Parrying Daggers and Poniards By: Leonid Tarassuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiere Props • Hollyw Ood a Uction Extra Vaganza VII • Sep Tember 1 5

Premiere Props • Hollywood Auction Extravaganza VII • September 15-16, 2012 • Hollywood Live Auctions Welcome to the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza weekend. We have assembled a vast collection of incredible movie props and costumes from Hollywood classics to contemporary favorites. From an exclusive Elvis Presley museum collection featured at the Mississippi Music Hall Of Fame, an amazing Harry Potter prop collection featuring Harry Potter’s training broom and Golden Snitch, to a entire Michael Jackson collection featuring his stage worn black shoes, fedoras and personally signed items. Plus costumes and props from Back To The Future, a life size custom Robby The Robot, Jim Carrey’s iconic mask from The Mask, plus hundreds of the most detailed props and costumes from the Underworld franchise! We are very excited to bring you over 1,000 items of some of the most rare and valuable memorabilia to add to your collection. Be sure to see the original WOPR computer from MGM’s War Games, a collection of Star Wars life size figures from Lucas Film and Master Replicas and custom designed costumes from Bette Midler, Kate Winslet, Lily Tomlin, and Billy Joel. If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of our staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza V II live event and we look forward to seeing you on October 13-14 for Fangoria’s Annual Horror Movie Prop Live Auction. -

Records of the Medieval Sword Free

FREE RECORDS OF THE MEDIEVAL SWORD PDF Ewart Oakeshott | 316 pages | 15 May 2015 | Boydell & Brewer Ltd | 9780851155661 | English | Woodbridge, United Kingdom Records of the Medieval Sword by Ewart Oakeshott, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® I would consider this the definitive work on the development of the form, design, and construction of the medieval sword. Oakeshott was the foremost authority on the subject, and this work formed the capstone of his career. Anyone with a serious interest in European swords should own this book. Records of the Medieval Sword. Ewart Oakeshott. Forty years of intensive research into the specialised subject of the straight two- edged knightly sword of the European middle ages are contained in this classic study. Spanning the period from the great migrations to the Renaissance, Ewart Oakeshott emphasises the original purpose of the sword as an intensely intimate accessory of great significance and mystique. There are over photographs and drawings, each fully annotated and described in detail, supported by a long introductory chapter with diagrams of the typological framework first presented in The Archaeology of Weapons and further elaborated in The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. There are appendices on inlaid blade inscriptions, scientific dating, the swordsmith's art, and a sword of Edward Records of the Medieval Sword. Reprinted as part Records of the Medieval Sword Boydell's History of the Sword series. Records of the Medieval Sword - Ewart Oakeshott - Google книги Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. -

The European Bronze Age Sword……………………………………………….21

48-JLS-0069 The Virtual Armory Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by _____________________________ ____________________________ Patrick Feeney Jennifer Baulier _____________________________ Ian Fite February 18th 2013 Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: Higgins Armory, Arms and Armor, QR Code 1 Abstract This project explored the potential of QR technology to provide interactive experiences at museums. The team developed content for selected objects at the Higgins Armory Museum. QR codes installed next to these artifacts allow visitors to access a variety of minigames and fact pages using their mobile devices. Facts for the object are selected randomly from a pool, making the experience different each time the code is scanned, and the pool adapts based on artifacts visited, personalizing the experience. 2 Contents Contents........................................................................................................................... 3 Figures..............................................................................................................................6 Introduction ……………………………………………......................................................... 9 Double Edged Swords In Europe………………………………………………………...21 The European Bronze Age Sword……………………………………………….21 Ancient edged weapons prior to the Bronze Age………………………..21 Uses of European Bronze Age swords, general trends, and common innovations -

Outdoor& Collection

MAGNUM COLLECTION 2020 NEW OUTDOOR& COLLECTION SPRING | SUMMER 2020 early years. The CNC-milled handle picks up the shapes of the Magnum Collection 1995, while being clearly recognizable as a tactical knife, featuring Pohl‘s signature slit screws and deep finger choils. Dietmar Pohl skillfully combines old and new elements, sharing his individual shapes and lines with the collector. proudly displayed in showcases around the For the first time, we are using a solid world, offering a wide range of designs, spearpoint blade made from 5 mm thick quality materials and perfect craftsmanship. D2 in the Magnum Collection series, giving the knife the practical properties you can For the anniversary, we are very pleased that expect from a true utility knife. The knife we were able to partner once again with has a long ricasso, a pronounced fuller and Dietmar Pohl. It had been a long time since a ridged thumb rest. The combination of MAGNUM COLLECTION 2020 we had worked together. The passionate stonewash and satin finish makes the blade The Magnum Collection 2020 is special in designer and specialist for tactical knives scratch-resistant and improves its corrosion- many ways. We presented our first Magnum has designed more than 60 knives, among resistance as well. The solid full-tang build catalogue in 1990, followed three years later them the impressive Rambo Knife featured gives the Magnum Collection 2020 balance by the first model of the successful Magnum in the latest movie of the action franchise and stability, making it a reliable tool for any Collection series. This high-quality collector‘s with Sylvester Stallone. -

Legal Notice

Legal Notice Date: October 19, 2017 Subject: An ordinance of the City of Littleton, amending Chapter 4 of Title 6 of the Littleton Municipal Code Passed/Failed: Passed on second reading CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO ORDINANCE NO. 28 Series, 2017 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN DocuSign Envelope ID: 6FA46DDD-1B71-4B8F-B674-70BA44F15350 1 CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO 2 3 ORDINANCE NO. 28 4 5 Series, 2017 6 7 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN 8 9 AN ORDINANCE OF THE CITY OF LITTLETON, 10 COLORADO, AMENDING CHAPTER 4 OF TITLE 6 OF 11 THE LITTLETON MUNICIPAL CODE 12 13 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-008 amended C.R.S. §18-12-101 to remove the 14 definitions of gravity knife and switchblade knife; 15 16 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-088 amended C.R.S. §18-12-102 to remove any 17 references to gravity knives and switchblade knives; and 18 19 WHEREAS, the city wishes to update city code in compliance with these 20 amendments to state statute. 21 22 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF 23 THE CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO, THAT: 24 25 Section 1: Section 151 of Chapter 4 of Title 6 is hereby revised as follows: 26 27 6-4-151: DEFINITIONS: 28 29 ADULT: Any person eighteen (18) years of age or older. 30 31 BALLISTIC KNIFE: Any knife that has a blade which is forcefully projected from the handle by 32 means of a spring loaded device or explosive charge. 33 34 BLACKJACK: Any billy, sand club, sandbag or other hand operated striking weapon consisting, 35 at the striking end, of an encased piece of lead or other heavy substance and, at the handle end, a 36 strap or springy shaft which increases the force of impact. -

In the Court of Appeals of Iowa

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF IOWA No. 8-907 / 07-1450 Filed December 31, 2008 STATE OF IOWA, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. RAMON LAMONT PRICE, Defendant-Appellant. ________________________________________________________________ Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Polk County, Joel D. Novak, Judge. Price appeals from his first-degree and second-degree robbery convictions. AFFIRMED IN PART; SENTENCE VACATED IN PART. Mark C. Smith, State Appellate Defender, and David Adams, Assistant Appellate Defender, for appellant. Thomas J. Miller, Attorney General, Thomas S. Tauber, Assistant Attorney General, John P. Sarcone, County Attorney, and, Michael Hunter, Assistant County Attorney, for appellee. Considered by Vogel, P.J., and Mahan and Miller, JJ. 2 VOGEL, P.J. Ramon Price appeals from his convictions of one count of first-degree robbery in violation of Iowa Code sections 711.1 and 711.2 (2005) and two counts of second-degree robbery in violation of Iowa Code sections 711.1 and 711.3. Our review is for corrections of errors at law. Iowa R. App. P. 6.4. Price challenges the sufficiency of the evidence as to his first-degree robbery conviction arguing the State had failed to prove the two and one-eight inch pocket knife he was armed with was a dangerous weapon. “A person commits robbery in the first degree when, while perpetrating a robbery, the person purposely inflicts or attempts to inflict serious injury, or is armed with a dangerous weapon.” Iowa Code § 711.2. A dangerous weapon is any instrument or device designed primarily for use in inflicting death or injury upon a human being or animal, and which is capable of inflicting death upon a human being when used in the manner for which it was designed. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

THE HISTORY of the RAPIER the Culture and Construction of the Renaissance Weapon

THE HISTORY OF THE RAPIER The Culture and Construction of the Renaissance Weapon An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Robert Correa Andrew Daudelin Mark Fitzgibbon Eric Ostrom 15 October 2013 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen Abstract At the end of the Middle Ages, weapons began to be used not only on the battlefield, but for civilian use as well. The rapier became the essential self-defense weapon of the “Renaissance man.” This project explores the evolution and manufacture of the rapier through history. This cut-and-thrust sword was manufactured by artisans who had to develop new methods of crafting metal in order to make the thin, light blade both durable and ductile. To study this process, a rapier was constructed using classical methods. Upon the completion of the replica, its material properties were studied using a surface microscope. The project also included contributing to the WPI Arms and Armor website. ii Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Professor Diana Lados and Mr. Tom Thomsen for creating the Evolution of Arms and Armor Interactive Qualifying Project. Their guidance and assistance were invaluable throughout the project experience. A huge thanks also to Josh Swalec and Ferromorphics Blacksmithing. The expertise of Mr. Swalec and others at Ferromorphics was key to learning smithing techniques and using them to construct a replica of a rapier in the Renaissance style. Mr. Swalec opened the doors of his shop to us and was welcoming every step of the way. -

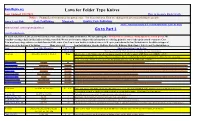

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Equipment.Htm Equipment

Taken from the Khemri website – published by ntdars http://grafixgibs.tripod.com/Khemri/equipment.htm Equipment Weapons Ankus(elephant goad) This is used to primarily herd elephants. It may be used as a spear, when charged and a staff in hth. Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: Strike first (only when charged), concussion Jambiya: The common curved dagger of araby. Everyone gets one free. Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: +1 enemy armor save Katar (punch dagger): It has a handle perpendicular to the blade and is used by punching with it. Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: -1 enemy armor save Scythe: Normally used to cut hay but works just as well to cut bodies Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: Cutting edge, Two Handed Cutlass: A regular sword but with a basket handle that can be used for a punch attack Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: Parry, extra punch attack if hit is successful Great Scimitar: This scimitar is commonly used by headsmen and is a large heavy version of a regular scimitar. Range: Close Combat; Strength: +2; Special Rules: two-handed, Strike last, Cutting edge Scimitar: This is a curved sword but tends to be sharper than a regular sword. Range: Close Combat; Strength: as user; Special Rules: parry, Cutting edge Bagh Nakh (tiger claws): Basically brass knuckles with spikes sticking out. Range: Close Combat; Strength: +1; Special Rules: -1 enemy armor save, pair, cumbersome Tufenk: this is a blowpipe that projects Greek fire about 10 feet causing burning damage. -

Product Information File at Sword Cold Steel Cinquedea Sword

Product information file at WWW.SWORDS24.EU Sword Cold Steel Cinquedea Sword Category: Product ID: 88CDEA Manufacturer: Cold Steel Price: 205.00 EUR Availability: Out of stock Cold Steel is a world known maker of knives, swords and other edged weapons and tools, all products are made of best available materials. Company was founded in 1980 by company president, Lynn C. Thompson. The company's products include fixed blade knives, folding knives, swords, machetes, tomahawks, kukris, blowguns, walking sticks, and other martial arts–related items. See it in our store. A wide, stiff cut and thrust blade that could be brought into play in confined spaces, and deliver a mortal wound! Our interpretation of the Cinquedea is made from expertly heat treated 1055 Carbon steel with a highly engraved guard and pommel, and a hand-carved rosewood grip. The Cinquedea is sold complete with a leather scabbard with engraved steel throat and chape. The Cinquedea [Ching-kwi-dey-uh] has held a long fascination for us here at Cold Steel. It gained popularity as the sidearm of choice for noblemen walking through the narrow alleyways and walled cities of Italy. A blade worn exclusively for civilian self-defense, it was essentially the precursor to the civilian side sword and the rapier – and yet, this instrument of personal protection seems to have owed much of its design to fashion as it did to the cut and thrust of mortal combat! Surviving examples of these unusual short handled and steeply tapered blades are often highly embellished and ornate. With etched or gilded blades and deep multiple fullers that border on jewelry rather than weaponry – but beneath the romanticisms of high renaissance fashion lay a tool made with purpose. -

Saugus Developer Casts Iron Into Plans for Old Mill Bet Made by GE’S Avia- Development, Test and Tion Division As a Whole

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2019 Saugus developer casts iron into STOP. Bus plans for old mill routes By Bridget Turcotte apartments and parking be- ITEM STAFF neath. Three of the units would changed be affordable. SAUGUS — The historic An of ce building at 228 Cen- for the Scott Mill property could soon tral St. would be torn down to be transformed into an Iron make room for 2,000 square Works-inspired community feet of commercial space. The Better where people can live, eat, and ground oor is proposed to be store their belongings. a cafe with additional commer- By Thomas Grillo, A $5 million mixed-use devel- cial space underneath. Bridget Turcotte, opment is proposed on Central The design of the develop- and Bella diGrazia ITEM STAFF Street beside 222 Central Stor- ment is inspired by neighboring age. A three-story apartment Saugus Iron Works, from the A new plan by the building would be constructed color scheme of red and black to MBTA could change how on the right of the old mill- match the Iron Works house to thousands of North Shore turned-storage facility with 26 the design of the chimney. residents get to work ev- one-bedroom, townhouse style eryday. apartments, eight two-bedroom SAUGUS, A3 The agency has pro- posed changes to more than ve dozen bus routes that promise to increase regularity and improve dependability. Dubbed the Better Bus Project, the T has out- lined 47 no-cost proposals to update and modernize 63 bus routes, including many on the North Shore. “We are looking to make changes that improve the reliability and frequency of our bus service,” said Wes Edwards, the MBTA’s assistant general manag- er of service development.