascade). The largest dam is Lipno with the area of 4,870 hectares. Ponds are the phenomenon of the Czech countryside. They were built from the 12th century, primarily for the purpose of fish bree- ding. -

Draft for a Discussion on Basic Genetics.Pdf

2 Foreword. “Mens sana in corpore sano” : a healthy mind in a healthy body. The health of the Rottweiler, worldwide, lies close to our heart and is embedded in the Constitution of the International Federation of Rottweilerfriends (IFR). It’s reference to the health of all breeding dogs, implies that the Federation and its Memberclubs must pay particular attention to genetic disorders. For the Rottweiler, Hip Dysplasia (HD) and Elbow Dysplasia (ED) were the first disorders that worldwide led to regulations meant to diminish the genetic affection of the breed. The measures that were taken by breed clubs and/or kennelclubs, mostly by excluding the dogs that are affected by the disease from breeding, have proven to be quite effective, although not enough to completely eliminate the genetic factor and remove it from the genepool Still they have helped to limit the number of affected dogs and to avoid a lot of suffering. In this brochure you will find a brief review of just a few of the genetic diseases that are said to have entered the Rottweiler’s genepool. 1 The list is not new, nor the particular diseases on it. Even the way of approaching the problem is known for a long time and was amongst others confirmed in the International Breeding Strategies of the FCI that were approved in 2009. Indeed, not just for the Rottweiler but for many other breeds too, cynology has sounded a loud alarm concerning an ever more reduced genetic diversity among certain canine breeds, causing not only extreme phenotypes (2) but also physical and health problems. -

Journal of Pads

№ 36 November 2013 From the Publisher... Dear members of PADS and readers of our Journal, JOURNAL In this issue we publish an article by Alexander Vlasenko about the evolutionary formation of aboriginal dog breeds in Southeast Asia. Information he presents indicates that cynology, as a scientific field of research, still remains almost untouched by biologists to unravel the origins of the domesticated dog. Do they have enough time before the world of aboriginal dogs disappears under the pressures of modern life? We also publish an article submitted by Perikles Kosmopoulos and Evangelos Geniatakis, who are natives of Crete and breed Cretan Hounds. They love their of the International Society for ancient breed and have dedicated much of their life to its the preservation. Preservation of Primitive Sincerely yours, Vladimir Beregovoy Aboriginal Dogs Secretary of PADS, International 2 To preserve through education……….. In This Issue… On the problem of the origin of the domesticated dog and the incipient (aboriginal) formation of breeds On the problem of the origin of the domesticated dog and Alexander Vlasenko the incipient (aboriginal) formation of breeds ..................... 4 Moscow, Russia The Cretan tracker (or Kritikos Ichnilatis). Study of a In search for an answer to the question about the living legend......................................................................... 47 ancestors of the domesticated dog and where and when it LIST OF MEMBERS ......................................................... 70 originated, it is not enough to use an approach from the standpoint of one branch of biological science, such as genetics, morphology, comparative anatomy or ethology. Controversial results of genetic investigations and paleontological findings require the use of a complex analysis of obtained data. -

Interspecies Affection and Military Aims Was There a Totalitarian Dog?

Interspecies Affection and Military Aims Was There a Totalitarian Dog? XENIA CHERKAEV Academy for International and Area Studies, Harvard University, USA ELENA TIPIKINA Borey Art Center, St. Petersburg, Russia Abstract The image of totalitarianism is central to liberal ideology as the nefarious antithe- sis of free market exchange: the inevitable outcome of planned economies, which control their subjects’ lives down to the most intimate detail. Against this image of complete state control, the multispecies ethnography of early Soviet institutions gives us a fortuitous edge to ask how centrally planned economies structure the lives of those actors whose biosocial demands can be neither stamped out nor befuddled by propaganda. In this article we exam- ine the institutions of the Stalinist state that could have created the totalitarian service dog: institutions that planned the distribution, raising, and breeding of family dogs for military service. Our narrative begins with a recently discovered genealogical document, issued to a German Shepherd bred by plan and born during the World War II Leningrad Blockade. Read- ing this document together with service-dog manuals, Soviet physiological studies, archival military documents, and autobiographical narratives, we unravel the history of Leningrad’s early Soviet military-service dog husbandry program. This program, we argue, relied on a particular distinction of public and private: at once stimulating affectionate interspecies bonds between dogs and their handlers and sequestering those relationships from the image of rational, scientifically objective interspecies communication. This reduction of human-dog relations to those criteria that could be scientifically studied and centrally planned yielded tangible results: it allowed the State’s dog husbandry program to create apparently unified groups of dogs and dog handlers and to successfully mobilize these groups for new military tasks, like mine detection, during World War II. -

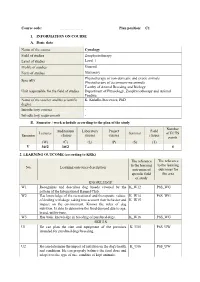

C1 1. INFORMATION on COURSE A. Basic Data Name of The

Course code: ………………. Plan position: C1 1. INFORMATION ON COURSE A. Basic data Name of the course Cynology Field of studies Zoophysiotherapy Level of studies Level 1 Profile of studies General Form of studies Stationary Physiotherapy of non-domestic and exotic animals Specialty Physiotherapy of accompanying animals Faculty of Animal Breeding and Biology Unit responsible for the field of studies Department of Physiology, Zoophysiotherapy and Animal Feeding Name of the teacher and his scientific K. Kirkiłło-Stacewicz, PhD degree Introductory courses - Introductory requirements - B. Semester / week schedule according to the plan of the study Number Auditorium Laboratory Project Field Lectures Seminar of ECTS Semester classes classes classes classes points (W) (Ć) (L) (P) (S) (T) V 30/2 30/2 4 2. LEARNING OUTCOME (according to KRK) The reference The reference to the learning to the learning No. Learning outcomes description outcomes of outcomes for specific field the area of study KNOWLEDGE W1 Recognizes and describes dog breeds covered by the K_W12 P6S_WG pattern of the International Kennel Club. W2 Has knowledge of the recreational and therapeutic values K_W14 P6S_WG of dealing with dogs, taking into account their behavior and K_W15 impact on the environment. Knows the rules of dog nutrition. Is able to determine the food demand due to age, breed, utility type. W3 Has basic knowledge in breeding of purebred dogs. K_W16 P6S_WG SKILLS U1 He can plan the size and equipment of the premises K_U05 P6S_UW intended for purebred dogs breeding. U2 He can determine the impact of nutrition on the dog's health K_U06 P6S_UW and condition. -

Cynology: the Study of Dogs with Brandon Mcmillan Ologies Podcast May 28, 2018

Cynology: The Study of Dogs with Brandon McMillan Ologies Podcast May 28, 2018 Heeeey! It’s ol’ Poddy von DadWard with another episode of Ologies. Hi, it’s Alie Ward. So, quick question, who doesn’t love a dog? If you are like, [nyeh] me, then just go! Shoo! Go on, git! That’s right, this episode is all about the beasts that live on your couch; your, just drooling, very very hairy best friend. I love dogs so much I’ve cried about it. I’ve cried about it! Probably so have you. So, before we get really into it, I just want to say a quick thanks to all the folks on Patreon, who support this show, Patreon.com/Ologies. Also, to all the folks who cover their bods with t-shirts and such, all available at Ologiesmerch.com. Y’all support the show. Thank you for zero-dollars- supporting just by reviewing on iTunes or Stitcher. So, as I write this on a holiday weekend, hey, Ologies is number fifteen in the Apple Podcasts Science Charts, which is huge, and crazy, and wonderful. Also, you know, like a dog tearing through your bathroom garbage and eating things, I read all of your reviews, like a fucking creep. And just to prove I read them, I read you one every week. This week’s, Rich the Beach says: This is fast becoming one of my favorite podcasts. It’s hard to imagine that you can get so into a podcast about trees or bees, but this gets me every time. -

Political Animals: Representing Dogs in Modern Russian Culture Studies in Slavic Literature and Poetics

Political Animals: Representing Dogs in Modern Russian Culture Studies in Slavic Literature and Poetics Editors O.F. Boele S. Brouwer J.M. Stelleman Founding Editors J.J. van Baak R. Grübel A.G.F. van Holk W.G. Weststeijn VOLUME 59 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sslp Political Animals: Representing Dogs in Modern Russian Culture By Henrietta Mondry LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: the monument to Pavlov’s dog in St Petersburg (1935), photographed by Peter Campbell. On the initiative of Pavlov a monument to a dog was installed near the department of Physiology, in the garden of the Institute of experimental medicine, to pay a tribute to the dog’s unselfish service to biological science. Sculptor: Bespalov. Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930710 issn 0169-0175 isbn 978-90-42-03902-5 (paperback) isbn 978-94-01-21184-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill nv provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, ma 01923, usa. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

BLOODHOUND (Chien De Saint-Hubert ) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs Jeans-Brown, Revised by Mr R

FEDERATION OF CYNOLOGY FOR EUROPE ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ ПО КИНОЛОГИЯ ЗА ЕВР ОПА 12.07.2002/EN FCE-Standard № 6-84 BLOODHOUND (Chien de Saint-Hubert ) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs Jeans-Brown, revised by Mr R. Pollet and R. Triquet. ORIGIN: Belgium. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE ORIGINAL VALID STANDARD: 13.03.2001. UTILISATION: Scent hound for large game venery, service dog, tracking dog and family dog. It was and it must always remain a hound which due to its remarkable sense of smell is foremost a leash hound, often used not only to follow the trail of wounded game as in the blood scenting trials but also to seek out missing people in police operations. Due to its functional construction, the Bloodhound is endowed with great endurance and also an exceptional nose which allows it to follow a trail over a long distance and difficult terrain without problems. FCE-CLASSIFICATION : Group 6 Scent hound and related breeds. Section 1 Scent hounds. 1.1 Large sized hounds. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: Large scent hound and excellent leash hound, with very ancient antecedents. For centuries it has been known and appreciated for its exceptional nose and its great talent for the hunt. It was bred in the Ardennes by the monks of the Abbaye de Saint-Hubert. It is presumed to descend from black or black and tan hounds hunting in packs which were used in the 7th century by the monk Hubert, who was later made a bishop and who when canonised became the patron saint of hunters. These big scent hounds spread throughout the Ardennes, due to the presence of large game, sheltering in the widespread forests of the region. -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links -

Comparison Various Body Measurements of Aksaray Malakli and Kangal Dogs

Journal of Istanbul Veterınary Scıences Comparison various body measurements of Aksaray Malakli and Kangal Dogs Yusuf Ziya Oğrak1*, Nurşen Öztürk2, Dilara Akın2, Mustafa Özcan2 1 Cumhuriyet University, Veterinary Faculty, Department of Animal Breeding and Husbandry, Research Article Sivas/Turkey. 2 Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Veterinary Faculty, Department of Animal Volume: 2, Issue: 3 Breeding and Husbandry, İstanbul/Turkey. December 2018 Pages: 86-91 ABSTRACT This study was conducted to compare and evaluate some body measurements of Kangal Dog and Aksaray Malakli Dog breeds. The study group consist of dogs with an age range from 2 to 5 years. Samples for Kangal dogs were obtained from Sivas and for Aksaray Malakli dogs from Aksaray province. Observations from ten dogs from both species (5 male and 5 female), in total 20 adult dogs were used for this study. Some of the morphological characteristics as black mask around the head, cream fur colour and holding spiral tail were found evident for Kangal dogs while in all Aksaray Malakli dogs the head and body size, thimbleful black mask around the head, and 6th nail existence were determined as descriptive differences between the genotypes. While the effect of gender on muzzle length, body index and bone index was not found to be significant, it was found significant for other body measurements. The rump lengths in male Aksaray Malakli dogs were significantly larger than male Kangal dogs (P<0.001). However, this trait was not significant for female dogs. This can be associated with the significant interaction between breed and gender (P<0.01). Body index also showed the same trend.