Gender, Race, Mobility and Performance in James Mcbride's the Good Lord Bird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Titles Highlighted in Yellow Were Purchased in 2018

Titles highlighted in yellow were purchased in 2018 Title Location/Author Year Airball: My Life in Shorts YA Harkrader 2006 Capote in Kansas: a drawn novel F Parks, Ande 2006 Deputy Harvey and the Ant Cow Caper JP Sneed, Brad 2006 John Brown, abolitionist: the man 973.7 Reynolds, David 2006 The Kansas Guidebook for Explorers 917.81 Penner, Marci 2006 The Moon Butter Route CS Yoho, Max 2006 Oceans of Kansas: a natural history of the western interior 560.457 Everhart, Michael 2006 sea Wildflowers and Grasses of Kansas: A Field Guide 582.13 Haddock, Michael 2006 The Youngest Brother: On a Kansas Wheat Farm During K 978.1 Snyder, C. Hugh 2006 the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression Flint Hils Cowboys: Tales From the Tallgrass Praries K 978.1 Hoy, James 2007 John Brown to Bob Dole: Movers and Shakers in Kansas K 978.1 John Brown 2007 Not Afraid of Dogs JP Pitzer, Susanna 2007 Revolutionary heart: the life of Clarina Nichols and the 305.42 Eickhoff, Diane 2007 pioneering crusade for women's rights The Virgin of Small Plains F Pickard, Nancy 2007 Words of a Praries Alchemist K 811.54 Low, Denise 2007 The Boy Who Was Raised by Librarians JP Morris 2008 From Emporia: the story of William Allen White J 818.52 Buller, Beverley 2008 Hellfire Canyon F McCoy 2008 The Guide to Kansas Birds and Birding Hot Spots K 598.0978 Gress, Bob 2009 Kansas Opera Houses: Actors & Communioty Events 1855- K 792.5 Rhoads, Jane 2009 1925 The Blue Shoe: a tale of Thievery, Villainy, Sorcery, and JF Townley, Rod 2010 Shoes The Evolution of Shadows F Malott, Jason -

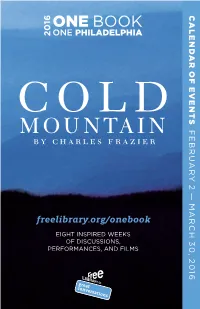

2016 Calendar of Events

CALENDAR OF EVENTS OF EVENTS CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2 — MARCH 30, 2016 2 — MARCH 30, FEBRUARY EIGHT INSPIRED WEEKS OF DISCUSSIONS, PERFORMANCES, AND FILMS 2016 FEATURED TITLES FEATURED 2016 WELCOME 2016 FEATURED TITLES pg 2 WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR pg 3 YOUTH COMPANION BOOKS pg 4 ADDITIONAL READING SUGGESTIONS pg 5 DISCUSSION GROUPS AND QUESTIONS pg 6-7 FILM SCREENINGS pg 8-9 GENERAL EVENTS pg 10 EVENTS FOR CHILDREN, TEENS, AND FAMILIES pg 21 COMMUNITY PARTNERS pg 27 SPONSORS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS pg 30 The centerpiece of 2016 One Book, One Philadelphia is author Charles Frazier’s historical novel Cold Mountain. Set at the end of the Civil War, Cold Mountain tells the heartrending story of Inman, a wounded Confederate soldier who walks away from the horrors of war to return home to his beloved, Ada. Cold Mountain BY CHARLES FRAZIER His perilous journey through the war-ravaged landscape of North Carolina Cold Mountain made publishing history when it topped the interweaves with Ada’s struggles to maintain her father’s farm as she awaits New York Times bestseller list for 61 weeks and sold 3 million Inman’s return. A compelling love story beats at the heart of Cold Mountain, copies. A richly detailed American epic, it is the story of a Civil propelling the action and keeping readers anxiously turning pages. War soldier journeying through a divided country to return Critics have praised Cold Mountain for its lyrical language, its reverential to the woman he loves, while she struggles to maintain her descriptions of the Southern landscape, and its powerful storytelling that dramatizes father’s farm and make sense of a new and troubling world. -

Indiebestsellers

Indie Bestsellers Week of 12.12.13 HardcoverFICTION NONFICTION 1. The Goldfinch 1. David and Goliath Donna Tartt, Little Brown, $30 Malcolm Gladwell, Little Brown, $29 2. Dog Songs 2. Things That Matter Mary Oliver, Penguin Press, $26.95 Charles Krauthammer, Crown Forum, $28 3. The Bully Pulpit 3. Sycamore Row Doris Kearns Goodwin, S&S, $40 John Grisham, Doubleday, $28.95 4. I Am Malala 4. The Valley of Amazement Malala Yousafzai, Little Brown, $26 Amy Tan, Ecco, $29.99 5. One Summer: America, 1927 5. Aimless Love Bill Bryson, Doubleday, $28.95 Billy Collins, Random House, $26 6. Stitches Anne Lamott, Riverhead, $17.95 6. The First Phone Call From Heaven Mitch Albom, Harper, $24.99 7. I Could Pee on This Francesco Marciuliano, Chronicle, $12.95 7. S. J.J. Abrams, Doug Dorst, Mulholland, $35 8. Killing Jesus Bill O’Reilly, Martin Dugard, Holt, $28 8. The Luminaries ★ 9. George Washington’s Secret Six: The Eleanor Catton, Little Brown, $27 Spy Ring That Saved the American ★ 9. The Gods of Guilt Revolution Michael Connelly, Little Brown, $28 Brian Kilmeade, Don Yaeger, Sentinel, $27.95 10. The Boys in the Boat 10. The Circle Daniel James Brown, Viking, $28.95 Dave Eggers, Knopf, $27.95 11. The Men Who United the States 11. The Good Lord Bird Simon Winchester, Harper, $29.99 James McBride, Riverhead, $27.95 12. My Promised Land 12. The Lowland Ari Shavit, Spiegel & Grau, $28 Jhumpa Lahiri, Knopf, $27.95 13. This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage Ann Patchett, Harper, $27.99 ★ 13. -

The Good Lord Bird: Traducción Al Español Y Dialectología

Miguel Sanz Jiménez THE GOOD LORD BIRD: TRADUCCIÓN AL ESPAÑOL Y DIALECTOLOGÍA Director: Dr. D. Jorge Braga Riera Máster Universitario en Traducción Literaria Instituto Universitario de Lenguas Modernas y Traductores Facultad de Filología Universidad Complutense MÁSTER EN TRADUCCIÓN LITERARIA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DECLARACIÓN PERSONAL DE BUENA PRÁCTICA ACADÉMICA D. Miguel Sanz Jiménez, con NIF 05339044P, estudiante del Máster en Traducción Literaria de la Universidad Complutense, curso 2014/2015 DECLARA QUE: El Trabajo Fin de Máster titulado «The Good Lord Bird: Traducción al español y dialectología», presentado para la obtención del título correspondiente, es resultado de su propio estudio e investigación, absolutamente personal e inédito y no contiene material extraído de fuentes (en versión impresa o electrónica) que no estén debidamente recogidas en la bibliografía final e identificadas de forma clara y rigurosa en el cuerpo del trabajo como fuentes externas. Asimismo, es plenamente consciente de que el hecho de no respetar estos extremos le haría incurrir en plagio y asume, por tanto, las consecuencias que de ello pudieran derivarse, en primer lugar el suspenso en su calificación. Para que así conste a los efectos oportunos, firma la presenta declaración. En Madrid, a 5 de junio de 2015 Fdo.: Miguel Sanz Jiménez *Esta declaración debe adjuntarse al Trabajo Fin de Máster en el momento de su entrega. Agradecimientos: Me gustaría dar las gracias, por su contribución a este trabajo de fin de máster, a mi familia, lectores de las sucesivas versiones de esta traducción; a mis compañeros de fatigas, por sus ánimos y buen humor; y a mi tutor, por su infinita paciencia y sabio consejo. -

The Good Lord Bird Discussion Led by Don Markley

FOPSL Book Club: February 19, 2021 Book: The Hare with Amber Eyes Author: Edmund de Waal Discussion leader: Pearl Moskowitz The Good Lord Bird Discussion Led by Don Markley Last month, Don Markley presented The Good Lord Bird by James McBride which won the National Book Award for fiction in 2013. An African American graduate of Oberlin College, McBride was already well-known for his first book, a best-selling memoir titled The Color of Water (1995). His 2002 novel Miracle at St. Anna based on the black 92nd Infantry Division of World War II was later adapted as a film by director Spike Lee. His most recent novel Deacon King Kong won the 2021 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. McBride is also an accomplished tenor saxophonist, composer and songwriter. The Good Lord Bird focuses on events leading up and including John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry on October 16, 1859. The book ends with John Brown waiting to be hung. The club discussion focused on the character of Onion, a young black boy who disguises himself as a girl. Through Onion’s eyes the reader examines the relationships between slaves and masters, free blacks and white abolitionists, black women and white men—the combinations are many and each tells a different part of antebellum life. Among the club comments: the John Brown’s Body song, a marching song popular in the Union during the Civil War, was sung in Austria! It turns out the song’s melody was later used for The Battle Hymn of the Republic (or Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory outside of the United States). -

1144 05/16 Issue One Thousand One Hundred Forty-Four Thursday, May Sixteen, Mmxix

#1144 05/16 issue one thousand one hundred forty-four thursday, may sixteen, mmxix “9-1-1: LONE STAR” Series / FOX TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX TELEVISION 10201 W. Pico Blvd, Bldg. 1, Los Angeles, CA 90064 [email protected] PHONE: 310-969-5511 FAX: 310-969-4886 STATUS: Summer 2019 PRODUCER: Ryan Murphy - Brad Falchuk - Tim Minear CAST: Rob Lowe RYAN MURPHY PRODUCTIONS 10201 W. Pico Blvd., Bldg. 12, The Loft, Los Angeles, CA 90035 310-369-3970 Follows a sophisticated New York cop (Lowe) who, along with his son, re-locates to Austin, and must try to balance saving those who are at their most vulnerable with solving the problems in his own life. “355” Feature Film 05-09-19 ê GENRE FILMS 10201 West Pico Boulevard Building 49, Los Angeles, CA 90035 PHONE: 310-369-2842 STATUS: July 8 LOCATION: Paris - London - Morocco PRODUCER: Kelly Carmichael WRITER: Theresa Rebeck DIRECTOR: Simon Kinberg LP: Richard Hewitt PM: Jennifer Wynne DP: Roger Deakins CAST: Jessica Chastain - Penelope Cruz - Lupita Nyong’o - Fan Bingbing - Sebastian Stan - Edgar Ramirez FRECKLE FILMS 205 West 57th St., New York, NY 10019 646-830-3365 [email protected] FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT 150 W. 22nd Street, Suite 1025, New York, NY 10011 917-484-8900 [email protected] GOLDEN TITLE 29 Austin Road, 11/F, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China UNIVERSAL PICTURES 100 Universal City Plaza Universal City, CA 91608 818-777-1000 A large-scale espionage film about international agents in a grounded, edgy action thriller. The film involves these top agents from organizations around the world uniting to stop a global organization from acquiring a weapon that could plunge an already unstable world into total chaos. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Press Release

300 SW 10th Ave. phone: 785-296-3296 Rm 312-N fax: 785-296-6650 Topeka, KS 66612-1593 www.kslib.info Joanne Budler, State Librarian Sam Brownback, Governor IMMEDIATE RELEASE: June 17, 2014 For more information, contact: Candace LeDuc, 785-291-3230 The State Library of Kansas Announces the 2014 Kansas Notable Books 15 books celebrating Kansas cultural heritage Topeka, KS, — The State Library of Kansas is pleased to announce 15 books featuring quality titles with wide public appeal, either written by Kansans or about a Kansas-related topic. The Kansas Notable Book List is the only honor for Kansas books by Kansans, highlighting our lively contemporary writing community and encouraging readers to enjoy some of the best writing of the authors among us. A committee of Kansas Center for the Book (KCFB) Affiliates, Fellows, librarians and authors of previous Notable Books identifies these titles from among those published the previous year, and the State Librarian makes the selection for the final List. An awards ceremony will be held at the Kansas Book Festival, September 13, 2014, to recognize the talented Notable Book authors. Throughout the award year, KCFB promotes all the titles on that year's List electronically, at literary events, and among librarians and booksellers. For more information about the Kansas Notable Book project, call 785-296-3296, visit www.kslib.info/notablebooks or email [email protected]. 2014 Kansas Notable Books Biting through the Skin: An Indian Kitchen in America’s Heartland by Nina Mukerjee Furstenau At once a traveler’s tale, a memoir, and a mouthwatering cookbook, Biting through the Skin offers a first- generation immigrant’s perspective on growing up in America’s heartland. -

Vanderlust Mary Hollendoner ’98 Embarks on the Ultimate Family Road Trip

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 Sometimes the best escape from the world is to drive right into it. VANDERLUST MARY HOLLENDONER ’98 EMBARKS ON THE ULTIMATE FAMILY ROAD TRIP FIVE DOLLARS Dartmouth FP Wedding Spring 2019 New font.qxp_Layout 1 3/12/19 3:40 PM Page 1 H W’ P B B NEW BOSTON ROAD Norwich, VT CLOVERTOP - Lyme, NH SOLD y h p a r g o t o h P e u h o n STARBUCK ROAD - Pomfret, VT PARADE GROUND ROAD - Hanover, NH o D y m A © The Perfect Setting for an Exquisite Wedding is Vermont’s Most Beautiful Address. The Woodstock Inn & Resort, one of New England’s most scenic, romantic, and luxurious destinations for a Vermont wedding, is ready to make your celebration perfect in every way. Our experienced staff will assist you with every detail — from room reservations to dinner menus, wedding cakes to rehearsal dinners. Personal Wedding Coordinator • Full Wedding Venue Services • Exquisite Wedding Cakes 5 T G, W, VT 802.457.2600 35 S M S, H, NH 603.643.0599 Customized Wedding Menus • Bridal Packages at The Spa • Year-round Recreational Activities • Exclusive Room Rates @ . . The World’s Best Hotels ~ Travel + Leisure Woodstock, Vermont | 802.457.6647 | www.woodstockinn.com S . P . BIG PICTURE Climate Change Dartmouth’s long and imperfect relationship with Native Americans took a turn June 25 when the weathervane atop Baker Library tower came down for good. President Phil Hanlon ’77 ordered the removal of the massive, 92-year-old copper vane following recent complaints about its offensive portrayal of a Native American. -

Nineteenth Century US

—The House Girl by Tara Conklin Pre-Civil War —Mrs. Poe by Lynn Cullen North America —West by Carys Davies —The Daring Ladies of Lowell by Kate Alcott —Washington Black by Esi Edugyan —Mad Boy by Nick Arvin 19th Century —A Stranger Here Below by Charles Fergus —Conjure Women by Afia Atakora (Gideon Stoltz Series #1) —Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood —The Eulogist by Terry Gamble North America —The Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb by —The Signature of all Things by Elizabeth Melanie Benjamin Gilbert —Sons of Blackbird Mountain by Joanne —Where the Lost Wander by Amy Harmon Bischof —A Friend of Mr. Lincoln by Stephen Harrigan —The Movement of Stars by Amy Brill —The Known World by Edward P. Jones —The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier —The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd —Mrs. Grant and Madame Jule by Jennifer —The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell by Chiaverini William Klaber —The Rathbones by Janice Clark —Song Yet Sung by James McBride —Finn by Jon Clinch —The Good Lord Bird by James McBride —The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates —The Mapmaker’s Children by Sarah McCoy Civil War Era —A Murder in Time by Julie McElwain (Kendra —Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks Donovan Series #1) —Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen by Sarah —The Poe Shadow by Matthew Pearl Bird Explore one of the defining centuries —The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie —March by Geraldine Brooks Newton by Jane Smiley of American history. the era of the —Fallen Land by Taylor Brown Civil War, The industrial Revolution, —Chang and Eng by Darin Strauss —White Doves at Morning by James Lee Burke Emancipation, and Reconstruction. -

The Good Lord Bird

— A U T H O R B I O — — R E A D A L I K E S — James McBride is an author, musician The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead and screenwriter. His landmark memoir, "The Color of Water," rested Chronicles the daring survival story of on the New York Times bestseller list a cotton plantation slave in Georgia, for two years. It is considered an who, after suffering at the hands of American classic and is read in schools both her owners and fellow slaves, and universities across the United races through the Underground States. His debut novel, "Miracle at Railroad with a relentless St. Anna" was translated into a major slave-catcher close behind. motion picture directed by American film icon Spike Lee. It was released by Disney/Touchstone in September 2008. James wrote the script for "Miracle At St. Anna and co-wrote Spike Lee's 2012 "Red Hook Summer." His novel, Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks "Song Yet Sung," was released in paperback in January Cloudsplitter is dazzling in its 2009. His latest novel "The Good Lord Bird," about re-creation of the political and social American revolutionary John Brown, is the winner of the landscape of our history during the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction. years before the Civil War, when slavery was tearing the country apart. James is also a former staff writer for The Boston Globe, But within this broader scope, Russell People Magazine and The Washington Post. His work has Banks has given us a riveting, appeared in Essence, Rolling Stone, and The New York suspenseful, heartbreaking narrative Times. -

UTZINGER-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (1.843Mb)

SCOTLAND READS AN AMERICAN BOOK: THE INTERNATIONAL CIRCULATION OF VIOLENCE, NATION, AND RACE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Dissertation by JEFFREY CHARLES UTZINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Ira Dworkin Committee Members, Larry J. Reynolds Angela P. Hudson Lawrence J. Oliver Susan B. Egenolf Head of Department, Maura Ives December 2019 Major Subject: English Copyright 2019 Jeffrey C. Utzinger ABSTRACT Travel abroad in the early nineteenth century, especially to the British Isles, not only shaped North American writers’ worldviews, it also provided many writers with the opportunity to procure additional publishers for their works which, in turn, disseminated these writers’ views across the British Isles. Much scholarship devoted to influences on nineteenth-century literature tends to conflate the British Isles into one coherent nation. This study, however, focuses on Scotland as a distinct region within the British Isles. The works of eighteenth-century Scottish economists, historians, mathematicians, and philosophers gave birth to what became known as the Scottish Enlightenment, a movement that shaped both the British Isles and North America. One of the most influential ideas to emerge from the Scottish Enlightenment was stadial theory, the idea that humans come to being in a rudimentary or savage state and progress over time into civilized people who engage in economies of trade. Stadial theory informed nineteenth-century political and economic policies, which attempted to justify both the enslavement of people of color and the sustained campaigns of removing indigenous people from lands in North America.