THOMAS-BENTLEY HOUSE (Madison House) HABS NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Brookeville, Maryland Became United States Capital for a Day

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2020 "Here all seems security and peace!": How Brookeville, Maryland Became United States Capital for a Day Lindsay R. Richwine Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Richwine, Lindsay R., ""Here all seems security and peace!": How Brookeville, Maryland Became United States Capital for a Day" (2020). Student Publications. 804. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/804 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Here all seems security and peace!": How Brookeville, Maryland Became United States Capital for a Day Abstract When the British burned Washington D.C. during the War of 1812, the city’s civilians and officials fledo t the surrounding countryside to escape the carnage. Fearful that the attack on the Capital could eventually spell defeat and worried for their city, these refugees took shelter in the homes and fields of Brookeville, Maryland, a small, Quaker mill town on the outskirts of Washington. These pacifist esidentsr of Brookeville hosted what could have been thousands of Washingtonians in the days following the attack, ensuring the safety of not only the people of Washington, but of President Madison himself. As hosts to the President, the home of a prominent couple stood in for the President’s House, and as the effective center of command for the government, the town was crowned Capital of the United States for a day. -

Fort Mchenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 67, folder “Fort McHenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON '!0: Jack Marsh FROM: PAUL THEIS a>f Although belatedly, attached is some material on Ft. McHenry which our research office just sent in ••• and which may be helpful re the July 4th speech. Digitized from Box 67 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library :\iE\10 R.-\~ D l. \I THE \\'HITE HOI.SE \L\Sllli"GTO:'\ June 23, 1975 TO: PAUL 'IHEIS FROM: LYNDA DURFEE RE: FT. McHENRY FOURTH OF JULY CEREMONY Attached is my pre-advance report for the day's activities. f l I I / I FORT 1:vlc HENRY - July 4, 1975 Progran1 The program of events at Fort McHenry consists of two parts, with the President participating in the second: 11 Part I: "By the Dawn's Early Light • This is put on by the Baltimore Bicentennial Committee, under the direction of Walter S. -

Baltimore, Maryland

National Aeronautics and Space Administration SUSGS Goddard Space Flight Center LANDSAT 7 science for a chanuinu world Baltimore, Maryland Baltimore Zoo '-~ootballStadium Lake Montebello -Patterson Park Fort McHenry A Druid Hill Park Lake -Camden Yards Inner Harbor - Herring Run Park National Aeronautics and Space Administration ZIUSGS Goddard Space Flight Center Landsat 7 science for a changing world About this Image For The Classroom This false color image of the Baltimore, MD metropolitan area was taken infrared band. The instrument images the Earth in 115 mile (183 The use of satellites, such as Landsat, provides the opportunity to study on the morning of May 28, 1999, from the recently launched Landsat 7 kilometer) swaths. the earth from above. From this unique perspective we can collect data spacecraft. It is the first cloud-free Landsat 7 image of this region, History about earth processes and changes that may be difficult or impossible to acquired prior to the satellite being positioned in its operational orbit. The The first Landsat, originally called the Earth Resources Technology collect on the surface. For example, if you want to map forest cover, image was created by using ETM+ bands 4,3,2 (30m) merged with the 15- Satellite (ERTS-I), was developed and launched by NASA in July 1972. you do not need nor want to see each tree. In this activity, students will meter panchromatic band. Using this band combination trees and grass are Subsequent launches occurred in January 1975 and March 1978. explore the idea that being closer is not necessarily better or more red, developed areas are light bluellight green and water is black. -

Every Act of Life

EVERY ACT OF LIFE Featuring: Terrence McNally, F. Murray Abraham, Lynn Ahrens, Jon Robin Baitz, Christine Baranski, Dominic Cuskern, Tyne Daly, Edie Falco, Stephen Flaherty, John Glover, Anthony Heald, John Benjamin Hickey, Sheryl Kaller, John Kander, Roberta Kaplan, Tom Kirdahy, Larry Kramer, Nathan Lane, Angela Lansbury, Paul Libin, Joe Mantello, Marin Mazzie, Audra McDonald, Peter McNally, Lynne Meadow, Rita Moreno, Jack O’Brien, Billy Porter, Chita Rivera, Doris Roberts, Don Roos, John Slattery, Micah Stock, Richard Thomas, John Tillinger, & Patrick Wilson, the plus the voices of Dan Bucatinsky, Bryan Cranston, & Meryl Streep. “Wonderful . I wasn’t prepared for the emotional release of Every Act Of Life.” – The Paper “Poignant, incredibly inspiring . indispensable.” – The Village Voice “Really entertaining and illuminating . Bravo. – Edge Media “Riveting and revealing.” – Entertainment Weekly “Staggering, heart-warming, and inspiring beyond words.” – Joyce DiDonato “I just loved it. One of the best films I have seen at the festival.” – Rex Reed Short Synopsis: Four-time Tony-winning playwright Terrence McNally’s six ground-breaking decades in the theatre, the fight for LGBTQ rights, triumph over addiction, the pursuit of love and inspiration at every age, and the power of the arts to transform society. Synopsis: The son of an alcoholic beer distributor in southern Texas, Terrence traveled the world as tutor to John Steinbeck's children (Steinbeck’s only advice was, "Don't write for the theater, it will break your heart”); suffered an infamous Broadway flop in 1965 at age 24; and went on to write dozens of groundbreaking plays and musicals about sexuality, homophobia, faith, the power of art, the need to connect, and finding meaning in every moment of life. -

Neighborhood NEWS

Neighborhood NEWS RUXTON-RIDERWOOD-LAKE ROLAND AREA IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION WINTER • 2014-15 Annual Meeting Highlights INSIDE by Jessica Paffenbarger children’s play area. And…we got a sneak peak at the concept plan for the proposed Lake Roland Education This year we had a full course of delights at our an- Center to be located near nual meeting. Our appetizer was Silent Night 1814 the Ranger Station. a 40 minute Meet-and-Greet with PAGE 3 candidates for the Maryland Senate Many were surprised to H and House of Delegates. Our main learn that our 500 acre Closeting Old course was a presentation about park is over half the size New Year’s Robert E. Lee Park – Past, Present of Central Park and boasts Resolutions and Future. And dessert was a brief two National Register of PAGE 4 business meeting including the Historic Places Districts Treasurer’s report, a written update (Lake Roland Historic H of the Association’s business for District and Bare Hills Mary Kate Tells It the year, a goodbye and thank you Historic District)! The Like It Is to retiring Board members and a land for the Park was PAGE 6 vote to elect new and second-term acquired from The Balti- H members to the Board. more Gunpowder Company Home Sales of Maryland (formerly Patrick Jarosinski, RRLRAIA Jeffrey Budnitz and Elise Butler present “Robert E PAGE 7 Lee Park – Past, Present and Future” The Bellona Gunpowder President, opened with welcom- Photo courtesy John Baer Company) in the 1850s ing comments and introduced our H by the City of Baltimore Lake Roland host, Reverend Arianne Weeks, and flooded to create a lake as a reservoir for the Education Center Rector of the Church of the Good Shepherd. -

Volume 5 Fort Mchenry.Pdf

American Battlefield Trust Volume 5 BROADSIDE A Journal of the Wars for Independence for Students Fort McHenry and the Birth of an Anthem Of all the battles in American history none is more With a war being fought on the periphery of the Unit- connected with popular culture than the battle of Fort ed States the British, under the influence of Admiral McHenry fought during the War of 1812. The British George Cockburn, decided to bring the war more di- attack on Fort McHenry and the rectly to America by attacking the large garrison flag that could be Chesapeake Region. The British seen through the early morning Navy, with Marines and elements mist, inspired Washington, DC of their army wreaked havoc along lawyer Francis Scott Key to pen the Chesapeake burning numer- what in 1931 would be adopted ous town and settlements. Howev- by Congress as our National An- er, Cockburn had two prizes in them, the Star-Spangled Ban- mind – Washington, DC and Bal- ner. The anthem is played be- timore, Maryland. Retribution for fore countless sports events the burning of York was never far from high school through the from his mind and what a blow he ranks of professional games. thought, would it be to American The story of the creation of the morale if he could torch the still Star-Spangled Banner is as developing American capital. Af- compelling as the story of the ter pushing aside a motley assort- attack on Baltimore. ment of American defenders of the approach to Washington, DC In 1812, a reluctant President at the battle of Bladensburg, Mar- James Madison asked Congress yland, Cockburn and his forces for a Declaration of War against entered the city and put the torch Great Britain. -

Engineers News Staff Who Maybe Never Knew What Kind of in That Area

years Vol. 72, #8/AUGUST 2014 For The Good & Welfare By Russ Burns, business manager Anniversary Celebration a HUGE success As we continue celebrating Local allowing us to have a last weekend CONTENTS 3’s 75 years of member representation, together with Local 3.” Congratulations, pin recipients ............ 4 I hope you pay special attention to Our thoughts and prayers go out the coverage in this edition of our to his family. Thomas exemplifies Hawaii endorsements ....................... 6 Diamond Anniversary Event held perfectly what a union member is. Fringe .......................................... 7 on June 28 at Six Flags Discovery He was proud of his career operating ATPA ............................................ 7 Kingdom in Vallejo, Calif. More than cranes and barges, and he wanted his Public Employee News ...................... 8 5,500 Local 3 members, own family to experience their families and his union family. I am Credit Union ................................. 10 friends spent the day glad that he got his wish. Rancho Murieta .............................. 11 watching the exclusive Good things happen Looking at Labor ............................ 12 Local 3 shows that when we come together. Safety ......................................... 13 included tigers, dolphins This is what unionism is. and sea lions, riding the Several recent successes Unit 12 ........................................ 13 rollercoasters and water have resulted because of Organizing .................................... 14 rides and enjoying the our solidarity. President How does Local 3 celebrate 75 years? ... 15 all-you-could-eat lunch. Obama signed the Water 75 years strong .............................. 19 Everyone I talked Resources Reform and District Reports .............................. 20 to said the event was Development Act in a success, including Retiree Richard Thomas enjoys June, which equates to Meetings and Announcements ............ -

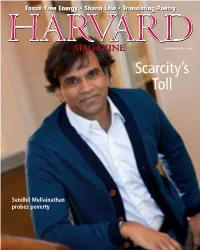

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

JFK Overpowers Walton Even the Waltons Aren't Safe from 30Th-Anniversary JFK Mania, As This Most Redundant of Sweeps Weeks Continues

TV PREVIEWS/MATT JFK overpowers Walton Even the Waltons aren't safe from 30th-anniversary JFK mania, as this most redundant of sweeps weeks continues. Good night, Jim-Bob, and let's all change the subject. First, though, comes Who Killed JFK: The Final Chap- ter? (**1/2, CBS, tonight at 9 ET/PT), CBS News' sixth ma- jor look into the subject, which makes you think maybe they (and we) should move on. But it can't be denied inter- est in the assns.sination remains strong. And Dan Rather, who was on the scene in 1963, re- cites a poll indicating most peo- ple think there was a conspira- cy of some sort, and 50% be- lieve the CIA was involved. USA What this says about the truth 0 isn't as clear as what it reveals C T about our cynical age. ODAY This two-hour CBS Reports devotes time to thumbnail his- • tories of the Kennedy presiden- FR cy and the Lee Harvey Oswald biography before settling down ID with its main topic: the tragic AY events of Nov. 22, With comput- , N er simulations of the ill-fated OV motorcade and a painstaking analysis of the Zapruder film, EMBER the clinical approach goes be- yorfd the merely graphic_ By Randy Tepper, CBS It's too grisly for words. REUNION: Richard Thomas, top, Michael Learned, left, and 1 One segment finds Rather Ralph Waite reprise Walton roles for 'Thanksgiving Reunion.' 9 and conspiracy-bashing author . 19 Gerald Posner (Case Closed) abundance of trite domestic repeatedly freeze-framing the crises are meant to reflect a 93 • Zapruder film at its bloodiest nation in decline, a malaise moment, analyzing trajectory symbolized by JFK's murder. -

Patterson Park Master Plan

) ) ) ) A MASTER PLAN FOR PA I I ERSON PARK IN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND J ) ) CITY OF BALTIMORE OEPARMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS CAPITAL PRo.JECTS AND PLANNING DIVISION JANUARY I 998 A MASTER PLAN FOR PAll ERSON PARK IN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND prepared in collaboration with: City of Baltimore Department of Recreation and Parks Capital Projects and Planning Division by: Rhodeside and Harwell, Incorporated Delon Hampton & Associates, Chartered A. Morton Thomas and Associates, Inc. Charles E. Beveridge, Historical Consultant • January 1998 • • • 0 0 a C) • • • • • • • . ... ······-· ···-· ··•·· .... ·--··· ·--·--·----·--------- CITY OF BALTIMORE OFFICE OF THE MAYOR 250 City Hall KURT 1.. SCIIMOKE, Mayor Baltimore, Maryland 21202 October 10,1997 Dear Reader: Baltimore has a rich legacy of open spaces and recreational facilities. For over 150 years, Patterson Park has served the diverse recreational needs of Southeast Baltimore and it remains the heart of its neighborhoods. I congratulate each of you who volunteered your time to participate in this master plan-- an important stage in mapping the park's future. This plan is a symbol of the kind of partnership between the City of Baltimore and its citizens which will protect our open space legacy for the future. 7:ely, lf::L~c~ • Mayor I DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION CITY OF BALTIMORE AND PARKS THOMAS V. OVERTON, ACTING DIRECTOR KURT L. SCHMOKE, Mayor I>R . RAI.I'II W E. JONES. JR . BUILDING .llllll Ensl Drive - Druid llill l'nrk, Bnhimurc, Mnrylnnd 21217 September 24, 1997 Dear Reader: Patterson Park is Baltimore's oldest and most intensively used green space. The residents of Southeast Baltimore have demonstrated their desire and commitment to sustaining the park as a centerpiece of their community through their active and vocal participation in the planning process that formed the basis for this master plan. -

Guide to the War of 1812 Sources

Source Guide to the War of 1812 Table of Contents I. Military Journals, Letters and Personal Accounts 2 Service Records 5 Maritime 6 Histories 10 II. Civilian Personal and Family Papers 12 Political Affairs 14 Business Papers 15 Histories 16 III. Other Broadsides 17 Maps 18 Newspapers 18 Periodicals 19 Photos and Illustrations 19 Genealogy 21 Histories of the War of 1812 23 Maryland in the War of 1812 25 This document serves as a guide to the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s library items and archival collections related to the War of 1812. It includes manuscript collections (MS), vertical files (VF), published works, maps, prints, and photographs that may support research on the military, political, civilian, social, and economic dimensions of the war, including the United States’ relations with France and Great Britain in the decade preceding the conflict. The bulk of the manuscript material relates to military operations in the Chesapeake Bay region, Maryland politics, Baltimore- based privateers, and the impact of economic sanctions and the British blockade of the Bay (1813-1814) on Maryland merchants. Many manuscript collections, however, may support research on other theaters of the war and include correspondence between Marylanders and military and political leaders from other regions. Although this inventory includes the most significant manuscript collections and published works related to the War of 1812, it is not comprehensive. Library and archival staff are continually identifying relevant sources in MCHC’s holdings and acquiring new sources that will be added to this inventory. Accordingly, researchers should use this guide as a starting point in their research and a supplement to thorough searches in MCHC’s online library catalog. -

Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection

MS-362 Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection Special Collections and Archives Wright State University Processed by: Rachel DeHart December 2007 Introduction The Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection was donated to Wright State University Special Collections and Archives by Richard Thomas in two installments during 2005 and December 2006. The collection is approximately 16 linear feet. The collection includes reports on Soviet military issues produced by the Center for Strategic Technology at Texas A&M University, as well as a variety of documents pertaining to the Cold War acquired from other sources; microfiche of translated reports and journals pertinent to the Cold War; and microfilm of a Soviet military journal. These materials were acquired by Dr. Thomas during his tenure as Head of the Center for Strategic Technology, and a number of the reports were written by him. The Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection spans the dates 1921 to 2006. However, the vast majority of materials date between the 1970s and 1990s. This collection documents U.S. intelligence on the strategic and technological position of the Soviet Union and other important regions during the Cold War. There are no restrictions on the use of the Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection. The Dr. Richard E. Thomas Collection is organized into 3 series: Series I: Reports Subseries A: Center for Strategic Technology Subseries B: Other Sources Series II: Microfiche Series III: Microfilm Biographical Sketch Richard Thomas is an expert in aerospace engineering, with knowledge and experience in the areas of aircraft aerodynamics, aerothermochemistry, advanced manufacturing systems, U.S. and foreign military technology, and foreign science and technology systems.