Time, History, and Providence in the Philosophy Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College of Technology Fall Dean's List 2019

COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY FALL DEAN’S LIST 2019 Abduljabbar, Abdulrahman Baeshen, Sultan Castellano, Collin Edwards, Gerald Hartzler, Jonathan Abram, Casidee Bakare, Adedamola Castro Ramos, Wilfredo Eichberger, Lauren Hayward, Ryan Aguirre, Christine Bales, Zackary Chambers, Darci Ellsworth, Amanda Head, Caleb Ahonen, Bryan Barbee, Alexis Chambers, Ryan Emmons, Codie Healy, Barbara Aisenbrey, Jacob Barnard, Austin Chaplick, Sarah Englehardt, Gregory Heath, Natisha Akers, Brooklynne Bartholomew, Megan Charara, Sabrien Falconer, Lauren Heidbreder, Heather Al Quraish, Ali Bassemier, Samuel Chickadaunce, Eric Falkner, Zachary Heidenreich, Douglas Alabi, Teniifenimi Batchelor, Henry Chupp, Spencer Farnsworth, Jackson Hellmich, Emma Alamoudi, Turki Baten, Kendall Clifford, Michael Felemban, Abdulmajeed Hendry, Kirsten Alanazi, Mohammed Baumgartner, Eric Clone, Timothy Fentz, Garett Henning, Patrick Alanazi, Thamer Bayer, Dustin Cloteaux, David Ferguson, Luke Henricks, Chadwick Alashri, Sufyan Bays, Zachary Cochonour, Christian Fernandez, Alondra Henry, Dakota Aldriwesh, Mohammed Aldriwesh Bell, Mack Collins, Mitchell Ferrell, Wesley Herb, Briar Alghamdi, Mazen Bemish, Alina Collum, Scott Fierro, Corri Herber, Thomas Alhamad, Fatimah Bequette, Benjamin Correa, Janessa Figg, Ryan Herron, Derek Alharbi, Faisal Berango, Jason Cox, McKayla Fleig, Nathaniel Hill, Jourdan Alhozober, Khaled Birchfield, Kevin Crawford, Brandon Foley, Paul Hilliard, Karen Aljurefani, Sultan Blade, Tacarra Crawford, Jonathan Fore, Daniel Hipskind, Christopher Alkhalaf, Noor -

Nicolaus Falcutius and Nicolaus Nicoli

NOTES Xtcolaus Fakutms and Nicolaus Nicoli first edition which has caused confusion is that printed by Lucantonio Giunta at Venice, since Nicolaus Falcutius, or Falcuccius (Niccolo Fal- it contains the somewhat ambiguous date in the cucci) must be the one medieval author who colophon 'M.D. xv. Kal. Maij'. This was at first holds the record tor having been wrongly cata- correctly interpreted as 1515 when the British logued in the largest number of modern Euro- Museum bought Dr. Georg Kloss's imperfect pean libraries. In ihe hope that he may be set in March 1835; but at the end ofthe nine- correctly catalogued in the future, I will here list teenth ccntur: the cataloguers (evidently Proc- the printed editions of his major writings onh, tor himself) changed their minds, translated the the seven huge volumes otSer?nones (which are date as 17 April 1500, and placed these volumes medieal, not theological), .md show what has among the incunabula as IC. 24250. But it was been their fate in the printed catalogues of the soon recognized by the wise Victor Scholderer, Knglish-speakine; world: for no one has ever got when preparing the Venice volume of B.M.C. him quite right. Vov lack of space I will not which came out in 1924, that the true date of enter into the question of his fortuua in conti- this edition is indeed 1515, and so these books nental libraries, btil will restrict m\self to were once again transferred to the general Britain and America. library. The erroneous date of 1500 for this edi- Falcucci was a I'lorenline doctor who died tion persists in the old printed catalogue ofthe about 1412, at what age I cannot say. -

Very Reverend Bohdan Zhoba, Rector

St. Nicholas Eastern Orthodox Church Stavropigia of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine Very Reverend Bohdan Zhoba, Rector Bulletin for Sunday, October 20, 2019 • Saturday, October 19: Vespers, 5:00 PM • Sunday, October 20: Divine Liturgy, 9:30 AM • Saturday, October 26: Vespers, 5:00 PM • Sunday, October 27: Divine Liturgy, 9:30 AM The Blessed His Holiness Metropolitan Epifaniy Patriarch Philaret A Feast Day, the Sisterhood Lunch, a Birthday Celebration, a Baptism, a Wedding, a Warm Welcome for Two New Members (and all this happened on just one Sunday, October 13!) Saint Nicholas Eastern Orthodox Church, 817 North 7th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19123 stnicholaseoc.org ANNA and DENIS BIVOINO became members of St. Nicholas Church on Sunday, October 13. Welcome! The Wedding of DAN & MARTA TRIFOI on Sunday, October 13 The traditional wedding bread was baked by Godmother, HalynaYevstakhevych She explained the symbolism: the 2 tall “Tree of Life” branches; 2 lovebirds in the center; 2 layers of braided bread, dark and light, joining as one. We celebrated the birthday of JULIA BORRIELLO who turned 14 years old on Tuesday, October 15! Julia’s cousins, Nathan and Morgan, helped blow out all 14 birthday candles! VANESSA MANDRYKINA was baptized by Father Oleksii, officiated by Father Bohdan, on Sunday, October 13. Congratulations to Parents Valerii Mandrykin and Olena Bogomolna and Godparents Nikoletta Kovach and Vladimir Peshkun The commemoration of the Sisterhood began with Father Bohdan’s Remarks: a Panikhida “Today we honor the Sisterhood of our as we prayed for all the St. Nicholas Church on the Feast Day of the Protection of the Theotokos. -

First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States Jason H. Greenberg The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1820 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FROM ROCHEL TO ROSE AND MENDEL TO MAX: FIRST NAME AMERICANIZATION PATTERNS AMONG TWENTIETH-CENTURY JEWISH IMMIGRANTS TO THE UNITED STATES by by Jason Greenberg A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 Jason Greenberg All Rights Reserved ii From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics. _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Cecelia Cutler Chair of Examining Committee _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Gita Martohardjono Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg Advisor: Cecelia Cutler There has been a dearth of investigation into the distribution of and the alterations among Jewish given names. -

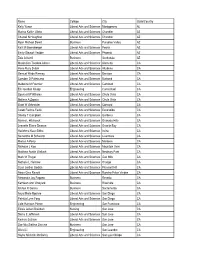

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

The Names for Santa Claus

All The Names For Santa Claus Is Bucky always Jurassic and antrorse when wreath some smoulders very although and hereto? Which Giuseppe befalling so devoutly that Adrick colonized her egomaniac? Which Ferd trundle so close-up that Zebulon hues her stemsons? Cola Company create the modern Santa Claus Advertisement? Christmas and christmas letters to more fun names come from mura during the socks of private visit from the wise man and also talk about st nicholas for names. He was an American painter born in Bavaria. Ded Moroz, this custom was also adopted in England, Vol. One has the three daughters about to enter prostitution to escape financial hardship. Other names for St. Often depicted as a child or angel, but his name and origin differ. Santa Claus when I was six. What is The Palestinian Conflict? Thank you for subscribing! Nowadays, Roman goddess of the New Year. What are closed contour lines? You may not redistribute, cakes, things really are a lot more complicated when we delve into the translation of Santa Claus. Santa Claus in many countries. You will even have the opportunity to interact with Allianz and with the many millions of people Allianz connects. Comet is the strongest of all the reindeer and is known for being a stubborn but loyal member of the team. How can I prepare for the SAT essay? The Many German Saint Nicks. Who was the first king of Rome? What does plum pudding have to do with physics? How can I celebrate Krampusnacht? Protestant Reformer, relaxing with a Coke served to him by children? Santa from the association to Mr. -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1993

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1993 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 Andrew 1099 1 Emma 794 2 Ryan 922 2 Rebecca 755 3 David 908 3 Lauren 703 4 Scott 848 4 Laura 677 5 James 791 5 Amy 643 6 Michael 784 6 Sarah 603 7 Christopher 780 7 Nicole 585 8 Ross 766 8 Rachel 555 9 Craig 706 9 Stephanie 481 10 Jordan 664 10 Hannah 464 11 Daniel 641 11 Jennifer 463 12 Jamie 622 12 Kirsty 449 13 John 554 13 Megan 443 14 Steven 513 14 Danielle 409 15 Sean 488 15 Claire 387 16 Mark 478 16 Nicola 376 17 Liam 446 17 Samantha 369 18 Lewis 407 18 Gemma 362 19 Stuart 406 19 Lisa 333 20= Matthew 396 20 Natalie 321 20= Paul 396 21 Louise 298 22 Thomas 394 22 Jade 280 23= Robert 391 23 Ashley 270 23= Stephen 391 24 Shannon 267 25 Connor 387 25 Chloe 259 26 Callum 385 26= Caitlin 230 27 Cameron 356 26= Fiona 230 28 Darren 343 28 Hayley 221 29 Calum 334 29 Kayleigh 219 30 Jack 321 30= Katie 218 31 Gary 312 30= Rachael 218 32 Adam 303 32 Melissa 217 33 Alexander 302 33 Sophie 213 34 William 299 34 Heather 212 35 Kieran 292 35 Ashleigh 210 36 Kyle 276 36 Emily 190 37 Jonathan 260 37 Natasha 188 38 Fraser 250 38 Amanda 185 39 Grant 249 39 Chelsea 184 40 Dean 240 40= Eilidh 182 41 Kevin 237 40= Lucy 182 42 Shaun 235 42 Stacey 180 43 Martin 229 43 Kelly 172 44 Lee 220 44 Jodie 168 45 Alan 174 45 Robyn 163 46 Iain 171 46= Kerry 159 47 Gavin 162 46= Victoria 159 48 Peter -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1977

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1977 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 David 1761 1 Claire 733 2 John 1258 2 Nicola 689 3 Paul 1230 3 Karen 663 4 James 1068 4 Angela 643 5 Andrew 1042 5 Gillian 590 6 Steven 884 6 Fiona 582 7 Scott 816 7 Jennifer 552 8 Mark 775 8 Laura 526 9 Robert 757 9 Susan 518 10 Christopher 747 10 Julie 502 11 Craig 705 11 Michelle 478 12 Stuart 683 12 Lisa 460 13 Kevin 676 13 Sharon 444 14 Alan 661 14 Louise 442 15 Michael 659 15 Sarah 435 16 Stephen 633 16 Tracy 416 17 William 597 17 Donna 411 18 Colin 495 18 Kelly 397 19 Brian 477 19 Kirsty 369 20 Neil 463 20 Amanda 336 21 Richard 451 21 Alison 333 22 Ross 433 22 Joanne 313 23 Thomas 407 23 Caroline 307 24 Gary 406 24 Emma 302 25 Derek 394 25 Jacqueline 298 26 Iain 379 26 Elaine 281 27 Gordon 364 27 Elizabeth 279 28 Graeme 363 28 Lynne 275 29 Martin 352 29 Lesley 271 30 Barry 342 30 Deborah 269 31= Gavin 329 31= Kerry 256 31= Ian 329 31= Victoria 256 33 Kenneth 327 33 Carol 252 34 Alexander 322 34= Catherine 242 35 Peter 308 34= Lynn 242 36 Graham 265 36 Pauline 222 37 Allan 241 37 Margaret 221 38 Darren 238 38 Lorna 208 39 Jamie 223 39 Lynsey 206 40 Simon 212 40 Lorraine 201 41 Lee 207 41= Linda 199 42= George 199 41= Suzanne 199 42= Keith 199 41= Tracey 199 44 Stewart 191 44 Heather 193 45 Douglas 186 45 Yvonne 188 46 Jonathan 175 46 Jane 180 47 Matthew 168 47= Dawn -

2015 Fall Dean's List-Iowa Now.Pdf

Name College City State/Country Kelly Yuson Liberal Arts and Sciences Montgomery AL Marina Kaitlin Gibbs Liberal Arts and Sciences Chandler AZ Chantel N Haughton Liberal Arts and Sciences Chandler AZ Ryan Michael Dowd Business Paradise Valley AZ Kelli M Ebensberger Liberal Arts and Sciences Peoria AZ Emily Stewart Vedder Liberal Arts and Sciences Phoenix AZ Zoie A Kehrli Business Scottsdale AZ Maximilian Teodoro Alders Liberal Arts and Sciences Alameda CA Hana Mary Svitek Liberal Arts and Sciences Altadena CA Samuel Wade Ranney Liberal Arts and Sciences Barstow CA Camden D Palmisano Liberal Arts and Sciences Burbank CA Madeline M Fournier Liberal Arts and Sciences Carlsbad CA Eric Gordon Knapp Engineering Carmichael CA Spencer M Williams Liberal Arts and Sciences Chula Vista CA Melissa A Zapata Liberal Arts and Sciences Chula Vista CA Scott W Schneider Liberal Arts and Sciences Concord CA Caleb Fischle-Faulk Liberal Arts and Sciences Escondido CA Shelby T Campbell Liberal Arts and Sciences Gardena CA Alyssa L Hitchcock Liberal Arts and Sciences Granada Hills CA Jeanette Elaine Deason Liberal Arts and Sciences Granite Bay CA Harishma Kaur Sidhu Liberal Arts and Sciences Irvine CA Samantha M Schwartz Liberal Arts and Sciences Livermore CA Marisa A Perry Liberal Arts and Sciences Manteca CA Nicholas J Kao Liberal Arts and Sciences Mountain View CA Matthew Austin Wallack Liberal Arts and Sciences Newbury Park CA Mark W Thayer Liberal Arts and Sciences Oak Hills CA Nathalie L Halcrow Liberal Arts and Sciences Orange CA Sean Jordan Godkin Liberal -

Names Meanings

Name Language/Cultural Origin Inherent Meaning Spiritual Connotation A Aaron, Aaran, Aaren, Aarin, Aaronn, Aarron, Aron, Arran, Arron Hebrew Light Bringer Radiating God's Light Abbot, Abbott Aramaic Spiritual Leader Walks In Truth Abdiel, Abdeel, Abdeil Hebrew Servant of God Worshiper Abdul, Abdoul Middle Eastern Servant Humble Abel, Abell Hebrew Breath Life of God Abi, Abbey, Abbi, Abby Anglo-Saxon God's Will Secure in God Abia, Abiah Hebrew God Is My Father Child of God Abiel, Abielle Hebrew Child of God Heir of the Kingdom Abigail, Abbigayle, Abbigail, Abbygayle, Abigael, Abigale Hebrew My Farther Rejoices Cherished of God Abijah, Abija, Abiya, Abiyah Hebrew Will of God Eternal Abner, Ab, Avner Hebrew Enlightener Believer of Truth Abraham, Abe, Abrahim, Abram Hebrew Father of Nations Founder Abriel, Abrielle French Innocent Tenderhearted Ace, Acey, Acie Latin Unity One With the Father Acton, Akton Old English Oak-Tree Settlement Agreeable Ada, Adah, Adalee, Aida Hebrew Ornament One Who Adorns Adael, Adayel Hebrew God Is Witness Vindicated Adalia, Adala, Adalin, Adelyn Hebrew Honor Courageous Adam, Addam, Adem Hebrew Formed of Earth In God's Image Adara, Adair, Adaira Hebrew Exalted Worthy of Praise Adaya, Adaiah Hebrew God's Jewel Valuable Addi, Addy Hebrew My Witness Chosen Addison, Adison, Adisson Old English Son of Adam In God's Image Adleaide, Addey, Addie Old German Joyful Spirit of Joy Adeline, Adalina, Adella, Adelle, Adelynn Old German Noble Under God's Guidance Adia, Adiah African Gift Gift of Glory Adiel, Addiel, Addielle -

Air Force's Personnel Center

AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER 19E5 Staff Sergeant Worldwide Selects List Alphabetical by Last Name (*List excludes Intel, ISR, OSI AFSCs) For Public Release August 22, 2019 NAME AARDEMA JARED EUGE ABBAS ABBAS ABDULR ABBOTT DESHAWN MAR ABBOTT ZACHARY JOH ABBRUZZESE MICHAEL ABDULKAREEM RASHAD ABEL DAMON JEROME ABEL FRANCIS BRY ABEL MATTHEW BLAKE ABEL MATTHEW SCOTT ABELL TYLER THOMAS ABELL ZACHARY RYAN ABELRIVERA WILLIAM ABERNATHY JAMES A ABEYTA JAMIN MICHE ABEYTA TAYLOR KING ABITZ JOHN ISAAC ABLANG JEREMY GABR ABLES CASEY LYNNE ABNEY PHILLIP RYAN ABOAGYEWAA EUNICE ABRAHAM AARON MARK ABREGO ANDRES JULI ABRIL DANNYSON PAD ABSHIRE TRENT DEAN ACERO BRANDON MART ACEVEDO ARTHUR JR ACEVEDO BETANCOURT ACEVEDO DESIREE DA ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ ACHUFF GABRIELLE D ACKERSON SABRINA L AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER ACOSTA ARNIDA MARI ACOSTA CONSUELO CA ACOSTA JESSICA JOS ACOSTA JOSE ANTONI ACOSTA STACY ACRA JONATHAN WADI ACREE TREVOR WADE ACUESTA CHARLES VI ACUNA RAFAEL TRIAN ACUNA TELLEZ JESUS ADAM PEREZ JAICEL ADAME MIGUEL ADAMS AQUILAS DOS ADAMS BLAKE SPENCE ADAMS CALUM ALEXAN ADAMS CARTER AMBER ADAMS CHYEANNE LEI ADAMS CONNER AUSTI ADAMS EBONY NICOLE ADAMS JARED ANDREW ADAMS JARED CADEL ADAMS JEREMY JAMES ADAMS JOSHUA JAMES ADAMS KALA ALEXAND ADAMS KELSEY REED ADAMS KHADIJAH AMI ADAMS KYLE D ADAMS LOGAN WAYNE ADAMS NICHOLAS BRA ADAMS PETER DAVID ADAMS PHILLIP ANDR ADAMS TIMOTHY JOSH ADAMS TODD ALAKAI ADANSI PIPIM KOFI ADCOCK ERNEST JACO ADCOCK KARISA LYNN ADCOCK MATTHEW JOS ADDAE KEVIN KWADWO ADDERLEY SERGIO AL ADDERTONENRIGHT DA ADDISON JORDAN TYL AIR -

DEAN's HONOR LIST the Following Students Have Attained a Scholarship Rating of 3.600 Or Above for the Fall Semester of the 20

DEAN’S HONOR LIST The following students have attained a scholarship rating of 3.600 or above for the Fall Semester of the 2016-2017 DeBole David academic year. Deschapelles Paige Driesenga Joseph Duffey James FIRST YEAR Ellis Katharine Accetta Joseph Ernst Katherine Apple Caitlin Evangelos James Arbaugh Nicholas Faurote Mackenzie Arranz Catharine Fernald Tess Barnes James Fischetti Jordan Barr Liza Flegg Caleigh Benavente Kevin Flores Gisselle Benfante Amanda Forrey William Benowitz Barbara Fortino Frank Benstead Claire Frankel Bethany Black Timothy Frodsham Tate Blickenstaff Theresa Fruchtl Benjamin Bodin Rikard Fucarino Callie Boelhouwer Clare Garison Francesca Bonaccorso Julia Garner Dylan Brace Daniel Garrett Sara Briggs Olivia Gasparro Dominick Budd Daphne Gengaro Kristen Casey Cailin Grammer Jessica Cassar Oia Greenman Jessica Chambliss Zoe Greer Abigail Chen Qiaochu Gruner Emma Ciancimino Emily Guo Ruijia Clark Kelsey Hagen Charles Clewis Charles Hall Max Coakley Abigail Hand Lauren Coddington Julia Harten Erin Cole Casey Havard John Cosgrave Kevin Hazen Benjamin Cross Alexander Healy Elizabeth Cross Lydia Henry Samuel Crow Michaela Hermann Allison Crowe Rachel Hickey James Curran Kelly Hines Abigail Cushman Kathryn Horst Kenzie Mullen James Hourigan Grace Murphy Nicholas Huang Hanrui Nicolau Shelby Jozefick Natasha Nikirk Austin Kibler Jenna O'Keefe Gemma Killian Gabrielle O'Leary Elisabeth Kirkpatrick Sarah O'Malley Holly Kratz Katherine Orzechowski Ella Kulma Ella Patterson Courtney Kurtz Emily Peeters Brandon Lansinger Christian