Obsidian SPR15 Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Titles Highlighted in Yellow Were Purchased in 2018

Titles highlighted in yellow were purchased in 2018 Title Location/Author Year Airball: My Life in Shorts YA Harkrader 2006 Capote in Kansas: a drawn novel F Parks, Ande 2006 Deputy Harvey and the Ant Cow Caper JP Sneed, Brad 2006 John Brown, abolitionist: the man 973.7 Reynolds, David 2006 The Kansas Guidebook for Explorers 917.81 Penner, Marci 2006 The Moon Butter Route CS Yoho, Max 2006 Oceans of Kansas: a natural history of the western interior 560.457 Everhart, Michael 2006 sea Wildflowers and Grasses of Kansas: A Field Guide 582.13 Haddock, Michael 2006 The Youngest Brother: On a Kansas Wheat Farm During K 978.1 Snyder, C. Hugh 2006 the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression Flint Hils Cowboys: Tales From the Tallgrass Praries K 978.1 Hoy, James 2007 John Brown to Bob Dole: Movers and Shakers in Kansas K 978.1 John Brown 2007 Not Afraid of Dogs JP Pitzer, Susanna 2007 Revolutionary heart: the life of Clarina Nichols and the 305.42 Eickhoff, Diane 2007 pioneering crusade for women's rights The Virgin of Small Plains F Pickard, Nancy 2007 Words of a Praries Alchemist K 811.54 Low, Denise 2007 The Boy Who Was Raised by Librarians JP Morris 2008 From Emporia: the story of William Allen White J 818.52 Buller, Beverley 2008 Hellfire Canyon F McCoy 2008 The Guide to Kansas Birds and Birding Hot Spots K 598.0978 Gress, Bob 2009 Kansas Opera Houses: Actors & Communioty Events 1855- K 792.5 Rhoads, Jane 2009 1925 The Blue Shoe: a tale of Thievery, Villainy, Sorcery, and JF Townley, Rod 2010 Shoes The Evolution of Shadows F Malott, Jason -

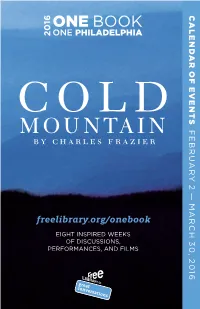

2016 Calendar of Events

CALENDAR OF EVENTS OF EVENTS CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2 — MARCH 30, 2016 2 — MARCH 30, FEBRUARY EIGHT INSPIRED WEEKS OF DISCUSSIONS, PERFORMANCES, AND FILMS 2016 FEATURED TITLES FEATURED 2016 WELCOME 2016 FEATURED TITLES pg 2 WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR pg 3 YOUTH COMPANION BOOKS pg 4 ADDITIONAL READING SUGGESTIONS pg 5 DISCUSSION GROUPS AND QUESTIONS pg 6-7 FILM SCREENINGS pg 8-9 GENERAL EVENTS pg 10 EVENTS FOR CHILDREN, TEENS, AND FAMILIES pg 21 COMMUNITY PARTNERS pg 27 SPONSORS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS pg 30 The centerpiece of 2016 One Book, One Philadelphia is author Charles Frazier’s historical novel Cold Mountain. Set at the end of the Civil War, Cold Mountain tells the heartrending story of Inman, a wounded Confederate soldier who walks away from the horrors of war to return home to his beloved, Ada. Cold Mountain BY CHARLES FRAZIER His perilous journey through the war-ravaged landscape of North Carolina Cold Mountain made publishing history when it topped the interweaves with Ada’s struggles to maintain her father’s farm as she awaits New York Times bestseller list for 61 weeks and sold 3 million Inman’s return. A compelling love story beats at the heart of Cold Mountain, copies. A richly detailed American epic, it is the story of a Civil propelling the action and keeping readers anxiously turning pages. War soldier journeying through a divided country to return Critics have praised Cold Mountain for its lyrical language, its reverential to the woman he loves, while she struggles to maintain her descriptions of the Southern landscape, and its powerful storytelling that dramatizes father’s farm and make sense of a new and troubling world. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

Puzzling the Intervals: Blind Tom and the Poetics of The

“Puzzling the Intervals” Oxford Handbooks Online “Puzzling the Intervals”: Blind Tom and the Poetics of the Sonic Slave Narrative Daphne A. Brooks The Oxford Handbook of the African American Slave Narrative Edited by John Ernest Print Publication Date: Apr 2014 Subject: Literature, American Literature Online Publication Date: May DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199731480.013.023 2014 Abstract and Keywords This article explores the enslaved musician Blind Tom’s sonic repertoire as an alternative to that of the discursive slave narrative, and it considers the methodological challenges of theorizing the conditions of captivity and freedom in cultural representations of Blind Tom’s performances. The article explores how the extant anecdotes, testimonials and cultural ephemera about Thomas Wiggins live in tension with the conventional fugitive’s narrative, and it traces the ways in which the “scenarios” emerging from the Blind Tom archive reveal a consistent set of themes concerning aesthetic authorship, imitation, reproduction and duplication, which tell us much about quotidian forms of power and subjugation in the cultural life of slavery, as well as the cultural means by which a figure like Blind Tom complicated and disrupted that power. Keywords: sound, listening, sonic ekphrasis, echo, memory, reproduction, imitation, transcription, notation, improvisation For my master, whose restless, craving, vicious nature roved about day and night, seeking whom to devour, had just left me with stinging, scorching words, words that scathed ear and brain life fire! —Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do. -

Crisis on Infinite Earths Free

FREE CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS PDF DC Comics | 368 pages | 25 May 2007 | D C Comics (a division of Warner Brothers - A Time Warner Entertainment Co.) | 9781563897504 | English | New York, United States How to Watch 'Crisis on Infinite Earths' Crossover Event on Netflix - What's on Netflix At the beginning of time, the Big Bang occurred, forming the universe. However, where there should have been one universe, there were many, each one a replication of the first, with their own separate histories. The Crisis on Infinite Earths was a Multiversal catastrophe that resulted in the destruction of countless parallel universes, and Crisis on Infinite Earths recreation of a single positive matter universe and an antimatter universe at the dawn of time. At the present time, a great white wall of pure antimatter energy stretches out across the cosmos. It pervades the Multiverse, consuming entire galaxies. On an unknown Crisis on Infinite Earths world, a being named Pariah arrives. He Crisis on Infinite Earths forced to witness the death of multiple worlds in multiple dimensions. He disappears as he is transported to the parallel world known as Earth-Three. On that world, the Crime Syndicate, in a rare demonstration of heroism, strives to save their beleaguered planet. However, even their combined might cannot prevent their deaths at the antimatter wall. The planet's sole hero, Alexander Luthor, retreats to his home where his wife, Lois, holds their infant son, Alexander Jr. Luthor places his son into an experimental rocket capsule and launches him from the planet Earth. As Earth-Three dies, Alexander's capsule pierces the vibrational wall separating dimensions. -

Bid Winners.Xlsx

Division Gym Name Team Name Type of Bid Mini Level 1 Extreme Allstars KY Blue Diamonds Paid Mini Level 1 Champion Cheer Starlight Paid Mini Level 1 Empire Cheerleading Lavish Paid Mini Level 1 Empire Cheerleading Lavish At Large Mini Level 1 Powersports Cheer Solar Mini At Large Mini Level 1 Louisiana Cheer Force Baby Blue At Large Mini Level 1 TexStar Athletics Static At Large Mini Level 1 Cheerville Hendersonville Ursula At Large Mini Level 1 Rival Athletics Mini Marvels At Large Mini Level 1 NEO Allstars Blush At Large Mini Level 1 Tiger Cheer Athletics Betas At Large Mini Level 1 Cats Cheerleading Sparkle Kitties At Large Mini Level 1 Spirit Authority Midnight At Large Mini Level 1 Cheeriffic Allstars Boss Ladies At Large Mini Level 1 Tribe Chieftains At Large Mini Level 1 Cheer FX Mini Blizzards At Large Mini Level 1 Legend Allstar Falcon At Large Mini Level 1 Tiger Cheer Athletics Betas At Large Mini Level 1 Zero Gravity Athletics Cosmos At Large Mini Level 1 Empire Cheerleading Lavish At Large Mini Level 1 Allstar Cheer Express Dynamites At Large Mini Level 1 Champion Cheer Sparklers At Large Mini Level 1 Arkansas Cheer Academy Commanders At Large Mini Level 1 Cheer Central Suns Starlites At Large Mini Level 1 Cheerville Catwoman At Large Mini Level 1 East Celebrity Elite Cherry Bombs At Large Mini Level 1 Rockstar Cheer Arizona Little Mix At Large Mini Level 1 Spirit Xtreme Mighty At Large Mini Level 1 Steel Elite Athletics Royal Rubies At Large Mini Level 1 Gem Revolution Mini Jewels At Large Mini Level 1 CFA Angels At Large Mini -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

Let Us Give Them Something to Play With”: the Preservation of the Hermitage by the Ladies’ Hermitage Association

“LET US GIVE THEM SOMETHING TO PLAY WITH”: THE PRESERVATION OF THE HERMITAGE BY THE LADIES’ HERMITAGE ASSOCIATION by Danielle M. Ullrich A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Middle Tennessee State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History with an Emphasis in Public History Murfreesboro, TN May 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle, Chair Dr. Rebecca Conard ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My parents, Dennis and Michelle Ullrich, instilled in me a respect for history at an early age and it is because of them that I am here today, writing about what I love. However, I would also not have made it through without the prayers and support of my brother, Ron, and my grandmother, Carol, who have reminded me even though I grow tired and weary, those who hope in the Lord will find new strength. Besides my family, I want to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle and Dr. Rebecca Conard. Dr. Hoffschwelle, your wealth of knowledge on Tennessee history and your editing expertise has been a great help completing my thesis. Also, Dr. Conard, your support throughout my academic career at MTSU has helped guide me towards a career in Public History. Special thanks to Marsha Mullin of Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, for reading a draft of my thesis and giving me feedback. And last, but certainly not least, to all the Hermitage interpreters who encouraged me with their questions and with their curiosity. ii ABSTRACT Since 1889, Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage has been open to the public as a museum thanks to the work of the Ladies’ Hermitage Association. -

229 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05246-8 - The Cambridge Companion to: American Science Fiction Edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan Index More information INDEX Aarseth, Espen, 139 agency panic, 49 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (fi lm, Agents of SHIELD (television, 2013–), 55 1948), 113 Alas, Babylon (Frank, 1959), 184 Abbott, Carl, 173 Aldiss, Brian, 32 Abrams, J.J., 48 , 119 Alexie, Sherman, 55 Abyss, The (fi lm, Cameron 1989), 113 Alias (television, 2001–06, 48 Acker, Kathy, 103 Alien (fi lm, Scott 1979), 116 , 175 , 198 Ackerman, Forrest J., 21 alien encounters Adam Strange (comic book), 131 abduction by aliens, 36 Adams, Neal, 132 , 133 Afrofuturism and, 60 Adventures of Superman, The (radio alien abduction narratives, 184 broadcast, 1946), 130 alien invasion narratives, 45–50 , 115 , 184 African American science fi ction. assimilation of human bodies, 115 , 184 See also Afrofuturism ; race assimilation/estrangement dialectic African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 and, 176 black agency in Hollywood SF, 116 global consciousness and, 1 black genius fi gure in, 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , indigenous futurism and, 177 65 , 67 internal “Aliens R US” motif, 119 blackness as allegorical SF subtext, 120 natural disasters and, 47 blaxploitation fi lms, 117 post-9/11 reformulation of, 45 1970s revolutionary themes, 118 reverse colonization narratives, 45 , 174 nineteenth century SF and, 60 in space operas, 23 sexuality and, 60 Superman as alien, 128 , 129 Afrofuturism. See also African American sympathetic treatment of aliens, 38 , 39 , science fi ction ; race 50 , 60 overview, 58 War of the Worlds and, 1 , 3 , 143 , 172 , 174 African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 wars with alien races, 3 , 7 , 23 , 39 , 40 Afrodiasporic magic in, 65 Alien Nation (fi lm, Baker 1988), 119 black racial superiority in, 61 Alien Nation (television, 1989–1990), 120 future race war theme, 62 , 64 , 89 , 95n17 Alien Trespass (fi lm, 2009), 46 near-future focus in, 61 Alien vs.