Annotated Excerpts from Successful Proposals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Manchild in the Promised Land

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „African American Ghettos Portrayed in Autobiography: The Long Steady March from Lincoln to Obama 1865-2009” Verfasserin Mag. Dawn Kremslehner-Haas angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz To my dear husband Hermann, without whose loving support this study would have never been completed. Thematic Overview BLACK URBAN GHETTOS PORTRAYED IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY: THE LONG STEADY MARCH FROM LINCOLN TO OBAMA 1865-2009 I. SETTING THE STAGE: PRE-1965 IDEOLOGICAL VANTAGE POINT: ARGUMENT: AUTHOR: WORK: 1 Conservative Behaviorist Cultural Argument: Family Structure Harriet Jacobs Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl 2 Liberal Structuralist Racial Argument: Historic Racism Malcolm X / Haley The Autobiography of Malcolm X 3 Liberal Structuralist Economic Argument: Great Migration Claude Brown Manchild in the Promised Land II. LOCKED INTO A SPIRAL OF DECLINE: POST-1965 IDEOLOGICAL VANTAGE POINT: ARGUMENT: AUTHOR: WORK: 4 Conservative Behaviorist Cultural Argument: Cultural Revolution Cupcake Brown A Piece of Cake 5 Liberal Structuralist Racial Argument: Residential Segregation Nathan McCall Makes Me Wanna Holler 6 Liberal Structuralist Economic Argument: Urban Restructuring John E. Wideman Brothers and Keepers I Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 1. General Introduction 1 2. African American Autobiography in the Context of Cultural Studies 7 2.1. The Historical Significance of African American Biography 7 2.2. African American Autobiography as an Interdisciplinary Subject 9 2.3. -

Artist 5Th Dimension, the 5Th Dimension, the a Flock of Seagulls

Artist 5th Dimension, The 5th Dimension, The A Flock of Seagulls AC/DC Ackerman, William Adam and the Ants Adam Ant Adam Ant Adam Ant Adams, Bryan Adams, Bryan Adams, Ryan & the Cardinals Aerosmith Aerosmith Alice in Chains Allman, Duane Amazing Rhythm Aces America America April Wine Arcadia Archies, The Asia Asleep at the Wheel Association, The Association, The Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Autry, Gene Axe Axton, Hoyt Axton, Hoyt !1 Bachman Turner Overdrive Bad Company Bad Company Bad Company Bad English Badlands Badlands Band, The Bare, Bobby Bay City Rollers Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beaverteeth Bennett, Tony Benson, George Bent Left Big Audio Dynamite II Billy Squier Bishop, Elvin Bishop, Elvin Bishop, Stephen Black N Blue Black Sabbath Blind Faith Bloodrock Bloodrock Bloodrock Bloodstone Blue Nile, The Blue Oyster Cult !2 Blue Ridge Rangers Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Blues Pills Blues Pills Bob Marley and the Wailers Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys BoDeans Bonham Bonoff, Karla Boston Boston Boston Boston Symphony Orchestra Bowie, David Braddock, Bobby Brickell, Edie & New Bohemians Briley, Martin Britny Fox Brown, Clarence Gatemouth Brown, Toni & Garthwaite, Terry Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Bruce -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

Catalogue (Pdf)

presents November 3-11, 2017 WHERE THE MIND REELS rendezvouswithmadness.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS FESTIVAL CALENDAR 2 BOX OFFICE AND SPONSORS 4 ABOUT WORKMAN ARTS 6 FESTIVAL LETTERS 8 FILM PROGRAMS 17 MEDIA ART INSTALLATION: DE-INSTITUTE 18 SPECIAL EVENT: DE PROFUNDIS 42 SHORTS SCREENING WITH FEATURES 44 BECOME A FRIEND OF THE FESTIVAL 48 MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES 53 RENDEZVOUS POSTERS (1993-2016) 54 INDEX 56 Cover Artwork: Claudette Abrams FESTIVAL CALENDAR FESTIVAL CALENDAR FRIDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY NOVEMBER 3 NOVEMBER 5 NOVEMBER 6 NOVEMBER 7 NOVEMBER 8 NOVEMBER 9 NOVEMBER 10 NOVEMBER 11 5 PM 11 AM - 6 PM OPENING DE-INSTITUTE: DE-INSTITUTE: MEDIA ART MEDIA ART INSTALLATION INSTALLATION Workman Theatre, Lower Hall Workman Theatre, Lower Hall 5 - 6:30 PM OPENING NIGHT GALA RECEPTION Workman Theatre 7 PM MAD TO BE NORMAL (Feature) Robert Mullan St. Anne’s Church SATURDAY NOVEMBER 4 11 AM 11 AM page 25 12 noon - PWYC / accessible 12 noon - PWYC / accessible MAD TO BE NORMAL FRONTIERS: DOCUMENTARY AND DR. FEELGOOD (FEATURE) PUSHBACK (FEATURE) (Feature) ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT Eve Marson Matthew Hayes Robert Mullan Marta Espar & Marc Parramon CAMH Russell Street, Room 2029 CAMH Queen Street, Training A/B Workman Theatre SCREENING WITH: BROWNDALE (Short) / Thomas Norton MISTISSINI HEALING (Short) / Stephanie Vizi Workman Theatre 2 PM page 20 2 PM page 26 I AM ANOTHER YOU (Feature) WOMEN ON THE VERGE Nanfu Wang (Shorts Program) SCREENING WITH: Workman Theatre AN OTHER (Short) / Marie-Michéle Genest Workman Theatre -

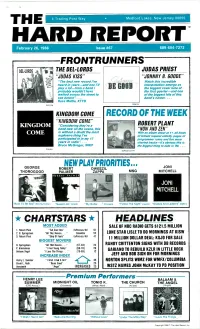

Frontrunners Headlines

THE 4 Trading Post Way Medford Lakes. New Jersey 08055 HARD REPORT February 26, 1988 Issue #67 609-654-7272 alb FRONTRUNNERS THE DEL -LORDS JUDAS PRIEST "JUDAS KISS" "JOHNNY B. GOODE" "The best new record I've Watch this incredible heard in years-and one interpretation emerge as play a lot-from a band / the biggest cover tune of probably wouldn't have the first quarter-and one walked across the street to of the biggest hits of this see before".. band's career. ... Russ Mottla, KTYD Atlantic Enigma KINGDOM COME RECORD OF THE WEEK "KINGDOM COME" ROBERT PLANT KINGDOM "Considering they're a band new on the scene, this "NOW AND ZEN" COME is without a doubt the most With an a/bum debut at 1*, all kinds explosive thing I've of instant request activity, pages of participated in in my 17 programmer raves and five more years in radio". ... ofiej4v.charted tracks-it's obvious this is Bruce McGregor, WRIF the biggest thing to date in '88.... Polydor E s Pa r a nz a / At I NEW PLAY PRIORITIES... JONI GEORGE ROBERT DWEEZIL THOROGOOD PALMER ZAPPA MSG MITCHELL ERT PALMER MOOG JONI MITCHELL "Born To Be Bad" (EMI/Manhattan) "Sweet Lies" (Island) ' My Guitar (Chrysalis) 'Follow The Night" (capitol)"Snakes And Ladders" (Geffen) CHARTSTARS HEADLINES MOST ADDED SALE OF NBC RADIO GETS $121.5 MILLION 1. Robert Plant "Tall Cool One" EsParanza/Atl 91 LONE STAR LISLE TO DO MORNINGS AT KISW 2. B. Springsteen "All That Heaven . ." Columbia 52 3. Robert Plant "Ship Of Fools" EsParanza/Atl 47 11 MILLION DOLLAR DEAL: KSJO FOR SALE BIGGEST MOVERS RANDY CRITTENTON SIGNS WITH DB RECORDS B. -

Carter, Reagan Win New Hampshire Primaries Reagan Tops Kennedy Bush by Claims Moral 3-1 Margin Victory

mo c.J Student trustee candidates profiled First of two parts, p. 3 Connecticut Satin, (Eamnna Serving Storrs Since 1896 Vol. XXXIII, No. 88 STORRS, CONNECTICUT Wednesday, February 27,1980 Carter, Reagan win New Hampshire primaries Reagan tops Kennedy Bush by claims moral 3-1 margin victory By JIM CONDON By MARY MESSINA MANCHESTER. N.H.— MANCHESTER. N.H.— Sen. Edward Kennedy Republican candidate for claimed victory in the New president Gov. Ronald Hampshire primary, Reagan defeated rival although he captured only 38 George Bush here last night percent of the vote while by a surprising margin of President Carter won 49 per- almost 3-1. cent. With almost 85 percent of the votes in late last night. Speaking at his Man- Reagan was leading Bush by chester headquarters after more than 30.000 votes. most of the returns were in. In an earlier unexpected Kennedy said. "We got move. Reagan fired three of about 40 percent. Four years his top campaign workers, ago Jimniy Carter got 28 citing the need for a sharp percent and claimed victory. Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter (UPI). reduction in campaign ex- We're claiming victory penses. tonight." Reagan announced that Florida nuclear plant flooded; Kennedy told the crowd of William J. Casey, the new supporters that he has no in- executive vice-chairman and tention of dropping from the campaign director. will poses no immediate threat presidential race. "Wc con- replace John Sears, who will tinue this campaign. Wc return to private practice as CRYSTAL RIVER, Fla.(UPI)—As much as public in the area of the plant nor with any 60,000 gallons of radioactive water gushed out radiation release to the public." continue in Massachusetts, a lawyer. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The -

Protesters Rally to Revive the NHS

#12 | theoccupiedtimes.com | @OccupiedTimes 21MAR2012 BLOCK THE BILL PROTESTERS RALLY TO REVIVE THE NHS NHS staff were joined last Saturday As the crowd advanced police by members of the public and activists officers made repeated attempts to including contingents from Occupy prevent the procession, succeeding only London and Anonymous UK in a in separating protesters, but failing to demonstration over the government’s stop them. Eventually, after turning onto proposed health service reforms. Chancery Lane, the last few protesters Around 200 people gathered outside still advancing were kettled by police the Department of Health building in using force. One man was tripped from Whitehall, where speakers addressed behind while running and another had his the crowd. head smashed into a window. As the crowd grew, only a minimal Officers initially informed the kettled police presence could be seen as demonstrators they would either be people discussed the impending Health arrested under a Section 12 order or and Social Care bill in a subdued could give their personal details and atmosphere. A small group then moved be escorted out - but several activists into the road and sat down with arms demanded clarification as to whether linked, blocking traffic and prompting these were the only two options open more protesters to join in solidarity. to them. Police eventually escorted Within minutes the majority of people them out one-by-one, without who had gathered for the demo - taking information, but past Forward including elderly and disabled people, Intelligence Officers filming the incident. as well as parents with small children Despite the historical importance of - were obstructing the road, chanting the government’s unmandated reforms, defiantly as surgical hats, masks and the small but spirited public defiance gloves were passed around. -

Rock Candy Magazine

MOSCOW MUSIC PEACE FESTIVAL STRICTLY OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION EXCUSE OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION STRICTLY FESTIVAL MUSIC PEACE MOSCOW COLLECTORS REMASTERED ISSUE EDITIONS & RELOADED 2 OUT NOW June–July 2017 £9.99 HARD, SWEET & STICKY LILLIAN AXE - ‘S/T’ LILLIAN AXE - ‘LOVE+WAR’ WARRANT - ‘CHERRY PIE’ WARRANT - ‘DIRTY ROTTEN FILTHY MOTHER’S FINEST - ‘IRON AGE’ STINKING RICH’ ROCK CANDY MAG ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY 2017 ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY MAG CANDY ROCK MAHOGANY RUSH - ‘LIVE’ FRANK MARINO - ‘WHAT’S NEXT’ FRANK MARINO FRANK MARINO - ‘JUGGERNAUT’ CREED - ‘S/T’ SURVIVOR ‘THE POWER OF ROCK AND ROLL’ ‘EYE OF THE TIGER’ KING KOBRA - ‘READY TO STRIKE’ KING KOBRA 707 - ‘S/T’ 707 - ‘THE SECOND ALBUM’ 707 - ‘MEGAFORCE’ OUTLAWS - ‘PLAYIN’ TO WIN’ ‘THRILL OF A LIFETIME’ “IT WAS LOUD – LIKE A FACTORY!” LOUD “IT WAS SAMMY HAGAR SALTY DOG TYKETTO - ‘DON’T COME EASY’ KICK AXE - ‘VICES’ KICK AXE KICK AXE - ‘ROCK THE WORLD’ ‘ALL NIGHT LONG’ ‘EVERY DOG HAS IT’S DAY’ ‘WELCOME TO THE CLUB’ NYMPHS -’S/T’ RTZ - ‘RETURN TO ZERO’ WARTHCHILD AMERICA GIRL - ‘SHEER GREED’ GIRL - ‘WASTED YOUTH’ LOVE/HATE ‘CLIMBIN’ THE WALLS’ ‘BLACKOUT IN THE RED ROOM’ MAIDEN ‘84 BEHIND THE SCENES ON THE LEGENDARY POLAND TOUR TARGET - ‘S/T’ TARGET - ‘CAPTURED’ MAYDAY - ‘S/T’ MAYDAY - ‘REVENGE’ BAD BOY - ‘THE BAND THAT BAD BOY - ‘BACK TO BACK’ MILWAUKEE MADE FAMOUS’ COMING SOON BAD ENGLISH - ‘S/T’ JETBOY - ‘FEEL THE SHAKE’ DOKKEN STONE FURY ALANNAH MILES - ‘S/T’ ‘BEAST FROM THE EAST’ ‘BURNS LIKE A STAR’ www.rockcandyrecords.com / [email protected] -

Contemporary Reading List by Author.Rtf

Contemporary Reading List By Author 20th - 21st Century ***= Young Adult Author TITLE Call # Pages AR Level Description Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart FIC ACH 181 Okonkwo, a proud village leader, is driven to murder and suicide by European changes to his traditional Ibo society. Adams, Douglas So Long and Thanks for the Fish FIC ADA 214 6.9 The quest continues... Against all odds, at the eleventh hour, and in the unlikeliest of places of all, Arthur Dent finds the girl of his dreams. Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything FIC ADA 232 No less a mission than preventing the destruction of the universe hurtles Arthur Dent and company through their third uproarious romp in space and time. Adams, Douglas Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy FIC ADA 309 After Earth is demolished to make way for a new hyperspatial expressway, Arthur Dent begins to hitch-hike through space. This insanely funny, satiric bestseller is about the end of the world and the days that follow it. Alexie, Sherman Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, The FIC ALE 229 Budding cartoonist Junior leaves his troubled school on the Spokane Indian Reservation to attend an all-white farm town school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. Alexie, Sherman Toughest Indian in the World FIC ALE 238 This "compulsively readable" short-story collection by best-selling author Alexie introduces the kind of American Indians who pay their bills, hold down jobs, and fall in and out of love. Alexie, Sherman Reservation Blues FIC ALE 306 4.6 The life of Spokane Indian Thomas Builds-the-Fire irrevocably changes when blues legend Robert Johnson miraculously appears on his reservation and passes the misfit storyteller his enchanted guitar.