Fauna of Australia. Volume 2B, Aves’ (Not Published)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Migration of Swallows in South Australia. by A

116 MOl?llA.N-Thc Migrat'ion 'of Swallows in S.A.. The Migration of Swallows in South Australia. By A. ,M. MORGAN, M.B., Ch.B. Four swallows inhabit South Australia. They are the Welcome-Swallow (Hirundo neoaJena), the Tree Swallow (Hylo c7wlidon nigricans caleyi), the Fairy Martin '01' Bottle Swallow (Lagenoplastes ariel), and the White-breasted Swallow (Ohera· mreca lC1tcosternon stonei). None is rconflned to South Aus tralia; 'the first theeebave been recorded from every part of the Australian Commonwealth, the fourth from every State except Tasmania, which it does not visit. Authorities differ considerably in their opinions as to the migratory habits of these birds on the Australian Continent. As regards 'I'asmania, all 'are agreed that they are purely migratory, leaving in: the winter, and returning next summer to nest. The flairy mrurtin is' probably only an occasional visitor, since Littler (Birds of Tas~ania) has not seen it. Gould (Handbook of the Birds 'of Australia) says of the welcome swallows-v'Dbe arrival of this bird in the southern portions of Australia is hailed as a welcome indication of the approach of .spring, and .is associated with precisely the same ideas as those popularly entertained respecting our own pretty swallow 'in Europe. The two species are, in fact, beautiful representatives of each other, and, assimilate ... in their migratory movements." Quoting Caley, he says further, "the earliest perjod of the year that I noticed the 'appearance of swallows. was July 12th, 1803, when 1 saw two . The latest period I 'observed them was 30th Ma~, 1806, when It number of them were flying high in the air." Gould also says, " ,u. -

Tree Swallows (Tachycineta Bicolor) Nesting on Wetlands Impacted by Oil Sands Mining Are Highly Parasitized by the Bird Blow Fly Protocalliphora Spp

Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 43(2), 2007, pp. 167–178 # Wildlife Disease Association 2007 TREE SWALLOWS (TACHYCINETA BICOLOR) NESTING ON WETLANDS IMPACTED BY OIL SANDS MINING ARE HIGHLY PARASITIZED BY THE BIRD BLOW FLY PROTOCALLIPHORA SPP. Marie-Line Gentes,1 Terry L. Whitworth,2 Cheryl Waldner,3 Heather Fenton,1 and Judit E. Smits1,4 1 Department of Veterinary Pathology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B4, Canada 2 Whitworth Pest Solutions, Inc., 2533 Inter Avenue, Puyallup, Washington, USA 3 Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B4, Canada 4 Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: Oil sands mining is steadily expanding in Alberta, Canada. Major companies are planning reclamation strategies for mine tailings, in which wetlands will be used for the bioremediation of water and sediments contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and naphthenic acids during the extraction process. A series of experimental wetlands were built on companies’ leases to assess the feasibility of this approach, and tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) were designated as upper trophic biological sentinels. From May to July 2004, prevalence and intensity of infestation with bird blow flies Protocalliphora spp. (Diptera: Calliphoridae) were measured in nests on oil sands reclaimed wetlands and compared with those on a reference site. Nestling growth and survival also were monitored. Prevalence of infestation was surprisingly high for a small cavity nester; 100% of the 38 nests examined were infested. Nests on wetlands containing oil sands waste materials harbored on average from 60% to 72% more blow fly larvae than those on the reference site. -

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

Aves: Hirundinidae)

1 2 Received Date : 19-Jun-2016 3 Revised Date : 14-Oct-2016 4 Accepted Date : 19-Oct-2016 5 Article type : Original Research 6 7 8 Convergent evolution in social swallows (Aves: Hirundinidae) 9 Running Title: Social swallows are morphologically convergent 10 Authors: Allison E. Johnson1*, Jonathan S. Mitchell2, Mary Bomberger Brown3 11 Affiliations: 12 1Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago 13 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan 14 3 School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska 15 Contact: 16 Allison E. Johnson*, Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 1101 E 57th Street, 17 Chicago, IL 60637, phone: 773-702-3070, email: [email protected] 18 Jonathan S. Mitchell, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, 19 Ruthven Museums Building, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, email: [email protected] 20 Mary Bomberger Brown, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Hardin Hall, 3310 21 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, NE 68583, phone: 402-472-8878, email: [email protected] 22 23 *Corresponding author. 24 Data archiving: Social and morphological data and R code utilized for data analysis have been 25 submitted as supplementary material associated with this manuscript. 26 27 Abstract: BehavioralAuthor Manuscript shifts can initiate morphological evolution by pushing lineages into new adaptive 28 zones. This has primarily been examined in ecological behaviors, such as foraging, but social behaviors 29 may also alter morphology. Swallows and martins (Hirundinidae) are aerial insectivores that exhibit a This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

Birds Along Lehi's Trail

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 15 Number 2 Article 10 7-31-2006 Birds Along Lehi's Trail Stephen L. Carr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carr, Stephen L. (2006) "Birds Along Lehi's Trail," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 15 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol15/iss2/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Birds Along Lehi’s Trail Author(s) Stephen L. Carr Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15/2 (2006): 84–93, 125–26. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract When Carr traveled to the Middle East, he observed the local birds. In this article, he suggests the possi- bility that the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi and his family relied on birds for food and for locating water. Carr discusses the various birds that Lehi’s family may have seen on their journey and the Mosaic law per- taining to those birds. Birds - ALOnG LEHI’S TRAIL stephen l. cARR 84 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 2, 2006 PHOTOGRAPHy By RICHARD wELLINGTOn he opportunity to observe The King James translators apparently ex- birds of the Middle East came to perienced difficulty in knowing exactly which me in September 2000 as a member Middle Eastern birds were meant in certain pas- Tof a small group of Latter-day Saints1 traveling in sages of the Hebrew Bible. -

The Evolution of Nest Construction in Swallows (Hirundinidae) Is Associated with the Decrease of Clutch Size

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 38/1 711-716 21.7.2006 The evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is associated with the decrease of clutch size P. HENEBERG A b s t r a c t : Variability of the nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is more diverse than in other families of oscine birds. I compared the nest-building behaviour with pooled data of clutch size and overall hatching success for 20 species of swallows. The clutch size was significantly higher in temperate cavity-adopting swallow species than in species using other nesting modes including species breeding in evolutionarily advanced mud nests (P<0.05) except of the burrow-excavating Bank Swallow. Decrease of the clutch size during the evolution of nest construction is not compensated by the increase of the overall hatching success. K e y w o r d s : Hirundinidae, nest construction, clutch size, evolution Birds use distinct methods to avoid nest-predation: active nest defence, nest camouflage and concealment or sheltered nesting. While large and powerful species prefer active nest-defence, swallows and martins usually prefer construction of sheltered nests (LLOYD 2004). The nests of swallows vary from natural cavities in trees and rocks, to self-exca- vated burrows to mud retorts and cups attached to vertical faces. Much attention has been devoted to the importance of controlling for phylogeny in com- parative tests (HARVEY & PAGEL 1991), including molecular phylogenetic studies of swallows (WINKLER & SHELDON 1993). Interactions between the nest-construction va- riability and the clutch size, however, had been ignored. -

Head-Scratching Method in Swallows Depends on Behavioral Context

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 679 shoulder-spot display during their observations of behavior in partridges. In all cases that I observed, the shoulder spot appeared to be a fear or flight intention display as described by Lumsden (1970). However, the display seemed secondary in importance compared to vocalizations and “tail flicking” during periods of extreme alarm. Examination of the shoul- der spot of a partridge confirmed the realignment of white underwing coverts to the top of the wing in the patagial region. The manipulation by the bird of underwing feathers appeared to be identical to that of Ruffed Grouse (Bonusa umbellus)(Garbutt 198 1). Since “display” implies actual communication between individuals further investigation is needed to de- termine if, in fact, the shoulder spot actually is serving a communication function in Gray Partridge. The shoulder spot in Gray Partridges and the display seen in grouse are morphologically similar. Lumsden (1970) concluded that the widespread occurrence of this display among grouse indicated it appeared relatively early in evolution. The morphological and behavioral similarities between the display in grouse and partridges suggest that the shoulder spot may have evolved even earlier. Since this is an escape behavior, and since many species of partridges and pheasants are difficult to observe in the wild, it may have been overlooked. Acknowledgments.-Theseobservations were made while the author was supported by funds from the North Dakota Game and Fish Department through Pittman-Robertson Project W-67-R. Additional support was provided by the Biology Department and Institute for Ecological Studies at the University of North Dakota. Helpful editorial comments were provided by R. -

ISPL-Insight-Aussie-Backyard-Bird-Count

Integrate Sustainability 18 October 2019 Environment Unique Birds of Australia: The Aussie Backyard Bird Count Samantha Mickan – Environmental Specialist It’s that time of year again, time for the Aussie Backyard Bird Count (Backyard Bird Count). Now in its 6th year, the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is occurring between 21st till the 27th of October and is facilitated by Birdlife Australia. Over the course the week participants are encouraged to observe birds around them for 20 minutes using the Aussie Backyard Bird Count app. What is cool is you don’t have to stay in your backyard, you can visit your local pack, nature reserve or head to the beach. Who can’t find 20 minutes, to stop and observe bird occurring in your local area? Who is BirdLife Australia? Birdlife Australia is the largest, independent, non-profit bird conservation organisation in Australia. They run the Backyard Bird Count each year to obtain valuable data on bird communities throughout Australia. The trends extrapolated from this data can be used to get a glimpse into the changes bird populations are undergoing, and subsequently the environment, as Australia’s Unique changes in populations are a reflection of changes in the environment. The count is Birds held in October each year to capture migratory birds which are returning to Australia from the northern hemisphere for nesting, breeding and flocking. Many of these migratory birds are water birds that flock to our coasts where most human populations are situated, making it an ideal time of year for counts. Backyard Bird Count Results 2018 In 2018, 76,918 people in Australia counted 2,751,113 birds over the 7-days period. -

ILLINOIS BIRDS: Hirundinidae

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Y\o. GG - €)3 SURVEY ILLINOIS BIRDS: Hirundinidae RICHARD R. GRABER J^' JEAN W. GRABER ETHELYN L. KIRK ^^^ Biological Notes No. 80 ILLINOIS NATURAL HISTORY SURVEY Urbana, Illinois — August, 1972 State of Illinois Department of Registration and Education NATURAL HISTORY SURVEY DIVISION 1969 -1967 Fig. 1.—Routes travelled in summer (1957-1970) to study breed- ing distribution of the birds of Illinois. The encircled areas were spe- cial study areas where daily censuses of migrants and nesting popula- tions of birds were carried out, 1967-1970. , ILLINOIS BIRDS: Hirundinidae Richard R. Graber, Jean W. Graber, and Ethelyn L. Kirk THIS REPORT, the third in a series of pa- particularly interesting group for distribution studies, pers on the birds of Illinois, deals with the and to determine their population trends we should swallows. The introductions to the first two papers, know the location of every major colony or popula- on the mimids and thrushes (Graber et al. 1970, tion in the state. We therefore appeal to all students 1971) also serve as a general introduction to the of Illinois birds to examine the maps showing breed- series, and the procedures and policies outlined in ing distributions, and publish any additional infor- those papers also apply to this one. mation they may have. By this procedure we will One point that warrants emphasis and clarifica- ultimately learn the true distribution of all the Illi- tion is the geographic scope of the papers. Unless nois species. otherwise indicated, the data presented and the In bringing together the available information statements made refer to the state of Illinois (Fig. -

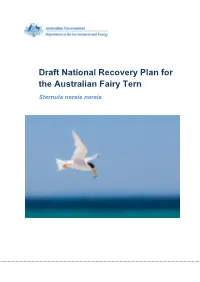

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

Breeding Biology of Asian House Martin Delichon Dasypus in a High-Elevation Area

FORKTAIL 28 (2012): 62–66 Breeding biology of Asian House Martin Delichon dasypus in a high-elevation area ZHIXIN ZHOU, YUE SUN, LU DONG, CANWEI XIA, HUW LLOYD & YANYUN ZHANG We present data on the breeding biology of the largest known colony of Asian House Martin Delichon dasypus, located in the Jiangxi Wuyishan Nature Reserve at 2,158 m in the Huanggang Mountains, China. Nest surveys conducted in abandoned buildings in a subalpine meadow during March–August 2007 and 2008 yielded 163 and 132 clutches, from 84 and 82 nests, respectively. Breeding pairs also laid multiple broods and replacement clutches. Average clutch size was 3.0 and 2.6 eggs for first and second broods respectively. Synchronous hatching was detected in 79% of clutches. The proportion of eggs hatching was 0.7 and 0.6 for first and second broods respectively, and the proportion fledging was 0.5 and 0.4 respectively. Nests situated inside buildings were more successful than those situated outside owing to greater protection from severe weather, which was the major cause of breeding failure. Nest losses caused by severe weather were more pronounced later in the breeding season. INTRODUCTION Nest surveys The 3-ha study area is predominately subalpine meadow habitat in Many bird species raise only one brood per year because of a narrow which are situated more than 30 abandoned buildings and garages period of suitable environmental conditions which prohibits that provide suitable nesting substrate for the breeding martins. The multiple breeding attempts (Evans-Ogden & Stutchbury 1996). nest of Asian House Martin is a closed cup typical of hirundines, Others raise multiple broods per breeding season (Verhulst et al.